Modelling Maize Agriculture by the Pre-Columbian Casarabe Culture of Amazonian Bolivia: An Agent-Based Approach

, ,

and

aDepartment of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Meteorology, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom; c Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (4) 5

<https://www.jasss.org/28/4/5.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5736

Received: 18-Sep-2024 Accepted: 12-Aug-2025 Published: 31-Oct-2025

Abstract

Scholars have long debated the extent to which pre-Columbian (pre-1492 CE) indigenous cultures modified and ‘domesticated’ the landscapes of Greater Amazonia. Compelling evidence to support large-scale pre-Columbian landscape modification can be found in the forest-savanna mosaic environments of northern Bolivia, where the Casarabe Culture constructed hundreds of earthen settlement mounds, integrated by a vast causeway-canal network. Operating between 400 and 1400 CE, recent research suggests this culture practiced a form of low-density agrarian urbanism. However, as just two mounds have been excavated in any detail and few palaeoecological data are available, little is known about the extent to which this culture modified the surrounding forest and savanna ecosystems. Here, we present the results of experiments conducted with an exploratory agent-based model of the Casarabe Culture, which we developed to generate hypotheses regarding how they utilised this landscape under a range of different scenarios. Based on our model outputs, we hypothesise that the Casarabe Culture only modified localised areas of the landscape, driven by their desire to maximise cultivation on land with ‘desirable’ environmental characteristics. For this same reason, land that possessed characteristics desirable to the Casarabe Culture is likely to have been intensively modified. More than sufficient forest and savanna was locally available to most settlement mounds to facilitate cultivation without the Casarabe Culture needing to encroach into undesirable areas, but their close spacing also suggests that a level of inter-settlement cooperation may have been necessary. The outputs of our model will play an important role in guiding future research on the Casarabe Culture, identifying viable sites of interest for archaeological and palaeoecological fieldwork. They can also be compared with future empirical research as it becomes available, improving our understanding of past underlying human-environment interactions on these landscapes.Introduction

