An Adaptive Evolutionary Approach for Discovering Stochastic Agent-Based Models

and

a University of Auckland, New Zealand

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (4) 1

<https://www.jasss.org/28/4/1.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5737

Received: 04-Sep-2024 Accepted: 27-Jun-2025 Published: 31-Oct-2025

Abstract

This research proposes an Adaptive Genetic Programming (AGP) approach within the Inverse Generative Social Science (IGSS) framework to effectively discover stochastic behavioural rules for Agent-Based Models (ABMs). Our method explicitly incorporates stochastic decision-making alongside deterministic primitives to realistically simulate complex human behaviours, exemplified by pedestrian exit choices in crowded environments. The AGP algorithm integrates dynamic population resizing, elite-based restarts, and adaptive termination criteria, enhancing computational efficiency and robustness against local optima. Through rigorous evaluation, the AGP successfully recovered the original pseudo-truth rule—agents selecting exits based on combined distance and crowding—used to generate synthetic datasets. Notably, rules considering both crowd density and distance outperformed simpler rules relying solely on proximity. Robustness analyses demonstrated that the evolved pseudo-truth rule consistently achieved better performance compared to other evolved alternatives, while most evolved rules performed significantly better than the null comparator baseline. Sensitivity analysis further validated the algorithm's effectiveness in balancing exploration and computational cost. These results demonstrate AGP's potential for uncovering interpretable and empirically grounded behavioural rules, with broad applicability to various stochastic social simulation scenarios.Introduction

Generative social science aims to explain macroscopic social phenomena through the interactions of individual agents (Epstein 1999). Agent-Based Models (ABMs) are fundamental to this approach, allowing researchers to explore how individual-level behaviours and decisions collectively give rise to emergent system-level patterns (Borrill & Tesfatsion 2011; Clifford 2008; Smith & Conrey 2007). Typically, ABMs derive decision-making rules from expert knowledge, theoretical frameworks, and empirical data (Smith & Conrey 2007), and are carefully calibrated and validated to closely align simulation outcomes with real-world observations (Medina et al. 2021). The strength of ABMs lies in their ability to capture complex, nonlinear interactions and individual heterogeneity, revealing emergent patterns otherwise hidden when examining individual components in isolation.

Despite their strengths, ABMs struggle to capture the full complexity of human behaviour using predefined handcrafted rules, often implicitly assuming agent homogeneity (Badham et al. 2018; Schratter et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2014). Human decision-making is inherently stochastic and affected by diverse factors such as personal preferences, environmental conditions, and spontaneous actions. To overcome these limitations, researchers have introduced alternative approaches such as Pattern-Oriented Modelling (POM) and Machine Learning (ML)-based simulations. POM involves manually creating multiple candidate models to test different theoretical patterns against real-world scenarios (Grimm et al. 2005; Wilensky & Rand 2007). However, practical constraints usually lead modellers to focus on a single representative model, subjected to sensitivity analyses to address structural uncertainties. In contrast, ML methods enable broader computational exploration of ABM variants, potentially uncovering model structures unanticipated by human modellers. ML-driven approaches facilitate the inverse modelling of ABMs by inductively identifying agent rules directly from the data (Antosz et al. 2022).

Although powerful, many ML techniques such as artificial neural networks, support vector machines, and random forests act as "black boxes," offering predictive power without transparent explanations of underlying decision processes or causal mechanisms (Rand 2019; Sharma et al. 2018; Wu & Silva 2010; Zhu et al. 2023). Genetic Programming (GP), a type of evolutionary ML algorithm, addresses this transparency issue by automatically evolving human-readable behavioural rules from empirical data (Smith 2008). This approach, termed Inverse Generative Social Science (IGSS), reverses the conventional modelling direction. It starts with observed macro-level patterns and evolves micro-level agent behaviours capable of producing these outcomes, meeting the explanatory criterion known as generative sufficiency (Epstein 2023). Rather than testing predefined theories, IGSS generates multiple plausible micro-level explanations for macro-level phenomena through automated model discovery (Gunaratne & Garibay 2017; Vu et al. 2019).

However, existing inverse generative social science (IGSS) methodologies have generally evolved agent decision rules using deterministic structures (Gunaratne & Garibay 2017, 2020), where stochasticity is introduced primarily during the simulation phase via probabilistic sampling, as demonstrated by (Vu et al. 2019, 2020, 2023). Although their rules produce stochastic outcomes, the decision structures themselves do not explicitly embed stochastic primitives. Recent work by Miranda et al. (2023) advanced IGSS by explicitly incorporating stochastic primitives within the evolved agent rules, directly embedding randomness into the rule structures. Nevertheless, there remains a notable gap: Miranda et al. (2023)’s approach explores stochasticity mainly through probabilistic numeric expressions rather than through structural decision-making logic.

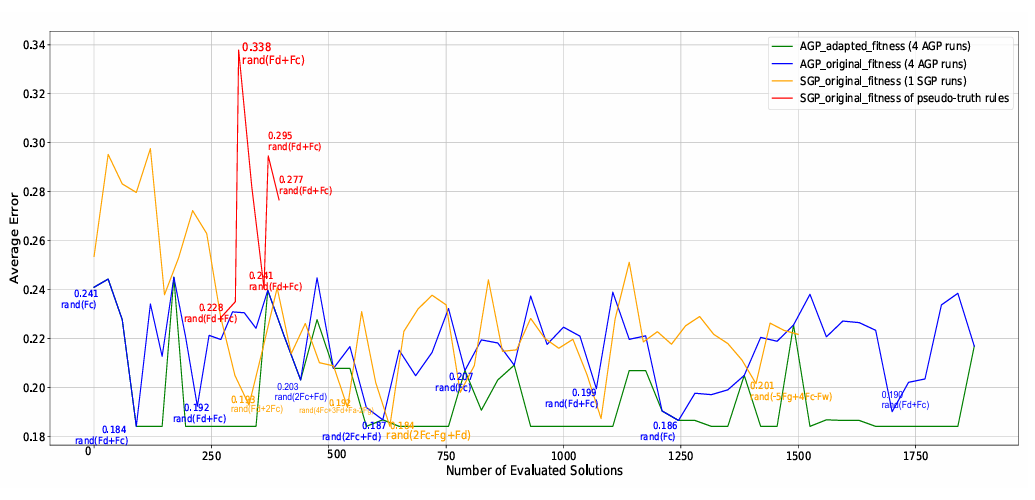

To bridge this gap, the current study extends the IGSS framework by explicitly combining deterministic decision primitives (minimum and maximum comparators) and stochastic selection primitives (random selection comparators) directly within the agent rule evolution process. This approach enables a more comprehensive and realistic representation of human behavioural variability. However, evaluating structurally stochastic rules requires extensive simulations and repeated sampling, introducing risks such as fitness noise and premature convergence to local optima. In preliminary experiments, traditional GP with a fixed population often failed to consistently identify the pseudo-truth rule used to generate synthetic data. In one illustrative run, although the pseudo-truth rule emerged early in the search process, it was later discarded in favour of overfitted alternatives exploiting randomly initialised features such as gender. These limitations motivated our Adaptive GP (AGP) approach, which uses dynamic fitness re-evaluation and elite preservation mechanisms. A comparison of AGP and traditional GP results is provided in Appendix B.

To address these challenges, this study introduces an Adaptive Genetic Programming (AGP) methodology which includes:

- Dynamically adjusts population size to explore many regions in the search space at the begining and later exploit solutions within known promising areas,

- Dynamically adjusts generation count to overcome local optima and move to next run quickly,

- Multiple restarts with elite populations to enhance solution quality and computational efficiency, and

- Tracking the best fitness values (minimum average error) for unique individual for guided fitness update to overcome overfitting while addressing the issue higher variability stochastic candidate rules.

Through these innovations, this research advances the IGSS framework, facilitating the discovery of empirically grounded, behaviourally realistic agent mechanisms. To illustrate our approach’s practical utility, we apply it to pedestrian behaviour modelling using StationSim, an established ABM simulating pedestrian movements within train stations. This case study offers an ideal context due to the inherent simplicity yet stochastic complexity of pedestrian behaviours in crowded environments.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides essential background information. Section 3 details the methodology of our model discovery process, emphasising evolutionary computation techniques. The results of applying our approach to pedestrian modelling are presented in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 discusses the implications of our findings and outlines avenues for future research.

Related Works

Inverse Generative Social Science

Evolutionary algorithms have been increasingly utilised to automate scientific discovery across various disciplines. Techniques such as Genetic Programming (GP) leverage evolutionary principles to optimise equations, simulations, or programmes based on defined fitness objectives (Krawiec & Liskowski 2015; Wehrens & Buydens 1998). Early work by Joyce et al. (2012) showed how binary state update rules could evolve using GP, enabling localised interactions in agent-based models (ABMs) to produce emergent network intelligence akin to brain dynamics. This vision of automated discovery has since been extended into social sciences through Inverse Generative Social Science (IGSS), which applies evolutionary computation to automatically generate ABMs capable of explaining macro-level social phenomena from observed data (Epstein 2023).

IGSS aims to reduce the reliance on predefined assumptions and expert knowledge, potentially discovering parsimonious, yet insightful, explanations of social patterns (Greig et al. 2023; Gunaratne et al. 2021). It prioritises a balance between empirical accuracy and theoretical interpretability, aiming for models that not only fit data, but also provide meaningful explanations (Vu et al. 2023).

Prior IGSS research has explored domains such as residential segregation, alcohol consumption, flocking behaviours, and irrigation dilemmas. Gunaratne & Garibay (2017), Gunaratne et al. (2021), Gunaratne & Garibay (2020), Gunaratne et al. (2023) introduced Evolutionary Model Discovery (EMD), employing GP to discover agent decision rules for residential segregation, expressed as mathematical equations combining behavioural factors such as racial bias and isolation. Similarly, Miranda et al. (2023) used EMD to discover decision rules for cooperative irrigation behaviours, evaluating their accuracy against experimental data. The author examined stochastic and social factors in irrigation infrastructure maintenance.

Another significant advancement has been the integration of multi-objective evolutionary computation into IGSS, notably by Vu et al. (2019), Vu et al. (2020), Vu et al. (2021), Vu et al. (2023). Their Multi-Objective Grammar-based Genetic Programming (MOGGP) approach explores combinations of theoretical constructs to model alcohol consumption trends, addressing trade-offs between model complexity, empirical fit, and theoretical coherence. Further studies illustrate the versatility of IGSS: Chesney et al. (2024) evolved agent rules for conflict scenarios; Greig et al. (2023) created flexible ABMs for flocking and opinion dynamics.

