MIDAO: An Agent-Based Model to Analyze the Impact of the Diffusion of Arguments for Innovation Adoption

,

,

and

aUniversity of Toulouse, France; bUniversity of Montpellier, France

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (4) 4

<https://www.jasss.org/28/4/4.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5767

Received: 27-Oct-2022 Accepted: 23-Jul-2025 Published: 31-Oct-2025

Abstract

Numerous studies have highlighted the impact of interpersonal relationships in the dynamics of innovation adoption and diffusion. It is therefore natural that agent-based simulation is a commonly chosen approach for studying these dynamics, due to its ability to represent individual decisions and interactions between individuals. Some of these studies have focused specifically on the impact of social influences on the construction of an opinion on innovation. However, these works use a very abstract and simplified representation of the social influence process, which greatly limits the type of analysis that can be done, particularly on the diffusion of specific messages such as arguments defending or criticizing innovation. In this paper, we propose a model, MIDAO, based on the theory of planned behavior and formal argumentation, which aims to go further in this field by explicitly representing the arguments exchanged between agents. We have carried out a series of experiments demonstrating the importance of the messages introduced about the innovation, and the way in which they are disseminated, on innovation adoption.Introduction

In 1962, Everett Rogers, a sociologist and statistician, introduced the foundational concepts of the diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers 2003). He defined the diffusion of innovations as the process by which a new practice, idea, or product spreads within a society and proposed a five-stage representation of the adoption process: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation.

Building on this theory, numerous studies have sought to model the innovation diffusion process, aiming to understand how innovations spread and to predict their success in becoming established within a society. In particular, a widely recognized model that incorporates elements of Rogers’ work is the Bass model (Bass 1969). This model is designed to predict the peak of new adoptions. However, its explanatory power is limited, as it does not attempt to capture the decision-making processes of individual adopters. Instead, it focuses solely on the overall trajectory of the number of adopters over time. The model does not account for Rogers’ proposed stages of adoption, population heterogeneity, interactions between individuals, or the influence of dissemination efforts implemented by institutions.

Actually, analyzing these processes is challenging due to the complex dynamics involved, including human decision-making, interpersonal interactions, psychological factors, and the formation of social networks capable of disseminating information. Furthermore, it is now accepted that the decision-making process of individual adopters depends on socio-economic factors as well as behavioral and social control factors, and that any given behavior or adoption decision is the result of a cognitive and emotional process dependent on these factors. The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) seems to be the most relevant for this purpose at present.

To deepen the understanding of innovation diffusion processes, numerous studies, including Deffuant et al. (2005), have proposed using agent-based modeling to represent these dynamics. In such models, each agent represents an individual capable of influencing others in their adoption of the innovation. This approach is particularly valuable for examining the role of interpersonal interactions in the diffusion of innovations. However, these studies are often based on abstract models that simplify the processes of opinion formation and information exchange between individuals. Their virtue, as for most influential simulation models of collective behavior, lies in the capacity of reproducing an emergent behavior with minimal assumptions. These processes are typically represented by a numerical variable that evolves directly through agent interactions, offering limited insight into the cognitive mechanisms underlying an agent’s change in opinion. Consequently, the reasons behind an individual’s decision to adopt or reject an innovation remain unexplained.

To address this limitation, recent research in opinion dynamics, such as Stefanelli & Seidl (2017), Butler et al. (2019b), Taillandier et al. (2019), has introduced the use of formal argumentation (Besnard & Hunter 2008a; Dung 1995) to explicitly represent the exchange of arguments between agents. This approach offers a more realistic depiction of the processes that drive individuals to change their opinions. It also enables tracking the dissemination of specific messages, highlighting how the structure of a social network influences both the spread of messages and the diffusion of opinions.

In this paper, we present a new model for innovation diffusion, called MIDAO (Model of Innovation Diffusion with Argumentative Opinion), which builds on prior work in formal argumentation, particularly the model proposed by Taillandier et al. (2019). However, MIDAO introduces several key differences: it not only focuses on opinion formation but also incorporates a comprehensive innovation adoption process grounded in the framework of Rogers (2003). Additionally, it adopts the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) as a broader conceptual framework, allowing the model to account for both the influence of arguments on opinion formation and the impact of social opinions on individual decisions. The model was implemented using the GAMA platform (Taillandier, Gaudou, et al. 2019), which includes a dedicated plugin for argumentation (Taillandier et al. 2019).

The paper is organized as follows: The first section reviews existing studies, with a particular emphasis on those exploring the influence of interpersonal relationships on the innovation diffusion process. In the second section, we introduce the MIDAO model, detailing its structure using the ODD protocol (Grimm et al. 2020). This is followed by a presentation of simulation experiments conducted. Finally, we conclude by summarizing the findings and exploring potential future directions for this research.

Previous Works

Agent-based simulation has been extensively applied in the field of innovation diffusion (Kiesling et al. 2012). Zhang & Vorobeychik (2019) provided a critical review of such models, categorizing them based on how they represent the decision to adopt an innovation. Among these categories, cognitive agent models stand out as particularly relevant to our focus, as they explicitly aim to represent the cognitive and psychological mechanisms by which individuals influence each other.

A notable example within this category is the model proposed by Deffuant et al. (2005), rooted in opinion dynamics research, particularly the relative agreement model (Deffuant et al. 2002). This model draws from Rogers’ adoption stages but emphasizes the concept of opinion regarding an innovation. Opinions and uncertainties are numerically represented and evolve through interpersonal interactions (Deffuant et al. 2000; Hegselmann et al. 2002): when two agents meet, they adjust their opinions, provided their differences are not too large. This model is well-suited to studying social influence in innovation diffusion. However, it does not capture the internal motivations underlying an agent’s opinion change. Since opinions are encapsulated in a single numerical value, the reasons for these changes remain unexplored.

While agent-based modeling effectively captures social dynamics among heterogeneous individuals, these dynamics are both shaped by and influence agents’ decision-making processes. In innovation diffusion, agents require a cognitive framework to make adoption decisions. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen 1991) provides a particularly apt framework that has been widely applied in this domain. TPB describes the psychological process leading an individual to engage in a specific behavior, focusing on the concept of intention, i.e. the motivation to perform a behavior, reflecting the individual’s willingness to act.

Intention in TPB is derived from three factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (PBC). Attitude reflects the individual’s evaluation of the behavior, subjective norms represent social pressure to adopt it or not, and PBC captures the perceived ability to perform the behavior considering skills, time, and resources. As Scalco et al. (2018) note, TPB is highly suited to agent-based modeling, offering a parsimonious yet comprehensive way to incorporate individual, social, and external factors based on solid psychological foundations.

To date, there are numerous applications of TPB agent models focusing on environmentally friendly farming practices: Bourceret et al. (2022), (2023), (2024) for water quality management or agricultural phytosanitary practices; Huber et al. (2024) for sustainable farming practices; Feng & Wang (2024) for irrigation-induced landslides. But in most of these studies, interactions between agents are not considered as direct exchanges but as the result of social norms. Other studies, such as Borges et al. (2014), explore factors influencing Brazilian farmers’ decisions about adopting agricultural innovations, while Yazdanpanah (2014) applies TPB to assess the impact of environmental policies in Iran. Similarly, Kaufmann et al. (2009) models Baltic farmers’ adoption of organic practices using TPB.

Although TPB effectively identifies major factors driving the adoption of new behaviors (or innovations), it does not elucidate how an agent’s attitude, social norms, or PBC are formed. Even if certain models tend to extend the conceptual framework by proposing an extended TPB model (Tama et al. 2021) or a socio-psychological model combining a TPD model and a social capital model (Castillo et al. 2021) where the attitude is conditioned by the agent’s social network which functions as a platform for interaction and communication with a circle of friends and peers. Moreover, interactions with others are limited to indirect influences via social norms. This raises critical questions, central to this research, about how these factors evolve through interpersonal relationships and how they shape an individual’s intention to adopt an innovation.

A particularly promising domain for addressing these questions is formal argumentation. This field deals with scenarios where information is contradictory, often arising from multiple sources or perspectives with varying priorities. It models reasoning as the construction and evaluation of interacting arguments. Initially formalized in philosophy and computer science (Rescher 1997), formal argumentation has since been applied in areas such as non-monotonic reasoning (Dung 1995), decision-making (Thomopoulos 2018), and negotiation (Kraus et al. 1998). Early applications in computer science focused on legal reasoning (Prakken & Sartor 2015), but more recent studies highlight its relevance to social systems and controversies (Dupuis de Tarlé 2024; Thomopoulos 2018), food supply chains (Chaib et al. 2022), and environmentally friendly farming practices (Thomopoulos et al. 2018).

Prakken (2018) distinguishes between two main perspectives in argumentation: argumentation as inference (reasoning from incomplete or conflicting data) and argumentation as dialogue (structured verbal exchange). Within the first family, a pivotal contribution is the work of Dung (1995), which introduced abstract argumentation frameworks in which arguments are represented as nodes in a directed graph and attacks as edges between them. This formalism has been extended in many directions (see Besnard & Hunter (2008a) for an overview). Building on this foundation, several studies have proposed enriching the framework by adding attributes to arguments, allowing for more detailed content analysis (Bourguet et al. 2013; Thomopoulos 2018; Thomopoulos et al. 2021; Yun et al. 2018). Another branch of work focuses on logical models (Besnard & Hunter 2008b), where arguments are formalized as structured propositions supported by evidence, particularly in the context of applied decision-making (Tamani et al. 2015; Thomopoulos et al. 2015).

Carrera and Iglesias’ 2015 systematic review (Carrera & Iglesias 2015) on argumentation in multi-agent systems highlights Dung’s framework and Rahwan et al.’s Argumentation-Based Negotiation model (Rahwan et al. 2003) as the most widely used. Several agent-based models adopt Dung’s framework for opinion dynamics. For example, Gabbriellini et al. (2013), Gabbriellini & Torroni (2014) use a shared argument set among agents, exchanging attacks during dialogues. However, these models assume a common argument set, limiting individual agent variability.

Similarly, Butler et al. (2019b) combines Dung’s framework with interpersonal influence processes (Deffuant et al. 2000) to model collective decision-making. Agents deliberate in groups, exchanging arguments and adjusting their opinions. Extensions by Butler et al. (2019a) and Butler et al. (2019b) introduce argumentative epistemic vigilance, allowing agents to reject arguments based on inconsistencies between messages and sources.

Lastly, Taillandier et al. (2019) and Taillandier et al. (2021) propose a model where each agent maintains its argument graph, constructed using Dung’s framework and extended with evaluative attributes. Opinions are derived by identifying coherent argument subsets and evaluating them based on individual preferences. This approach effectively integrates agent heterogeneity and provides a comprehensive process for opinion formation and evolution.

To conclude, agent-based simulation has been identified as a particularly suitable and popular approach for studying innovation diffusion. While many existing agent-based models draw on Rogers’ work to describe the adoption process, they often adopt a highly abstract view of adoption and fail to articulate the specific reasons driving an agent to change their opinion and ultimately adopt the innovation. To delve deeper into the decision-making process, a widely used theoretical framework is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which accounts for the key factors that shape the intention to adopt: the agent’s attitude toward the innovation, perceived social norms, and the perceived difficulty of adoption and use.

Most studies employing the TPB framework calculate these factors using ad hoc and overly simplified methods. However, in the field of opinion dynamics simulation, some works propose using formal argumentation to calculate agents’ opinions—corresponding to attitudes in the TPB framework. Formal argumentation offers a way to explicitly represent the reasons behind changes in opinion and provides a more detailed representation of interpersonal interactions, which are central to the innovation diffusion process. However, to our knowledge, formal argumentation has never been applied within the context of innovation diffusion in conjunction with Rogers’ framework nor the Theory of Planned Behavior.

The work presented in this paper aims to advance the understanding of the innovation adoption process by proposing a model, MIDAO, that integrates these three approaches. It draws on Rogers’ work to describe the overall adoption process, employs the Theory of Planned Behavior to define the intention to adopt, and leverages formal argumentation to articulate how agents form personal opinions about the innovation (attitude) and how they persuade others of its value. MIDAO is a generic model in the sense that it can be applied to various innovations and populations without being tied to a specific context. However, it does not aim to encompass all the socio-cognitive processes involved in the diffusion of innovation. Instead, it focuses primarily on interpersonal interactions, particularly the exchange of arguments between individuals.