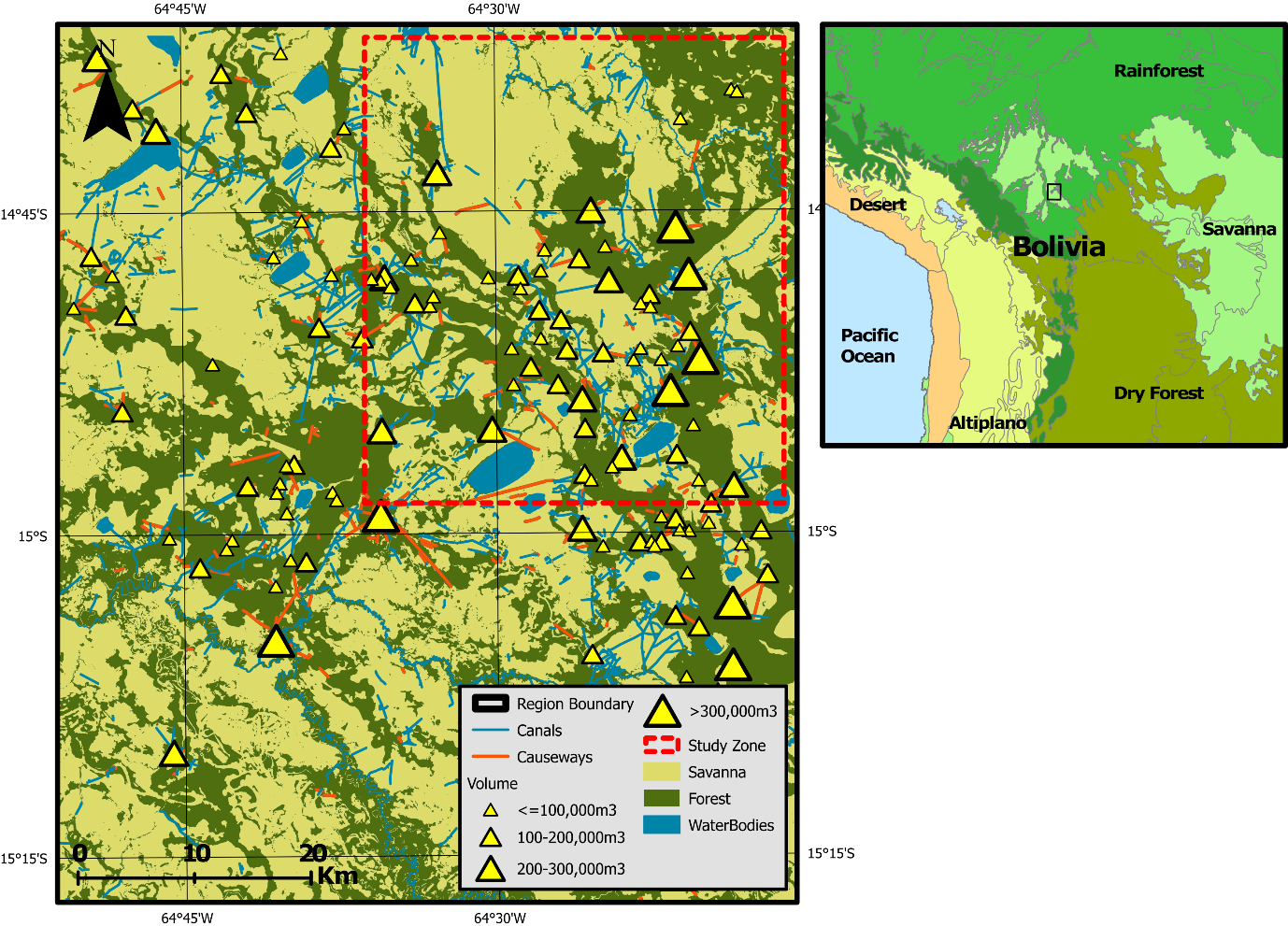

The extent to which Amazonian landscapes embody a legacy of pre-Columbian (pre- 1492 CE) human activity has long been debated (Bush et al. 2015; Montoya et al. 2020; Stahl 2002; Viveiros de Castro 1996). Compelling evidence that their activities led to large-scale landscape domestication can be found in the Llanos de Moxos (LM), a large (120,000 \(km^{2}\)) seasonally flooded forest-savanna mosaic landscape in northern Bolivia. Although primarily used for cattle ranching and mechanised rice agriculture today (Denevan 1963; Gobierno Autonomo del Beni 2019; Lombardo 2023), the LM is well-known for its wide abundance and variety of earthen structures built by pre-Columbian cultures during the late Holocene (Erickson 2006; Lombardo et al. 2011). Perhaps most prominent are the earthworks of the LM’s southeastern sector, a region occupied by the now-extinct Casarabe Culture between 400 and 1400 CE (Jaimes Betancourt 2012, 2015). On this landscape, the Casarabe Culture constructed over 189 earthen mounds (lomas), each covering up to 20 ha in surface area and potentially reaching 20 m in height, integrated within a dense matrix of causeways, canals, and lakes (Figure 1; Lombardo & Prümers 2010). Recent LiDAR scans highlight the scale and spatial complexity of these features, which have led to the Casarabe Culture being proposed as the first-known case of low-density agrarian urbanism in pre-Columbian Amazonia (Fletcher 2009; Prümers et al. 2022).

Little is known about the extent to which this culture utilised and modified the forests and savannas surrounding their earthworks. They are known to have utilised a variety of cultigens, including maize, manioc, squash, yams, peanuts, beans, cotton, peppers, and various palm fruits (Bruno 2010, 2015; Dickau et al. 2012). Unlike modern indigenous groups, which primarily subsist on manioc (Dufour 1994), local archaeobotanical records (Dickau et al. 2012; Lombardo et al. 2025), as well as skeletal carbon isotope studies (Hermenegildo et al. 2024), show that maize was the Casarabe Culture’s main dietary staple. However, questions remain regarding the specific locations and extent to which the Casarabe Culture chose to modify the surrounding landscape. This culture is known to have utilised their extensive canal and pond system as a drainage and irrigation network to cultivate maize in the open savannas (Lombardo et al. 2012, 2025; Whitney et al. 2013), constituting a previously unknown form of agriculture employed by pre-Columbian Amazonians. Yet, they could have also cultivated crops in forested areas, similar to modern indigenous groups (Holmberg 1969; Huanca 1999; Piland 1991), though likely using different methods (Denevan 1992a). Some scholars argue that this culture deforested the wider landscape, mobilising it for agriculture and enriching it with economically useful species (Erickson 2006; Erickson & Balée 2006). Others propose that their environmental impact was more localised, and that regional forest cover was maintained (Whitney et al. 2013). This raises questions around the extent to which the forests of the southeastern LM are largely natural or were domesticated by the activities of the Casarabe Culture (Erickson 2008; Langstroth 2011).