Despite these advancements, IGSS faces notable challenges. Most existing methodologies have primarily used various rule representations ranging from deterministic formulations (Gunaratne et al. 2023; Gunaratne & Garibay 2020) to probabilistic structures. Notably, Vu et al. (2019), Vu et al. (2020), Vu et al. (2021), and Vu et al. (2023) modelled the disposition to drink in an alcohol use simulation as a stochastic process, where the rule produces probabilities rather than fixed decisions. This incoorporates stochasticity indirectly through probabilistic sampling rather than within the rule structures themselves (Miranda et al. 2023; Vu et al. 2023). Computational complexity and issues such as local optima, sensitivity to initial conditions, and overfitting remain significant hurdles (Greig et al. 2023). Moreover, the interpretability of evolved rules can diminish due to complex or bloated structures, despite efforts to constrain complexity (Gunaratne et al. 2023; Vu et al. 2023). Therefore, integrating stochastic elements explicitly into rule structures emerges as a critical area for further research.

Stochastic elements in social modelling

Human behaviour, especially decision-making and movement, inherently involves uncertainty and multiple plausible outcomes, challenging precise prediction (Xu et al. 2022). Pedestrian behaviour particularly exemplifies this complexity, as their decisions depend on dynamic social interactions, environmental cues, and individual preferences (Gu et al. 2022). Consequently, probabilistic modelling approaches, such as fully Markovian approaches (Papadimitriou et al. 2009), variational autoencoders and diffusion models, are increasingly utilised to represent this stochastic nature by generating probability distributions rather than single deterministic predictions (Fard et al. 2022).

Recent empirical research highlights the value of explicitly probabilistic rules for modelling stochastic human decisions, yet IGSS approaches often focus on deterministic rule structures that indirectly simulate stochastic outcomes (Miranda et al. 2023; Vu et al. 2023). A notable limitation is that these approaches typically employ deterministic selection operators (e.g., argmax, argmin), thereby constraining the representation of genuine behavioural uncertainty. Addressing this gap, explicitly incorporating stochastic primitives within evolutionary processes would allow more realistic modelling of inherently uncertain human behaviours. A potential enhancement to the IGSS methodologies could involve introducing a “random_select" operator into the primitive set for the evolution of truly stochastic agent behaviours, such as”IF condition THEN random_select(probabilities)". This enables models to generate distributions of possible behaviours rather than single deterministic predictions. While this would increase computational complexity and other limitations in discovering stochastic ABMs highlights a significant area for future research in the field of IGSS.

Adaptive algorithms in evolutionary computation

Adaptive Genetic Programming (AGP) methods dynamically adjust algorithm parameters such as mutation rates, crossover probabilities, and population sizes during optimisation, enhancing search efficiency and avoiding premature convergence (Eiben et al. 1999; Hinterding et al. 1997; Koza 1992). Unlike traditional static parameter approaches, adaptive techniques balance exploration (broad search) and exploitation (focused refinement), potentially avoiding premature convergence, reducing manual tuning requirements and improving convergence reliability across diverse problem spaces (De Jong 2007; Eiben & Schippers 1998; Liang & Leung 2011).

Several adaptive GA approaches have been successfully applied to complex real-world problems. Examples include adaptive restarts to avoid local optima (Dao et al. 2015), dynamic population management (Zachariah et al. 2023), fuzzy logic-based operator adjustments (Muzid 2020), and hybrid algorithms combining GA and machine learning (Mao et al. 2021). Zachariah et al. (2023) proposed a modified GA called Multiple Restart Dynamic Population Genetic Algorithm (MRDPGA) to adaptively modify the population size and multiple restarts with elite individuals, in an attempt to avoid getting trapped in local optima and find better global solutions.

Adaptive algorithms also show promise in handling stochastic environments, adjusting parameters to maintain performance amidst noisy fitness evaluations and uncertain conditions (Mao et al. 2021; Qi 2018; Zhou & Cai 2014). Thus, integrating adaptive methodologies within IGSS could significantly enhance algorithmic efficiency, particularly in stochastic settings.

Contribution

Existing IGSS methodologies have primarily explored deterministic rules or indirectly introduced stochasticity through numeric probabilistic primitives (Gunaratne et al. 2023; Miranda et al. 2023; Vu et al. 2023). In contrast, this research explicitly incorporates structural stochasticity by introducing random comparator primitives directly within the evolutionary process. This method allows agents to select behaviours stochastically based on calculated probabilities from multiple decision factors, more accurately capturing the inherent uncertainty in human decision-making. This caters for uncertainty in strategy selection rather than strategy execution and better explains human decisions. This approach also retains the interpretability of distinct rules while capturing unpredictability.

However, evolving such explicitly stochastic ABMs poses significant computational challenges, as robust fitness evaluation requires extensive simulation repetitions. Previous deterministic explorations typically conducted a limited number of simulations per individual to accommodate for random seed requirements. For example, Gunaratne et al. (2023) conducted five simulations of GP-evolved ABMs with slightly randomised parameters (within ±5% of optimal values) and Vu et al. (2023) simulated each GP-evolved model structure ten times with different random seeds for more robust evaluation. However, stochastic rules demand substantially more repetitions to accurately measure their performance and variability. This is evidenced by studies in stochastic parameter optimisation, where researchers have employed 30 to 50 simulation runs per GP individual in stochastic parameter optimisation problems (Ghasemi et al. 2021). This significant increase in the number of required simulation runs introduces a considerable computational burden to the model discovery process.

To cope with this computational burden, the present study employs an adaptive genetic programming framework that gives priority for stochastic rule generatio while helping resolve the GP related computation by dynamically adjusting population sizes, implementing local termination criteria, guided fitness update, and employs multiple restarts with elite individual retention. This approach aims to balance exploration (with larger populations early on) and exploitation (focusing on best solutions later) dynamically throughout the optimisation process. The population shrinks based on fitness convergence. Thus, this research contributes both methodologically, through explicit stochastic primitives and adaptive evolutionary techniques, and practically, by improving computational efficiency and realism in the discovery of stochastic ABMs.

Methodology

This section presents the human behaviour problem and proposes AGP’s stochastic rule discovery for ABMs.

Agent-based simulation: The StationSim model

The StationSim ABM serves as the ideal testbed for our study due to the inherent stochasticity in simulating crowd dynamics within a station environment (Malleson et al. 2020). In the model, N agents represent passengers navigating a rectangular platform from three entrance points to two exit locations. Unlike the original model, where exit selection was random and static, we implemented a random and dynamic exit selection process, which is the focus of our rule discovery. Agents are characterised by heterogeneous attributes that include age, gender, and maximum speed, sampled from appropriate distributions. These characteristics influence agent behaviour and decision-making throughout the simulation.

As agents traverse the platform, they employ basic movement rules and collision avoidance techniques. When encountering slower agents, they perform "wiggle" manoeuvres, attempting to overtake by moving left or right. This local interaction mechanism gives rise to emergent macro-level congestion patterns, which vary across simulation runs. The entrance and exit points have defined widths, which impose realistic capacity constraints on agent flow.

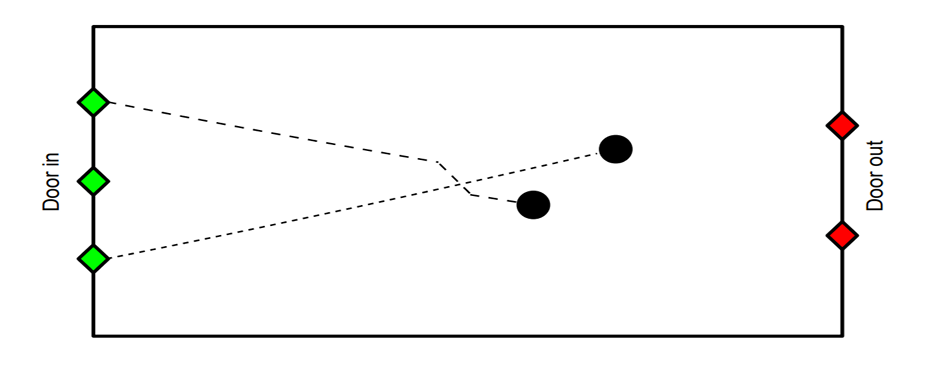

The model emphasises three key features: (1) individual heterogeneity, reflected diverse attributes and maximum speeds; (2) agent interactions, manifested through spatial constraints and overtaking behaviours; and (3) emergent phenomena, particularly in the form of crowd dynamics and exit utilisation patterns. The simulation terminates when all agents have successfully exited the platform. Figure 1 illustrates the StationSim environment, showing the configuration of the platform with three entrances and two exits, along with the trajectories of the sample agents.

This enhanced StationSim model serves dual purposes in our research: it generates a syntheric using a predefined exit selection rule and acts as the evaluation environment for testing evolved rules within our model discovery process. Using the same model for both data generation and evaluation, we ensure consistency and isolate the impact of the exit selection rule, allowing for a focused examination of the evolutionary model discovery approach.

A complete formal description of the StationSim ABM following the ODD (Overview, Design concepts, and Details) protocol is provided in Appendix A.

Rule/model discovery process in Adaptive Genetic Programming (AGP)

Model discovery in IGSS involves the automated exploration of a vast space of potential agent rules or model structures to identify those that best reproduce observed social phenomena. The process emphasises not only empirical accuracy but also generative power, theoretical interpretability, and minimal prior assumptions (Epstein 2023; Greig et al. 2023; Gunaratne et al. 2023; Miranda et al. 2023; Vu et al. 2023).

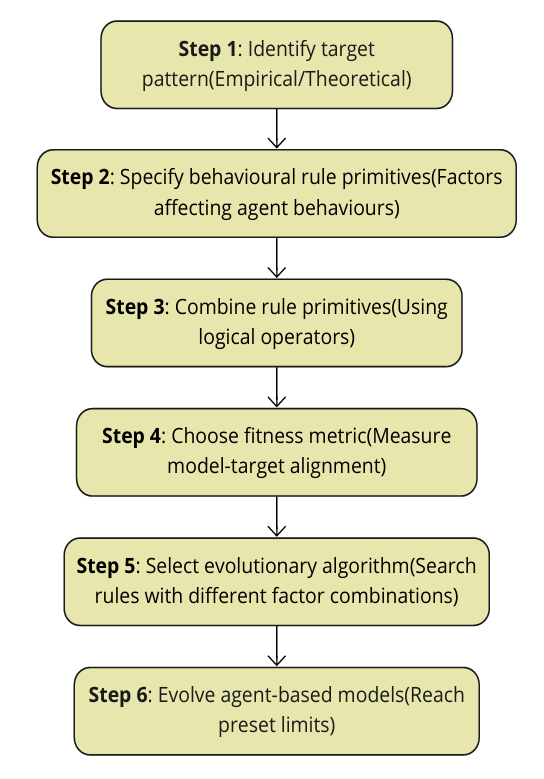

This study follows the six-step IGSS framework proposed by Epstein (2023), which is summarised in Figure 2, to guide the discovery of stochastic agent rules using AGP. The framework begins with the identification of a macroscopic target pattern, which the evolving agent-based models (ABMs) aim to replicate. This target provides a concrete objective for the evolutionary search, ensuring that model development is focused on replicating meaningful system-level behaviours. The second and third steps involve specifying the set of behavioural primitives and defining how these primitives can be combined through logical or mathematical operators to construct more complex decision rules. A fitness function (Step 4) is defined to quantitatively measure the degree of alignment between the model outputs and the target pattern. In Step 5, an evolutionary algorithm is selected to perform the search, employing genetic operations such as crossover, mutation, and selection to iteratively refine candidate rules based on fitness. Finally, Step 6 specifies the stopping criteria, such as a convergence threshold, maximum number of generations, or computational budget limit, ensuring that the evolutionary process terminates appropriately.

