The Doctrinal Paradox in Deliberative Process and in Majority Voting

aCentre for Logic and Philosophy of Science, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (4) 2

<https://www.jasss.org/28/4/2.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5751

Received: 13-Jan-2025 Accepted: 07-Jul-2025 Published: 31-Oct-2025

Abstract

This paper proposes a new approach analyzing to the doctrinal paradox by considering a deliberative process (which can be represented by an agent-based model) in comparison with classical (binary) majority voting and an aggregation of (continuous) degrees of belief prior to majority voting. This model is a multivariate extension of the Hegselmann-Krause opinion dynamics model. From a quantitative comparison of the final sentences resulting from a (binary and continuous) majority-voting and deliberative method, several results emerge. First, for a small jury, binary majority voting leads to the doctrinal paradox less often than continuous majority voting and the interaction process. Second, when the jury gets bigger, letting the jury members interact minimizes the occurrence of the doctrinal paradox. Third, once agents respect the principle of reason for updating their opinions, they can totally avoid the doctrinal paradox, which is impossible with majority voting. Fourth, we notice that even if sometimes the majority-voting and the deliberative process produce the same rate of occurrence of the paradox, it does not imply that their verdict will be the same for a given trial: the verdict differs in maximum 25% of the time for small juries, but this discrepancy fades out for larger juries.Introduction

The doctrinal paradox originates from the jurisprudential literature (Kornhauser & Sager 1986, 1993). This ‘paradox’ occurs when a court constituted of several members has to make decisions based on a law doctrine. It has been generalized later on by Pettit & Rabinowicz (2001) under the name of ‘discursive dilemma’. For the authors, every deliberative democracy faces a dilemma when its members adopt some principle of reason and a majority voting process to guide their decision to avoid any arbitrary authority or domination.

As an illustration, consider a court of law consisting of three judges entitled to determine the culpability of a defendant. In order to do so, they have to give their judgment about three propositions:

x) The defendant performed a certain action (i.e., there is compelling evidence against the defendant); y) The defendant has a contractual obligation not to perform that action (i.e., this action is prohibited by law); z) The defendant is guilty.

For the sake of logic and fair justice, each judge guides their reasoning in accordance with a particular principle of reason: the truth value of the third proposition should be the consequence of the two previous ones and hence be ‘true’ if and only if the former two are. In other words, the third judgment \(z\) must be the logical conjunction of the two previous ones \(x\wedge y\). Furthermore, in order to obtain an impartial sentence, at the end of the hearing, each judge is isolated and has to write down their truth values about the three propositions on a piece of paper and put it in a ballot box. Votes are counted, and the final truth value of each proposition is determined according to a majority voting procedure. However, in some cases, this voting procedure leads to inconsistencies. A special configuration (a possible world) involving three judges is depicted in Table 1.

| x | y | z | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Judge 1 | True | True | True |

| Judge 2 | True | False | False |

| Judge 3 | False | True | False |

| Majority | True | True | False |

In this example, notice that, although each judge draws their conclusion with a principle of reason (in this case, \(z\) and \(x\wedge y\) have the same truth value), the group as a whole adopts a conclusion in contradiction with this principle of reason. In such a situation, the group ceases to be an agent driven by a principle of reason and to be conversable: the group is incapable — on its own — of rationally justifying its conclusion by its premises (i.e., \(x\) and \(y\)). However, a positive aspect of this procedure is that the group’s conclusion will be the same as that of the majority of its members. This aggregation strategy is called the conclusion-driven approach: the members are individually compliant with the principle of reason but the group, as a whole, may accept an irrational set of propositions (i.e., violating the principle of reason at the aggregate level).

To preserve the group’s conversable nature, one can instead propose that the group’s conclusion be given by the conjunction of the premises alone, even if the majority of the members disagree with this conclusion. In our case, the group — as an autonomous agent — would argue that the defendant is guilty because both premises (computed by majority voting) are true. In this premise-driven approach, the society as a whole is compliant with its principle of reason and can adopt a conclusion that the majority of its members refuse.

In this example, we catch the gist of the doctrinal paradox. When adopting a majority voting procedure, every deliberative democracy (such as a court of justice) faces a discursive dilemma: shall it adopt a conclusion-driven approach to save the majority of agent’s stake on the conclusion and to sacrifice group’s conversable nature, or adopt a premise-driven approach to preserve the latter and sacrifice the former? Stated differently by Pettit & Rabinowicz (2001 p. 277): "the question raised by the discursive dilemma is whether this discipline of reason is meant to apply to individuals, taken separately, or to the group as a whole".

List (2011, Chapter 2) proved that such kinds of dilemmas are inherent to any aggregation function (i.e., a procedure that receives the members’ opinions as input and produces the group’s opinion as an output). In the context of deliberative democracy, there are other legitimate ways of aggregating opinions besides majority voting, such as progressively reaching a consensus thanks to public debate and dialogue without invoking any voting procedure. We explore this possibility left open by Pettit & Rabinowicz (2001) and see to which extent such democracies are facing the discursive dilemma. Indeed, one can expect that a debating jury will behave more as a coherent group and thus be less likely to face the doctrinal paradox. In this paper, we will study this alternative quantitatively by implementing an agent-based opinion dynamics model.

In general, agent-based models represent interactions between autonomous agents. Such models find relevant applications in various disciplines such as marketing, supply chain, epidemiology, economics, and social sciences. These models have particularly gained attention in the field of social epistemology (e.g., Aydinonat et al. 2021; Mayo-Wilson & Zollman 2021; Scheller et al. 2022), which aims to understand the spread of knowledge by considering individuals as agents sharing and receiving information through their interactions with the community (in contrast to isolated agents, in classical epistemology).

More concretely, an agent-based model in computational social epistemology relies on dynamic interactions between agents (in our case, the judges). Each agent starts with a set of opinions and updates them progressively by comparing them to the other agents’ opinions. By doing so, all agents in the community aggregate their judgments progressively. Such models can depict, for instance, how a general consensus or polarization can emerge in a group of individual agents (Douven 2019 p. 457). Of course, the way agents aggregate their judgments is highly model-dependent. There are several models used in computational epistemology: the Zollman (2007) model, and the Lehrer & Wagner (1981) model (which is itself a particular case of the DeGroot (1974) model), for instance, and their further improvements. In this paper, we will consider an improvement of the Hegselmann–Krause (HK) opinion dynamics model (Hegselmann & Krause 2002). This model is based on the DeGroot model with considering a time-dependant weight matrix instead of a time-constant one. The HK model (and its extensions) has already been widely studied in the literature (e.g., Olsson 2008; Douven & Kelp 2011; Douven & Wenmackers 2015; Gustafsson & Peterson 2012). We will explain our multivariate extension of the HK model in detail in the next section.

In our case, we will model three judges as agents who can try to persuade each other (instead of being isolated and submitting their responses to majority voting). After a long interaction, they can either agree on a common sentence (consensus of the agents) or be divided into two or more irreconcilable groups (polarization of the agents). In the latter case, the deliberation outcome is not clear and will be discussed. Some treatments of the doctrinal paradox have been investigated in the light of agent-based models (Wenmackers et al. 2012). These treatments assume that each agent (in this case, each judge) only has binary opinions (‘yes’ or ‘no’, 1 or 0). In general, however, we expect deliberative judgments to be more nuanced in general: e.g., a judge might be 60% certain that the defendant committed the action. For this reason, continuous-valued opinions instead of binary-valued ones will be considered in this paper. Furthermore, we will deal here with an epistemic community where each agent has a set of opinions and we will study how these sets interact. For interactions on systems of opinions and integrity constraints, see, for instance, Friedkin et al. (2016), Botan et al. (2017), Botan et al. (2019).

In the next section, we will explicitly construct a tailored agent-based model suited to represent the deliberative process. We will determine how often the doctrinal paradox occurs and compare these results with those of a majority voting procedure. This paper shows that the doctrinal paradox does occur. As we will see, its frequency will depend strongly on the size of the community, on the bound of confidence of the members of the community, and members’ commitment to the principle of reason.

Building the Model

This section introduces the model used in this article: a multivariate improvement of the Hegselmann–Krause (HK) opinion dynamic model. It also introduces the concept of truth flavor and broad/strict rationality that will be useful for the rest of the article.