In this study, we describe the development of, and experiments conducted with, a bespoke agent-based model that we constructed to explore how the Casarabe Culture might have utilised and modified the southeastern LM for maize-based agriculture. A modelling approach is ideal for addressing this question given the limited data available for this culture. Agent-based techniques are particularly suitable because they treat system characteristics, such as anthropogenic landscape modification, as the emergent product of choices made by individual decision-makers (Railsback & Grimm 2019), enabling human behaviour to be explicitly modelled. Our model is designed to function as a ‘virtual laboratory’ (Magliocca & Ellis 2016), capable of exploring how the southeastern LM might have been utilised by the Casarabe Culture across a range of plausible ‘What if?’ scenarios (Cegielski & Rogers 2016; Davis 2016). It explicitly focuses upon both the quantity and spatial distribution of land cleared of vegetation and converted to maize monoculture (Lombardo et al. 2025). Although the Casarabe Culture could have also grown maize in other ways (e.g., through polyculture agroforestry), we make this assumption for computational simplicity.

We first describe our model, which integrates archaeological, ecological, ethnographic, and topographic data to produce a recreation of the southeastern LM within a simplified, gridded landscape. On this landscape, a representation of the Casarabe Culture is generated as an aggregation of agents, each representing a nuclear household unit. These agents are the main subjects of our experiments, and function as the primary drivers of landscape modification within the model. Following this, we discuss a number of sensitivity experiments that were conducted to assess how much of the virtual landscape these agents modify for maize-based agriculture under a variety of parameter assumptions. In doing so, we also identify which of the model’s parameters most greatly influence the amount of modified land. Finally, we alter the criteria used by these households when selecting new farming sites to explore how changing their preferences impacts upon the spatial distribution of modified land. The outputs generated by these experiments not only help to elucidate how the environmental impact of the Casarabe Culture may have manifested on this landscape, but also provide potential underlying motivations driving its transformation.

Model Overview

Purpose, environment, and initialisation

The purpose of our agent-based model, MoundSim LandUse, is to simulate the land claimed and modified by the Casarabe Culture for maize-based agriculture under various plausible ‘What if?’ scenarios (Cegielski & Rogers 2016). As little is known about this culture’s agricultural practices, we instead take an exploratory approach by encoding human behaviour as a set of simple, logical rules, which follow the principles of bounded rationality (Gigerenzer & Selten 2001; Simon 1955). We parameterise this behaviour using ethnographic data sourced from modern indigenous groups living both within the LM (Holmberg 1969; Ringhofer 2010) and beyond (Binford 2001). While there are clear limitations to such an approach (Roosevelt 1989), it enables us to conduct a preliminary exploration of how the Casarabe Culture utilised the landscape in lieu of obtaining further empirical data. MoundSim LandUse has been developed in NetLogo 6.3.0 (Wilensky 1999), and a full ODD (Overview, Design + Details) description is available within the Supplementary Information (Grimm et al. 2006, 2010; Müller et al. 2013).

The model landscape consists of a 359 \(\times\) 416 grid of land patches that together reproduce a 1500 \(km^2\) quadrant of the southeastern LM. Upon initialisation, the user can select between one of four different quadrants to model within the 4500 \(km^2\) region where the Casarabe Culture’s earthworks have been mapped in detail (Lombardo & Prümers 2010). Each land patch represents a single hectare, within the known range of modern indigenous field sizes (0.3 - 2.5 ha; Beckerman 1987; Denevan 2001). These patches possess variables to denote their primary land cover type, and elevation. They also possess a binary productivity score, determined by whether they contain the fertile sediments deposited as a vast alluvial lobe in this region by a climate-driven avulsion of the white-water (mineral-rich) Rio Grande during the late Holocene (Lombardo et al. 2012). These variables are parameterised by raster datasets that are imported when the model is initialised. In our experiments, we concentrate on the northeastern modelled quadrant, an area extensively covered by fertile alluvial sediment and where the mounds are most densely packed.

Inhabiting this virtual landscape are household agents intended to represent nuclear family units of two adults and three children. This size was selected to simplify the complex family dynamics associated with Amazonian indigenous groups (Binford 2001). As the large size and lengthy occupation period of the earthworks indicates the Casarabe Culture was sedentary (Jaimes Betancourt 2012, 2015; Prümers et al. 2022), we assume these agents permanently reside atop mound settlements, which are encoded as a second agent-type to which the households are linked. Upon initialisation, settlement agents spawn at locations where mounds have been identified on the real landscape (Lombardo & Prümers 2010), each possessing a user-defined number of households. As the earthworks are interconnected (Prümers et al. 2022), we also assume that all settlement agents are occupied contemporaneously. For simplicity, we assume that each settlement agent spawns with the same number of attached households, and that these households remain attached to their allocated settlement throughout the simulation. Each timestep within the model equates to one year, with simulations running for 1000 years to match the current known occupation duration (Jaimes Betancourt 2012, 2015).