The rest of this section explains each step in implementating AGP according to the Epstein (2023) framework.

Step 1: Macroscopic target pattern

AGP framework seeks to generate stochastic exit selection behaviours from the bottom-up, guided by a macroscopic target pattern. In this study, the StationSim ABM provides a controlled environment where the ground-truth exit behaviours are known, enabling a robust evaluation of the rule discovery process. Unlike real-world scenarios, where the underlying decision mechanisms are often obscured, the use of simulated data allows rigorous benchmarking of how well evolved rules reproduce known patterns (Sandve & Greiff 2022).

To construct the synthetic target dataset to evaluate the IGSS-discovered rules, a pseudo-truth decision rule was designed. This rule probabilistically combines two key environmental factors, the distance to exits and crowding levels near exits, both of which are recognised as critical influences on exit selection (Wang et al. 2020). Rather than employing a simple heuristic, the pseudo-truth rule assigns selection probabilities inversely proportional to distance and crowd density, generating plausible but non-deterministic agent behaviour. The exact mathematical formulation is described in the Exit Selection Submodel of the ODD protocol (Appendix A). This design introduces structural stochasticity into the model and serves as the benchmark to evaluate the fidelity of the evolved stochastic rules.

The study considers two types of macroscopic patterns as our target outputs:

- Cumulative Exit Flow: Aggregated number of agents exiting through each exit over time, capturing long-term evacuation dynamics.

- Exit Flow Rate: The number of agents that exit at each time step, capturing short-term congestion and burst patterns.

These two outputs capture not only the cumulative evacuation behaviour, but also the dynamic fluctuations in exit flow, allowing us to evaluate whether the evolved rules can replicate both steady-state and transient crowd dynamics. The synthetic dataset records the mean count and standard deviation for these two output types over 100 simulation runs (initialised for different radomseeds).

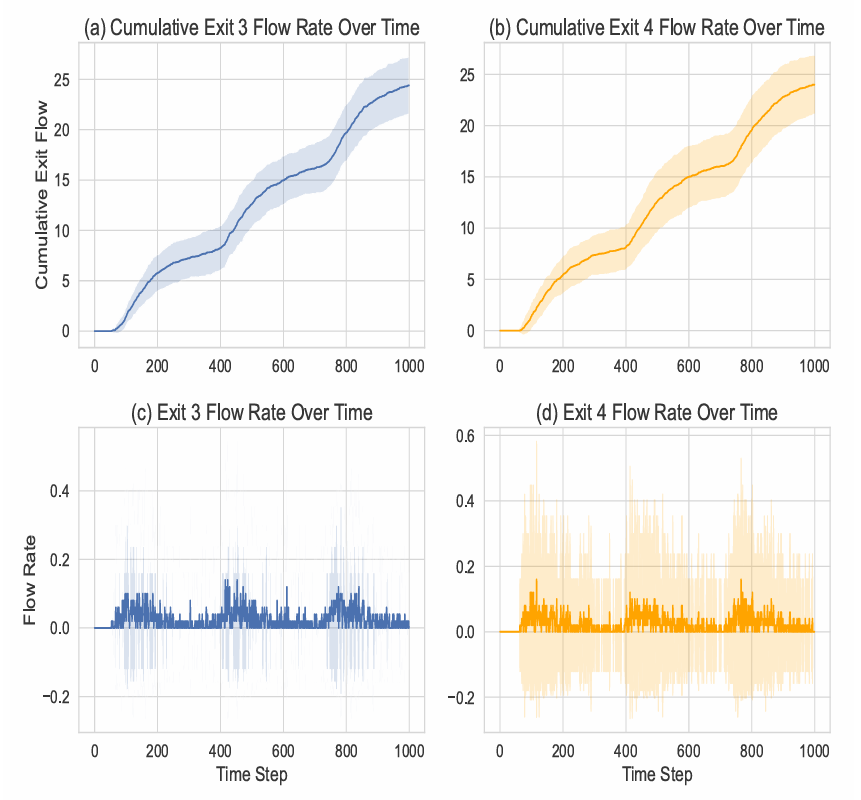

The macro-level target patterns are visualised in Figure 3. Panels (a) and (b) show the cumulative flow rates for Exit 3 and Exit 4, respectively, while panels (c) and (d) present the corresponding instantaneous flow rates.

The cumulative flow plots (Figures 3(a) and (b)) reveal gradual accumulation patterns punctuated by periods of increased activity, corresponding to simulated train arrivals. The flow rate plots (Figures 3(c) and (d)) exhibit clear temporal dynamics, with peaks and valleys indicating bursts of crowd movement influenced by congestion and stochastic decision-making. Notably, the standard deviation bands illustrate the underlying variability introduced by stochastic elements in the model, highlighting the necessity for evolved rules to capture both mean behaviours and their fluctuations over time.

Step 2 and 3: Alternate hypothesised factors and logical operators that influence the exit selection decision

The hypothesised factors for exit selection in the refined StationSim model draw inspiration from Epstein’s Agent_Zero framework, which posits that agent behaviour arises through the interplay of rational, social and emotional dimensions (Epstein 2023). Our model incorporates these three dimensions through a set of primitives, as outlined in Table 1.

| Node / Factor | Mathematical / Logical Expression or Description | Return Type | |

| Exit Selection Operators | |||

MinOf |

\(\min\limits_{i \in \text{exits}} \left( \text{comparator}_i \right)\) | exit | |

MaxOf |

\(\max\limits_{i \in \text{exits}} \left( \text{comparator}_i \right)\) | exit | |

RandomOf |

\(\text{random_select}_{i \in \text{exits}} \left( \text{comparator}_i \right)\) | exit | |

+ |

\(\text{comparator}_1 + \text{comparator}_2\) | comparator | |

- |

\(\text{comparator}_1 - \text{comparator}_2\) | comparator | |

PotentialExits |

Set of available exits | exits | |

| Rational Factors | |||

CompareDistance (Fd) |

\(P_i = \frac{\frac{1}{d_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^{n} \frac{1}{d_j}}\) | comparator | |

CompareWidth (Fw) |

\(P_i = \frac{w_i}{\sum_{j=1}^{n} w_j}\) | comparator | |

| Social Factors | |||

CompareCrowd (Fc) |

\(P_i = \frac{\frac{1}{c_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^{n} \frac{1}{c_j}}\) | comparator | |

CompareGender (Fg) |

\(P_i = \frac{g_i}{\sum_{j=1}^{n} g_j}\) | comparator | |

| Emotional/Social Factors | |||

CompareAge (Fa) |

\(s_i = 1 - \left| \frac{a - \bar{a}_i}{a_{\text{max}}} \right|,\quad P_i = \frac{s_i}{\sum_{j=1}^{n} s_j}\) | comparator | |

Variable Definitions:

- \(P_i\): Normalized probability for selecting exit \(i\)

- \(d_i\): Distance to exit \(i\), \(w_i\): Width of exit \(i\), \(c_i\): Number of nearby agents at exit \(i\)

- \(a\): Agent’s age, \(\bar{a}_i\): Average age near exit \(i\), \(a_{\text{max}}\): Max age in simulation

- \(g_i\): Count of same-gender agents near exit \(i\)

- \(s_i\): Age similarity score, \(n\): Total number of exits

The rational dimension encompasses factors that agents are likely to consider based on observable environmental characteristics. Specifically, the primitive CompareDistance (\(F_d\)) captures the inverse relationship between distance and exit preference, favouring nearer exits. Similarly, the primitive CompareWidth (\(F_w\)) models an agent’s preference for wider exits, under the assumption that wider exits facilitate easier and faster passage. Together, these primitives correspond to the cognitive decision-making layer in Agent_Zero.

The social dimension accounts for how agents are influenced by their social environment. The primitive CompareCrowd (\(F_c\)) discourages agents from selecting congested exits by inversely weighting exits according to the number of agents nearby. The primitive CompareGender (\(F_g\)) models a social preference for proximity to agents of the same gender, capturing subtle social affiliation tendencies. These factors reflect social contagion and peer influence mechanisms that shape movement behaviours in crowd contexts.

The emotional/social dimension is represented through the primitive CompareAge (\(F_a\)), which captures the emotional comfort of agents by favouring exits near peers of similar age. This mechanism aligns with the affective component of Agent_Zero, where identity and emotional factors modulate rational decision-making. Previous research has demonstrated the role of age similarity in evacuation dynamics, particularly in influencing anxiety regulation and group cohesion (Kinateder et al. 2015).

Each comparator primitive returns a normalised probability distribution over the available exits, enabling flexible and probabilistic decision-making. These probabilities can be combined using arithmetic operators (+, -) and the final exit selections are made through logical operators such as MinOf, MaxOf, and RandomOf. For instance, a composite rule \(R(x)\) may be formulated as:

| \[R(x) = F_{d} + F_{c} - F_{a}\] | \[(1)\] |

The agents then determine their selected exit \(e^{'}\) by applying an appropriate decision criterion—such as argmax, argmin, or random selection—over the computed \(R(x)\) values:

| \[e^{'} = argmin R(x)\] | \[(2)\] |

The rule structures are encoded as tree-based genetic programming (GP) individuals, with terminals representing behavioural primitives and non-terminals representing combinatory operators. The evolved decision trees are subsequently translated into modular Python functions, allowing seamless integration with the StationSim model for fitness evaluation and evolutionary optimisation.

Step 4: Fitness metric

The fitness function is designed to quantitatively assess how closely the candidate exit selection rules reproduce the pseudo-truth macroscopic patterns. For each candidate rule, 15 independent simulations are performed to account for stochastic variability in the model output. The simulation environment is implemented through the StationSim ABM, where each evolved rule governs the agent’s exit decision process.

The fitness evaluation considers two key outputs: (1) the instantaneous flow rate at each exit over time, and (2) the cumulative number of agents exiting through each exit over time. Both the mean and standard deviation across the 20 simulation runs are computed for these outputs to capture not only the average system dynamics, but also the variability due to stochastic influences. For each output type, the fitness function computes the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) between the simulated statistics and the corresponding synthetic dataset.