The model implemented in this paper can be considered as a multivariate improvement of the Hegselmann–Krause (HK) opinion dynamic model (Hegselmann & Krause 2002). The latter pertains to the temporal evolution of opinions within a group of agents concerning one continuous variable, \(x\). The guiding idea behind this model is that an agent only interacts with those who have an opinion not too different from their own, as quantified by a variable called the bound of confidence. More formally, let’s consider a community of \(N\) agents and a single opinion variable, \(x\). An agent \(i\) possesses an opinion \(x_i(t) \in [0,1]\) concerning a given utterance at time \(t\). Agent \(i\) takes into account the opinion of another agent \(j\) if, and only if, the other agent’s opinion is within agent \(i\)’s bound of confidence \(\epsilon_i\). The set \(I(i,\vec{x}(t))\) (with \(\vec{x}(t)=(x_1(t),...,x_N(t))\)) of agents taken into account by agent \(i\) at time \(t\) is

| \[I(i,\vec{x}(t)) = \{1 \leq j \leq N \, |\quad |x_i(t)-x_j(t)|\leq \epsilon_i\} .\] | \[(1)\] |

| \[x_i(t+1) = \frac{1}{ \#(I(i, \vec{x}(t)))} \sum_{j\in I(i, \vec{x}(t))} x_j(t) ,\] | \[(2)\] |

Although this model is insightful, it only considers agents having an opinion about a single variable \(x\). To implement the doctrinal paradox properly, we have to consider a multivariate extension to the HK model (in our case, with three variables). Such an extension has already been considered in the literature (Bhattacharyya et al. 2013; Chazelle & Wang 2016; Douven & Hegselmann 2022; Nedić & Touri 2012), but was not applied to the doctrinal paradox. Besides considering many opinion variables, our model has to take into account variables at stake in the doctrinal paradox (the two premisses \(x\) and \(y\) and the conclusion \(z\))1 and they relations (if agents use the principle of reason, then \(z\) and \(x\wedge y\) have the same value).

This model can be improved regarding the definition of the bound of confidence. As it is currently formulated, if two agents \(i\) and \(j\) share very different views about \(x\) and \(y\) (meaning that \(|x_i-x_j|\) and \(|y_i-y_j|\) are bigger than \(\epsilon\)) but have pretty similar opinions about \(z\) (meaning that \(|z_i-z_j|\) is smaller than \(\epsilon\)), they update their opinions by averaging on their \(z\) opinions and leave their \(x\) and \(y\) opinions unchanged. In other words, there will be an epistemic interaction between the two agents even if their other opinions differ greatly. One may argue that the model lacks some realism in this regard.

More concretely, it means that if Alice has very different opinions from Bob on several subjects but merely agrees on a specific one, she will take the average of her opinion and Bob’s for this single subject. However, one might expect that Alice does not take into account Bob’s specific opinion even if it is close to hers. In Alice’s mind, Bob is clearly wrong, so she will not believe Bob in one specific utterance. Even worse, if she figures out that she shares a common opinion with Bob, she may perhaps think that there is something wrong with her opinion. We call this cognitive bias affinity bias: individuals are more prone to believe those who already share a huge number of identical opinions with them and to mistrust those who do not. We would like to implement this affinity bias into our model for the sake of realism and to quantify its impact on deliberative democracy. The bound of confidence has now to take into account not only the distance between two opinions (say \(x_{\text{Alice}}\) and \(x_{\text{Bob}}\)), but between whole sets \((x,y,z)\) of opinions of both Alice and Bob. If this distance is below a certain bound of confidence, then Alice will update her opinion.2 To encompass this feature, we improved our multivariate model.

The previous cognitive bias can be taken into account in our model if one considers a spherical confidence interval. That is, instead of Equation 1, we define it as follows:

| \[I(i,\vec{x}(t), \vec{y}(t), \vec{z}(t) ) = \{1 \leq j \leq N | \, d_{ij}(t) \leq \epsilon\}\] | \[(3)\] |

For now, the model simply implements communities of agents having three opinions (\(x\), \(y\) and \(z\)) evolving independently. However, the context we consider in this article is slightly different since the conclusion is logically constrained by the premises if the agent is rational. In this case, the agents always individually respect the principle of reason (i.e., \(z\) is a logical consequence of \(x\wedge y\), hence they have the same truth value). In classical logic, this conjunction states that \(z\) is true if and only if \(x\) and \(y\) are true. For any other choice of \(x\) and \(y\), \(z\) will be false. In our case, we have to define a continuous numerical function \(\textrm{AND}(\cdot,\cdot)\) that generalizes the discrete standard conjunction operator \(\wedge\). We are looking for a function which translate a logical operation (i.e., the conjunction) to a numerical operation (i.e., a function \(AND:[0,1]\times[0,1]\rightarrow [0,1]\)). We set up a list of some requirements that any \(\textrm{AND}\) operator should fulfill in a deliberative process. We expect this operator:

- to have a value between 0 and 1 for all \(x\) and \(y\) between 0 and 1 (by definition);

- to be consistent with the binary operator: AND(1,1) = 1 and AND(0,0) = AND(0,1) = AND(1,0) = 0. This requirement can be interpreted as: certainty about \(x\) and \(y\) values leads to certainty about \(z\). For instance, it might sound very strange to have a judge absolutely sure about both the fact that the defendant undertook the action and the legality of this action, and absolutely skeptical about the final culpability;

- to avoid certain verdicts under uncertainty of the premises: \(\mathrm{AND}(1,0.5)=\mathrm{AND}(0.5,1)=\mathrm{AND}(0.5,0.5)=0.5\). Were it not the case, a judge who is very skeptical about at least one of the first two propositions would be sure about the verdict, which is unfair. Thus, we do not allow arbitrary verdicts;

- \(\mathrm{AND}(0,y)=\mathrm{AND}(x,0)=0 \qquad \forall x,y \in [0;1]\). If a judge is certain that one of the two statements is false, they will judge the defendant as not guilty regardless of the other statement;

- to preserve truth flavor: AND(‘truly’,‘truly’) = ‘truly’ and AND(‘truly’,‘falsy’) = AND(‘falsy’,‘truly’) = AND(‘falsy’,‘falsy’) = ‘falsy’.

These five requirements not only seem to reflect a natural deliberative process but also give us some constraints on our choice of operator.

The logic we want to implement has been considered in the literature on fuzzy logic (for a review, see Priest 2008). We choose to adopt the definition of the fuzzy logic’s conjunction operator \(\textrm{AND}(x,y) \equiv \textrm{min}(x,y)\). This fuzzy option is in line with the existing literature about continuous-valued logic and aims to give some new contributions in this field for future improvement. Moreover, this definition is the continuous extension of the binary conjunction operator introduced in the first paragraphs of the introduction. The reader will find more information about the proprieties of this operator in the appendixes. We can now compute the \(z\) for a rational agent at each step: \(z(t)=\textrm{min}(x(t),y(t))\).

However, we should not take for granted that agents in a community are always aware of the consistency of their opinions. For instance, while watching or taking part in a political debate, a speaker can make the agent change their opinion on one isolated subject even if this opinion turns out to be in contradiction with other parts of their coherent political framework they had before the debate. Hence, a more realistic approach would be that the \(z\) value is determined by a mixture between the influence of other agent’s \(z\) values à la HK, and the conjunction of \(x\) with \(y\). We quantify the degree of mixture with the rationality coefficient \(\alpha \in [0,1]\). It relates to the agent’s propension to align with the principle of reason. Therefore, we propose the following update rule for the three opinions3:

| \[\begin{cases} x_i(t+1) = \frac{1}{ \#(I(i))} \sum_{j\in I(i)} x_j(t), \\ y_i(t+1) = \frac{1}{ \#(I(i))} \sum_{j\in I(i)} y_j(t), \\ z_i(t+1) = (1-\alpha) \frac{1}{ \#(I(i))} \sum_{j\in I(i)} z_j(t) + \alpha \cdot \textrm{min}(x(t+1),y(t+1)). \end{cases} \] | \[(4)\] |

If \(\alpha=0\), the agent will not pay attention as to whether their \(z\) is inconsistent with \(x\) and \(y\) and will only update \(z\) by averaging with the other agents. This extreme case is the irrational case. However, if \(\alpha=1\), the agent will disregard other’s agent \(z\) value and will replace their current \(z\) value with the conjuction of the current values of \(x\) and \(y\). This is the rational case.

Before going further, some clarifications are needed. Favoring interactions with other agent’s (\(\alpha=0\)) over the principle of reason (\(\alpha=1\)) is not a demonstration of irrationality, generally speaking. It can be epistemically virtuous to gain knowledge thanks to interactions with other peers. However, in line with the doctrinal paradox literature, I call this procedure irrational because the agent does not respect the principle of reason. At a given \(t\), an irrational agent (i.e., having \(\alpha=0\)) can still, by chance, experience an opinion state where \(z(t)=\textrm{min}(x(t),y(t))\). Although this agent is irrational, they have a rational opinion state at \(t\). Hence, we have to differentiate two rationality: on the one hand, the rationality in the aggregation procedure (i.e., \(\alpha=1\) and respecting the principle of reason for every \(t\)), and, on the other hand, the rationality in the opinion set \((x,y,z)\) where \(z(t)=\textrm{min}(x(t),y(t))\) at \(t\). The first implies the second but not conversely.