MIDAO Model

General architecture of MIDAO agents

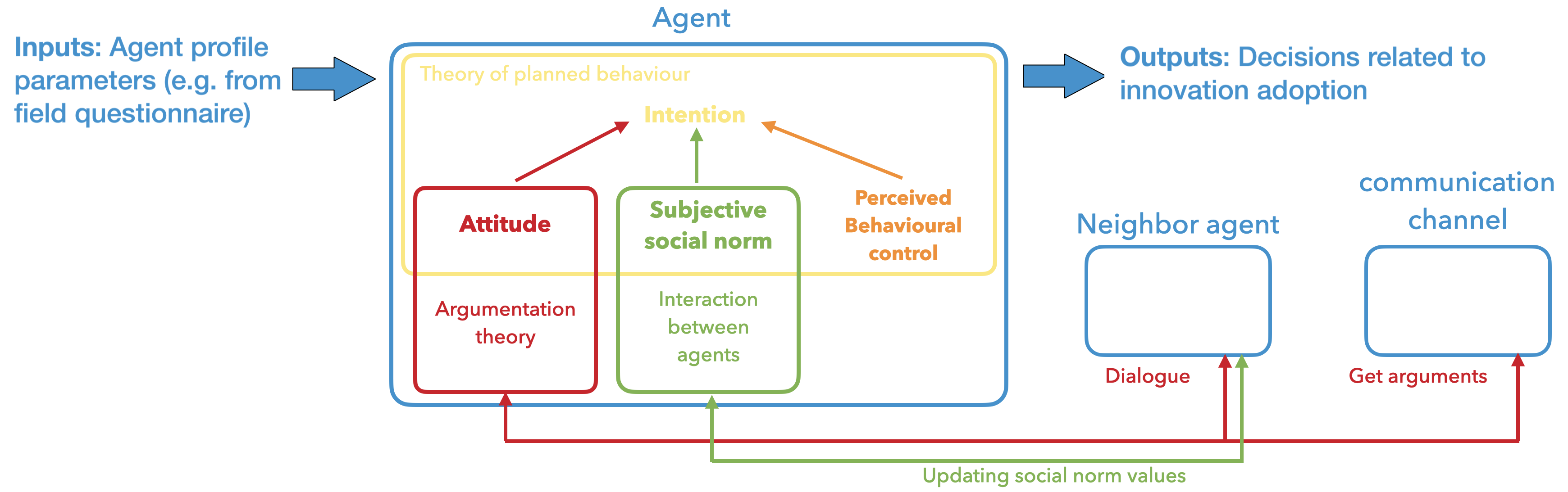

Figure 1 presents the general architecture of MIDAO agents. Each agent is characterized by a psychological profile defined through a set of parameters, which may be derived, for example, from stakeholder questionnaires. Based on this profile, the agent is expected to generate decisions regarding the adoption of the innovation. This architecture draws upon the adoption stages proposed by Rogers (2003), which shape the agent’s behavior toward the innovation—such as seeking information or engaging in dialogue with other agents. The progression through these stages is largely influenced by the agent’s intention to adopt the innovation. The adoption intention is defined using the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen 1991), which is based on three concepts: attitude, social norm, and perceived behavioral control. The attitude, representing how an agent evaluates the innovation, is determined by the agent’s knowledge of the innovation. MIDAO utilizes Dung’s argumentation framework, specifically the acceptability semantics, to assess the agent’s attitude toward the innovation. Agents can initiate dialogues with other agents to exchange arguments and seek new arguments through the communication channel. Through these interactions, agents gain a better understanding of others’ opinions on the innovation (adoption intention), which, in turn, influences their own opinion.

The following sections provide an in-depth explanation of the theoretical foundations of MIDAO: the Theory of Planned Behavior, Dung’s argumentation framework, and acceptability semantics. The subsequent section offers a comprehensive description of the model, following the ODD protocol (Grimm et al. 2020).

Theoretical background

The theory of planned behavior

While the Theory of Planned Behavior offers a clear framework for constructing the decision-making component of agents, it provides a qualitative model and cannot be directly applied in computational settings. To adapt this theory to agent-based modeling, Kaufmann et al. (2009) proposes an equation that calculates the intention to adopt a behavior based on the values of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) for a given agent. In our model, we use the same equation to compute the adoption intention for each agent:

| \[ I_i = w_i^a a_i + w_i^s s_i + w_i^p p_i\] | \[(1)\] |

The argumentation framework

The argumentation framework was selected for our model because it offers various semantics to compute values based on arguments. In our model, arguments represent pieces of information about the innovation that agents can understand and share. Various formalisms exist for representing arguments and their relationships. While many studies treat arguments as abstract entities without descriptive details, other research has extended this concept by integrating attributes into arguments (Bourguet et al. 2013; Taillandier et al. 2019; Thomopoulos et al. 2018). In this work, we adopt the representation proposed by Taillandier et al. (2019), where the data composing the argument serves as support for evaluating knowledge. This approach allows for both pro and con arguments, accordingly to the decision-oriented framework of Amgoud & Prade (2009). Thus, an argument \(a\) is defined as a tuple \((I_a, O_a, T_a, S_a, C_a, Ts_a)\):

- \(I_a\): the identifier of the argument

- \(O_a\): The option related to the argument

- \(T_a\): the type of argument (pro: +, con: -)

- \(S_a\): the proposition supported by the argument

- \(C_a\): the criteria (themes) associated with the argument

- \(Ts_a\): the type of the argument’s source

Arguments are connected through the concept of attack, which occurs when one argument opposes or challenges another. For further details on attacks, refer to Yun et al. (2018).

The advantage of this formalization is that it allows for a straightforward representation of arguments with clearly defined polarity (pro or con) that can be easily discussed with stakeholders to reach consensus on lists of arguments, as illustrated in Taillandier et al. (2021) about the transition to vegetarian diets.

Acceptability semantics

The structuring of arguments and attacks in the form of a graph allows for the analysis of coherent argument subsets and the determination of each argument’s acceptability. In this context, the work of Amgoud et al. (2017) introduces new semantics for computing acceptability in Dung’s framework for argumentation graphs with weighted arguments.

This is the case in MIDAO, which evaluates the strength of an argument for an agent based on the type of sources and the themes it addresses, as proposed by Taillandier et al. (2019). The semantics from Amgoud et al. (2017) are then applied to compute the acceptability of each argument, a value that combines the argument’s strength with its position in the argumentation graph’s topology. Specifically, we employ the Weighted Max-Based Semantics, which reduces the strength of an argument based on the strongest argument attacking it. More precisely, this semantics prioritizes the quality of attackers over their quantity by focusing on the strength of individual attacks rather than their number. It relies on a scoring function that operates through a multi-step process. Initially, each argument is assigned a score equal to its basic strength. At each subsequent step, the score is updated based on both the argument’s basic strength and the score of its strongest attacker from the previous step. It is worth noting that other types of semantics could have been considered. In Section 4.10, we analyze the impact of the three semantics proposed by Amgoud et al. (2017) on the model outputs.

ODD MIDAO presentation

Overview

Purpose and patterns. MIDAO (Model of Innovation Diffusion with Argumentative Opinion) is designed to simulate the diffusion of innovations by explicitly modeling the exchange of arguments between agents. It is based on the five key factors identified by Rogers (2003) as essential for the diffusion of innovation: the innovation itself, the adopters, the communication channels, time, and the social system.

The model is evaluated based on its ability to reproduce a normal distribution for the adoption process over time. As highlighted by several studies, the classic distribution of adopters typically follows an S-shaped curve over time (Bass 1969; Ghanbarnejad et al. 2014; Rogers 2003).

Entities, state variable and scales. MIDAO is composed of two types of agents: Individual agents, which represent potential adopters, and CommunicationChannel agents, which represent methods of information collection (such as the Internet or TV). The list of variables for Individual agents and CommunicationChannel agents are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

| State variable | Data Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(C_i\) | list of floats - static | Importance of each criterion |

| \(SN_i\) | list of Individual agents - static | Relatives, i.e., social network |

| \(Ts_i\) | list of floats - static | Trust for each source type |

| \(CC_i\) | list of floats - static | Probability of use for obtaining information from each CommunicationChannel agent |

| \(PU_i\) | float - static | Probability of obtaining new arguments through the use of the innovation |

| \(IF_i\) | float - static | Influence factor of the agent |

| \(w_i^a\) | float - static | Weight of attitude |

| \(w_i^s\) | float - static | Weight of social norm |

| \(w_i^p\) | float - static | Weight of PBC (Perceived Behavioral Control) |

| \(State_i\) | state - dynamic | Current step in the decision-making process |

| \(Arg_i\) | graph of arguments - dynamic | Known arguments and their associated lifespan |

| \(a_i\) | float - dynamic | Value of attitude |

| \(s_i\) | float - dynamic | Value of social norm |

| \(p_i\) | float - dynamic | Value of PBC |

| \(I_i\) | float - dynamic | Value of Intention |

| \(u_i^I\) | float - dynamic | Uncertainty regarding the intention |

| State variable | Data Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(Type_k\) | string - static | Type of communication channel |

| \(Args_k\) | list of arguments - static | List of arguments that can be retrieved from the communication channel |

| \(Ind_k\) | list of Individual agents - static | List of individual agents that can be impacted by the channel |

The model does not explicitly represent space (although the social network \(SN_i\) can be generated using spatial properties), and time is generally treated as abstract, though it can be specified based on the specific application case.

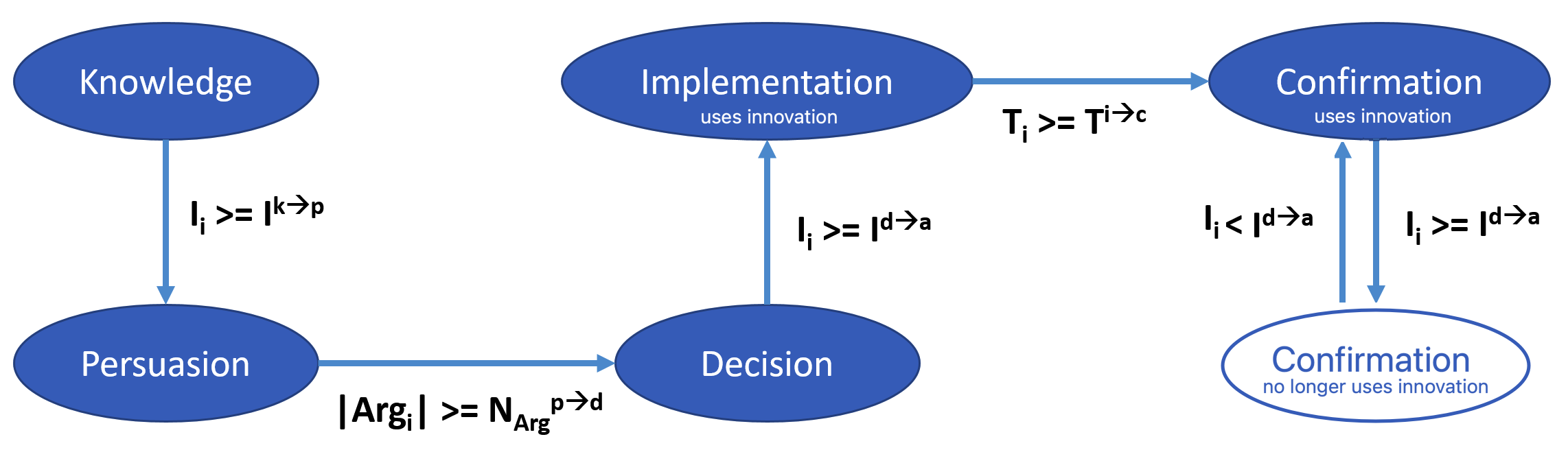

Process overview and scheduling. The behavior evolution of Individual agents regarding the innovation follows Rogers’ five stages and is influenced by three factors: the agents’ knowledge (i.e., the number of arguments they know about the innovation), their intention to adopt, and time. In MIDAO, this evolution is modeled using a finite state automaton that incorporates the five decision steps proposed by Rogers (see Figure 2). At the beginning of the simulation, the Individual agents are in the ‘Knowledge’ state: they are exposed to the innovation but have no interest in it and do not seek further information. If their intention to adopt surpasses a threshold \(I^{k \rightarrow p}\), they will enter the ‘Persuasion’ state, where they actively seek information to form an opinion. They will exchange arguments with others in their social network and search for information from communication channels. Once the agent has gathered enough information, i.e. when the number of arguments exceeds a threshold \(N_{Arg}^{p \rightarrow d}\), it enters the ‘Decision’ state, where it will decide whether to adopt the innovation. If the agent’s intention to adopt surpasses the threshold \(I^{d \rightarrow a}\), it will enter the ‘Implementation’ state and adopt the innovation. During the ‘Decision’ state, the agent will continue to search for information (by interacting with other agents or seeking out communication channels). After a certain period (when the time since adoption exceeds a threshold \(T^{i \rightarrow c}\)), the agent transitions to the ‘Confirmation’ state. In this state, the agent will continue to use the innovation if its intention to adopt remains above the adoption threshold \(I^{d \rightarrow a}\). Otherwise, the agent will stop using the innovation but may reconsider and reuse it again if its intention rises above the threshold \(I^{d \rightarrow a}\). In both the ‘Implementation’ and ‘Confirmation’ states, the agent no longer actively seeks information from communication channels but continues to engage in discussions with other agents about the innovation. Additionally, during the ‘Implementation’ state and the ‘Confirmation’ state with continued innovation usage, the agent can acquire new information (i.e., new arguments) through its experience with the innovation. Specifically, at each step, an Individual agent has a probability \(PU_{i}\) of uncovering an argument through the usage of the innovation. Indeed, by using the innovation, the agent can assess its benefits and drawbacks. The argument is randomly chosen from the set of arguments associated with the innovation’s usage.