The per-exit, per-timestep mean and standard deviations for flow rate or cumilative flow are first calculated as:

| \[X_{i,t} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} x_{i,t,j}\] | \[(3)\] |

| \[Y_{i,t} = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{j=1}^{n} (x_{i,t,j} - X_{i,t})^2 }\] | \[(4)\] |

The error components are then computed using the RMSE between the simulated statistics and their pseudo-truth counterparts (\(X'\), \(Y'\)):

| \[Error_{j} = \sum_{i} \sum_{t} \sqrt{(X_{i,t} - X'{i,t})^2 + (Y{i,t} - Y'_{i,t})^2}\] | \[(5)\] |

Finally, the overall fitness score for a candidate rule is computed as,

| \[Original_{fitness} =0.5*Error_{flow rate} + 0.5* Error_{cumulative flow}\] | \[(6)\] |

This composite score balances accuracy across both output types.

While the use of multiple simulation runs mitigates the variability introduced by random seeds, certain rules such as those involving probabilistic exit selection, exhibit inherently higher stochasticity. To ensure fair evaluation and stable selection pressure, an adaptive fitness mechanism is employed.

Each unique rule (represented by its syntactic string) is tracked throughout the evolutionary run. If the same rule is evaluated multiple times, its lowest observed fitness score is retained and reused in subsequent comparisons. Specifically, if a rule is re-evaluated and yields a worse fitness due to stochastic effects, its previously achieved best fitness is preserved and assigned. This adaptive strategy ensures that candidate rules are not penalised for momentary fluctuations in performance, particularly when their behaviour is non-deterministic by design.

By combining multi-run evaluation, error aggregation over both flow rate and cumulative flow outputs, and adaptive fitness preservation, the evaluation process robustly selects rules that accurately reproduce both average evacuation dynamics and their variability over time.

Step 5 and 6: Adaptive genetic programming and grammatical evolution with preset limits

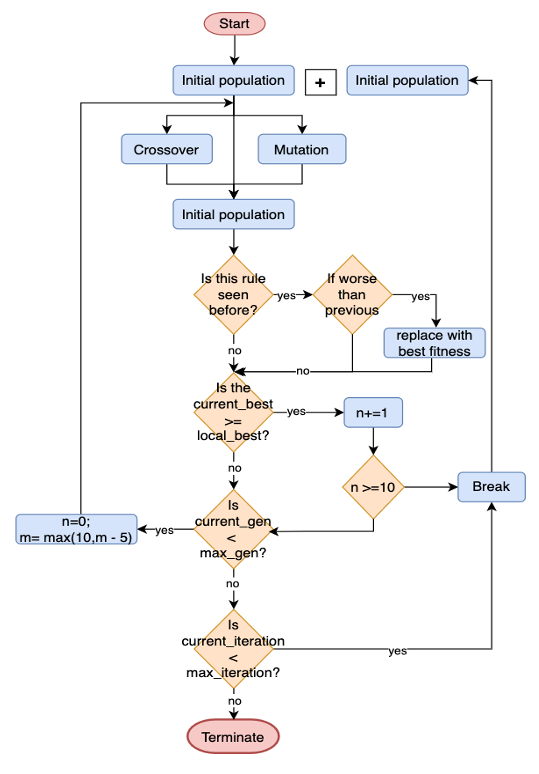

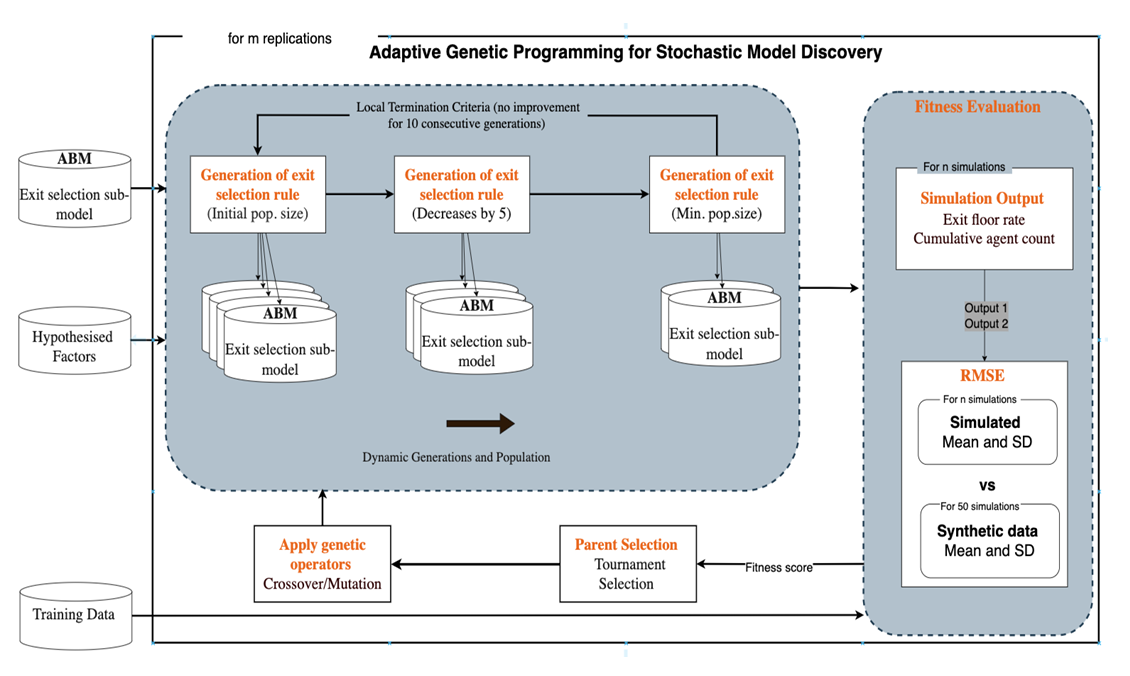

The AGP approach proposed in this study is specifically designed to efficiently discover optimal stochastic exit selection rules in highly variable environments. It incorporates several dynamic features: adaptive population size, local termination criteria, multiple reruns with elite retention, and guided fitness updates, to balance exploration and exploitation throughout the evolutionary search (Figure 4). These mechanisms collectively address challenges posed by high stochasticity in model outputs, especially when random rule initialisations could otherwise dominate early evolutionary stages.

The search process begins with an initial population of candidate rules, each represented as a tree structure using strong typing constraints. These trees have a minimum depth of 2 and a maximum depth of 8, ensuring that rules are sufficiently expressive yet interpretable while preventing uncontrolled code bloating. Fitness evaluation involves embedding each rule into the ABM and running 20 simulations to compute the RMSE-based fitness metric described earlier.

Parent selection is performed using tournament selection with a tournament size of 3. Selected individuals undergo standard genetic operations: subtree crossover (with a probability of 0.8) and mutation (with a probability of 0.1). This enables both the recombination of promising rule structures and the exploration of new behavioural primitives.

To enhance search efficiency and robustness, an adaptive population control mechanism is implemented. Whenever a new best-performing individual is identified (i.e., an individual with a lower average error), the population size is reduced by five individuals, down to a minimum population of 5. This dynamic shrinkage serves two objectives:

- Computational efficiency: Fewer individuals are required once promising solution regions are identified, reducing computational resources.

- Focused search: The search increasingly focusses on exploiting the most promising rules as evolution progresses.

To prevent the algorithm from stagnating or getting trapped in sub-optimal solutions, this study implements a dynamic termination strategy. If no improvement in the best fitness score is observed over 10 consecutive generations, the current evolutionary run is terminated. Rather than terminating the search, the algorithm initiates a restart: a new population is generated while preserving the top five unique individuals from the preceding run. This elitist re-initialisation prevents premature convergence to local optima and ensures that evolutionary progress is retained across restarts.

Each evolutionary run is allowed a maximum of 50 generations; however, due to the dynamic termination condition, many runs conclude earlier. The entire stochastic model discovery process comprises up to five reruns (replications), offering multiple opportunities to escape suboptimal regions and fully explore the rule space.

This adaptive AGP framework allows the evolutionary process to transition naturally from broad exploration during the early stages, where diverse rule structures are trialled, to targeted exploitation, refining high-quality rules in later stages. Moreover, the combination of elite retention and guided fitness-based restart mechanisms effectively counters the challenges posed by stochastic noise and random poor-performing initialisations.

The overall stochastic model discovery framework is summarised in Figure 5. Starting from the generation of an initial population of Python-based StationSim ABMs (with varied exit selection submodels), candidate rules are evolved through AGP. Fitness is evaluated at each generation using the RMSE-based metric across multiple simulation runs.

In summary, the proposed model discovery framework that systematically integrates the six-step IGSS process with an AGP strategy tailored for high-stochasticity environments. By defining clear macroscopic target patterns, constructing a theoretically grounded primitive set, employing robust fitness evaluation metrics, and dynamically adjusting the evolutionary search through adaptive population control, local termination criteria, and elite retention mechanisms, the framework provides a rigorous and efficient approach to uncovering stochastic agent decision rules. This integrated methodology ensures both empirical fidelity and theoretical interpretability, laying a strong foundation for the subsequent analysis of evolved rule performance in the results section.

The code for our AGP framework, which extends the Evolutionary Model Discovery (EMD) codebase by Gunaratne & Garibay (2020), is available at this GitHub repository: https://github.com/Gayani-299/Adaptive_EMD_for_Stochastic_ABMs.git. All adaptations, including dynamic population sizing and elite-based restarts, are documented within the repository. The original EMD framework was designed for deterministic rule discovery; our version supports stochastic rule discovery and adaptive evolution in high-variability ABMs.

Results

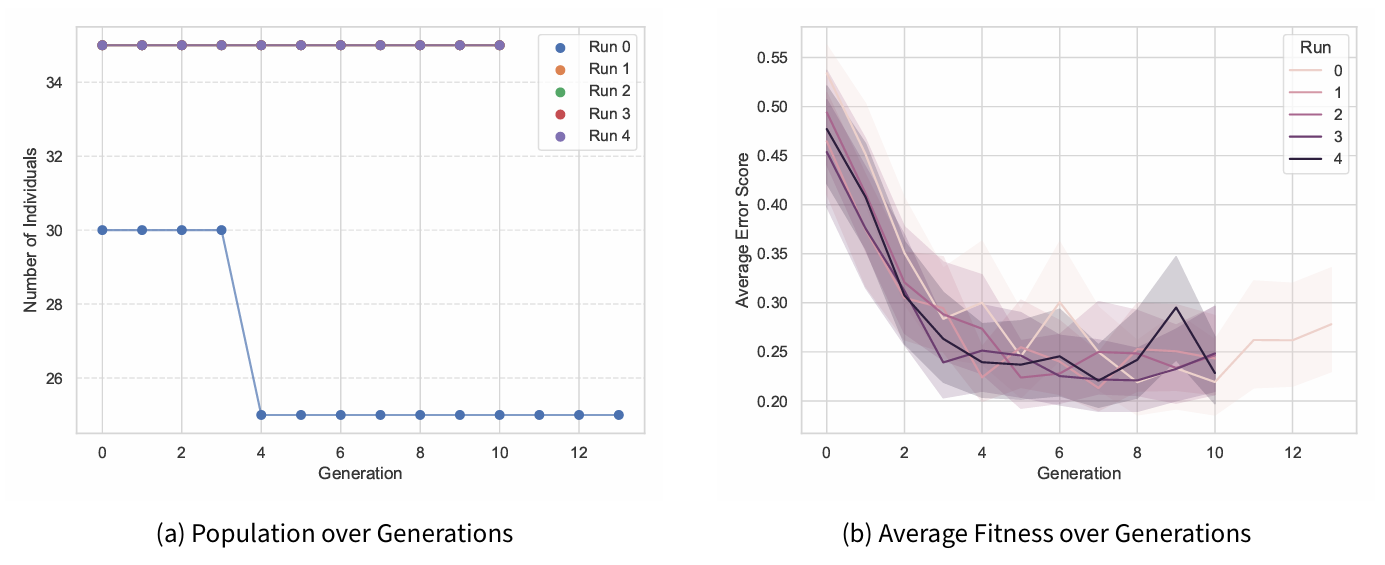

To evolve the exit selection rules within ABM, we conducted five independent runs of the AGP process. Each run was initialised with a population of 30 individuals, subject to a maximum of 50 generations. However, based on the local termination criterion, where evolution halts if no fitness improvement is observed over 10 consecutive generations, most runs concluded earlier. In addition, whenever a new best-performing rule was identified, the population size was adaptively reduced by five individuals, down to a minimum of five, to concentrate the search around promising solutions.