By adjusting \(\alpha\), we can study a lot of intermediate cases. In this article, we will study how the rationality coefficient (and other variable) impact the occurrence of the doctrinal paradox.

In conclusion, our model depends on several parameters:

- the initial values of \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) (\(z\) can be logically computed from \(x\) and \(y\) at \(t=0\) or not, see below) for each agent (continuous real values between 0 and 1, where 0 stands for ‘no’ and 1 for ‘yes’);

- the bound of confidence \(\epsilon\) (real value between 0 and \(\sqrt{3}\)) which has been chosen to be the same for all agents (for simplicity);

- the number of agents \(N\) (integer \(\geq\) 3);

- the rationality coefficient \(\alpha\).

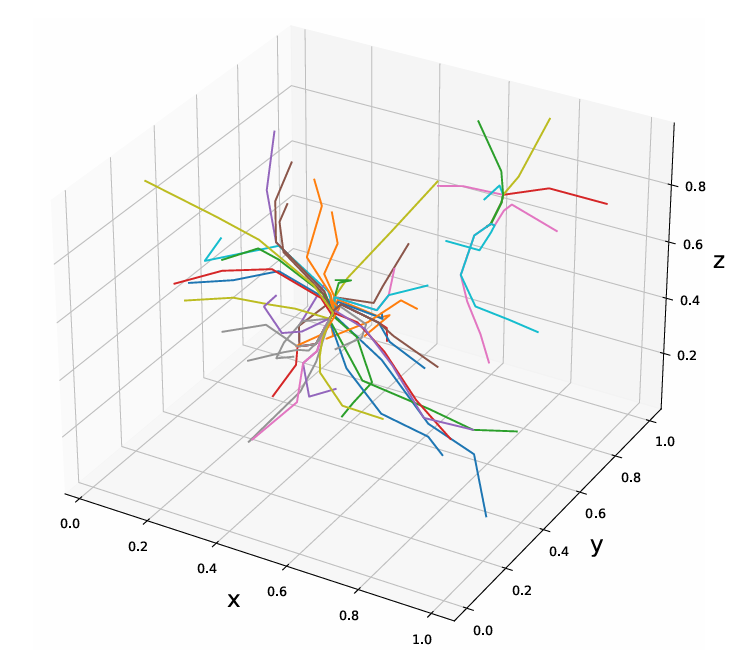

To be more concrete, we can represent an opinion in a 3D space. For a given time \(t\), the opinion values \((x,y,z)\) are simply the spatial coordinates of a point along each of the three axes. At each (discrete) time increment, agents update their opinions, and a new point is created. We define a world line as all the successive discrete positions of an agent in the 3D opinion space starting from \(t=0\) to \(t\rightarrow \infty\). These are represented in Figure 1 for 50 agents. Note that although these world lines are not continuous curves but discrete ones, we made all world lines continuous (by linear interpolation) to track their trajectory more easily. Note that all world lines have a finite length: opinions sets always stabilize for a value of \(t\) large enough (see Dittmer (2001) for the 1-dimensional case and Bhattacharyya et al. (2013) for the general \(n\)-dimensional case). Note also that the bound of confidence of an agent can be seen as a sphere in this 3D space centered on their opinion set. In the same way, agent \(i\) will trust agent \(j\) if, and only if, agent \(j\)’s opinions set \((x_j,y_j,z_j)\) is located inside a sphere of radius \(\epsilon\) centered on agent \(i\)’s opinion set.

In our example, the community’s agents converge into two polarized groups. Are the agents in these two groups rational? I.e., do their final opinion sets respect the principle of reason? One has to compare their final \(z\) value with those of the conjunction of the premises \(\textrm{AND}(x,y)\).

Our rationality definition is limited to the problem we want to address in this paper. Admittedly, other disciplines such as classical epistemology, game theory, or artificial intelligence might use another rationality criterion. We need a simple definition of rationality easily usable to determine whether the verdict of the three judges is rational or not. Our chosen definition seems to give a simple answer to this question and is in line with the argument of Pettit & Rabinowicz (2001). Nevertheless, this definition raises an issue. For instance, if an agent has the opinions \((0.1, 0.2,0.13)\), according to this definition of rationality, they will be considered irrational because \(\textrm{min}(0.1,0.2)=0.1\neq 0.13\). However, we would prefer to allow some leeway and consider this agent as rational despite the small deviation. To achieve this, we introduce the important concept of truth flavor, which can be ‘truly’ or ‘falsy’ and can be formally defined as:

For example, 0.56 and 0.8 have the same truth flavor (they are ‘truly’) but 0.2 and 0.6 do not (the latter is ‘truly’ whilst the former is ‘falsy’). In the example of the opinion set \((0.1, 0.2,0.13)\) is not strictly speaking rational, AND\((x,y)\) and \(z\) share the same truth flavor, namely ‘falsy’. Therefore, we could consider a broader and looser notion of rationality5, which we call broad rationality:

Unlike the classical setup of the doctrinal paradox, due to their interactions, the agent can adopt an irrational set of opinions after a few iterations even if they started with a rational one (if \(\alpha\neq 1\)). As we already mentioned, qualifying an agent as irrational, it does not mean that this agent did something epistemologically or procedurally wrong. After all, merging one’s opinions with those of other individuals can be seen as a rational strategy. We just mean that they are irrational in the sense that their own set of opinions \((x,y,z)\) is no longer consistent with the principle of reason. Before addressing the question of how often the community faces a doctrinal paradox, we deem it relevant to understand to which extent the individual agent can become irrational in our model. This is the aim of the next section.

Implementation

In this section, we will first explain how the multivariate extension of the HK model is implemented. We will study how often individual agent or the group can become irrational during and after the interaction process. We will divide this discussion in two parts: first for \(\alpha=0\), then for other values of \(\alpha\).

General principle

To understand whether a community contains an irrational agent, we introduce the concept of ‘irrational community’. We suppose that a community is irrational if at least one of its agents is broadly irrational. The irrationality of a community can be understood as a result of one or more agents’ irrationality.

In the 3D opinion space, it means that at least one agent7 is located in one of the four irrational regions of the opinion space (see later in Table 2). Of course, communities are never irrational if all their agents respect the principle of reason (i.e., \(\alpha=0\)).

In this article, we study the evolution of agents’s opinions and the logical consistency between these opinions in general. Hence, we do not focus on one specific community of \(N\) agents with fixed initial opinions. Instead, we explore all the possible scenarios, i.e., all the possible sets of initial opinions that \(N\) agents can have. To achieve this goal, we simulated, through a Monte Carlo sampling, many thousands of communities made of \(N\) agents with initial rational opinions (\(\alpha=0\)). Each of these randomized communities is called a universe. We use the noun universe to reflect the fact that the same initial community (i.e., with the same number of judges and the same bound of confidence) evolves differently if its members adopt different (rational) opinions from the start. By using this stochastic method, we aim to obtain a reliable value of the percentage of possible universes leading to irrationality in at least one of their subgroups at \(t \rightarrow \infty\). We define here a subgroup as a set of agents clustered in opinion space. In other words, a large number \(n\) of initial epistemic communities are randomly generated (typically, a few thousand) and left to evolve according to Equation 4. At the end of the interaction process, we divide the set of final universes into two groups: those for which all subgroups ended up broadly rational, and those for which at least one subgroup ended up broadly irrational. The frequency of rationality violation of the model is simply given by the ratio of the number of universes in the second group to the total number of simulated universes \(n\). In more Leibnizian terms, we can express this quantity as follows: if God had played dice, which percent of the time would he have created an irrational universe (at the end of the interacting process)?

One may expect each agent of a community to be rational at the very beginning of the interaction process. However, imposing a strict rationality requirement seems unrealistic: it would imply that each agent rates their \(z\) opinion exactly as \(\mathrm{min}(x,y)\). Instead, one could reasonably consider agents as broadly rational: they hold a coherence in the truth flavor of their initial set of utterances. We chose not to consider the (perfect) rational case because it would suppose that agents are perfectly rational in their opinions before any interaction, which seems unrealistic due to practical constraints.8

For these reasons, a starting sample of broadly rational agents is considered. \(N\) opinions \((x,y,z)\) are randomly regenerated in such a way that the opinion set is broadly rational. These allowed configurations are given in the truth table (Table 2). \(F(x)\), \(F(y)\) and \(F(z)\) stand for the truth flavor of propositions \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\). \(R(x,y,z)\) is the truth flavor of the utterance ‘The set of opinions \((x,y,z)\) is broadly rational’ (or, equivalently, ‘\(z=\text{AND}(x,y)\)’).

| \(F(x)\) | \(F(y)\) | \(F(z)\) | \(R(x,y,z)\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Falsy | Falsy | Falsy | Truly |

| Falsy | Falsy | Truly | Falsy |

| Falsy | Truly | Falsy | Truly |

| Falsy | Truly | Truly | Falsy |

| Truly | Falsy | Falsy | Truly |

| Truly | Falsy | Truly | Falsy |

| Truly | Truly | Falsy | Falsy |

| Truly | Truly | Truly | Truly |

\(R(x,y,z)\) is ‘truly’ in 4 cases out of 8, hence half of the time. Note that, by truth table analysis, one demonstrates that \(R(x,y,z) = \mathrm{XNOR}(\mathrm{AND}(x,y), z) = \mathrm{AND}(x,y) \leftrightarrow z\). Furthermore, this table suggests a fragmentation of the 3D opinion space into 8 cubes of dimension \(0.5\times 0.5 \times 0.5\). Four of them are rational regions (i.e., where \(R\) is ‘truly’ (\(>0.5\)), thus all the agents in these volumes are rational), and the other four are irrational regions. Note that the 3D space is homogeneous and isotropic: the Monte Carlo algorithm does not privilege any direction or region for \(n\) large enough, and the bound of confidence is the same in all three directions.