Household decision-making

Claiming/transforming land

The scale and interconnectedness of the Casarabe Culture’s earthworks implies that they operated at a supra-communal political level (Lombardo & Prümers 2010; Prümers et al. 2022). However, in MoundSim LandUse, human decision-making is abstracted to the household level, as there is little information regarding how such a political structure would have affected their agricultural practices. Household agent behaviour centres on obtaining five resources commonly sought by Amazonian indigenous groups: maize; foraged tree crops; fuelwood; palm leaves; and animal protein. Our agents are satisficers (Simon 1955), making decisions to claim, cultivate, and extract resources from the landscape to meet their requirements. The number of households cannot increase during a simulation but can, depending on user preference, decrease if they fail to obtain sufficient quantities of resources. In a recent article (Hirst et al. 2025b), we estimate that the Casarabe Culture reached a population of between 10,000 and 100,000 people and our experiments here assume a population size within this range. While the Casarabe Culture’s population size almost certainly fluctuated over time, making this assumption allows us to incorporate regional population size into our experiments as an input.

The primary way for household agents to obtain resources is by claiming and cultivating patches of land. For simplicity, only one crop exploited by the Casarabe Culture is incorporated into MoundSim LandUse; maize was chosen due to it being the staple crop utilised by the Casarabe Culture (Hermenegildo et al. 2024; Lombardo et al. 2025). Any claimed land patch is assumed to be converted to maize monoculture (Lombardo et al. 2025) for simplicity, producing maize for a set number of timesteps, before being allowed to lay fallow. Our model follows the cultivation system of the Tsimane indigenous group (Huanca 1999; Piland 1991). The Tsimane’s land-use practices may differ from those of the Casarabe Culture (Roosevelt 1989). However, as the specifics of the Casarabe Culture’s land requisition system remain unknown, the Tsimane’s provides the most appropriate system to project backwards, given that they live in the western LM. In this system, all fallow patches remain the property of the cultivating household until they can no longer be distinguished from the natural vegetation, encoded in MoundSim LandUse as two regeneration variables (discussed below). Moreover, we assume that when a forest patch is cultivated, agents practice swidden fallow management, planting and protecting useful forest species (Denevan 2001). This produces forest resources to which the owner household enjoys exclusive access rights.

Households claim new land patches depending upon whether they expect to produce sufficient resources from their existing territory. This assessment is conducted with imperfect information; households can accurately assess the spatial average of land productivity, but cannot account for interannual variability. For example, their expected maize supply (\(M_{es}\)) is calculated as the number of cropland patches within their household territory (\(n_{c}\)), multiplied by the overall average maize yield per hectare of cropland (\(M_{c}\)). This value is further multiplied by 0.85 due to the expected yield loss from pests (Ringhofer 2010):

| \[ M_{es} = 0.85 \times n_{c} \times M_{c}\] | \[(1)\] |

The resulting estimate is compared with demand to assess whether the household expects to experience a resource shortfall. Each household will always attempt to produce enough maize from their territory, but the user can also set household agents to consider their production of tree crops, fuelwood, and palm leaves. Each household can convert only 1 ha of forest or up to 2 ha of savanna per timestep. Although modern small-scale farmers can clear up to 3 ha of forest annually (Fearnside 1980, 2006), the Casarabe Culture’s reliance on stone tools would have made this task more arduous (Denevan 1992a).