Figure 6 presents the evolution of (a) the average error score and (b) the number of individuals per generation across the five runs.

In Figure 6 (a), the average error score across generations shows a clear downward trend for all runs. During the initial generations, a steep decline in the error score is observed, indicating rapid identification and propagation of beneficial rule structures. As generations progress, the improvement rate gradually diminishes, reflecting a shift from broad exploration to fine-tuning of evolved solutions. Minor fluctuations in error scores are expected in later generations, given the underlying stochasticity of the simulation-based evaluation.

Figure 6 (b) illustrates the dynamics of the population size over generations. In one run (Run 0), a noticeable reduction in population size is observed after the third generation, corresponding to the discovery of a better-performing individual. Following this, the subsequent runs were reinitialised with a fresh population including elite individuals, resulting in the initial population size of 30 being maintained throughout these runs. As the best solution was already identified during the first run, the population remained stable in later replications, with no further reductions triggered. This dynamic adjustment reflects the AGP mechanism’s ability to conserve computational resources during active search phases while ensuring broad exploration during reinitialisations.

Together, these results demonstrate that the proposed AGP approach successfully promotes both rapid convergence towards high-quality exit selection rules and efficient utilisation of computational resources through adaptive evolution strategies.

The AGP-discovered rules consist of varying combinations of factors linked through addition operators. Although some evolved individuals produced deeper tree structures, the overall complexity was managed effectively through strong typing and a maximum tree depth limit. In many cases, the addition operators simply aggregated weighted primitives without unnecessary structural "padding", thus limiting the extent of tree bloat, a common challenge in genetic programming (Banzhaf & Langdon 2002; Gunaratne et al. 2023; Luke & Panait 2006). By setting depth constraints, tree bloat was kept within acceptable bounds, while providing non-critical sections where crossover operations could introduce new diversity without disrupting high-performing branches (Luke 2000).

Table 2 presents the simplified decision rules and the corresponding average errors for the five best-performing individuals produced by AGP. Notably, the most fitted rule, Exit = Randomly select based on (\({F_c}\) + \({F_d}\)), exactly recovers the pseudo-truth rule that originally generated the synthetic dataset, achieving the lowest average error score of 0.1840. This demonstrates that the evolutionary discovery process was successful in reconstructing the intended underlying behavioural mechanism.

| Run | Gen | Rule | Avg.Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | Exit = Randomly select based on (\({F_c}\) + \({F_d}\)) | 0.1840 |

| 3 | 3 | Exit = Randomly select based on (\({F_c}\)) | 0.1864 |

| 1 | 7 | Exit = Randomly select based on (\(2{F_c}\) + \({F_d}\)) | 0.1867 |

| 3 | 2 | Exit = Randomly select based on (\(2{F_d}\)) | 0.1903 |

| 0 | 3 | Exit = Randomly select based on (\(2{F_c}\)) | 0.1906 |

Across the top-performing rules, CompareCrowd (\({F_c}\)) and CompareDistance (\({F_d}\)) consistently appear as dominant factors influencing exit selection, either individually or in combination. Minor variations, such as the double of crowd factors (\(2{F_c}\)) or distance factors (\(2{F_d}\)), were observed among near-optimal individuals, suggesting slight refinements in how agents weight environmental information. However, the emergence of \({F_c}\) and \({F_d}\) in all five rules confirms their critical role in shaping realistic evacuation dynamics within the StationSim environment. Furthermore, the close clustering of error scores among the top individuals (all below 0.19) reflects a robust and consistent convergence of the evolutionary search towards plausible behavioural hypotheses.

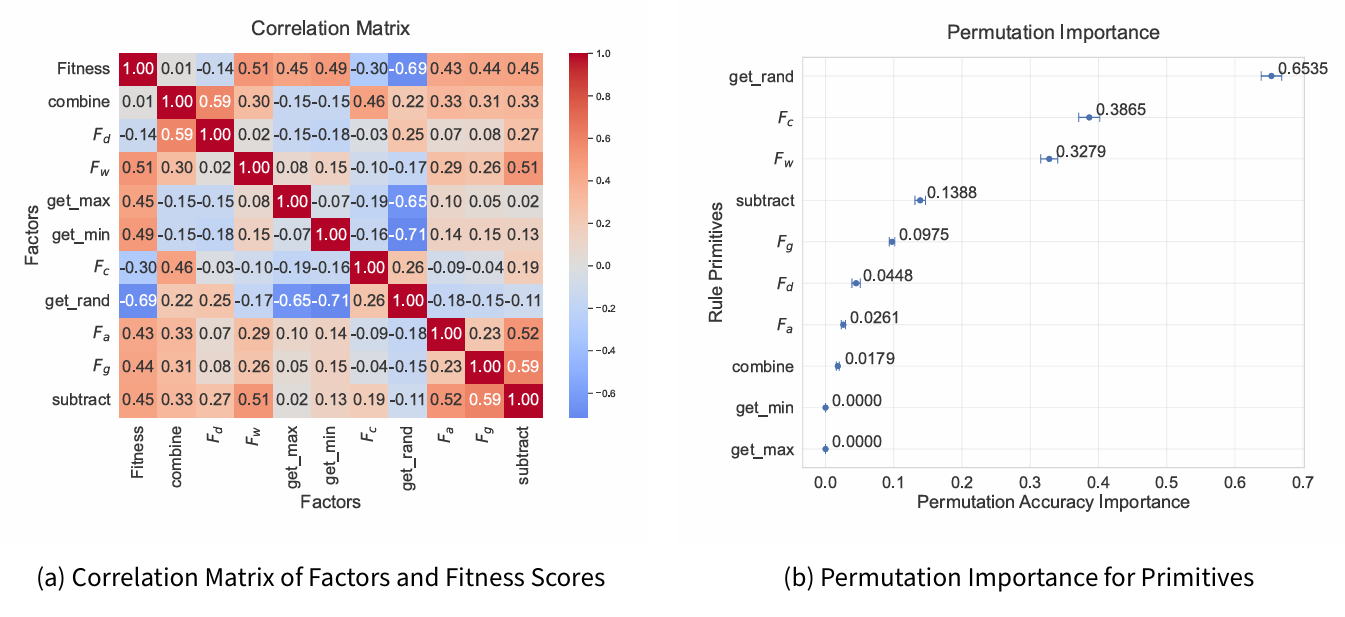

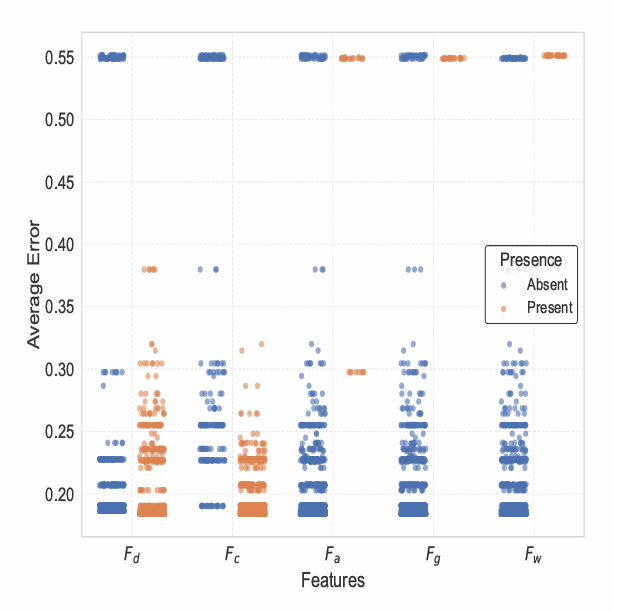

The feature importance analysis shown in Figure 7 provides key insights into the relationships between evolved rule primitives and model fitness across all discovered individuals.

The correlation matrix in Figure 8 highlights the strength and direction of the associations between the rule components and the final fitness score (average error). Fitness shows the strongest negative correlation with the get_rand (random selection) primitive (-0.69), confirming that models incorporating greater stochastic elements tended to achieve lower error scores. This aligns with the nature of the pseudo-truth rule, which stochastically selects exits based on environmental factors. Moderate negative correlations are also observed between fitness and spatial factors such as compare_crowd (\({F_c}\), -0.30) and, to a lesser extent, compare_distance (\({F_d}\), -0.14), suggesting that rules that leverage proximity and crowd awareness contributed meaningfully to model performance.

Positive correlations between fitness and primitives such as get_max, get_min, and subtract suggest that greater reliance on deterministic comparator structures tends to degrade fitness, probably due to deviation from stochastic ground-truth behaviour.

Complementary to the correlation analysis, the results of permutation importance shown in Figure 7 quantify the marginal contribution of each primitive to prediction accuracy. The get_rand primitive exhibits the highest permutation accuracy importance (0.6535), reinforcing its role as the most critical in approximating the target behaviour.

Interestingly, \({F_c}\) (crowding at exits) and \({F_w}\) (exit width) are ranked as the second and third most important primitives, with permutation scores of 0.3865 and 0.3279 respectively. This suggests that spatial factors related to congestion and capacity significantly influenced the exit selection dynamics. However, \({F_d}\) (distance) demonstrates lower importance (0.0448) relative to width. This outcome can be explained by the nature of the permutation importance, which is averaged across all evolved rules—including poor-performing or highly stochastic individuals. In these suboptimal models, spatial width may have been leveraged more consistently than distance, artificially increasing its relative importance compared to \({F_d}\).