We chose to study three dependent variables:

- The ratio of irrational universe: the percentage of universes that contain at least one irrational agent at the end of the process.

- The ratio of irrational agents: the average percentage of irrational agents in all universes (rational or not) at the end of the process.

- The ratio of agents who expereinced irrationality: the average ratio of agents who adopted a broadly irrational opinion once or more along their world line. They can be rational or irrational at the end of the interaction process.

Results for \(\alpha=0\)

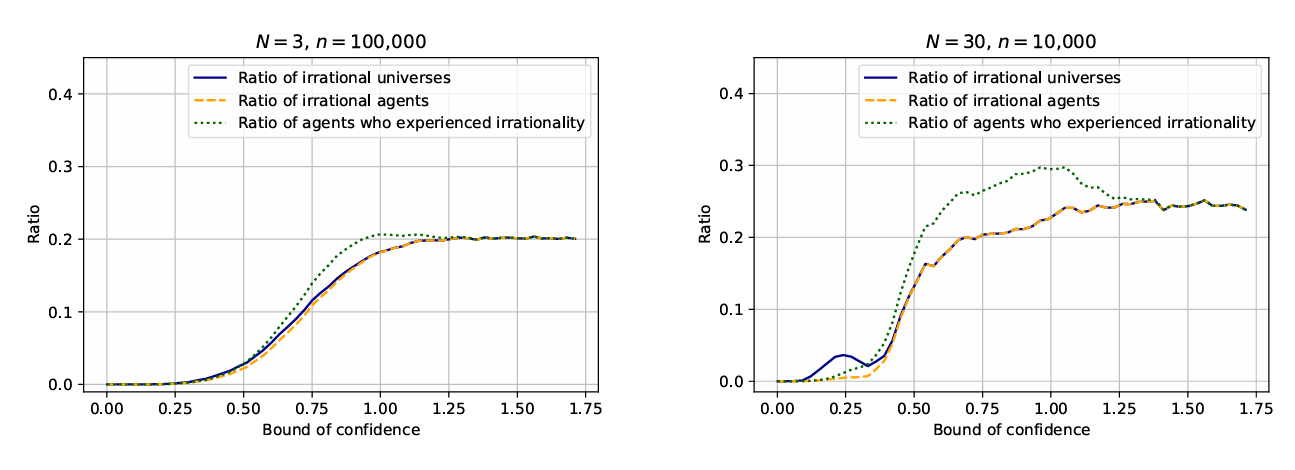

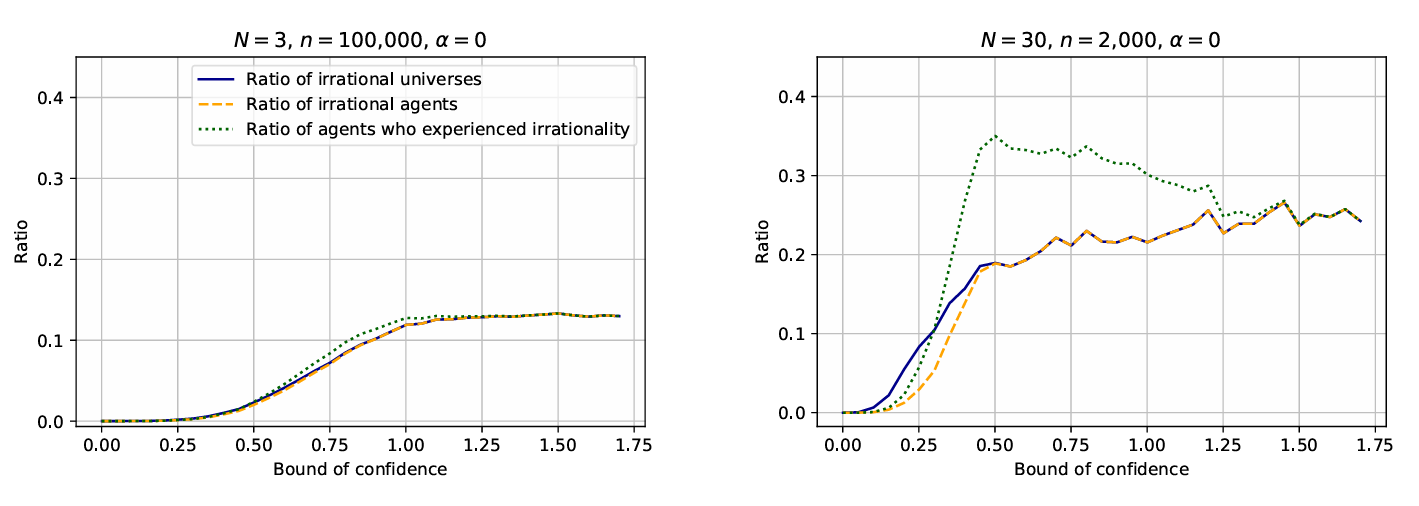

\(N\) opinions \((x,y,z)\) are randomly generated in rational regions of the opinion space (i.e., regions where the set of opinions \((x,y,z)\) is broadly rational) and left to evolve. They are free to evolve according to Equation 4. We observe whether some agents or all of the community become broadly irrational. The simulations have been performed in Python for \(N=3\) and \(N=30\) while varying the confidence interval \(\epsilon\) from 0 to 1 and letting the agents go through the whole iteration process (\(t \rightarrow \infty\)). To simplify the discussion, we considered that the agent does not respect the principle of reason when updating their opinion (i.e., \(\alpha=0\)). We stop the simulation once the agents have stabilized. This stabilization occurs when the difference between agent’s new opinions and the older ones is smaller than 0.001, for all agents. Stated differently, the code ends when \(\forall i (|x_i(t+1)-x_i(t)|<0.001) \& (|y_i(t+1)-y_i(t)|<0.001) \& (|z_i(t+1)-z_i(t)|<0.001)\). We run \(n\) simulations with the same parameters but with different initial (randomized) sets of opinions to reduce random noise. When averaging our results, we obtain Figure 2.

The blue solid curve represents the ratio of broadly irrational universes (i.e., those that contain at least one irrational agent at the end of the process). The behavior can be understood as follows. For small \(\epsilon\), each agent lies outside the bound of confidence of others, so the agents do not interact and stay stuck with their initial opinions. Because the initial distribution of opinions is broadly rational, the totality of the agent stays rational. By increasing the bound of confidence, the agents start to interact and form subgroups. Increasing \(\epsilon\) further, we see the same behavior as before but now at much lower ratios. For a large number of agents and a large value of \(\epsilon\), this ratio decreases to finally stabilize around \(0.25\). This value can be analytically explained (see the appendix). We notice as well that the shift between the small \(\epsilon\) and large \(\epsilon\) regimes is more abrupt when the number of agents is higher. This can be explained by the fact that, with more agents, the chance to have some agents bridging other agents and subgroups is higher. For extreme values of \(\epsilon\), the bound of confidence is so large that all the agents interact with each other and form, at the end of the process, only one single group (i.e., cluster at one point in the 3D opinion space).

The orange dashed curve depicts the average percentage of irrational agents in all universes (rational or not) at the end of the process. For small \(\epsilon\), the curve stays very close to 0. This can be understood with the same arguments as before. The curve stabilizes while merging with the blue solid one. This can be understood by the fact that, for a large value of \(\epsilon\), all the agents merge into one single group. Hence, each of the agents in the group has the same rational status as the group as a whole.