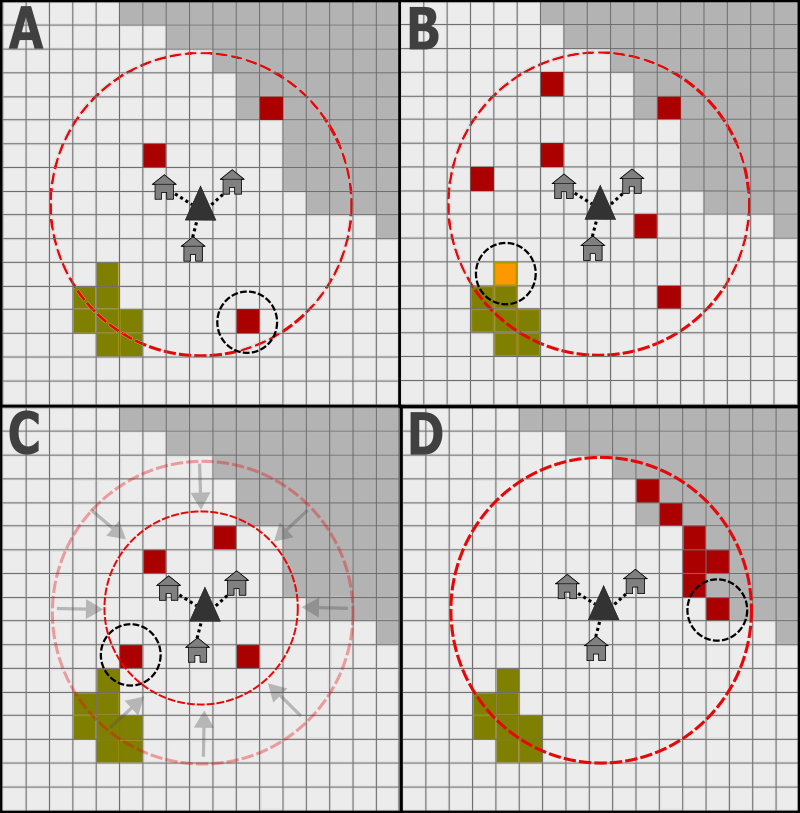

If a resource shortfall is expected, households first determine whether to remobilise land they already own, or instead to claim a new patch for agriculture. This decision is managed stochastically, with the chance of recultivation dependent on a user-defined probability. If they choose to claim new land, households will optimise their selection based on the limited information available. They can claim any unowned patch of land within a user-defined radius of their home settlement, excluding all areas of open water and land designated as fallow. In our experiments, this radius is set to 3 \(km\) to match modern ethnographic observations (Apaza et al. 2002; Ringhofer 2010). Additionally, only a random subset of these patches is provided to them for consideration (Figure 1). The size of this subset is also user-defined, enabling the modeller to explore how the land modified by households responds to changes in the quantity of information provided. New cultivation sites can be selected in multiple ways:

- A null model that forces households to select one candidate patch randomly.

- Patches nearer to causeways and canals identified on the real landscape are preferentially selected. This is calculated using imported datasets for each earthwork type (Lombardo & Prümers 2010).

- Households select patches based on environmental characteristics they find ‘desirable’.

In the latter approach, households calculate utility scores (\(U_{sc}\)) for each candidate patch:

| \[ U_{sc} = P_{sc} + E_{sc} + Fl_{sc} - D_{sc} - Df_{sc} + A_{sc}\] | \[(2)\] |

Each component of this utility score (productivity (\(P_{sc}\)); elevation (\(E_{sc}\)); flooding (\(Fl_{sc}\)); distance (\(D_{sc}\)); clearance difficulty (\(Df_{sc}\)); and aggregation (\(A_{sc}\))) is calculated independently. They can also be weighted by the user to influence how much they contribute to overall utility (\(P_{w}\), \(E_{w}\), \(Fl_{w}\), \(D_{w}\), \(Df_{w}\), and \(A_{w}\)). If weighted equally, each component contributes the same score to the overall value.

A patch is considered more productive if it contains the fertile alluvial sediments deposited in the southeastern LM during the mid-late Holocene (Lombardo et al. 2012). The productivity component (\(P_{sc}\)) is therefore binary, with patches containing this sediment possessing a score (\(P\)) of 1 and those in other areas possessing a value of 0:

| \[ P_{sc} = P_{w} \times (100 \times P)\] | \[(3)\] |

The second component, elevation (\(E_{sc}\)), ascribes higher utility to patches less likely to experience seasonal flooding. This is based upon an imported elevation dataset that has been modified to remove the shallow (0.1 mm \(m^{-1}\)) South-North gradient recorded across the LM (Lombardo et al. 2012). No additional utility is gained from patches possessing an elevation higher than the lowest mound on the landscape (+2.04 m) because settlements do not regularly flood, making flood risk sufficiently low above this height. Additionally, no further utility is gained below -2 m, as we assume the lowest 5% of patches on the landscape are considered swamp and thus undesirable for agriculture. Patches therefore receive maximum utility at +2.04 m, which reduces linearly across a 4.04 m range:

| \[ E_{sc} = E_{w} \times max(0, min(100, (100 \times (E + 2) / 4.04)))\] | \[(4)\] |