Regarding information retrieval from communication channels, at each step of the search, an Individual agent \(i\), has, for each communication channel \(k\), a probability \(CC_i(k)\) of discovering an argument from it. The argument is randomly selected from the set of arguments available in the communication channel, \(Args_k\). As for interactions between Individual agents, an agent \(i\) wishing to exchange information with others has, at each time step, a probability \(P_i^{exchange}\) of actually interacting with another agent. \(P_i^{exchange}\) is calculated as follows:

| \[ P_i^{exchange} = \alpha_{exchange} \times \frac{|SN_i|}{\sum_{k \in Ind}{|SN_k|}}\] | \[(2)\] |

with \(Ind\) representing the set of Individual agents, and \(\alpha_{exchange}\) being a global parameter that defines the frequency of exchanges between Individual agents.

The assumption behind this probability is that an agent with a larger social network will have more interactions than an agent with a smaller social network. The Individual agent with whom the agent engages in the argumentative exchange is selected randomly from its social network.

Each time an Individual agent interacts with another agent or a media source, or forgets an argument, it updates its intention to adopt. The intention calculation, based on Equation 1, directly depends on the agent’s attitude, social norm, and perceived behavioral control (PBC). The attitude is derived from the arguments the agent knows, using the Weighted Max-Based Acceptability Semantics (Amgoud et al. 2017). The social norm evolves over time as the agent interacts with others, gradually aligning with that of the interacting agent. The PBC, which is application-specific, lacks a generic definition and must be tailored for each innovation implementation.

The model also incorporates the notion of epistemic vigilance Mercier & Sperber (2011). Epistemic vigilance refers to a set of cognitive mechanisms that allow individuals to assess the reliability of information and its sources—such as the trustworthiness of the speaker, the coherence of the message, and the speaker’s intentions. In MIDAO, this notion is implemented by allowing an agent to reject arguments from another agent if it considers the other agent to be untrustworthy. More specifically, an Individual agent will not accept an argument from another agent with whom it has a significant difference in opinion (in terms of adoption intention). The extent to which an agent will consider another’s argument depends on its level of uncertainty about its own intention to adopt (\(u_i^I\)). As in the model by Deffuant et al. (2002), the more certain an agent is about its opinion, the less likely it is to be influenced by others’ opinions. The uncertainty of an agent is influenced by the arguments it knows and, more importantly, the confidence it has in the sources of these arguments. Additionally, the influence factor (\(IF_i\)) plays a role: a more influential agent’s arguments are more likely to be accepted than those of a less influential one.

Finally, MIDAO incorporates an argument forgetting mechanism, as proposed by Taillandier et al. (2021), to simulate memory limitations. If an agent neither uses nor receives an argument again, it will forget it. This is modeled through a lifespan associated with each argument known to the agent. The lifespan is reduced at each time step, and when it reaches zero, the agent forgets the argument. If the argument is used or received again, its lifespan is reset to its initial value, which is determined by a global parameter, \(LA_{init}\).

Design concepts

Basic principles. The model is grounded in several established theories and works. The first is Rogers’ theory of the diffusion of innovation, which forms the foundation of MIDAO. This theory’s five key elements (Innovation, Adopters, Communication Channels, Time, and Social System) as well as the five stages of the adoption process (Knowledge, Persuasion, Decision, Implementation, and Confirmation) are incorporated into the model. The second core theory in MIDAO is the Theory of Planned Behavior, which plays a crucial role in defining the agent’s opinion on adopting the innovation and has been widely applied in diffusion of innovation models. Finally, the agent’s attitude toward adopting the innovation, a central component of the Theory of Planned Behavior, is modeled using formal argumentation, specifically the framework proposed by Dung (1995). This framework has been enhanced to account for argument attributes and the acceptability semantics introduced by Amgoud et al. (2017).

Emergence. The model’s main outcomes—the evolution of the number of adopters—emerge from the interactions between Individual agents and CommunicationChannel agents.

Adaptation. There are multiple levels of adaptation in the model. First, Individual agents adjust their behavior based on their current adoption decision state. If they are in the Persuasion or Decision states, they actively seek information from other agents and communication channels. However, in the Implementation and Confirmation states, they only interact with other Individual agents, without seeking new information from the communication channels. Another level of adaptation involves the exchange of arguments between Individual agents. This exchange is driven by the arguments known to each agent, with each one attempting to present new arguments to persuade the other.

Learning. Individual agents acquire new arguments through interactions with other individual agents or by accessing communication channels.

Sensing. Individual agents can discern the opinions (intentions) of others, both to update their social norms and to decide whether to engage with the arguments presented by other agents.

Interaction. Individual agents engage with other Individual agents by exchanging arguments and updating their social norms, as well as with Communication channel agents to acquire new arguments.

Stochasticity. Several elements in the model incorporate stochasticity beyond the initialization phase. Individual agents in the Persuasion and Decision states have a probability at each simulation step to search for an argument from a communication channel. The selection of the communication channel is random, influenced by the agent’s habitual use of that channel. Similarly, the retrieved argument is chosen randomly from the available arguments in the selected channel. Likewise, in the Implementation and Confirmation states, they have a certain probability of acquiring a new argument, randomly selected from the set of arguments related to the innovation’s usage.

For agents in the Persuasion, Decision, Implementation, and Confirmation states, there is a probability – based on the number of their social network connections – for them to interact with another Individual agent. The interacting agent is randomly selected from the agent’s social network. Additionally, the choice of the first argument used in an exchange is stochastic, with the probability of selection directly proportional to the argument’s level of acceptability.

Observation. The key metric observed is the adoption rate (agents in the ‘Implementation’ or ‘Confirmation’ states), which includes both the rate of new adopters over a given period and the cumulative adoption rate. Additionally, the Individual agents’ intentions to adopt is of particular interest. Furthermore, we observe the final polarization of the agents’ intention.

The polarization is computed using the following equation:

| \[P = \frac{1}{|N|(|N|-1)}\sum_{i \ne j}^{i \in N, j \in N}{(d_{ij}- \gamma)^2} \] | \[(3)\] |

In this paper, we employ a continuous measure of polarization, defined as the average pairwise distance between agents’ opinions. As emphasized by Bramson et al. (2017), polarization is a multifaceted concept that can refer to various phenomena, including opinion extremity, bimodality, ideological alignment, or intergroup distance. While influential works such as Mäs & Flache (2013) and Proietti & Chiarella (2023) tend to define polarization primarily in terms of bimodal distributions or cluster separation, our measure aligns more closely with the intergroup distance interpretation. It provides a meaningful operationalization in the context of MIDAO, where opinion differentiation arises through cognitive and social mechanisms such as argumentation and social norms.

We acknowledge that this distance-based measure captures only one facet of polarization. Alternative approaches, such as size-parity-based metrics, offer complementary perspectives—such as that illustrated in the recent argument-based model by Dupuis De Tarlé et al. (2024).

Details

Initialization

The initialization of MIDAO involves the creation of arguments, Individual agents, and Communication channel agents, which can either be derived from existing data or generated randomly.

1. Arguments Creation. MIDAO begins by generating a set of arguments. The number of pro-innovation arguments (\(T_a = +\)) and con-innovation arguments (\(T_a = -\)) is determined by parameters \(N_{Arg}^{+}\) and \(N_{Arg}^{-}\).

- Each argument is assigned a criterion (\(C\)) and a source type (\(Ts_a\)) randomly chosen from predefined lists. The total number of criteria (\(N_C\)) and source types (\(N_{Ts}\)) are set by parameters.

- For each argument, a set of attacks is defined. Arguments can only attack those of the opposite type. The number of attacks per argument is drawn from a Gaussian distribution with a mean (\(\bar{N_{Att}}\)) and standard deviation (\(\sigma_{Att}\)). The target of each attack is chosen randomly among valid arguments.

2. Communication Channel Agents Creation. By default, a single Communication channel agent is generated. This agent can provide all arguments (\(Args_k\)) and remains passive (\(Ind_k = \emptyset\)), meaning it responds to queries but does not actively disseminate arguments.

3. Individual Agents Creation. A population of agents is generated based on the parameter \(N_{Ind}\).

- Initially, each agent’s attitude (\(a_i\)), and perceived behavior control (PBC) (\(p_i\)) are set to 0.0. social norm (\(s_i\)) is randomly drawn from a uniform distribution between -1.0 and 1.0.

- The importance of each criterion (\(C_i\)) and trust in each source type (\(Ts_i\)) for every agent are randomly drawn from a uniform distribution between 0.0 and 1.0. If a single criterion and source type are specified, their importance and trust values are set to 0.5.

- The attitude weight (\(w_i^a\)) is drawn randomly between 0.0 and 1.0, while the subjective norm weight (\(w_i^s\)) is set to \(1 - w_i^a\). For general applications without specific knowledge, the PBC weight (\(w_i^p\)) defaults to 0.0.

- Each agent’s influence factor (\(IF_i\)) is proportional to its number of social connections (\(|SN_i|\)) and is defined as \(|SN_i|/N_{Ind}\).

- The probability of using each communication channel is assigned randomly between 0.0 and 1.0. If only one channel exists (default case), its probability is set to 1.0.

- Agents are initialized with a set of arguments, distributed based on a Gaussian random draw with mean (\(\bar{N_{ArgDistrib}}\)) and standard deviation (\(\sigma_{ArgDistrib}\)). Arguments can be selected from pro, con, or all arguments, as determined by parameter \(T_{Args}\). The lifespan of each argument is randomly defined between 0 and \(LA_{init}\).

4. Social Network Creation. A social network (\(SN_i\)) is generated to link Individual agents. The network structure depends on the parameter \(SNType\), which specifies one of five types: complete, square lattice, small-world, scale-free, or random. Table 3 details the generation methods for these networks.

| Type | Generation algorithm | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Complete | All nodes are interconnected, meaning every Individual agent is connected to every other agent in the social network. (No additional parameters needed) | - |

| Square lattice | Distributes Individual agents on a square lattice and connects them to their neighbor | \(Vt\): type of neighborhood – Von Neumann (4) or Moore (8) |

| Small-world | Watts Strogatz algorithm (Watts & Strogatz 1998) | \(k\): number of nearest neighbors each node is connected to in a ring; \(p\): probability of re-wiring each edge |

| Scale-free | Barabási-Albert algorithm (Barabási & Albert 1999) | \(m0\): number of initial nodes; \(m\): number of edges of each new node added during the network growth |

| Random | For each agent, the number of connections is determined by a Gaussian random draw, and the connections are assigned randomly | \(\sigma_{sn}\): standard deviation of the number of connections |

Input Data

MIDAO does not use any input data to represent time-varying processes.

Submodels

Computing attitude from arguments. MIDAO calculates the attitudes of Individual agents using acceptability semantics applied to a weighted argument graph. In this graph, each argument is assigned a base strength. To determine the base strength of an argument known to a specific agent, the model considers the agent’s preferences for criteria and confidence in sources. Indeed, various studies, such as Sternthal et al. (1978), have already demonstrated the impact of source credibility on persuasive effectiveness. The base strength \(f_i(a)\) of an argument \(a\) for an agent \(i\) is calculated using Equation 4:

| \[ f_i(a) = Ts_i(Ts_a) \times C_i(C_a)\] | \[(4)\] |

Here, \(Ts_i(Ts_a)\) represents the trust agent \(i\) places in the source \(Ts_a\) of argument \(a\), and \(C_i(C_a)\) is the average importance value that agent \(i\) assigns to the criteria \(C_a\) associated with argument \(a\).

Once the base strength for each argument is determined, the acceptability of each argument is calculated. As mentioned earlier, we employ the Weighted Max-Based semantics, which evaluates the quality of an argument’s attackers to determine its acceptability, and which favors the base strength of the attacking argument over their cardinality. Specifically, we use an iterative computation method, with the process stopping when the acceptability values stabilize to within \(0.01\), equivalent to \(1\%\) of the maximum achievable acceptability value for any argument.