The green dotted curve presents the average ratio of agents who adopted a broadly irrational opinion once or more along their world line. For small \(\epsilon\), the agents are so narrow-minded that they do not experience any new truth flavor. Just after, the curve lies above the orange dashed one with a maximal gap value of 10%, meaning that 10% of the agents who started and ended in a rational state experienced an irrational state at least once in their past. However, for a bound of confidence very close to \(\sqrt{3}\), the two curves merge again. At this point, the agents are so open-minded that they include all other agents in their bound of confidence. Mathematically, Equation 1 is the same for all agents and Equation 4 as well. In this case, all agents converge (exactly) at \(t=2\).

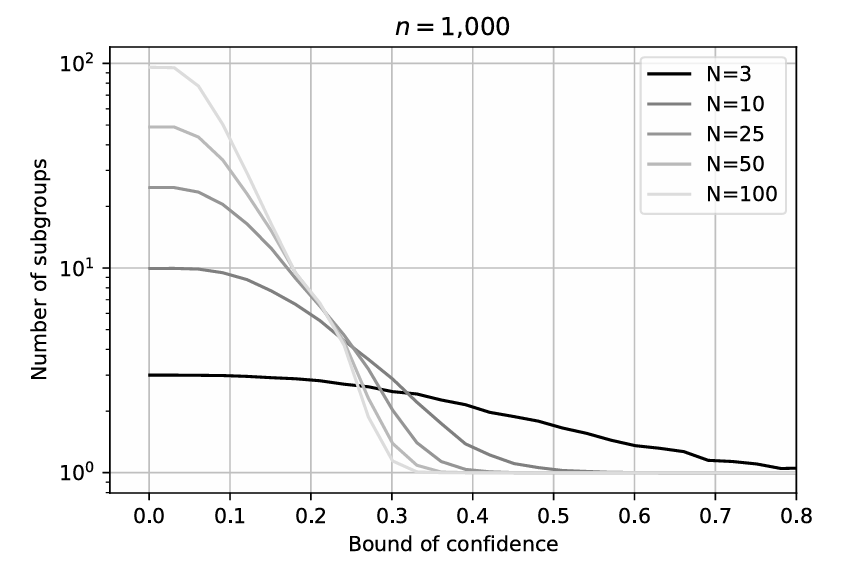

Figure 3 plots the average number of subgroups at the end of the opinion aggregation process for several values of \(N\). Notice the emergence of a consensus around \(\epsilon=0.3\), which is consistent with the results of Hegselmann & Krause (2002). Furthermore, the higher the number of agents, the easier the consensus is reached.

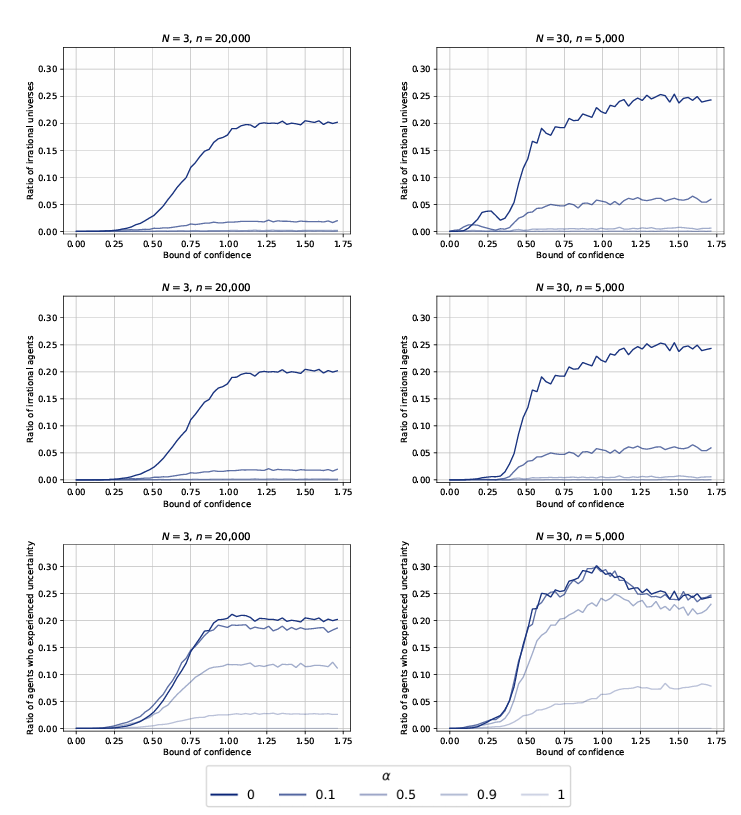

Results for other values of \(\alpha\)

The same simulation has been run to understand the influence of the rationality coefficient on the previous results. The generated graphs for five different values of \(\alpha\) are presented in Figure 4. We notice that both the ratio of irrational universe and the ratio of irrational agents rapidly drop. Stated differently, once agents partially accept the principle of reason (\(\alpha>0.1\)), they will not end with an irrational opinion set. However, they still experience irrationality at some step of the process (cf. the green dotted curve). This ratio of agents who experienced irrationality drops for high values of the rationality coefficient, although slower than the two other curves.

The decrease of the three curves is slower in more populous communities. In such communities, agents are more surrounded by other agents who can induce an irrational opinion set more easily.

This section offered a more intuitive understanding of the impact of the bound of confidence, the number of agents, and the rationality coefficient on individual and collective (ir)rationality. The next section evaluates how often our model leads to the doctrinal paradox. These results are compared to the case of majority voting. This is the core section of this article.

Comparison with Majority Voting

We will now evaluate whether our model (i.e., a deliberation process) leads the doctrinal paradox more or less often than a majority voting process. Before, we will first clarify what a majority voting process consists of in the case of continuous-valued opinions.

Binary majority voting and continuous majority voting

We come back to our initial inquiry. Does the agent-based model (i.e., a deliberative democracy deciding on the basis of consensus) lead less or more often to a discursive dilemma than a majority voting model? In the example of the court of law, we could invite the judges to vote at the end of the hearing and put their vote in a ballot. Then, they deliberate and interact (with the same dynamics as in the agent-based model). The final opinion of the resulting consensus is compared to the majority voting result performed before the interaction.

The first question that arises is: What is the procedure for a majority voting model when opinions are continuous rather than binary? We consider two ways of majority voting. For the first one, each judge rounds their initial opinion to the closest integer. For instance, if the judge has a degree of belief about an utterance of 60%, they will vote ‘Yes’. For 30%, they will vote ‘No’9. Such a rounding is not unusual: judges can not stay in a state of uncertainty and have to give a binary value to each proposition, so they may coarse-gain their opinion toward the closest binary option. We call this procedure the binary majority voting.

Another way of applying majority voting is by taking into account the uncertainty of the judges without reducing their opinions to 0 or 1. In this case, we simply compute the average over all the opinions, \(\bar{x}\),

| \[\bar{x} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^N x_i(0), \] | \[(5)\] |

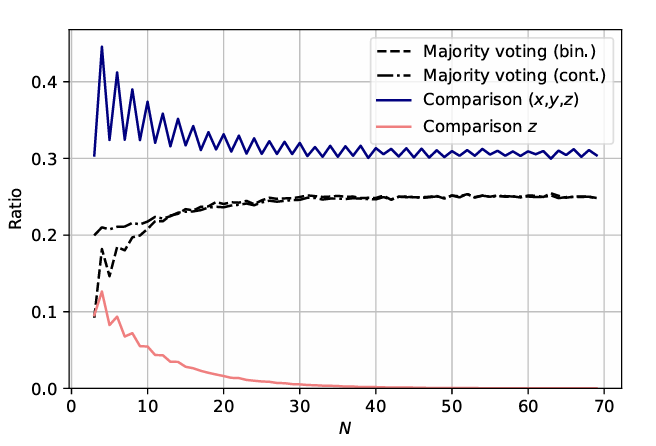

Before going further, let us assess the importance of this choice. In Figure 5, we simulate a large number of (broadly) rational universes and compare the outcomes between binary and continuous majority voting (before any interaction). The dashed (resp. dash-doted) curve represents the ratio of universes facing the discursive dilemma in the binary (resp. continuous) majority voting procedure in function of the number of judges, \(N\). This ratio is nothing but the frequency of the occurrence of doctrinal paradox in such a model. We notice that this frequency increases with \(N\) in both majority voting models. Stated differently, when there are more judges involved, the likelihood of a doctrinal paradox increases. Furthermore, it occurs as often in the binary as in the continuous majority voting once \(N\) is bigger than 15. However, even if both models produce the doctrinal paradox as often, it does not mean that, for each universe, the final verdict is the same in both procedures. The pink curve depicts how often the final verdict (i.e., the truth value of the proposition \(z\) ‘The defendant is guilty’) will differ between the two models. For instance, for the configuration of three judges, the two majority voting strategies will have different final verdicts 10% of the time. However, this discrepancy fades out for larger juries. In the same way, the blue curve compares the whole final set of opinions \((x,y,z)\) in the two majority votings. We notice that the set of opinions \((x,y,z)\) will differ 30% of the time for a large community. Note that all these frequencies will never depend on the value of the bound of confidence (\(\epsilon\)), because they are computed before any interaction takes place.