The flooding component (\(Fl_{sc}\)) represents the antithesis of the elevation component, ascribing utility to patches in areas more likely to flood. Notwithstanding Lombardo et al. (2025), little is known about the season(s) in which the Casarabe Culture farmed and, if they cultivated during the dry season, they may have prioritised cultivating close to low-lying water sources. Utility is maximised at -2 m elevation and decreases as height increases, providing no utility beyond +2.04 m:

| \[ Fl_{sc} = Fl_{w} \times 100 - max(0, min(100, (100 \times (E + 2) / 4.04)))\] | \[(5)\] |

The distance (\(D_{sc}\)) component reduces utility further from the home settlement of the household agent. This applies relative to the user-defined radius (\(R_{a}\)) within which households can cultivate, decreasing utility in a non-linear manner with increased distance:

| \[ D_{sc} = D_{w} \times 100 \times (\frac{D^{2}}{R_{a}^{2}})\] | \[(6)\] |

The difficulty component (\(Df_{sc}\)) provides utility to patches that are easier to clear of vegetation. Each patch possesses a vegetation score that reflects the amount of vegetation on the patch, with the maximum value associated with the vegetation score of fully mature/regenerated forest (\(V_{fmax}\)):

| \[ Df_{sc} = Df_{w} \times 100 \times (\frac{V}{V_{fmax}})\] | \[(7)\] |

Finally, the aggregation component (\(A_{sc}\)) increases utility if the patch borders land that is already being actively used (Border), either as managed cropland or having been recently fallowed. The deciding household does not need to be the owner of the neighbouring land, neither does it need to reside within the same settlement as the household that owns it:

| \[ A_{sc} = A_{w} \times (\text{Border} \rightarrow 100,\, \lnot\text{Border} \rightarrow 0)\] | \[(8)\] |

After calculating and combining these components, households select the patch with the highest utility. If multiple optimal patches are found, one is selected at random.

Alternative methods of resource extraction

Should a household fail to produce sufficient quantities of each resource, they can mitigate the shortfall in two ways. Firstly, resources can be communally shared among households from the same settlement. This is coded as a form of generalised reciprocity, where households with surplus resources assist under the expectation similar help would be given if they experienced a shortfall (Romanowska et al. 2021; Sahlins 1972). Only maize, fuelwood, and animal protein can be shared in this way. The spoils of successful hunts are commonly shared by indigenous groups (Good 1987), and maize is typically stored and consumed on an annual basis (Piland 1991). Palm leaves and tree crops are excluded because they can be rapidly sourced and consumed on demand for a variety of purposes (Holmberg 1969; Smith 2015). We further assume none of these resources can be stored interannually due to their rapid degradation in Amazonian environments (Denevan 1996).

Households can also extract resources from unclaimed forested patches in the area controlled by their settlement, defined as the land within daily walking distance (7 \(km\); Beckerman 1987; Binford 2001) that is closer to it than to any other settlement on the landscape. This produces a division similar to the Thiessen’s polygons (Hodder & Orton 1976) analysis of the Casarabe Culture conducted by Lombardo & Prümers (2010). While we recognise that the canals and causeways of the southeastern LM can reach up to 17 \(km\), travelling these distances typically involves crossing land more readily accessible to multiple other mounds. All resources except for maize are obtainable via the extraction process, as this crop is domesticated and cannot survive without human intervention.

Resource shortages and agent death

Similar to the Artificial Anasazi model (Axtell et al. 2002; Dean et al. 2000), the ‘death’ of household agents in MoundSim LandUse refers to the point at which a family unit ceases to exist. Over time, agents naturally dissolve and are immediately replaced by new ones as we assume children to grow up and start their own families. However, households can also dissolve if they fail to obtain sufficient quantities of each resource through the methods described above. The user can select whether any households experiencing a resource shortfall are either marked as stressed or dissolve. The former is a variable which tracks whether households are experiencing a shortage, but otherwise does nothing. With the latter, households abandon their territory and dissolve without being replaced. If a settlement loses all its member households due to this process, it becomes abandoned and loses control of its territory, which can then be claimed by other active settlements.