The final attitude of an agent \(i\) is then computed using a hyperbolic tangent function, which maps the sum of all acceptability values from the range \([-|Arg_i|, |Arg_i|]\) to a scale between -1 (indicating a unfavorable attitude towards innovation) and +1 (indicating an favorable attitude towards innovation). In fact, this function enables us to account for the accumulation of arguments in the same direction: an agent aware of only one argument in favor of the innovation, with average strength, will always be less likely to adopt it than an agent who knows several such arguments, also with average strength. Additionally, this function normalizes the attitude between -1 and 1, allowing us to aggregate it with social norms and perceived behavioral control to obtain a normalized intention, also ranging from -1 to 1. This function is formalized in Equation 5:

| \[ a_i = \frac{1 - \exp(-\alpha \sum_{a \in Arg_i}{Acc(a,i)})}{1 + \exp(-\alpha_a \sum_{a \in Arg_i}{Acc(a,i)})}\] | \[(5)\] |

Social Norm update. The subjective social norm reflects the social pressure influencing an individual’s opinion. To update this norm, we apply a rule adapted from the relative agreement model introduced by Deffuant et al. (2000). In the original model, an agent’s opinion is represented as a real-valued number that shifts incrementally toward the opinions of others, provided their views are not too dissimilar (i.e., within a bounded confidence threshold). In MIDAO, we reinterpret this mechanism in the context of perceived descriptive norms: rather than updating a personal opinion, the agent updates its internal representation of the average intention to adopt the innovation in its social environment.

When agent \(i\) interacts with agent \(j\), this equation adjusts agent \(i\)’s social norm based on the influence of agent \(j\) on \(i\):

| \[ s_i = s_i + \mu \times (1 - u_j^I) \times (I_j - s_i)\] | \[(6)\] |

The core of the update rule lies in the term \(I_j - s_i\), which represents the difference between the observed intention of agent \(j\) and the agent \(i\)’s current perception of the norm \(s_i\). This reflects a basic cognitive heuristic: if an agent repeatedly observes others expressing stronger intentions to adopt than expected, it will revise its perception of what is socially common or acceptable. Conversely, observing weak intentions will push the perceived norm downward. This dynamic captures the evolution of social expectations through exposure, a mechanism well supported in social psychology (Cialdini & Goldstein 2004).

Importantly, this rule complements – rather than duplicates – the mechanism of attitude updating through argument exchange. While argumentation models explicit persuasion and reason-based evaluation, norm updating reflects an implicit, often unconscious alignment with perceived social behavior. The coexistence of both mechanisms allows MIDAO to capture the dual nature of influence – social and cognitive – and to explore how their interaction can lead to various diffusion patterns, as shown in Experiment 4.25.

Intention uncertainty. Each time an Individual agent receives or forgets an argument, it updates its intention uncertainty according to Equation 7:

| \[ u_i^i = Max(0, 1 - \frac{\sum_{a \in Arg_i}{Ts_i(Ts_a)}}{N_{Arg}^{p \rightarrow a}})\] | \[(7)\] |

The underlying idea of this function is that an agent feels more confident when they are sufficiently informed, meaning when they are aware of a sufficient number of arguments from reliable sources. Therefore, this function depends not only on the quantity of arguments but, more importantly, on the credibility of the sources from which these arguments originate.

Dialogue between Individual agents. The algorithms implemented in MIDAO to simulate argumentative dialogue between Individual agents are inspired by MS Dialogue (Gabbriellini et al. 2013), which is grounded in the principles of Mercier & Sperber (2011), emphasizing that individuals engage in argumentative thinking.

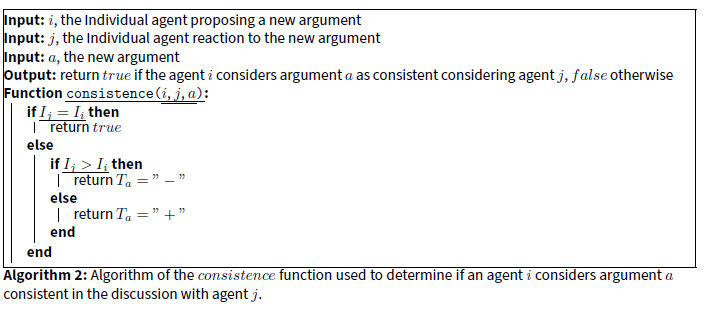

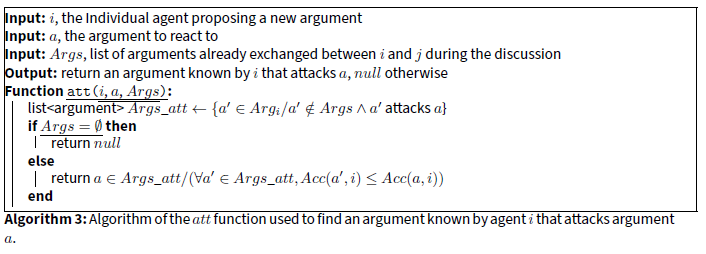

When an Individual agent \(i\) initiates a dialogue with another agent \(j\), it first selects an argument to present. This argument is randomly chosen from \(Arg_i\), with consideration given to the acceptability of the arguments. The probability of selecting an argument \(a\) is directly proportional to its acceptability \(Acc(a,i)\). The agent then triggers the \(reactArgument(i,j,a)\) action (Algorithm 1). This action enables the agent to either accept, reject, or respond with a new argument. The agent’s decision depends on the trust it has in the other agent, defined by the \(trust\) function (Algorithm 4), and its knowledge of arguments that challenge the proposed argument, as specified in the \(att\) function (Algorithm 3). The \(trust\) function enables the implementation of epistemic vigilance. ALGOS HERE

Experiments

General context

This paper investigates how cognitively grounded mechanisms – such as argument-based reasoning, perceived social norms, epistemic vigilance, and behavioral control – jointly influence the dynamics of innovation adoption within social networks. While a substantial body of work has studied innovation diffusion using formal or agent-based models, many of these models either simplify internal reasoning processes or treat social influence as a uniform force. MIDAO departs from these works by explicitly modeling the internal deliberation process of individuals using a modular architecture composed of three components – attitude, perceived social norm, and perceived behavioral control – that are updated based on argumentation and social interaction.

The overarching research question guiding this work is: How do the structure and content of interpersonal communication, together with individual cognitive mechanisms, shape the diffusion and adoption of innovations in structured populations?

This question aligns with recent calls in the literature for more integrated models that combine micro-level reasoning with macro-level diffusion patterns (Banisch & Olbrich 2021; Singer et al. 2019). The MIDAO framework is designed to respond to this gap by embedding a formal representation of argumentation into agent decision-making and linking it to social mechanisms.

In addition to classic model exploration experiments – such as observing output evolution over time and analyzing the influence of stochasticity – we conducted a series of experimental blocks designed to empirically explore the contribution of each cognitive mechanism and structural parameter within the model:

- Experiments (1) investigate the role of argumentation semantics in computing attitudes. Specifically, we test whether the choice of semantics—giving greater or lesser weight to the number of attacking arguments versus their strength—significantly influences model outcomes. This question connects to ongoing work in formal argumentation on how different semantics yield divergent acceptability results under uncertainty (Amgoud & Ben-Naim 2018).

- Experiments (2) assess the role of heterogeneity within the population, including differences in agents’ interpretation of arguments and their levels of trust in others. These experiments examine how such variability may lead to slower diffusion, fragmentation, or polarization, echoing findings from sociological studies on the uneven adoption of innovation and resistance to change (Rogers 2003; Valente 1996).

- Experiments (3) compare the impact of social norm updating versus argument-based attitude revision. While many classical models conflate social influence with behavioral conformity, MIDAO makes a clear distinction between normative pressure (descriptive expectations) and rational persuasion through argumentation, thereby offering a richer account of how individual intentions evolve (Cialdini & Goldstein 2004; Mercier & Sperber 2011).

- Experiments (4) explore the effects of the structure and balance of the argument set, particularly the distribution of pro versus con arguments. These experiments help identify threshold effects and tipping points in the adoption process, consistent with theories of critical mass and influence thresholds in innovation diffusion (Centola 2018; Valente 1996).

- Experiments (5) examine the role of influencers—agents with high centrality or credibility—in the diffusion process. These tests allow us to evaluate how localized influence can accelerate or reshape the spread of adoption, in line with empirical and theoretical studies on opinion leaders and network-based influence (Aral & Walker 2012; Watts & Dodds 2007).

- Experiments (6) focus on the influence of network topology, challenging the widespread assumption in many models that the network is a fixed or neutral structure. Our results demonstrate that certain network configurations – such as latice or scale-free topologies – can significantly alter diffusion dynamics, even when cognitive mechanisms and individual dispositions remain constant (Zhou et al. 2020).

The model was implemented using the GAMA platform (Taillandier, Gaudou, et al. 2019), which provides the advantage of an extension specifically designed for argumentation (Taillandier et al. 2019). All experiments were conducted in an abstract environment without the use of real data. The default parameter values used in the experiments are listed in Table 4.

MIDAO has been implemented as a plug-in for the GAMA platform. The code for this plug-in, along with all the experiments conducted in this section, is available in the project’s GitHub repository (Taillandier & Sadou 2025).

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(N_{Arg}^{+}\) | 25 | Number of pro arguments |

| \(N_{Arg}^{-}\) | 25 | Number of cons arguments |

| \(\bar{N_{Att}}\) | 2.0 | Mean of the Gaussian distribution for the number of attacks for each argument |

| \(\sigma_{Att}\) | 1.0 | Standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution for the number of attacks for each argument |

| \(N_C\) | 5 | Number of criteria |

| \(N_{Ts}\) | 5 | Number of sources |

| \(N_{Ind}\) | 100 | Number of Individual |

| \(\alpha_{exchange}\) | 100 | Frequency of exchange between Individual agents |

| \(I^{k \rightarrow p}\) | 0.1 | Intention threshold to move from Knowledge to Persuasion state |

| \(N_{Arg}^{p \rightarrow d}\) | 5 | Number of arguments needed to move from Persuasion to Decision state |

| \(I^{d \rightarrow a}\) | 0.5 | Intention threshold to move from Decision to Implementation state |

| \(T^{i \rightarrow c}\) | 200 | Time steps needed to move from Implementation to Confirmation state |

| \(CC_i(k)\) | 0.1 | Probability of finding an argument from the communication channel \(k\) |

| \(PU_i\) | 1.0 | Probability of obtaining new arguments through the use of the innovation |

| \(LA_{init}\) | 200 | Initial lifespan for the arguments |

| \(\alpha_a\) | 1.0 | The speed at which the attitude converges towards an extreme value |

| \(\mu\) | 0.1 | The speed of convergence of the social norms |

| \(SNType\) | Random | Social network topology |

| \(\bar{N_{sn}}\) | 6.5 | Mean of the Gaussian distribution for the number of individual relatives |

| \(\sigma_{sn}\) | 3 | Standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution for the number of Individual relatives |

| \(\bar{N_{ArgDistrib}}\) | 0.5 | Mean of the Gaussian distribution for the initial number of arguments for Individual agents |

| \(\sigma_{ArgDistrib}\) | 0.5 | Standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution for the initial number of arguments for Individual agents |

Regarding the outputs, we analyzed the adoption rates, the average intentions and the polarization.