A second question arises: What happens if there are several irreconcilable polarized subgroups at the end of the interacting process (for small \(\epsilon\), for instance)? It is obvious that the court of law has to pronounce one, and only one, verdict. We can average over the remaining subgroups by making them vote and the weight of each vote is proportional to the number of agents in each group. In this case, we simply take the average of the opinions like in Equation 5. Note that in contrast with the vote processed in the majority voting model, the vote is here taken at the end of the interaction.

Results

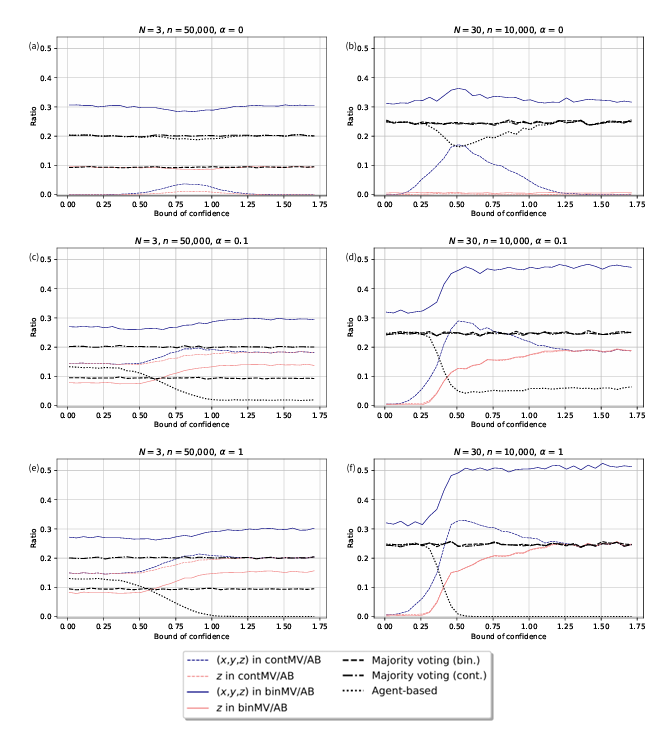

We simulated a large number of universes and compared for each initial configuration the outcomes with majority voting (binary and continuous) and agent-based interactions. In Figure 6, a huge number of broadly rational universes have been generated according to our agent-based model. The figures contain many data. There are presented according to the following convention:

- The black dotted curve represents the ratio of universes that end up with a doctrinal paradox in the agent-based model.

- Dashed and dash-dotted black lines depict the ratio of universes that end up with a doctrinal paradox for the binary and continuous majority voting, respectively. They are the same as those presented in Figure 5.

- The plain (resp. dotted) pink curve depicts the ratio of different verdicts \(z\) between the binary (resp. continuous) majority voting and the interaction model. This line is denoted by the legend z in binMV/AB (resp. z in contMV/AB).

- The plain (resp. dotted) blue curve depicts the ratio of different opinion sets (\(x,y,z\)) between the binary (resp. continuous) majority voting and the agent-based interaction. This line is denoted by the legend (x,y,z) in binMV/AB (resp. (x,y,z) in contMV/AB).

- Hence, the pink color always pertains to \(z\) and the blue one to \((x,y,z)\).

We considered different number of agents (\(N=3\) and \(30\)) and several rationality coefficients (\(\alpha=0\), \(0.1\) and \(1\)).10

Case \(\alpha=0\)

We first focus on plots (a) and (b) of Figure 6. In this configuration, the agents only update their opinion about \(z\) by averaging with their neighbors (cf. Equation 4 with \(\alpha=0\)). The doctrinal paradox occurs in binary majority voting 9% of the time for \(N=3\) judges and in 25% of the cases for \(N=30\) judges. In the scenario of continuous majority voting, the doctrinal paradox occurs more often: around 25% of the time in both cases (\(N=3\) and \(N=30\)). These results are consistent with the previous discussion about Figure 5.

We see that for a low number of judges (\(N=3\)), the binary majority voting leads to doctrinal paradox less often (in comparison with continuous majority voting and interaction procedure). Furthermore, we see that the final set of opinions \((x,y,z)\) will often differ. This discrepancy depends on the bound of confidence and can be explained as follows. The discrepancy disappears for high values of the bound of confidence because in this case, the interaction process amounts to an average of all the agents and the process ends after two iterations. Hence, the final opinion \(z\) of the group will \(z_\text{group} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^N z_i(1)= \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^N \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^N z_i(0)= \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^N z_i(0)\) (it goes the same for the final \(x\) and \(y\) opinions). For small values of the bound of confidence, the agents are isolated and do not interact. The algorithm stops after the first iteration. Hence, \(z_\text{group} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^N z_i(0)\). In these extreme cases, the opinions of every agent are averaged and the result is similar to the majority voting one (see Equation 5). Between these two extreme cases, the agents can interact and update their opinions in a less predictable way: for instance, a hill around \(\epsilon=0.8\) for \(N=3\) and around \(\epsilon=0.5\) for \(N=30\). These irregularities can be explained by the fact that for such value of the bound of confidence, agents are neither isolated forever nor behave as a herd instantly. Instead, they initiate collaborations with their small neighborhood, which gradually expand to the whole group. (Recall that in Figure 5, subgroups converge to one group from \(\epsilon=0.8\) for \(N=3\) and from \(\epsilon=0.5\) for \(N=30\)). Hence, slow deliberation increases the probability of opinion discrepancies with (continuous) majority voting. This argument does not apply to the binary majority voting, because the rounding disturbs the mean.

We see that for a high number of judges (\(N=30\)) the doctrinal paradox occurs as frequently in the continuous and binary majority voting process as in the interaction process. However, there is a decrease of 8% around \(\epsilon=0.5\) in the interaction process. This decrease can be explained by the same dynamics as exposed at the end of the last paragraph. Hence, a slow deliberation decreases the probability of a doctrinal paradox. We also notice that the final verdict, \(z\), is almost always identical in the three aggregation procedures.

Case \(\alpha\neq 0\)

We have only described the case \(\alpha=0\) so far. If we compare (a) and (b) with the four other plots (c), (d), (e), and (f), we notice that the behavior of all the curves is very sensitive once \(\alpha\) departs from 0, and changes very smoothly after. Many interesting phenomena appear.

First, whatever the value of \(N\) is, the occurrence of the doctrinal paradox in the interaction process decreases rapidly with the bound of confidence. It can even reach 0 for large values of \(\alpha\) and \(\epsilon\). In this specific region of the parameter space, agents rapidly converge toward the same \(x\) and \(y\) value since they have a large bound of confidence. The community behaves as a whole. Since each agents are mostly committed to the principle of reason (\(\alpha\) close to 1), they all end up with the same value of \(z\) since they all have the same values for \(x\) and \(y\). This explains why the group never breaks the principle of reason and does not cause any doctrinal paradox.

Second, suppose we have a look at large \(N\). In that case, we notice that the more the agents respect the principle of reason (i.e., the larger \(\alpha\) becomes), the more the deliberation outcome differs from majority voting (for a fixed value of the bound of confidence). For small values of \(\epsilon\), the three aggregation methods always align since the agents do not update their beliefs. For large bounds of confidence, an agent is highly likely to change their \(x\) and/or \(y\) value at each time increment. Consequently, since \(z\) directly depends on \(x\) and \(y\), its value will immediately change. It impacts the community’s final verdict.

Third, making the jury members interact will modify the final verdict in maximum 25% of the cases and the final set \((x,y,z)\) in 50%. Hence, the deliberation has a clear impact on the final jury’s choice. This impact is beneficial since it diminishes the chance of facing a doctrinal paradox, especially if agents are rational throughout the process and open-minded (i.e., willing to revise their opinion about \(x\) and \(y\) with the others).

In this section, we thoroughly compared the frequency of occurrence of the doctrinal in the interaction model with majority voting, both binary and continuous.

For the sake of completeness, we also study two variations of this model. In the first variation, we replaced the fixed bounds of confidence with random ones. The results are presented in Appendix C. The second variation considered a situation I which agents have limited time to decide. Hence, we impose a cut-off after a small number of iterations. We found that if we gradually lower the number of maximum iterations, the interaction curve merges more and more with the continuous majority voting curve. This is not surprising since agents have less and less time to interact and, at the extreme case, the verdict will be similar to a majority voting process.