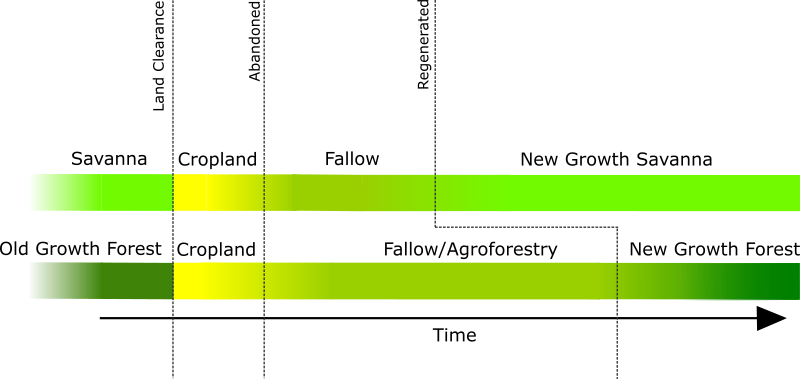

Vegetation succession

Within MoundSim LandUse, vegetation succession is managed differently depending upon whether a patch has the potential to become forested (Figure 3). This is based upon the land cover dataset imported into the model, which defines whether patches are initially categorised as ‘natural’ areas of ‘Water’, ‘Savanna’, or ‘Old Growth Forest’. For the purposes of this study, we define ‘natural’ and ‘old growth’ as land that has not been modified by the Casarabe Culture. There is clear evidence (Lombardo et al. 2013) that humans have been utilising natural resources in the southeastern LM to varying degrees for millennia prior to the Casarabe Culture’s arrival. However, our sole goal is to model the extent of the Casarabe Culture’s land use. As formerly forested land is abandoned, it is assumed to undergo standard secondary succession (Finegan 1984; Peña-Claros 2003), during which woody taxa rapidly establish, before maturing over longer periods of time (Rozendaal et al. 2019). This is simplified within the model as a vegetation score that increases over time on a logistic scale, until it becomes indistinguishable as ‘New Growth Forest’. Savanna forgoes woody succession, rapidly regenerating into ‘New Growth Savanna’.

Simulation experiments

We conducted two interrelated experiments on MoundSim LandUse to explore the number and spatial distribution of land patches converted by households across a range of different parameter assumptions: (i) sensitivity analysis, and (ii) agent preference. Both of these experiments were conducted on the northeastern quadrant of our study area (Figure 1). The parameter values selected for these experiments are displayed in Table 1. A full list of constants used in both experiments can be found within the Supplementary Information.

| Parameter | Medium | High | Low | Metric | Deviation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 150 | 200 | 100 | people per settlement | ±33.33% | Binford (2001) |

| Agricultural Radius | 3 | 4 | 2 | \(km\) | ±33.33% | Piland (1991); Apaza et al. (2002) |

| Probability of Reactivation | 67 | 44.7 | 89.3 | % | ±33.33% | Ringhofer (2010) |

| % Patches considered | 3.6 | 4.8 | 2.4 | % | ±33.33% | |

| Overproduction | 15 | 20 | 10 | % | ±33.33% | |

| Maize Productivity | 1500 | 2000 | 1000 | kg ha\(^{-1}\) | ±33.33% | Various (See Appendices) |

| Crop Cycle length | 3 | 4 | 2 | years | ±33.33% | Staver (1989); Beckerman (1987) |