Evolution of the outputs over time

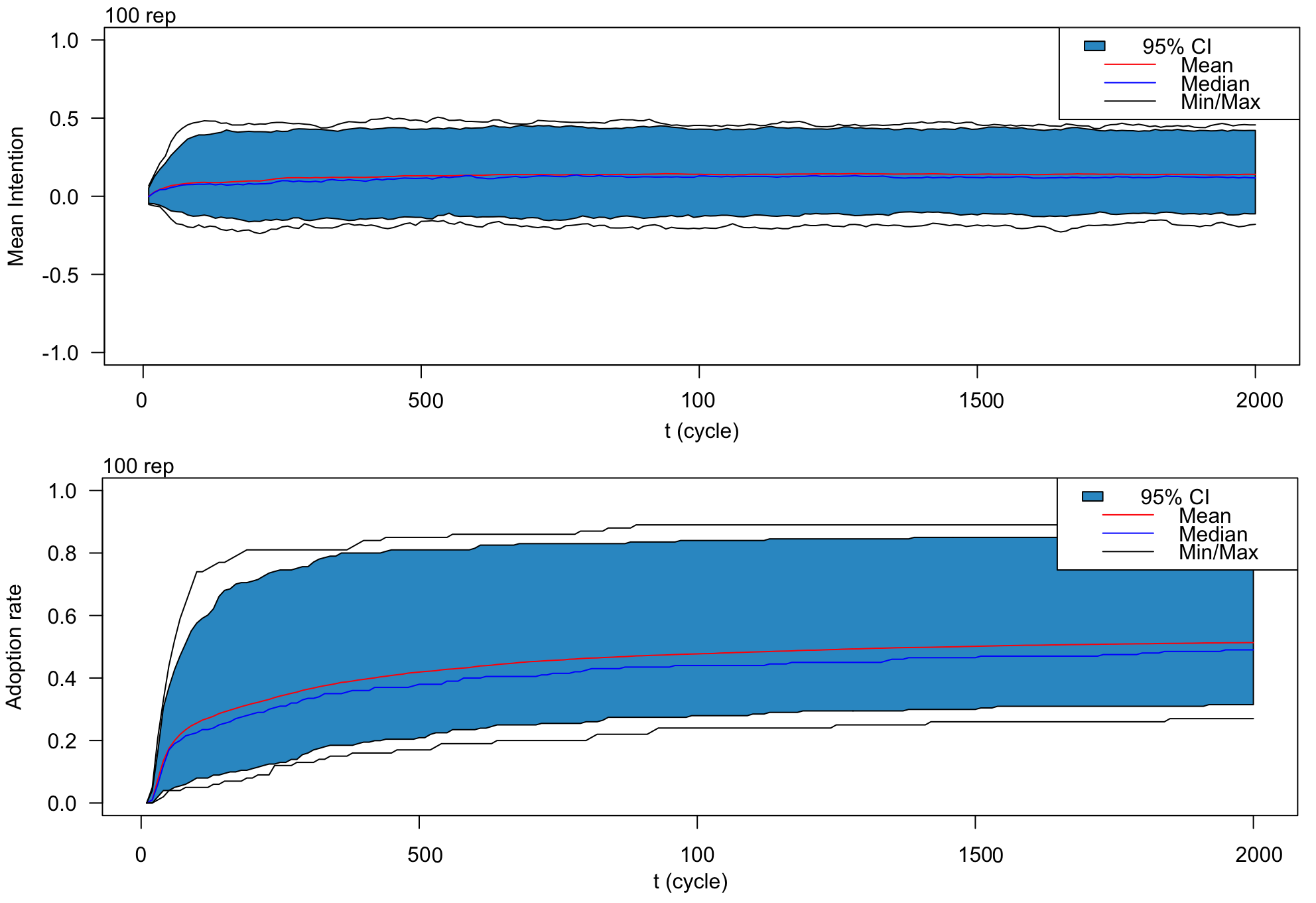

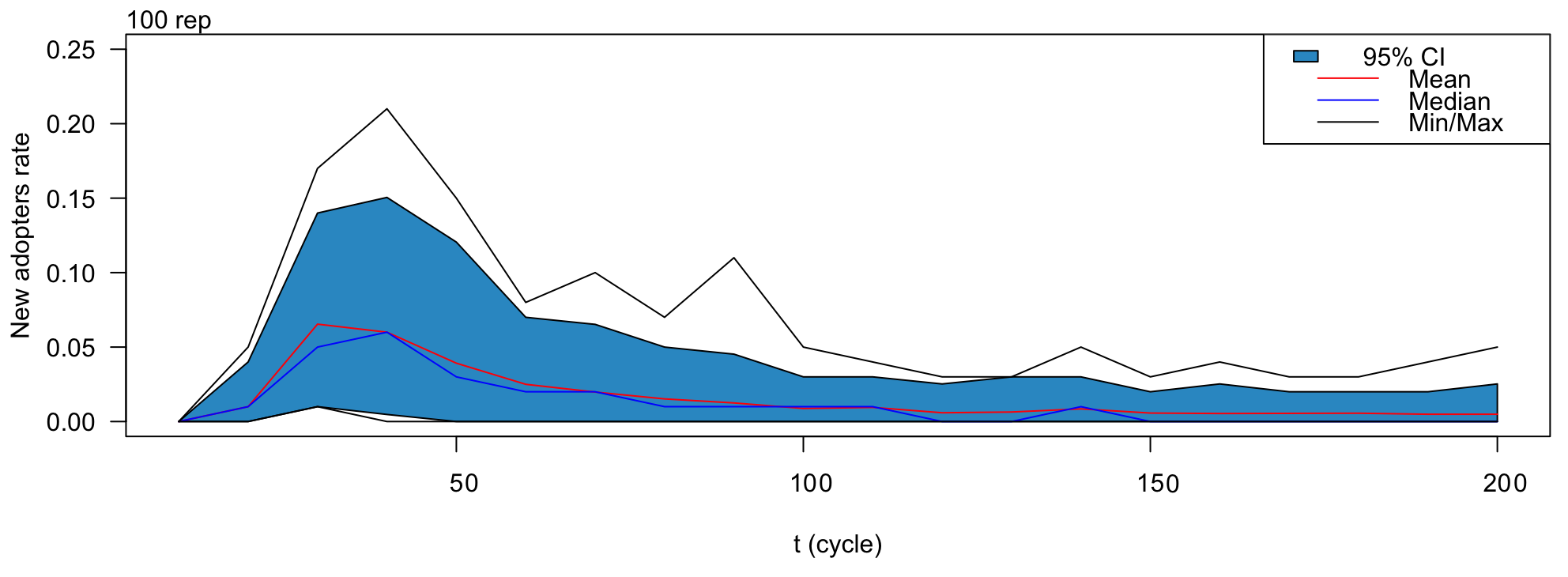

To determine the number of time steps required for the model to reach a state near stability with the default parameters, we ran the simulation for 2000 time steps. Figure 3 presents the results in terms of the adopter rate and average intention over time, based on 100 replications. Figure 4 illustrates the rate of new adopters calculated over the last 10 time steps throughout the simulation for the 200 first steps. Figure 5 presents the final mean intention, polarization and adoption rates.

The adoption curve of the innovation over time exhibits a classic normal distribution pattern (Rogers 2003). Initially, only a few individuals adopt the innovation, but we can see after a rapid rise in the number of adopters up to around 220 time steps. Subsequently, the growth slows until approximately 1,000 time steps, at which point the system approaches stability. The adoption rate stabilizes at roughly 0.52. Meanwhile, the average intention shows a slight increase during the initial 200 time steps before stabilizing around 0.1. Thus, despite half the arguments opposing the innovation, a short majority of individuals ultimately choose to adopt it. This can be attributed to Individual agents who, despite having only a small initial interest (persuasion state), begin actively seeking new arguments and engaging with others. Through these exchanges, they primarily share pro-innovation arguments, which further encourage others. This dynamic intensifies as more agents become interested in the innovation. Such a phenomenon helps explain why, in real-world scenarios, innovations with mixed pros and cons often achieve widespread adoption. A notable example is the global adoption of cellular phones, despite the balanced debate surrounding their advantages and disadvantages (Baloria 2018; Gondal & Mushtaq 2021; Rather & Rather 2019).

For subsequent experiments, we will focus on analyzing the first 1,000 time steps.