Additionally, the permutation scores for the primitives \({F_a}\) (age) and \({F_g}\) (gender) are notably low (below 0.1), implying a limited influence on overall model performance, consistent with their sparse appearance in the best-performing rules listed in Table 2.

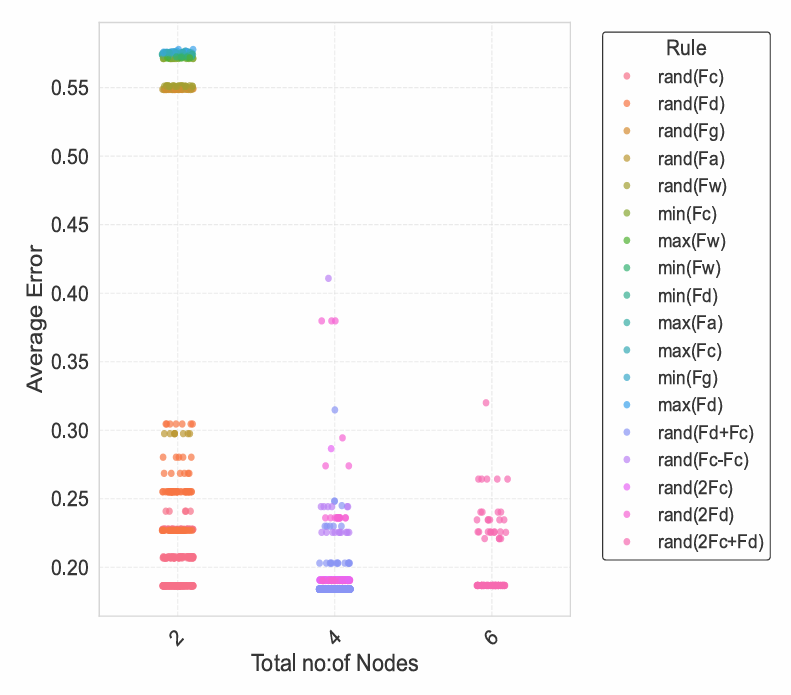

Figure 8 explores the relationship between rule complexity and model performance among the most frequently generated exit selection rules. The x-axis represents the total number of nodes within each simplified decision tree, serving as a proxy for rule complexity, while the y-axis depicts the corresponding average error score. Each point, colour-coded by rule type, represents a distinct evolved individual.

The results reveal a clear pattern, rules comprising 4 or 6 nodes generally achieve lower average errors compared to simpler 2-node structures. Although some 2-node rules attain moderate performance, the most accurate rules, particularly those combining multiple primitives such as \({F_c}\) and \({F_d}\), cluster around higher complexity levels. This suggests that while simple decision structures can capture basic behavioural tendencies, accurately approximating the stochastic pseudo-truth behaviour benefits from a moderate increase in rule complexity.

Notably, there is no strict linear relationship between complexity and performance. Beyond a certain point (4–6 nodes), increasing complexity does not necessarily yield substantial improvements in fitness, with performance plateauing. This indicates that the AGP successfully captured the essential components of the target behaviour without inducing unnecessary overfitting or excessive structural bloat. Such results align well with the principle of parsimony in modelling, favouring simpler but sufficiently expressive models (Coelho et al. 2019).

The presence of multiple rule structures achieving similarly low error rates across different complexity levels also highlights the flexibility and robustness of the evolutionary search. Rather than converging narrowly onto a single optimal rule, the AGP identified several viable approximations of the original stochastic rule, reflecting the inherently multi-modal nature of plausible behavioural explanations.

Figure 9 examines the impact of the feature presence on the average error distribution among the most frequently evolved exit selection rules. The x-axis lists the five primary factors (\(F_d\), \(F_c\), \(F_a\), \(F_g\), \(F_w\)), while the y-axis shows the corresponding average error scores. Each point represents a single evolved individual, coloured by the presence (orange) or absence (blue) of the corresponding feature in its decision rule.

Overall, the results indicate that the presence of \(F_d\) (distance) and \(F_c\) (crowd density) tends to be associated with a lower average error compared to their absence. This finding reinforces the critical role of spatial awareness—particularly proximity and congestion—in accurately replicating the pseudo-truth behaviour. In contrast, the presence of \(F_a\) (age similarity) exhibits minimal influence on the error, with overlapping distributions between present and absent cases. This suggests that social affinity features played a relatively minor role in optimising exit selection rules in this stochastic environment.

Interestingly, \(F_w\) (exit width) shows a near-neutral effect. While width appeared moderately important in the permutation importance analysis (Figure 7), its presence does not strongly differentiate high- from low-performing rules here. This apparent discrepancy arises because the permutation importance averages over all discovered rules, including suboptimal ones, while Figure 9 focusses on the most frequently generated and generally better-performing individuals.

Additionally, consistent with observations in Figure 8, a subset of deterministic rules exhibited higher error scores above 0.3. This reflects that they can lead to poor approximations of the pseudo-truth rule. Randomised selection mechanisms that involve both \(F_c\) and \(F_d\) together proved necessary to achieve the best fitness outcomes.

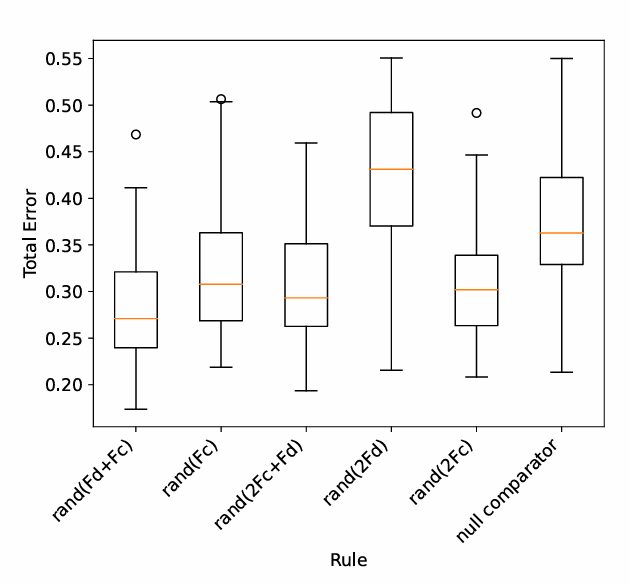

Figure 10 compares the robustness of six frequently evolved decision rules by evaluating their performance over 50 independent simulation runs. Each rule is assessed using the total average error (fitness), and the distribution is visualised through boxplots. The inclusion of a baseline "null comparator" rule, which assigns equal selection probability (0.5) to both exits. This offers a critical benchmark for interpreting the informativeness of the target patterns.

The rule rand(Fd+Fc) which corresponds to the pseudo-truth used to generate the synthetic dataset, exhibits the lowest median error and one of the narrowest interquartile ranges, confirming both its accuracy and consistency. This result validates that the AGP was successful in recovering the true generative mechanism. In comparison, rules such as rand(2Fc), rand(2Fc+Fd), and rand(Fc) also achieve low median errors, indicating that multiple behavioural formulations incorporating crowd-based heuristics can approximate target patterns with similar fidelity.

Interestingly, the distance-only rule rand(2Fd) performs worse than the null comparator, which assigns equal probabilities (0.5) to both exits. This outcome appears counterintuitive at first, as one might expect a rule that favours the closer exit (twice as likely) to outperform a purely random choice. However, this result becomes clearer when considering the structure of the pseudo-truth data. The synthetic target dataset was generated using a stochastic rule that combines distance and crowding (Fd + Fc), reflecting agents’ tendencies to select the less crowded and closer exit. This behaviour is dynamic and context-sensitive: the attractiveness of an exit is not static but is influenced by both spatial proximity and evolving congestion levels. The rand(2Fd) rule, however, imposes a rigid and strongly amplifying distance factor while entirely ignoring crowding. This misalignment leads agents to disproportionately favour exits that may be physically closer but congested, thereby diverging from the pseudo-truth pattern in both flow rate and timing.

In contrast, the null comparator, despite its lack of environmental awareness, introduces uniform randomness in exit selection. This baseline randomness unintentionally mimics some of the stochastic dispersion in the pseudo-truth data, particularly in early stages of the simulation when crowding differences across exits are not yet strongly differentiated. As a result, while the null comparator lacks explanatory power, its averaged behaviour introduces less structural bias than the misaligned rand(2Fd) rule, leading to lower mean error in approximating the overall synthetic pattern.

To evaluate the robustness of the AGP method, we performed a sensitivity analysis by varying the main parameters unique to the adaptive mechanism, including the dynamic population resizing strategy and local termination threshold. All other standard GP parameters (mutation, crossover, selection) were held constant to isolate the effects of adaptivity. We report the average fitness and convergence characteristics under different configurations to assess both the efficiency and consistency of the AGP search process.

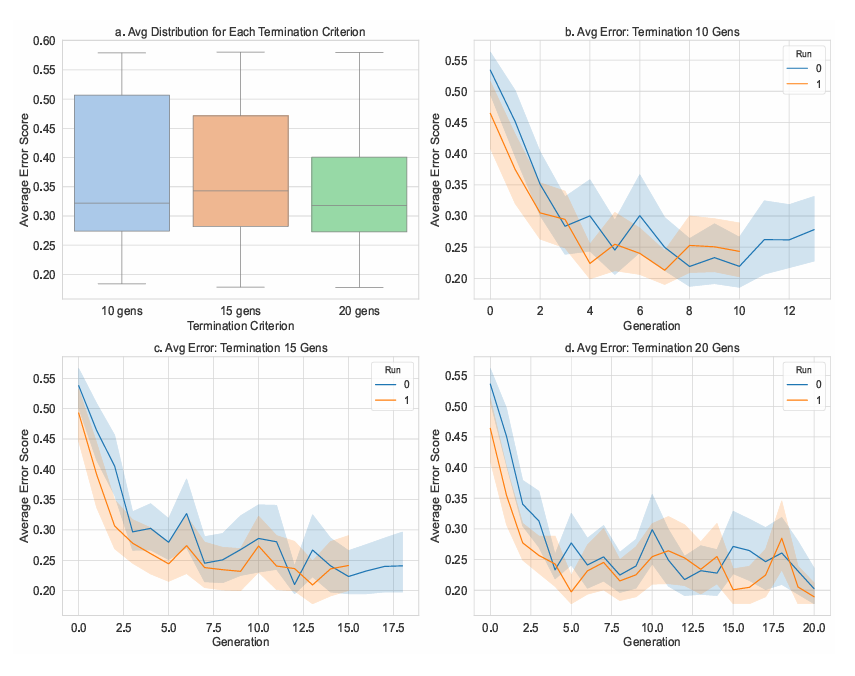

Figure 11 illustrates the sensitivity of the adaptive genetic programming framework to different local termination thresholds, defined as the number of generations with no improvement in best fitness before restarting the run. Specifically, we compare performance under thresholds of 10, 15, and 20 generations, with each configuration repeated across two independent IGSS runs.