Conclusion

This paper proposed a new approach to the doctrinal paradox by considering a deliberative decision process (that can be modelled by an agent-based model) instead of a majority-voting one. The model implemented can be considered a multivariate extension of the Hegselmann–Krause opinion dynamic model. Contrary to the HK model, this paper’s model considered three continuous variables \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\), where each of them is associated with one proposition of the doctrinal paradox (in the version of a court of law). Because real-world agents are expected to be more prone to take into account those who already share a huge amount of common opinions with them than those who do not, we implemented this feature in our model by considering the bounds of confidence as 3D spheres in the opinion space.

A quantitative comparison between (binary and continuous) majority-voting and agent-based generated final sentences has been performed. In each case, we compared the verdict given by a premise-driven approach and by a conclusion-driven approach. We applied this comparison to the three-member jury problem, as originally formulated by Pettit & Rabinowicz (2001), and we noticed that judges face the discursive dilemma more often when they use dialogue and debates to aggregate their judgments (20% of the time) than when they use binary majority voting (i.e., the judgment aggregation function considered by the original authors, 9% of the time). The final verdict \(z\) also differs in 9% of the cases between these two procedures. However, once the three jury members start taking into account the principle of reason (i.e., that \(z\) is the conjunction of \(x\) and \(y\)), the occurrence of the doctrinal paradox can vanish while the difference with the final verdict rises up to 15%.

In the extended context of deliberative democracy, one can expect the community to be more populous. As we saw, the doctrinal paradox for (binary or continuous) majority voting in these populous democracies is more frequent and stabilizes around 25%. If the members choose debates and discussions to aggregate their (\(x,y,z\)) opinion instead of majority voting, they still face the discursive dilemma but less often for certain values of the bound of confidence (i.e., depending on the intensity of their affinity bias). Surprisingly enough, the three procedures provide almost always the same verdict (although with different final values for \(x\) and \(y\)).

Things change once agents consider the principle of reason: they could always diminish or even avoid the discursive dilemma for a large bound of confidence. Their final verdict will differ with majority voting in a maximum of 25% of the cases. We extensively studied in Section 3 the corruption of agents’ rationality by their interactions with other agents (which never happens in majority voting). Against all odds, these interactions always reduce the frequency of the doctrinal paradox (compared with continuous majority voting). Our deliberation model is the only one out of the three that avoids the doctrinal paradox in a region of the parameters space. It means that a community can both respect the principle of reason at the individual level and at the group level. The conclusion-driven approach and the premise-driven approach merge and give the same outcomes. The group and its agents are always conversable. We can the save both the conversability of agents and the group if we impose the agents to be open-minded (i.e., having large bound of confidence regarding their opinion about the premises \(x\) and \(y\)).

It is worth being noticed that the doctrinal paradox is not something to be necessarily avoided. It just shows that a group can be (or fail to be) conversable in its own right, regardless of its members. As a consequence, it may happen that the group’s verdict can differ from those of the majority of the group’s members. Public debates (as implemented by our modified HK model) are an important feature of deliberative democracy and do not prevent society from facing the discursive dilemma, like for majority voting. In a premise-based approach, the group is a conversable agent: it can advance reasons for justifying its decisions. In a conclusion-based approach, in some cases (i.e., when the doctrinal paradox occurs), the group ceases to be a conversable agent. In this case, the group, as a whole, will appear to have inconsistent or arbitrary justification. Both in majority voting or interactive procedures, deliberative democracy will have to choose either to preserve the group as a whole or the majority of individuals.

Lastly, the present treatment is theoretical and relies on a set of hypotheses that can be contested. For instance, in the agent-based model, all agents are considered to have the same bounds of confidence. However, we expect a mix of different kinds of agents within a community: those who are radical (zero bound of confidence) and those who are very susceptible (large bound of confidence). Furthermore, it is not clear whether agents can become irrational during the interaction process without noticing it and rectifying their opinions accordingly or not. We also expect agents to modify the content of their opinions when communicating it in order to produce a more effective effect on the listener. All these questions open a manifold of possible extensions to our model. Maybe taking into account these new elements will point to a real difference between the final sentences generated by, on the one hand, the agent-based model and, on the other hand, a majority voting procedure.

Model Documentation

The code available at: https://www.comses.net/codebases/0d6de04d-0a06-4ce8-a78e-003ff0a520b9/releases/1.0.0/.Notes

- Here and in the rest of the text, we omitted indices \(i\) for ease of notation.↩︎

- We acknowledge that the article does not include any theory of mind and resulting strategical communication for the agents. For instance, some agent could exagerate some of their opinions when communicating them to strengthen their impact on the listener. It would be interesting for follow-up work to apply ideas from Rational Speech Act Theory, see for instance Vignero (2024), to make these agent-based models more realistic.↩︎

- Some authors also consider an hybrid form of opinion updating under the shape of \(x(t+1)=(1-\alpha) \frac{1}{ \#(I(i))} \sum_{j\in I(i)} x_j(t) + \alpha \cdot f(x,t,...)\). The function \(f\) can be the previous value of \(x\) (Chazelle & Wang 2016) or an attracting value coming from the world (Douven & Hegselmann 2022).↩︎

- In the context of a numerical simulation, due to approximation errors, we should consider an agent as strictly rational if, and only if, \(|z - \textrm{min}(x,y)| < \eta\), where \(\eta\) is a given numerical precision.↩︎

- This strategy also simplifies the numerical rounding errors.↩︎

- One can be dubious about considering rational an agent who has a set of opinions such as \((10^{-9}, 10^{-9}, 0.499999)\), for instance. However, what is at stake here is the coherence of \((x,y,z)\) in regard to their truth flavor and not their exact numerical value.↩︎

- One could have required that al least 50% of the agents have to be irrational to qualify a community ‘irrational’. In practice, this alternative definition does not change the results of Figure 2 and 4. This can be explained by the fact that agents often tend to behave as a herd. Either 0% or 100% of them end up irrational. However, some minor variations have been noticed for small values of bound of confidence in populous communities (data not shown).↩︎

- For the sake of exhaustivity, we have studied the purely rational case (see Appendix B). Interestingly enough, the outputs are qualitatively identical to those of the broadly rational case (although quantitatively slightly different), so our previous conclusions can be extended safely to the strictly rational case.↩︎

- One can argue that, to protect the presumption of innocence, only degrees of belief (concerning the guiltiness) above – say – 90% are reducible to ‘Yes’. We chose here to put this threesold at 50% to stay consistent with our previous notion of truth falvor.↩︎

- We omitted the case \(\alpha = 0.5\) because of its similarities with \(0.1\) and \(0\).↩︎

Appendix A

We present here an analytical explanation of the blue solid curve’s behavior in Figure 2. Initially (at \(t=0\)), all the agents are generated in the four rational regions of the 3D space and the four irrational ones are left empty. We can consider each of these rational regions as an attractor of the system and try to pull all the agents in its own region. However, the four attractors are competing and the final issue is not clear. In order to know the net attraction tendency of the system, we calculate the center of mass of this setup. Consider that each cubic region has its center of attraction (similar to the center of mass in physics) along the diagonal passing by the center \((0.5,0.5,0.5)\) and reaching the opposite vertex at \((\pm 1,\pm 1,\pm 1)\). For instance, the center of attraction’s location for the cube having \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) ‘truly’ (i.e. \(x,y,z >0.5\)) is \((0.5+a,0.5+a,0.5+a)\), where \(a\) is a constant between 0 and \(\sqrt{0.75}\). The center of attraction’s location of the system \((x,y,z)_{\textrm{CA}}\) is simply the average of the four rational regions’ ones:

| \[\begin{aligned} (x,y,z)_{\mathrm{CA}} =& \frac{1}{4} \big((0.5+a,0.5+a,0.5+a)\\ &+ (0.5+a,0.5-a,0.5-a)\\&+(0.5-a,0.5+a,0.5-a)\\&+(0.5-a,0.5-a,0.5-a) \big) \\ =& (0.5,0.5,0.5-a/2), \end{aligned}\] |

Appendix B

In this appendix, we consider an initial community of purely rational agents. The results are presented in Figure 7. There are only minor quantitative differences with Figure 2. For \(N=3\), the plateau is located around 0.13 and no longer at 0.2. For \(N=30\), the plateau is located at the same height (around 0.25). We also notice a larger increase in the ratio of agents who experienced uncertainty. These quantitative differences fade out when the rationality coefficient increases. Indeed, due to their progressive commitment to rationality, broadly rational agents become strictly rational after a few iterations. Hence, Figures 7 and 2 diverge less and less.