Analysis of MIDAO’s stochasticity

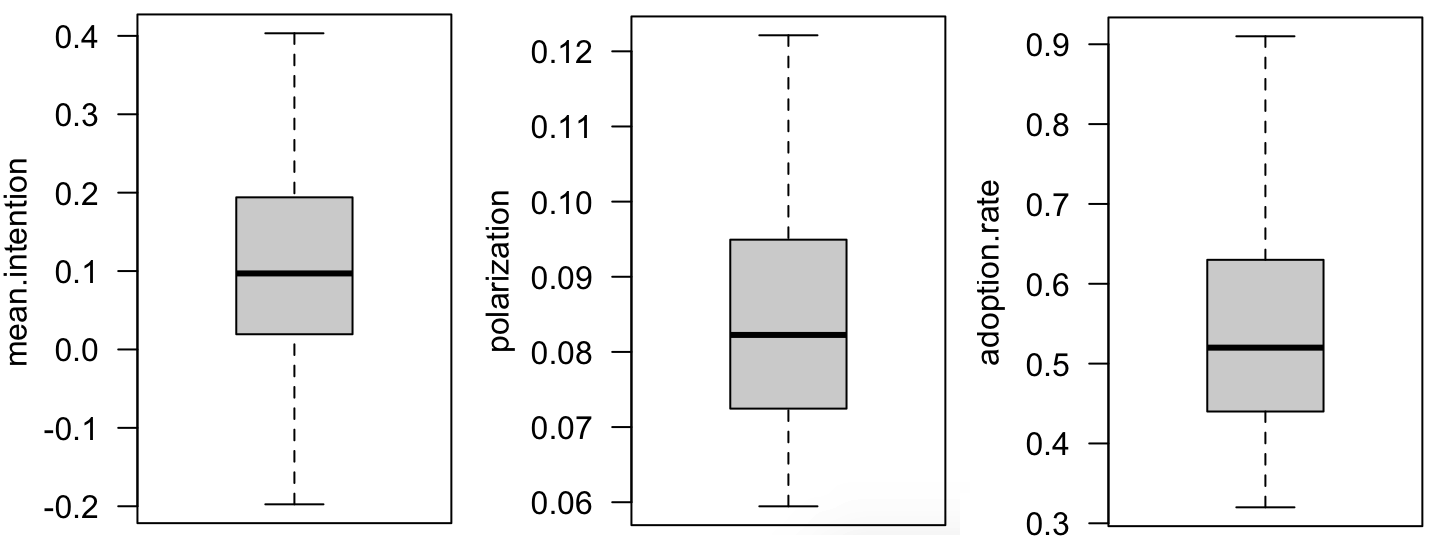

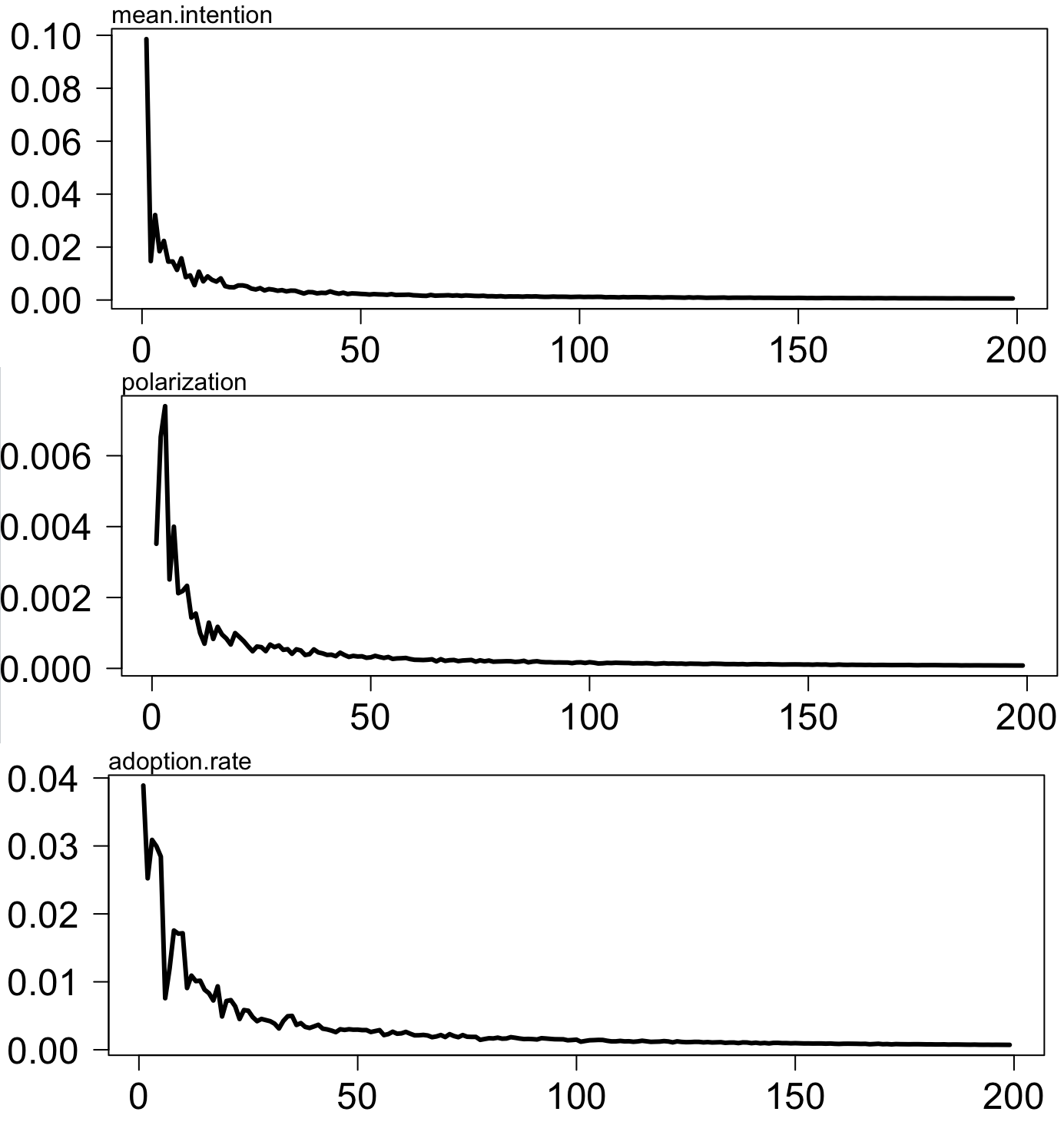

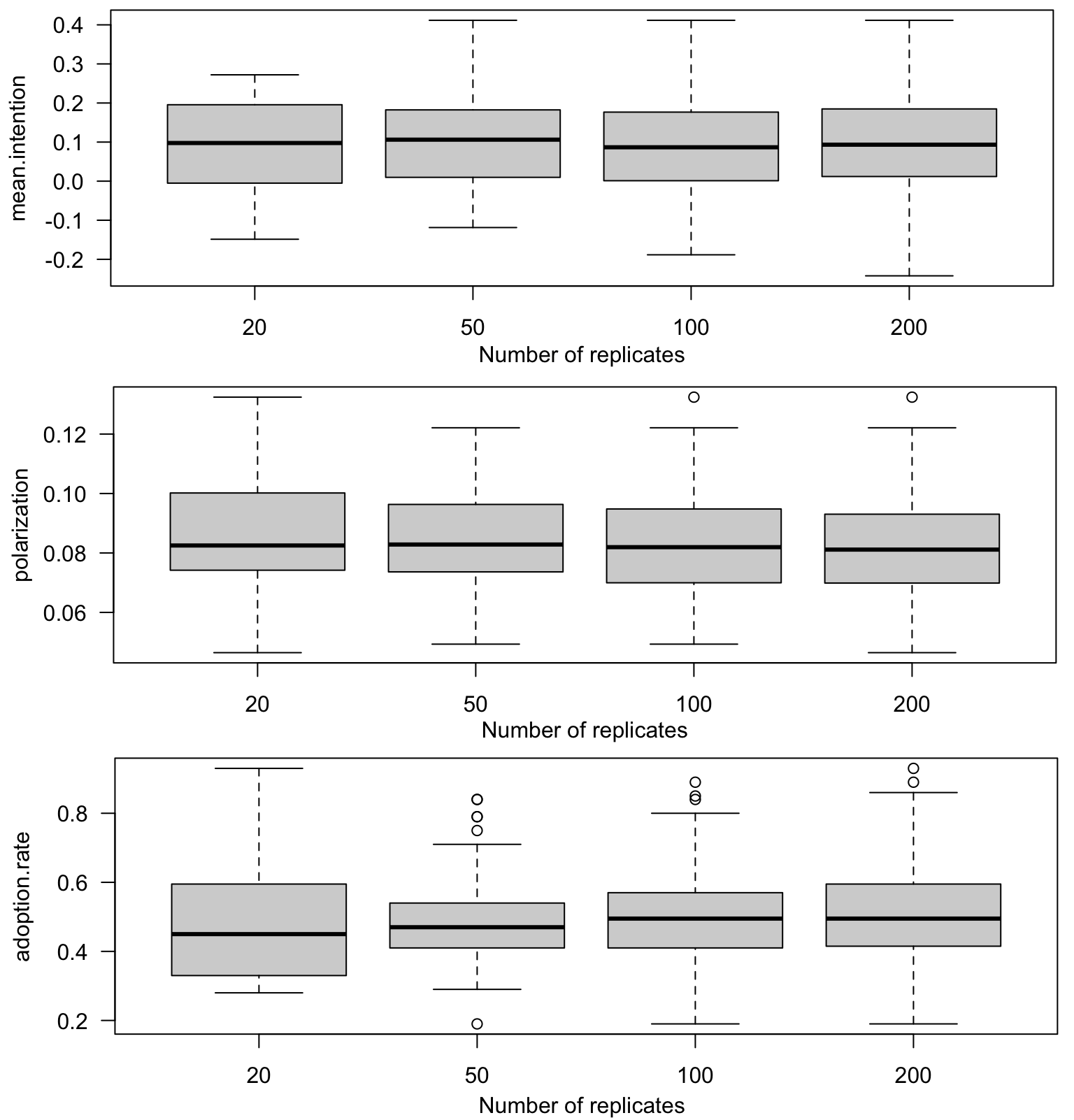

In this experiment, we examine the effect of MIDAO’s stochasticity on the results, particularly focusing on the adoption rate, the polarization and the average intention of the Individual agents. The primary goal is to identify a threshold value for the number of replications, beyond which further increases in the number of replications would not lead to a significant reduction in the marginal difference between the results. To achieve this, we compare the adoption rate, the polarization, and average intention across different numbers of simulation replications. The default parameters were used for this exploration. The simulation was run for 1,000 time steps.

Figure 6 illustrates the standard error of the mean intention, polarization, and adoption rate across varying numbers of replications. Figure 7 demonstrates the effect of the number of replications: the black line represents the median, the box indicates the interquartile range (second and third quartiles), and the whiskers depict the minimum and maximum values, excluding outliers (results that deviate from the median by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range).

The findings suggest that increasing the number of replications beyond 100 has minimal influence on the overall simulation trend.

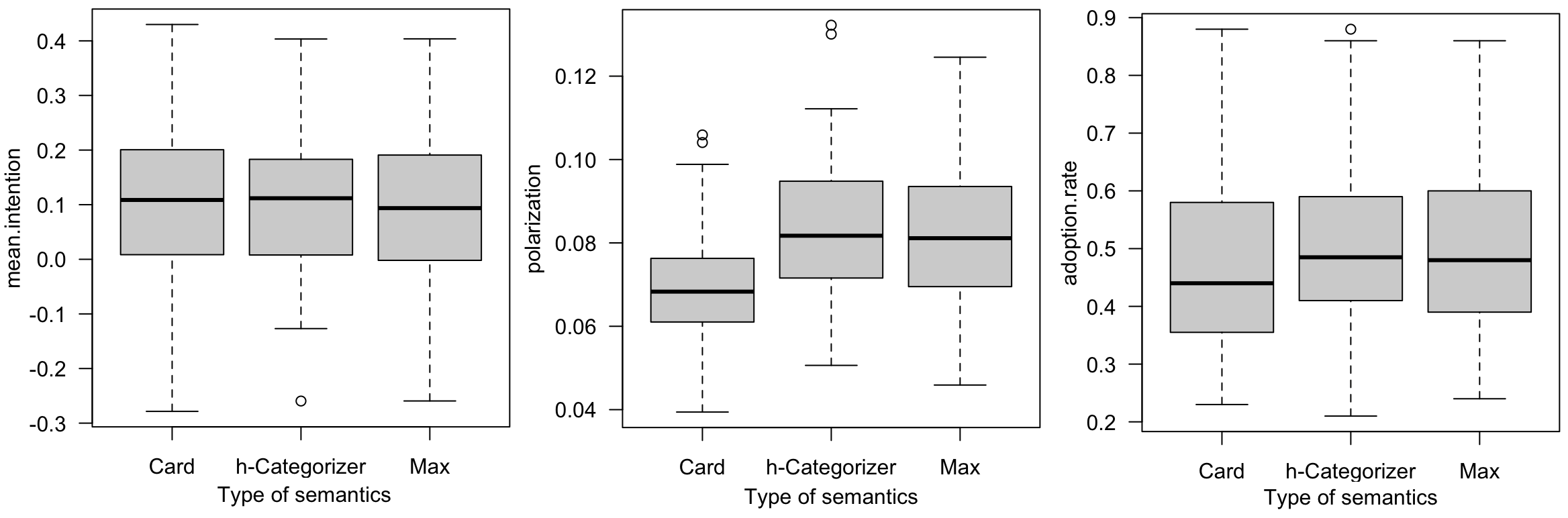

Impact of the semantics used to compute the attitude

A key feature of MIDAO is the use of arguments to calculate attitude. An important factor in this process is the choice of semantics for evaluating the arguments known by the agent. In this model, we adopted the Weighted Max-Based semantics proposed by Amgoud et al. (2017), which emphasizes the weight of attacks. However, other semantics could have been considered.

In this experiment, we compare the results obtained using the three semantics proposed by Amgoud et al. (2017): Weighted Max-Based, Weighted Card-Based, and Weighted h-Categorizer. We used the default values for all other parameters.

Figure 8 presents the final mean intention, polarization, and adoption rate for each of these semantics.

The first observation is that the three semantics yield similar average intention values, with no significant differences. However, the Weighted Card-Based semantics, which favors the number of attackers over the base strength of the arguments, shows a slightly lower level of polarization. Adoption rates are also very similar across the three semantics, although the Weighted Card-Based semantics exhibits a slightly lower adoption rate.

This result is not particularly surprising, given that the default parameter values used for the number of attacks between arguments are relatively low (an average of 2 with a standard deviation of 0.5), and that the impact of the semantics concerns the accounting of attacks.

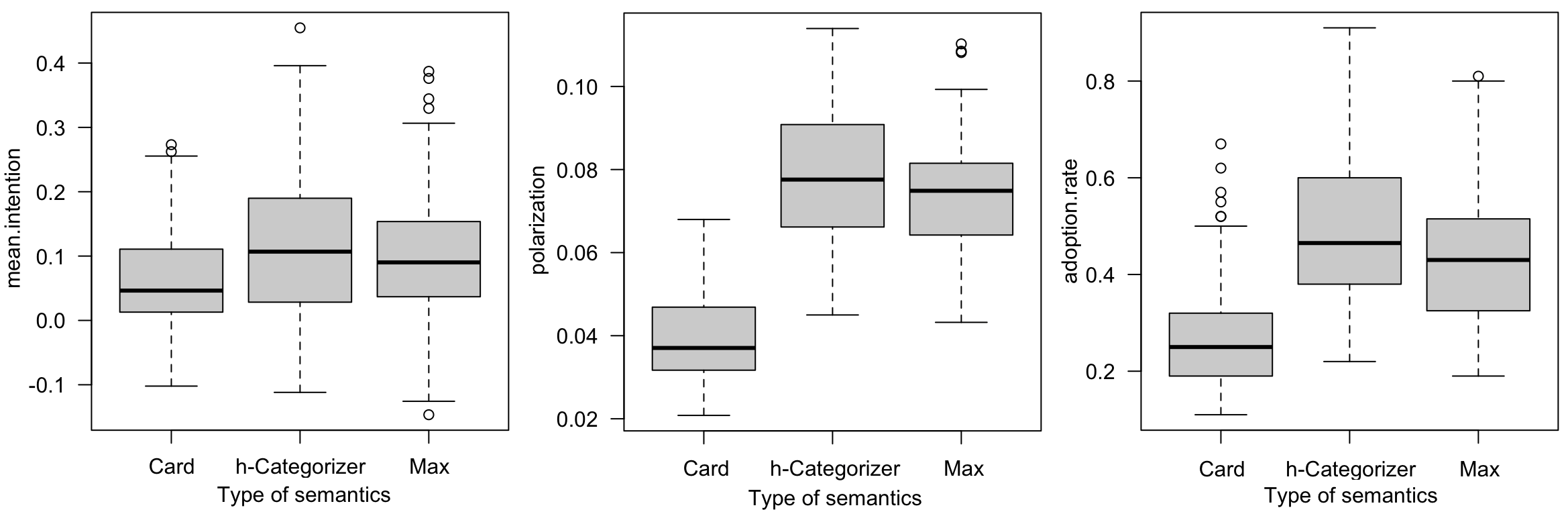

To further investigate, we propose testing the same semantics in a scenario with a significantly higher number of attacks between arguments. Figure 9 presents the final mean intention, polarization, and adoption rate for each of these semantics with a average of 10 arguments (standard deviation of 0.5).

This increased number of attacks amplifies the differences between the semantics. In scenarios with a high number of arguments attacking each other, the impact is particularly noticeable with the Weighted Card-Based semantics, which primarily considers the number of attacks relative to the initial strength of an argument. As a result, agents tend to converge toward a more homogeneous final intention, leading to much lower polarization but also slightly lower intention values. Consequently, fewer agents have an intention high enough to adopt the innovation.

The adoption rate is slightly higher with the h-categorizer semantics, as this semantics accounts for all attacks, not just those originating from the strongest argument. This broader consideration significantly reduces the number of arguments that fail to fully convince the agent, whether due to the source or the criterion being evaluated.

Impact of the heterogeneity of possible adopters

An advantage of the MIDAO model is its ability to account for individual heterogeneity across various dimensions: perception of arguments (criteria), trust in source types, and psychological profiles (e.g., weight of PBC). In this experiment, we investigate the impact of individual perceptions, focusing on criteria and source types. Specifically, we compare the outcomes using the default parameters (5 criteria and 5 source types) with those obtained when only a single criterion and source type are defined with a medium interest/trust (0.5), effectively standardizing perceptions so that all individuals view arguments in the same way. Figure 10 shows final mean intention, polarization, and adoption rate with and without heterogeneity.

The results reveal a higher adoption rate in the presence of heterogeneity, averaging 0.5 compared to 0.3. This can be attributed to the fact that in heterogeneous populations, certain individuals may be strongly influenced by specific arguments rather than relying on an average evaluation. These highly convinced individuals become key drivers, actively engaging with others to shift opinions by exchanging arguments and influencing the social norm. However, in a heterogeneous population, we observe a lower average intention. This phenomenon can be explained by examining polarization: in the heterogeneous population, polarization is significantly higher. As a result, there are more agents who are strongly convinced—enough to adopt the innovation—while others remain completely unconvinced.