Subfigure (a) presents the distribution of the final fitness values across all individuals generated in each setting. A clear improvement in fitness is observed as the termination threshold increases. While the 10-generation setting exhibits higher variance and a higher median error, the 20-generation configuration shows both lower average error and reduced dispersion, suggesting more reliable convergence and solution quality.

Subfigures (b)-(d) show convergence curves across generations for each termination condition. Notably, the 20-generation setting (d) demonstrates a smoother and deeper error reduction, particularly beyond generation 10, indicating that longer patience before termination allows for further exploration and refinement of candidate solutions. In contrast, the 10-generation runs (b) appear to terminate prematurely, often plateauing early or oscillating, suggesting that the search space may not have been sufficiently explored.

While the local termination criterion in our adaptive GP was set at 10 generations without improvement, this does not limit the global search capacity of the method. The algorithm performs five adaptive runs, each using the best individuals (elite set) from the previous run to guide the next. This restarts the search process from a locally optimised point, allowing continued exploration of the solution space. As such, the full model discovery process spans at least 50 generations in total, ensuring broad coverage and reducing the risk of premature convergence. Further, the main objective of stochastic model discovery using AGP is to give priority to stochatic model evaluation for many simulation runs to calculate more robust average error value and to keep the GP inherited computation lower. This approach is consistent with multi-start evolutionary algorithms and memetic optimisation strategies that leverage guided restarts for an efficient global search (Blum & Roli 2003; Martı́ et al. 2013). While sensitivity analysis suggests that longer local patience (e.g., 20 generations) may improve solution quality, the current setup provides a pragmatic balance between exploration depth and computational efficiency.

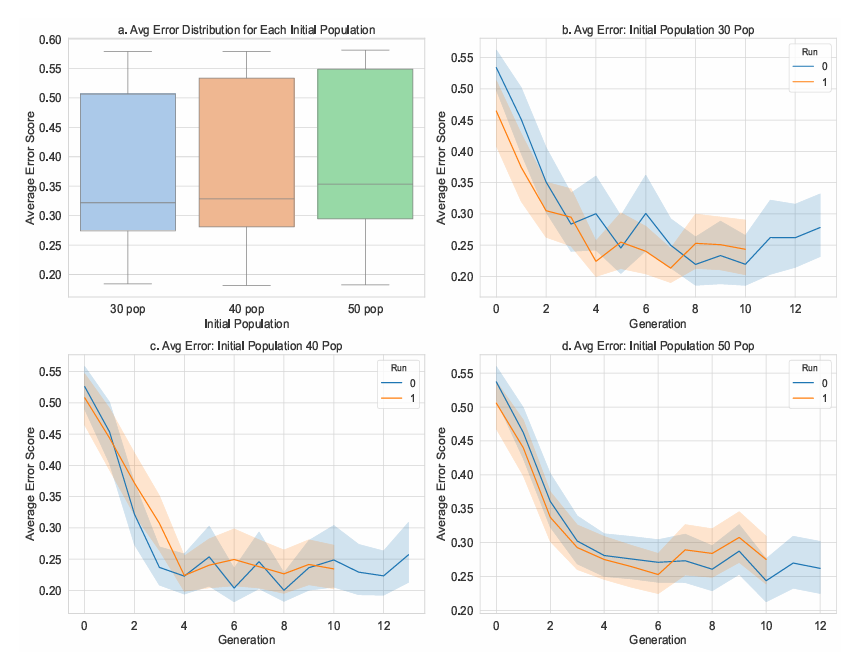

Figure 12 examines the effect of varying the initial population size on the performance of the AGP framework. Three initial sizes were tested: 30 (baseline), 40, and 50 individuals. Each configuration was run for two independent IGSS discovery runs and the local termination was fixed at 10 generations without improvement.

Subfigure (a) compares the distribution of the final fitness scores across all individuals generated throughout the runs. While higher initial population sizes (40 and 50) naturally produce more individuals, the overall distribution of fitness scores does not improve substantially with increasing population. In fact, the median and lower quartiles of the 30-population configuration remain competitive. This suggests that a smaller initial population may be sufficient for the AGP framework to find near-optimal local solutions, especially when elite retention and restarts enable broader exploration across multiple runs.

Subfigures (b–d) show the convergence behaviour of each setting across generations. Interestingly, all three configurations quickly reduce the average error within the first few generations. In the 30-population setting (b), both runs converge toward local optima by generation 5–6 and maintain stable error thereafter. The same pattern is observed for populations of 40 and 50, though with slightly smoother error decline in later generations (especially in subplot d).

These results highlight that increasing the initial population size does not linearly improve the convergence or quality of the final model. The adaptive restart mechanism, combined with elite retention, appears to allow even smaller populations to achieve competitive results. Additionally, larger populations may increase the computational load without proportionate gains in solution quality. This supports the use of 30 as a pragmatic default, offering an effective balance between search diversity and computational efficiency.

Conclusion

This study introduced an Adaptive Genetic Programming (AGP) framework within the Inverse Generative Social Science (IGSS) paradigm, specifically tailored to identify stochastic rules for Agent-Based Models (ABMs). By explicitly incorporating stochastic and deterministic decision primitives, the AGP successfully discovered generative behavioural rules that reproduced complex, emergent pedestrian behaviours observed in the StationSim environment.

Critically evaluating the discovered rules, our analysis confirmed that AGP effectively recovered the original pseudo-truth rule (rand(Fd+Fc)), demonstrating the model’s capability to discover accurate generative explanations. The rules evolved consistently prioritised the crowding (Fc) and distance (Fd) factors, aligning with previous findings that highlight the importance of these factors in pedestrian dynamics (Malleson et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). The significantly inferior performance of the purely distance-based rule (rand(2Fd)) compared to the null comparator underscores the critical role of crowding as a primary driver of realistic exit selection behaviours, further reinforcing previous empirical and simulation-based insights into pedestrian dynamics (Kinateder et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2022).

The analysis of robustness across multiple simulation runs revealed that while multiple rules that incorporate both crowd and distance factors performed similarly well, suggesting equifinality, rules neglecting the crowding factor demonstrated notably poorer and more variable outcomes. This outcome is consistent with recent IGSS research, emphasising the necessity of integrating multiple environmental and social considerations to capture complex human behaviours effectively (Miranda et al. 2023; Vu et al. 2023). Moreover, the AGP’s adaptive features, including dynamic population sizing, local termination criteria, elite individual retention, and guided fitness updates, significantly contributed to computational efficiency and improved solution quality. These adaptive strategies align with successful adaptive mechanisms demonstrated in other evolutionary computation applications (Mao et al. 2021; Zachariah et al. 2023).

Interestingly, our permutation importance analysis indicated discrepancies between the factors’ overall importance when averaged across all evolved rules and their specific contributions within optimal rule structures. Although exit width (Fw) appeared relatively important in permutation analyses, it showed minimal differentiation in terms of rule effectiveness. This highlights a critical caveat in permutation-based feature importance methods, as averaging across suboptimal and optimal rules may distort perceived factor significance, echoing concerns raised in recent methodological critiques of feature importance analysis (Liu & Motoda 2012).

Sensitivity analysis provided valuable insights into parameter impacts on the AGP’s performance, particularly highlighting the effectiveness of the chosen termination criterion. A longer threshold (20 generations) allowed deeper exploration and refinement but incurred increased computational costs, aligning with prior findings advocating balanced exploration-exploitation strategies (Eiben & Schippers 1998; Martı́ et al. 2013). Similarly, variations in initial population size demonstrated limited gains beyond a certain point, affirming that computational efficiency can be maintained without compromising discovery quality by moderate population sizes.

Despite these promising outcomes, several limitations and opportunities for future research remain. First, the synthetic pseudo-truth dataset, while controlled, lacks the complexity of real-world data, potentially oversimplifying agent heterogeneity and contextual variability. Thus, validating the AGP framework against empirical pedestrian datasets from diverse real-world scenarios represents an essential next step. Additionally, future work could explore expanding the primitive set to incorporate more nuanced social and emotional factors, further enhancing behavioural realism.

Moreover, extending this approach to multi-objective optimisation, explicitly balancing accuracy, complexity, and interpretability may provide additional insights and more actionable rules for stakeholders (Vu et al. 2020, 2023). Exploring advanced techniques for controlling GP bloat without overly constraining evolutionary diversity also presents an intriguing methodological advancement. Finally, generalising the proposed AGP methodology to other stochastic social systems beyond pedestrian modelling could further demonstrate its versatility and broader applicability within computational social science.

Future extensions could also explore the use of adaptive population resizing not only during evolution but also across runs, potentially conditioned on search progress or rule diversity. Additional analysis using computational budget normalisation (e.g., fixed total evaluations) may further clarify the trade-offs between population size and search depth.

In conclusion, the adaptive evolutionary IGSS approach presented here offers a powerful framework for systematically discovering robust, interpretable, and empirically grounded stochastic ABM rules. Through adaptive mechanisms and comprehensive validation, AGP effectively navigates complex search spaces, uncovering generative behavioural rules capable of realistically simulating emergent phenomena. These findings affirm the potential of AGP to advance computational methodologies in social science and underscore the importance of balancing computational efficiency, behavioural realism, and interpretability in future IGSS studies.

Appendix A: StationSim Model Description (ODD Protocol)

The model description follows the ODD (Overview, Design concepts, Details) protocol (Grimm et al. 2020).

1. Purpose and Patterns

The StationSim ABM simulates pedestrian behaviour within a railway station environment to investigate the emergent congestion patterns arising from local interactions and exit choice decisions. This ABM specifically supports Inverse Generative Social Science (IGSS) by generating pseudo-truth data against which candidate behavioural rules can be tested.

2. Entities, State Variables, and Scales

Entities

- Agents: Represent individual pedestrians in a station.

- Model (Environment): A global controller that contains simulation settings, agents, time, and boundaries with exits and entrances.