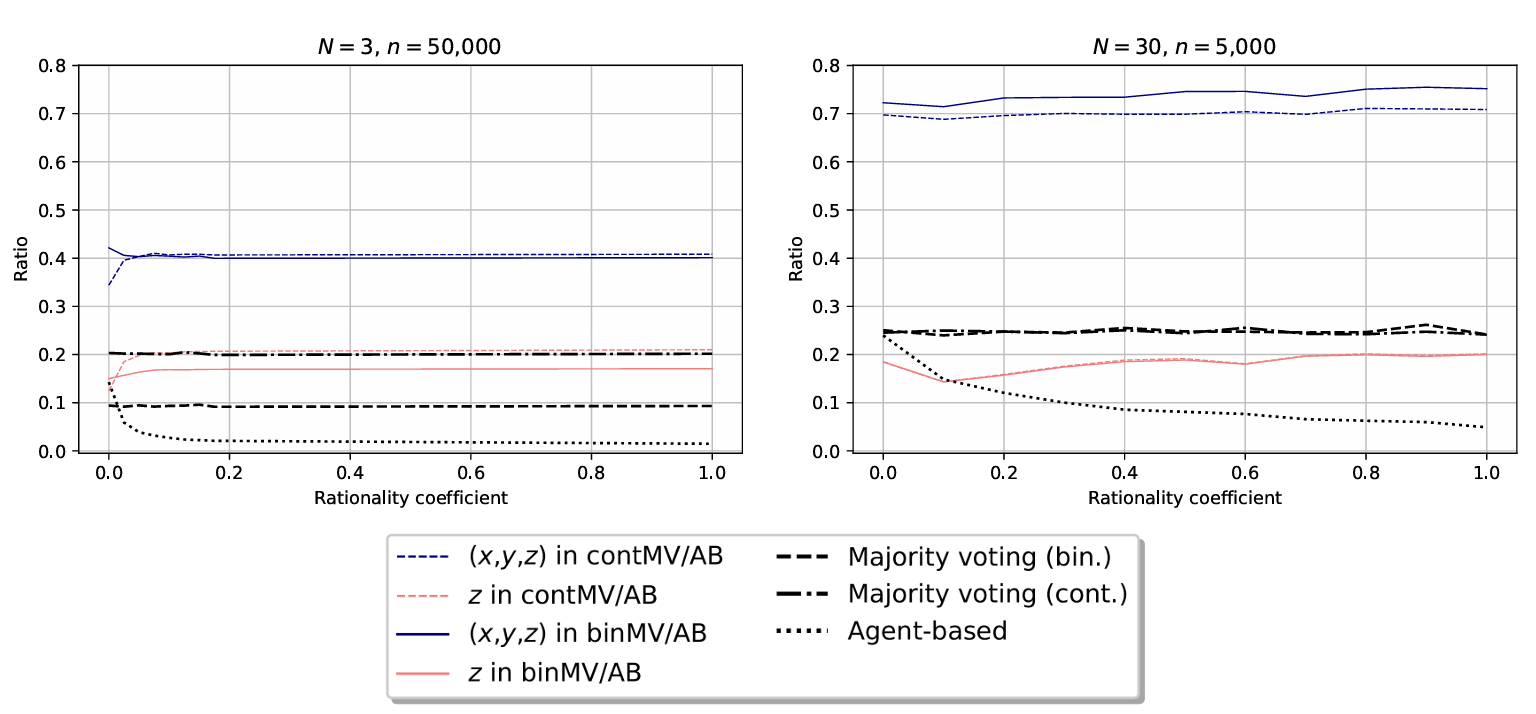

Appendix C

One can expect that, in general, agents do not have equal bounds of confidence. Some are more prone to change their opinion than others. In this section of the appendix, we consider a random bound of confidence for each agent. In this case, opinions updating is not reciprocal. One agent can update their opinions based on another agent, while the latter refuses to do so. We present here the impact on the frequency of the doctrinal paradox in Figure 8. In contrast with Figure 4, the horizontal axis denotes the rationality coefficient. We notice that in both graphs it is impossible to avoid the doctrinal paradox, even when agent are fully committed to the principle of reason. However, the interaction model still generates the doctrinal paradox less often than the binary and continuous majority voting. Moreover, the set of opinions \((x,y,z)\) will differ more than 70% of the time for \(N=30\).

References

AYDINONAT, N. E., Reijula, S., & Ylikoski, P. (2021). Argumentative landscapes: The function of models in social epistemology. Synthese, 199(1–2), 369–395. [doi:10.1007/s11229-020-02661-9]

BHATTACHARYYA, A., Braverman, M., Chazelle, B., & Nguyen, H. L. (2013). On the convergence of the Hegselmann-Krause system. Proceedings of the 4th conference on Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science. [doi:10.1145/2422436.2422446]

BOTAN, S., Grandi, U., & Perrussel, L. (2017). Propositionwise opinion diffusion with constraints. Proceedings of the 4th AAMAS Workshop on Exploring Beyond the Worst Case in Computational Social Choice (EXPLORE).

BOTAN, S., Grandi, U., & Perrussel, L. (2019). Multi-issue opinion diffusion under constraints. 18th International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (AAMAS 2019).

CHAZELLE, B., & Wang, C. (2016). Inertial Hegselmann-Krause systems. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 62(8), 3905–3913. [doi:10.1109/tac.2016.2644266]

DEGROOT, M. H. (1974). Reaching a consensus. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 69(345), 118–121. [doi:10.1080/01621459.1974.10480137]

DITTMER, J. C. (2001). Consensus formation under bounded confidence. Nonlinear Analysis: Theory, Methods & Applications, 47(7), 4615–4621. [doi:10.1016/s0362-546x(01)00574-0]

DOUVEN, I. (2019). Computational models in social epistemology. In The Routledge Handbook of Social Epistemology. London: Routledge. [doi:10.4324/9781315717937-45]

DOUVEN, I., & Hegselmann, R. (2022). Network effects in a bounded confidence model. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 94, 56–71. [doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2022.05.002]

DOUVEN, I., & Kelp, C. (2011). Truth approximation, social epistemology, and opinion dynamics. Erkenntnis, 75(2), 271–283. [doi:10.1007/s10670-011-9295-x]

DOUVEN, I., & Wenmackers, S. (2015). Inference to the best explanation versus Bayes’s rule in a social setting. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 68(2), 535–570. [doi:10.1093/bjps/axv025]

FRIEDKIN, N. E., Proskurnikov, A. V., Tempo, R., & Parsegov, S. E. (2016). Network science on belief system dynamics under logic constraints. Science, 354(6310), 321–326. [doi:10.1126/science.aag2624]

GUSTAFSSON, J. E., & Peterson, M. (2012). A computer simulation of the argument from disagreement. Synthese, 184(3), 387–405. [doi:10.1007/s11229-010-9822-3]

HEGSELMANN, R., & Krause, U. (2002). Opinion dynamics and bounded confidence models, analysis, and simulation. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 5(3), 2.

KORNHAUSER, L. A., & Sager, L. G. (1986). Unpacking the court. The Yale Law Journal, 96(1), 82–117. [doi:10.2307/796436]

KORNHAUSER, L. A., & Sager, L. G. (1993). The one and the many: Adjudication in collegial courts. California Law Review, 81, 1. [doi:10.2307/3480783]

LEHRER, K., & Wagner, C. (1981). Rational Consensus in Science and Society: A Philosophical and Mathematical Study. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

LIST, C. (2011). Group communication and the transformation of judgments: An impossibility result. Journal of Political Philosophy, 19(1), 1–27. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2010.00369.x]

MAYO-WILSON, C., & Zollman, K. J. (2021). The computational philosophy: Simulation as a core philosophical method. Synthese, 199, 3647–3673. [doi:10.1007/s11229-020-02950-3]

NEDIĆ, A., & Touri, B. (2012). Multi-dimensional Hegselmann-Krause dynamics. 012 51st IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC). [doi:10.1109/cdc.2012.6426417]

OLSSON, E. J. (2008). Knowledge, truth, and bullshit: Reflections on Frankfurt. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 32(1), 94–110. [doi:10.1111/j.1475-4975.2008.00167.x]

PETTIT, P., & Rabinowicz, W. (2001). Deliberative democracy and the discursive dilemma. Philosophical Issues, 11, 268–299. [doi:10.1111/j.1758-2237.2001.tb00047.x]

PRIEST, G. (2008). An Introduction to Non-Classical Logic: From If to Is. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SCHELLER, S., Merdes, C., & Hartmann, S. (2022). Computational modeling in philosophy: Introduction to a topical collection. Synthese, 200(2), 114. [doi:10.1007/s11229-022-03481-9]

VIGNERO, L. (2024). Updating on biased probabilistic testimony: Dealing with weasels through computational pragmatics. Erkenntnis, 89(2), 567–590. [doi:10.1007/s10670-022-00545-7]

WENMACKERS, S., Vanpoucke, D. E. P., & Douven, I. (2012). Probability of inconsistencies in theory revision. The European Physical Journal B, 85(1). [doi:10.1140/epjb/e2011-20617-8]

ZOLLMAN, K. J. (2007). The communication structure of epistemic communities. Philosophy of Science, 74(5), 574–587. [doi:10.1086/525605]