This experiment highlights the significance of population characteristics and demonstrates the importance of accounting for variations in argument perception. MIDAO effectively incorporates these differences, providing a more nuanced understanding of adoption dynamics.

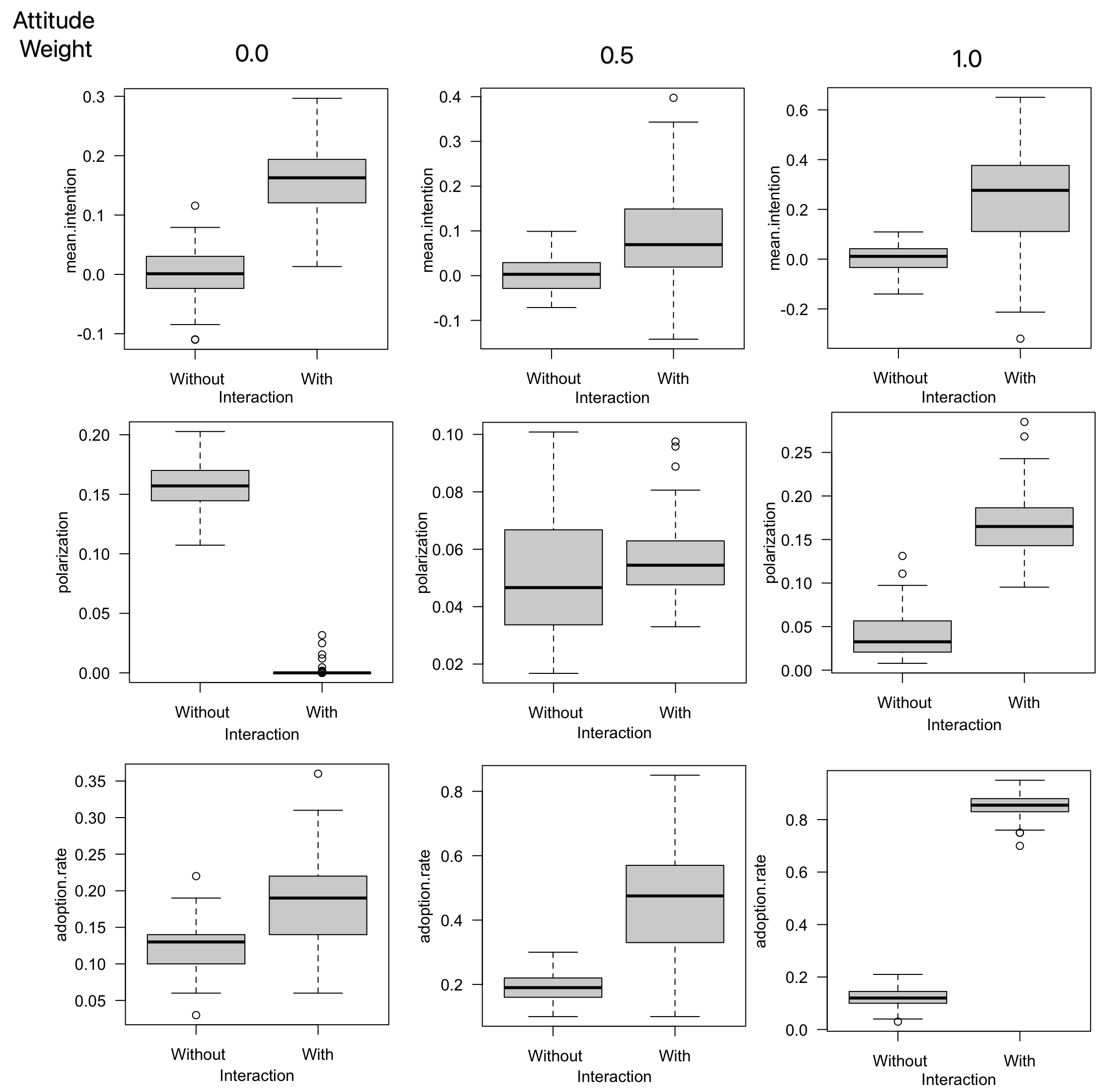

Impact of attitudes and social norms

The MIDAO architecture integrates two mechanisms that influence an agent’s adoption intention: social norm updating and argument-based attitude revision. While both affect the same variable (intention), they operate through distinct psychological pathways and are grounded in different theoretical traditions. Social norm updating is inspired by bounded confidence and relative agreement models (Deffuant et al. 2000), and captures how individuals adjust their intentions based on the perceived behavior of peers in their local network. In contrast, the argumentation component builds on formal argumentation theory and opinion dynamics through content-based exchanges (Mäs & Flache 2013), allowing agents to revise their attitudes based on the evaluation of reasons and the trustworthiness of sources. This dual mechanism reflects well-established findings in social psychology distinguishing between descriptive norm influence (what most people do) and informational or persuasive influence (why people believe something) (Cialdini & Goldstein 2004; Mercier & Sperber 2011). Including both in the model is not meant to artificially amplify influence but to reproduce real-world decision processes, where individuals often weigh both how many people adopt a behavior and why they do so.

To ensure that this integration does not introduce unintended feedback loops or redundancy, we conducted targeted experiments to isolate and combine both effects. To achieve this, we propose testing the model by isolating each type of interaction, assigning zero weight to the other, to assess their respective effects. Specifically, we test the model using the default parameters but replace the random weight assigned to attitudes (and consequently to social norms) with fixed values of \(0.0\), \(0.5\), and \(1.0\). This results in corresponding values of \(1.0\), \(0.5\), and \(0.0\) for the weight assigned to social norms. Furthermore, in order to isolate the impact of social interactions from adoption without them, we tested for the three weight values with and without interaction. Figure 11 shows the final mean intention, polarization, and adoption rate for the different attitude weight values and with/without interaction.

The results indicate that, regardless of the type of social interaction, both the average intention and adoption rate are higher with interaction than without.

One particularly noteworthy aspect is polarization. When social influence alone is considered, intentions naturally converge toward a single value, resulting in low polarization (close to 0.0). In contrast, polarization is highest when interactions are based solely on arguments. This can be explained by the fact that agents only accept arguments from others when their viewpoints are not too dissimilar.

When both processes – social influence and argument exchange – are taken into account simultaneously, they tend to counterbalance each other, leading to low polarization. However, polarization remains slightly higher compared to scenarios without interaction.

Another key observation is that adoption is significantly higher when only attitude is considered. Conversely, adoption is lowest when only the social norm is taken into account. Interestingly, in the scenario where only social norms are considered, the final average intention is higher than in the case where both attitude and social norm are included. However, adoption is higher when both processes are considered. This discrepancy can be attributed to the higher polarization observed when both mechanisms are active: some agents develop a negative opinion of the innovation, while others become sufficiently positive to adopt it.

Impact of the number of pro and con arguments

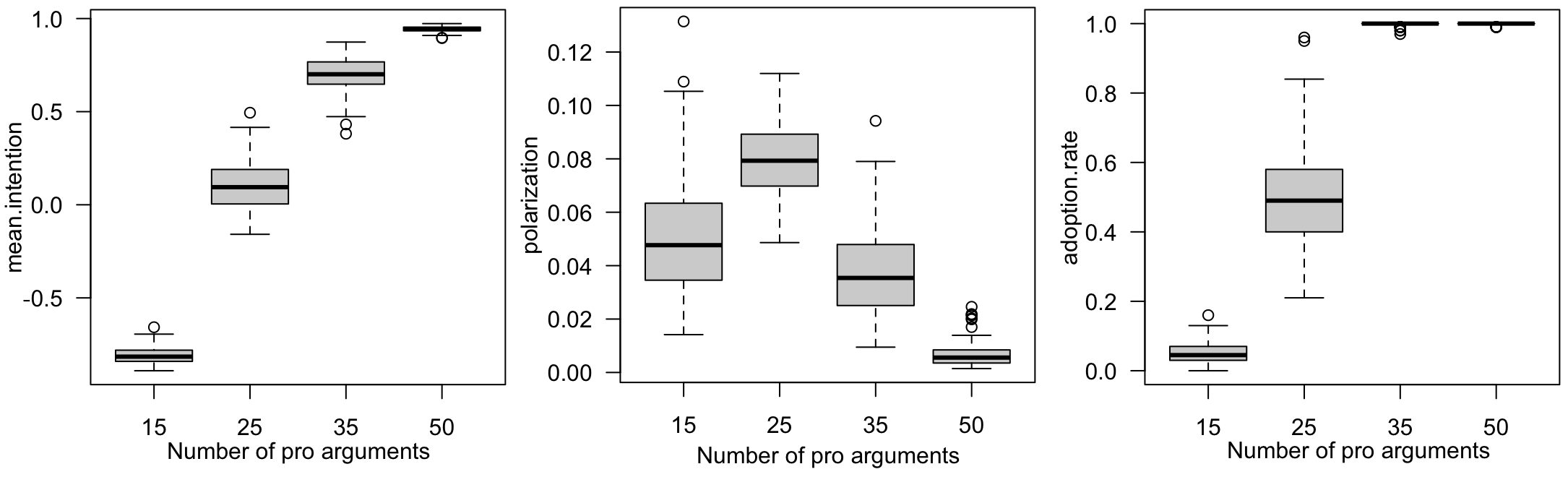

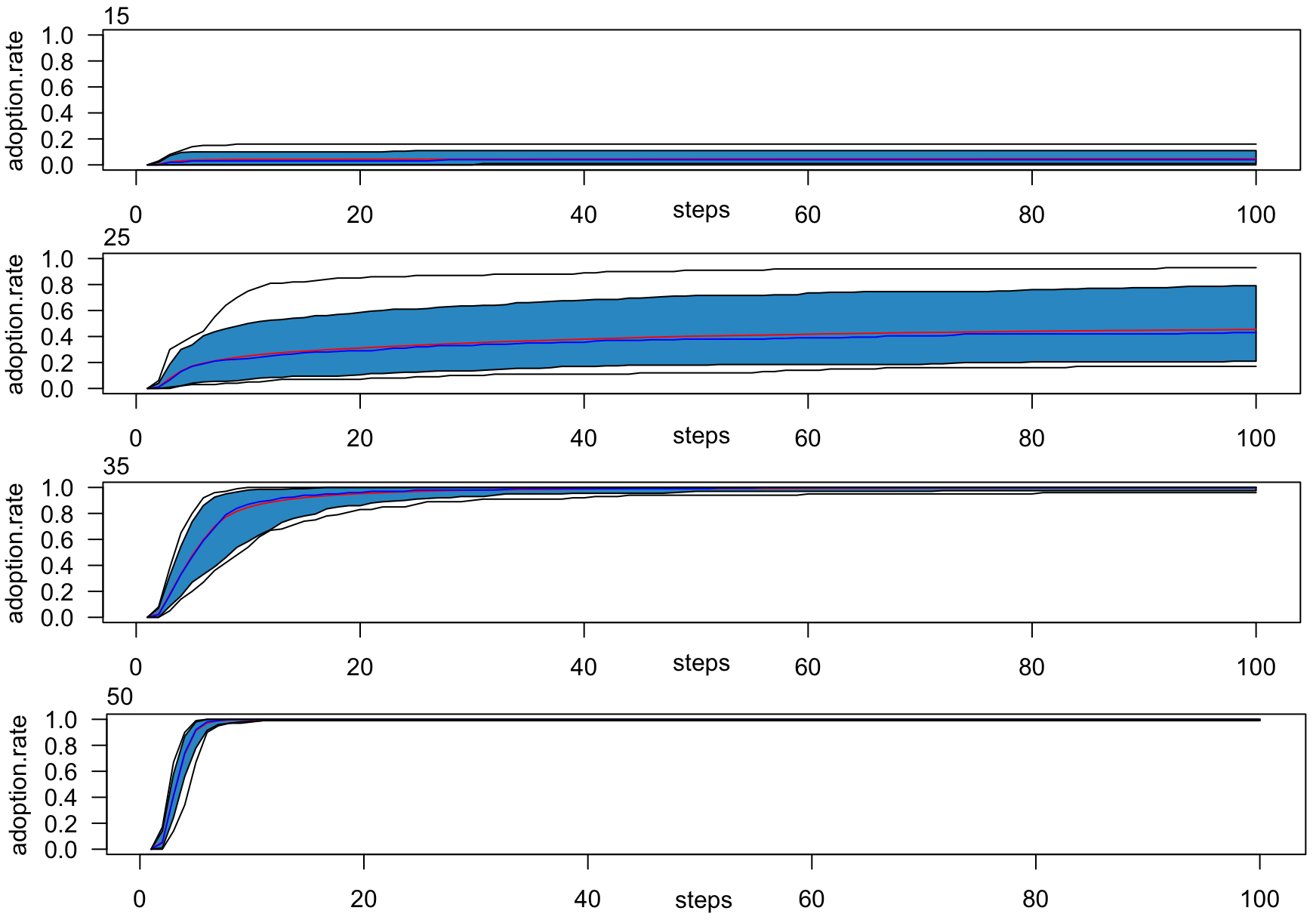

We investigated the impact of the number of arguments supporting or opposing the innovation on the adoption process. To do this, we conducted simulations (100 replications) with varying numbers of pro-innovation arguments: 15, 25, 35, and 50. All other parameters were set to their default values (50 arguments). Figure 13 illustrates the adoption rate dynamics for the different numbers of pro-innovation arguments, while Figure 12 presents the final mean intention, polarization, and adoption rates.