State Variables. Agents:

| Variable | Description | Type | Static/Dynamic | Range/Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

unique_id |

Identifier for the agent | Integer | Static | 0 to N |

location |

Current position in 2D space | Array[2] | Dynamic | Within bounds |

loc_desire |

Exit gate location | Array[2] | Static | coordinates |

loc_start |

Entrance gate location | Array[2] | Static | coordinates |

gate_in |

Index of entrance gate used | Integer | Static | [0–2] default |

age |

Age of the agent | Integer | Static/random | [10-70] |

gender |

Gender identifier | Integer | Static/random | Typically [0, 1] |

speed |

Current speed | Float | Dynamic | \(\leq \texttt{speed\_max}\) |

speeds |

List of possible movement speeds | List[Float] | Static | Descending order |

status |

Agent status: inactive, active, finished | Integer | Dynamic | 0, 1, 2 |

wiggle |

Wiggle step size for avoidance | Float | Static | Small positive |

Environment:

| Variable | Description | Type | Default Value |

|---|---|---|---|

agents |

List of all agents in the model | List[Agent] | |

pop_total |

Total number of agents | Integer | 100 |

pop_active |

Number of currently active agents | Integer | |

pop_finished |

Number of finished agents | Integer | |

step_id |

Current simulation step | Integer | |

speed_max |

Max desired speed | Float | 1 |

speed_min |

Min desired speed | Float | 0.2 |

speed_mean |

Mean speed used for speed_step calc | Float | 1 |

speed_steps |

Number of speed levels to avoid collision | Integer | 3 |

boundaries |

Environment boundaries | np.array | [0,0], [150, 100] |

gates_in |

Number of entrance gates | Integer | 3 |

gates_out |

Number of exit gates | Integer | 2 |

gates_locations |

All entrance and exit gate coordinates | Array | |

gates_width |

Size of exit gates | Array | [1, 2] |

separation |

Minimum allowed distance to avoid collisions | Float | 1 |

max_wiggle |

Maximum sideways wiggle | Float | 1 |

no_waves |

Number of train arrival waves | Integer | 3 |

train_delay |

Time step delay between waves | Integer | 30 |

tree |

Spatial tree (KDTree) for proximity queries | KDTree | |

random_seed |

RNG seed for reproducibility | Integer | |

Scales

- Spatial: Continuous 2D space with width = 150 and height = 100. Agents and gates use real-number coordinates.

- Temporal: Discrete time steps, each representing approximately 1 second of real-world time.

- Spatial Units: Units not explicitly defined in real-world terms (e.g., meters), but conceptually represent station dimensions.

- Agent Scale: 100 agents by default; designed for crowd behaviour in a bounded environment.

3. Process Overview and Scheduling

Model Processes. The StationSim model executes the following sequence of actions at each discrete simulation time step:

- Spatial Index Update (Model):

- The environment updates the spatial index (

cKDTree) based on current agent locations. - State variables updated: None directly; supports collision checks.

- The environment updates the spatial index (

- Agent Processes (All agents, arbitrary order):

- Activation (Agent.activate):

- Agents become active once the current step exceeds their activation step.

- State variables updated:

agent.status,agent.step_start,model.pop_active.

- Movement and Collision Checking (Agent.move):

- Active agents compute desired movements towards their intended exits.

- Exits are dynamically updated at each simulation step based on the exit selection rule which is based on distance to exit and the crowdedness at each exit (refer Section 7: Submodels)

- Agents test speeds iteratively to avoid collisions.

- If blocked, agents perform a "wiggle" maneuver.

- State variables updated:

agent.location,agent.speed, collision and wiggle histories (agent.history_collisions,agent.history_wiggles,model.history_collision_locs,model.history_wiggle_locs).

- Boundary Check and Adjustment (Model.re_bound):

- Agents’ locations are adjusted to stay within model boundaries.

- State variables updated:

agent.location.

- Delay Calculation (Agent.move):

- Agents calculate delays based on expected versus actual travel times.

- State variables updated:

model.steps_delay.

- Deactivation (Agent.deactivate):

- Agents deactivate upon reaching their exit gates.

- State variables updated:

agent.status,model.pop_active,model.pop_finished,model.get_evacuation_time.

- Activation (Agent.activate):

- Data Collection (Model):

- Exit choices and delays are recorded.

- History Update (Agents and Model):

- Agent locations and states are logged if history tracking is enabled.

- Simulation Step Increment (Model):

- The simulation step counter increments by one.

- State variables updated:

model.step_id.

Scheduling Order and Updates. Agents execute actions asynchronously, meaning each agent’s update potentially influences subsequent agents within the same step.

Rationale for Processes and Scheduling. Agent activation and deactivation reflect realistic pedestrian flows through entry and exit gates. Movement and collision logic mimic pedestrian navigation and congestion. Asynchronous updating captures realistic immediate interactions among agents, essential for accurately modeling congestion dynamics.

4. Design Concepts

Basic Principles

StationSim is designed to simulate pedestrian dynamics in a train station environment. It models how individuals (agents) move from entrance gates to exit gates using basic rules for exit selection, movement, and collision avoidance.

Underlying idea: Individual movement rules, when applied in a spatially explicit setting with dynamic exit selection, give rise to emergent patterns such as congestion and overall evacuation time. Local interactions among heterogeneous agents produce emergent macro-level congestion patterns.

Emergence

Emergent Outcomes: The overall evacuation delay, collision patterns, and exit choice distributions; they emerge from each agent’s local decisions and interactions. Imposed Elements: The spatial layout (station dimensions and fixed gate positions) is predetermined, setting the stage for emergent crowd dynamics.

Adaptation

Agents dynamically adapt their movement (speed, direction) in response to local congestion.

Agent Behaviour: Agents adapt by adjusting their movement speed based on local conditions. When a collision is detected, they iteratively try slower speeds.

Wiggle Mechanism: If even the slowest speed still causes a collision, agents perform a ‘wiggle’—a random vertical displacement—to try to clear the blockage.

Heterogeneity Influence:

- Explanation: Not all agents are identical. Differences in their maximum speed, personal space (separation distance), and possibly physical characteristics (like age) can lead some agents to encounter more collisions.

- Effect on Wiggle: Agents with lower preferred speeds or higher collision sensitivity may trigger the wiggle behaviour more frequently. This heterogeneity can contribute to varying delays among agents.

Objectives

Primary Objective: Each agent’s goal is to exit the station as quickly as possible. This objective drives their movement decisions and exit gate selection.

Decision Basis: Agents compare the attributes such as distance to exit and croededness at each exit to choose an exit, indirectly optimising their route based on local conditions.

Learning

No Learning Implemented: The model does not incorporate any mechanism for agents to change their decision rules based on past experiences. Behaviour is entirely rule-based.

Prediction

Implicit prediction is assumed as agents select exits based on perceived current crowdedness and distance.

Sensing

Agents perceive distances to exits and the number of neighboring agents within their immediate vicinity.

- Mechanism: Agents use a spatial query (via a cKDTree) to detect neighbors within a 20-unit radius.

- Accuracy: They have precise information about the distances and characteristics (e.g., age, gender) of nearby agents.

- Implication: This assumption of perfect sensing means that agents’ movement and collision-avoidance decisions are based on accurate, real-time data.

Interaction

Direct interaction is modeled via collision avoidance behaviours. These local interactions lead to broader patterns such as emergent delays and congestion. Mediated interaction occurs through shared environmental congestion.

Stochasticity

Agent arrival timing, individual characteristics (age, gender, speed), and probabilistic exit selection decision rules introduce stochasticity. The wiggle displacement is chosen randomly when needed. Stochasticity ensures variability in outcomes and helps simulate the unpredictability observed in real crowds.

Observation

No Explicit Collectives: The model does not group agents into explicit collectives; however, aggregate patterns (such as queues or clusters) emerge naturally from individual interactions.

Observation

Output Data: The model tracks evacuation times, collision counts, agent trails, and exit selections. These metrics are collected and later analyzed to understand both individual and emergent system behaviours. Analysis Purpose: The observations serve to validate the model against expected patterns in crowd movement and to identify the effects of local interactions on overall performance.

5. Initialisation

- Population size: The model initialises with 100 agents by default, but this can be customised.

- Agent entrances: Each agent is randomly assigned to one of the three predefined entrance gates. Assignment occurs before the simulation begins. To prevent agents from overlapping exactly at their starting point, each agent’s y-coordinate is slightly shifted using a uniform random perturbation

- Agent activation times: Agents are not initialised to enter the simulation at the same time. Instead, each agent is assigned a unique activation step to simulate realistic crowd inflows such as those resulting from multiple train arrivals. This is implemented through a two-stage stochastic process. First, a wave interval is selected based on a uniform random draw across the total simulation duration. These wave intervals are predefined using a list of time bins (default: three waves with approximately 30-second spacing). After selecting a wave, a further delay is added using a random sample from an exponential distribution, which skews agent entry times so that most agents in a wave enter early but some arrive later. This creates variability within each wave while maintaining clustered arrival patterns overall. The result is a temporally distributed sequence of agent activations that enhances realism by preventing artificial synchrony.

- Stochastic assignment of agent attributes:

- Age: Drawn randomly from an uniform range, typically representing adult ages (e.g., 10–70).

- Gender: Assigned randomly using a Bernoulli distribution with equal probability (0.5) for male or female by default, unless otherwise specified.

- Maximum speed: Each agent’s maximum speed is drawn from a normal distribution (mean = 1.0, std = 1.0). However, to avoid unrealistic values (e.g., zero or negative speeds), any sampled value below the model-defined minimum speed threshold (default: 0.2) is rejected, and the process is repeated until a valid value is obtained. Speed values are then discretised into a set of preferred “speed steps.”

- Agent locations: Each agent is initially positioned at the coordinate of a randomly assigned entrance gate. Separately, each agent’s target exit gate is dynamically selected during the simulation using a probabilistic rule that considers factors such as the distance to each exit and the level of congestion around them. This target exit is re-evaluated at each time step, allowing the agents to reroute based on changing environmental conditions, including collision avoidance (wiggle movements). This reflects adaptive behaviour rather than pre-defined routing.

- Randomness and reproducibility: Initialisation uses a random seed, either user-provided or drawn from

os.urandom. This enables reproducibility when needed. - Environment setup: The station dimensions are 150 units wide and 100 units high. Boundaries are set accordingly. Entrance and exit gates are hardcoded in fixed positions.

- History tracking (if enabled): If

do_history = True, internal structures to track locations, collisions, and delays over time are initialised.

6. Input Data

The model does not incorporate any external data sources. Instead, all the initial conditions, parameters, and environmental settings are hard-coded as default values by the modeller. The model is self-contained. Although the current implementation does not use empirical or externally sourced data, the structure allows for future modifications where external data could be integrated if needed.

7. Submodels

This section provides detailed descriptions of all submodels included in the StationSim agent-based model.

Exit Selection Submodel (Pseudo-truth rule to generate synthetic data for evaluating IGSS generated models) The Exit Selection Submodel determines which exit an active agent chooses during each simulation step. The model evaluates two primary factors for each exit:

- Distance: The Euclidean distance between the agent’s current location and the exit.

- Crowding: The level of congestion, quantified by the number of active agents within a given radius of the exit.

These factors are computed separately, combined into a composite score, and then normalized to yield a probability distribution over the available exits. The agent then selects an exit based on these probabilities.

Mathematical Formulation: For a given agent \(j\) and each exit \(i\), let:

- \(d_{i,j}\) denote the Euclidean distance from agent \(j\) to exit \(i\).

- \(n_i\) denote the number of active agents (agents with status \(1\)) within a specified radius of exit \(i\). To avoid division by zero, if \(n_i = 0\), a small constant (e.g., \(0.1\)) is used instead.

Distance Factor: The distance factor is computed by taking the inverse of the distance:

| \[D_{i,j} = \frac{1}{d_{i,j}}\] | \[(7)\] |