An important observation is that it is not necessary to have only pro arguments to achieve a full adoption rate of 1.0. For instance, even with 35 pro arguments, the adoption rate reaches 1.0, despite the mean intention being less than 0.75. The primary difference between having 35 and 50 pro arguments lies in the adoption dynamics: with fewer pro arguments and more cons, the time required to reach full adoption is longer.

As the number of pro arguments decreases, the adoption curve flattens. In cases where there are only 15 pro arguments out of 50, the adoption rate remains low, with a final level below 0.1 and a negative mean intention (less than -0.5). Additionally, the convergence towards the maximum adoption level is significantly delayed.

Polarization is particularly high when the number of pro-innovation arguments equals the number of counterarguments. In contrast, it remains very low when all arguments favor the innovation.

In summary, the balance of pro and con arguments has a profound effect on innovation adoption, influencing both the temporal dynamics and the total number of adopters.

Impact of influencers

The objective of this experiment is to evaluate the influence of key individuals on the diffusion of innovation. Specifically, we begin with a subset of individual agents designated as innovation relays – agents (influencers) equipped with a large number of pro-innovation arguments. These agents represent the most influential members of the network, identified by their extensive social connections (i.e., the highest degree of connectivity).

For the experiment parameters, default values are applied except for the initialization of influencers’ arguments. Each influencer’s initial argument list is populated with \(N^{\text{influencer}}\) arguments randomly selected from the set of pro-innovation arguments. The value of \(N^{\text{influencer}}\) is drawn from a Gaussian distribution with a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 2. Additionally, arguments’ lifespans are set to their maximum allowable value (\(LA_{\text{init}}\)).

Figure 14 shows the final adoption rates as a function of different proportions of influencers within the network.

The results highlight the significant impact of influencers on adoption rates. Without altering the initial pool of arguments (25 pro and 25 cons), the proportion of influencers positively correlates with the number of adopters. Even with a minimal influencer presence (influencer rate = 0.01, i.e; just one influencer), the mean adoption rate increases, rising from 0.52 to 0.54. At an influencer rate of 0.25, the mean adoption rate approaches 0.9.

These findings align with the Motivational Theory of Role Modeling proposed by Morgenroth et al. (2015). According to this theory, certain individuals can influence the motivation of others and facilitate the adoption of new goals by serving as behavioral models, illustrating what is possible, and providing inspiration.

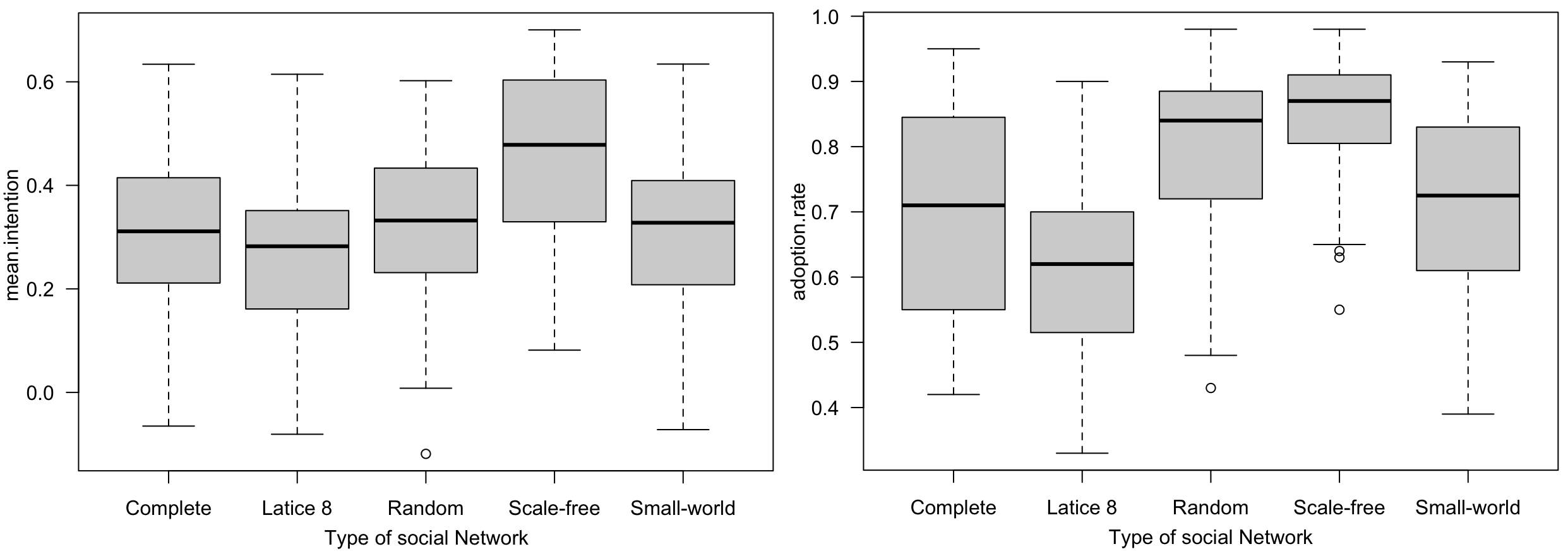

Impact of the social network

The goal of this experiment is to determine the impact of the type of social network on the diffusion of innovation as several studies have specifically highlighted the influence of social network topology on the spread of innovations (Delre et al. 2010; Sáenz-Royo et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2020). For the parameters, the default values were used. Table 5 shows the parameters used for the social network. The parameter values were chosen to have a close average number of connections per Individual agent (except for the complete graph) in order to facilitate comparisons. We also assume a proportion of 0.1 influencers, using the same parameter settings as in the previous experiment.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| \(Vt\) | Moore (8) |

| \(k\) | 6 |

| \(p\) | 0.5 |

| \(m0\) | 8 |

| \(m\) | 6 |

| \(\bar{N_{sn}}\) | 6.5 |

| \(\sigma_{sn}\) | 3 |

Figure 15 shows for 100 replications and 1000 time steps, the mean intention, and the rate of adopters for the different types of social network.

The results indicate that the type of social network significantly affects adoption rates. Specifically, adoption is markedly lower in lattice and small-world networks compared to other network types. This can be attributed to the fact that influencers in these networks have fewer connections and therefore exert less influence on other agents. In contrast, the highest adoption rate was observed in the scale-free network. This is likely due to its degree distribution following a power law, where influencers have a disproportionately high impact.

Interestingly, while the average adoption rate varies significantly across networks, the intention to adopt remains relatively consistent. This suggests that even small differences in intention can lead to substantial variations in adoption rates.

In summary, this experiment demonstrates that the structure of the social network plays a crucial role in the diffusion of innovation, particularly when influencers are involved in the process.

Conclusion

This paper presents MIDAO, a model of innovation diffusion grounded in Rogers’ stages of innovation, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and formal argumentation. The model contributes to research on the use of argumentation theory to study opinion diffusion and enables the analysis of how new arguments influence agents’ opinions and decisions to adopt an innovation. MIDAO captures both the social and psycho-cognitive dimensions of the innovation diffusion process. The social aspect is represented through the social norm, which reflects the societal pressure on individuals to adopt or reject the innovation. The psycho-cognitive aspect is captured through the attitude, which stems from the agent’s personal evaluation of the innovation for their own use. This evaluation accounts for the agent’s preferences based on specific criteria, as well as the perceived credibility of information sources. Our model also addresses the contradictions in the information received by agents (i.e., pro and con arguments). These contradictions are resolved through the agent’s subjective evaluation of each argument, which considers both the agent’s preferences and the credibility of the sources, along with the interconnections between arguments (specifically, attack relationships). Unlike approaches that treat arguments as isolated elements, our model emphasizes the importance of these relationships, particularly how arguments can undermine each other through attacks.

The experiments carried out reveal several key insights. First, accounting for population heterogeneity is crucial for understanding innovation adoption. Second, the number of pro-innovation arguments significantly affects adoption rates. With a balanced set of pro and con arguments, a short majority of the population may still adopt the innovation, but influencers play a critical role in accelerating this process. Finally, the type of social network significantly impacts innovation diffusion. Unlike many studies that default to a single network type without justification, our results demonstrate that network structure strongly influences the adoption process. Notably, there are notable similarities between the results obtained with MIDAO and those from Deffuant et al. (2005) model of innovation diffusion as both approaches emphasize the dual role of social influence and individual evaluation in shaping adoption behavior. Like Deffuant’s model, MIDAO shows that innovations with high social acceptance can spread widely – even when individual benefits are medium – due to strong normative pressure and information propagation. Furthermore, both models reveal the potential impact of minorities or “extremists” in shifting the overall dynamics, with MIDAO reproducing similar tipping effects through highly connected or influential agents. These parallels suggest that MIDAO is able to generalize some core insights of earlier diffusion models but also provides new explanatory tools to understand the construction of individuals’ internal opinions on the innovation. Taken together, the experiments conducted with MIDAO not only replicate well-established phenomena in the innovation diffusion literature – such as S-shaped adoption curves, tipping points, and opinion clustering – but also go further by explaining how and why these patterns emerge, based on internal cognitive and social processes. In this sense, MIDAO offers a conceptual and methodological bridge between cognitively plausible models of individual reasoning and macro-level diffusion patterns, thus providing a complementary perspective to simpler models that abstract away from the agent’s internal structure and deliberation.

While MIDAO is not primarily designed for prediction, its added value lies in its ability to serve as an explanatory tool. Unlike classical models that focus on reproducing macroscopic diffusion curves through simplified interaction rules, MIDAO enables the formulation and testing of mechanistic hypotheses about the cognitive and social dynamics that drive adoption. For instance, it allows researchers to isolate the impact of source credibility, epistemic filtering, or argument structure on the evolution of intentions. This capacity to open the “black box” of agent reasoning makes MIDAO particularly well-suited for applications where understanding why and how adoption occurs is as important as whether it does. Thus, the model extends beyond curve-fitting to offer a generative explanation of the internal processes that underpin collective outcomes.

The next step is to apply this generic model to a specific case study. A notable challenge lies in data collection. Implementing the model requires detailed data on actors’ arguments and their socio-psychological profiles, such as TPB component weights and thresholds for adoption state transitions. To address this, we have developed a mixed-method survey protocol combining behavioral economics and psychology approaches to gather the necessary qualitative and quantitative data. Currently, we are working on applying the model to study the adoption of smart water meters in Southwest France (Couture et al. 2025). Research has shown that these technologies could help farmers optimize water resource management. However, issues of acceptability have slowed their adoption. Our aim is to use the model to identify barriers to adoption and strategies to overcome them, facilitating better water management. Additionally, we plan to integrate AI techniques, such as deep reinforcement learning, to design policies that effectively promote the adoption of these technologies (Vinyals et al. 2023).

While this model represents an initial proposal for integrating the theory of planned behavior with argumentation to simulate innovation diffusion, several of the choices made in its design could have been approached differently. For instance, arguments could have been formalized in alternative ways, such as explicitly representing the innovation as a node in the graph and incorporating both support and attack links between arguments, as suggested in the work of Amgoud & Ben-Naim (2018). This approach would have enhanced the richness of the argumentation graph. The adoption process and transitions between states could also be enhanced. For instance, for the transition from the ‘Persuasion’ to the ‘Decision’ state, we chose a fixed threshold based on the number of arguments known by the agent. This simplification was made to streamline the process and does not take into account the nature or evaluation of the arguments. However, this transition could be further refined by integrating additional factors. For example, the consistency of the arguments from the agent’s perspective, as well as the perceived reliability of their sources, could significantly influence whether the agent feels sufficiently informed to proceed in the adoption process. Similarly, in our model, once the agent reaches the ‘Confirmation’ state, it will either continue or stop using the innovation while engaging in discussions with others. This state could be further refined by incorporating the concept of cognitive dissonance, allowing the agent to reassess their decision if they perceive that the anticipated benefits of adopting the innovation are not being realized.

MIDAO could be further enhanced to better capture specific socio-cognitive dynamics. For instance, while the distinction between adopters and non-adopters is already implicitly addressed – since adopters can acquire new arguments through their experience with the innovation and share them with others – the model could be refined to make this differentiation more explicit. It is already possible to consider the origin of an argument, such as giving greater weight to arguments based on personal experience. However, integrating more explicit mechanisms to formalize this distinction, similar to the approach proposed in Córdoba & Garcı́a-Dı́az (2020), could enhance the realism of the model.

Funding