| Minimum Fallow period | 6 | 8 | 4 | years | ±33.33% | Huanca (1999) |

| Savanna Regeneration Time | 10 | 13 | 7 | years | ±30% | |

| Forest Regeneration Time | 40 | 28 | 52 | years | ±30% | Huanca (1999) |

| Farm Size | 1 | ha | Denevan (2001); Beckerman (1987) | |||

| Simulation Length | 1000 | years | Jaimes Betancourt (2012, 2015) | |||

Sensitivity analysis

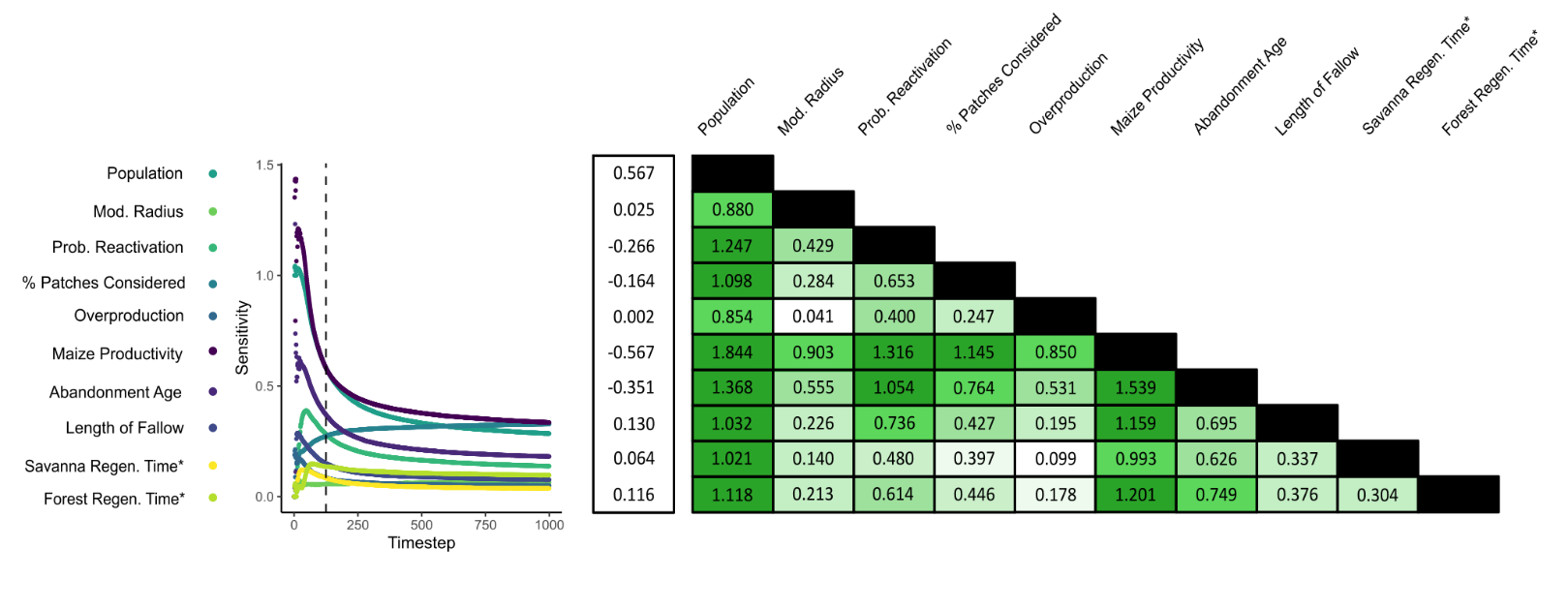

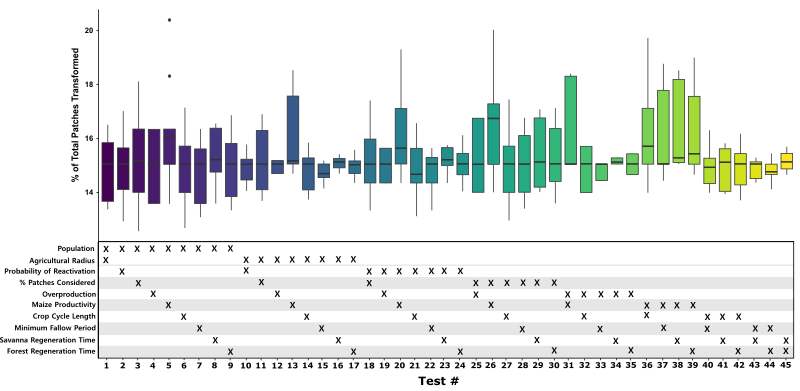

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to observe how different parameter assumptions affected the amount of land modified by household agents. This experiment consisted of 45 tests, within each of which two parameters were varied between ‘low’, ‘medium’, and ‘high’ values. Each test therefore contained nine permutations, with all non-varying parameters set to their respective medium values. 25 simulation runs were performed for each permutation, resulting in a total of 11,250 runs being completed. During the experiment, households could modify both the forest and open savanna, possessing no environmental preferences other than to select land patches closer to their home settlement (\(D_{sc}\)).

During each timestep (\(t\)), a sensitivity estimate (\(S_{t}\)) was calculated for each varying parameter. First, the total number of patches modified by households (\(n_{pm,t}\)) was calculated as the sum of cropland (\(n_{c,t}\)), agroforestry (\(n_{af,t}\)), fallowed land (\(n_{fa,t}\)), regenerated forest (\(n_{fr,t}\)), and regenerated savanna (\(n_{sr,t}\)) patches:

| \[ n_{pm,t} = n_{c,t} + n_{af,t} + n_{fa,t} + n_{fr,t} + n_{sr,t}\] | \[(9)\] |

A mean value (\(\mu n_{pm,t}\)) was then calculated for each permutation. Sensitivity estimates were derived by relating the amount of modified land when parameters were high (\(x^{+}\)) and low (\(x^{-}\)) compared to the extent when medium (\(x\)) values were selected:

| \[ S_{t} = \frac{((\mu n_{pm,t,x^{+}} - \mu n_{pm,t,x^{-}}) / \mu n_{pm,t})} {((x^{+} - x^{-}) / x)}\] | \[(10)\] |

In both sensitivity estimates, values farther from zero indicate higher sensitivity to changes in the selected input parameter(s).

Agent preferences

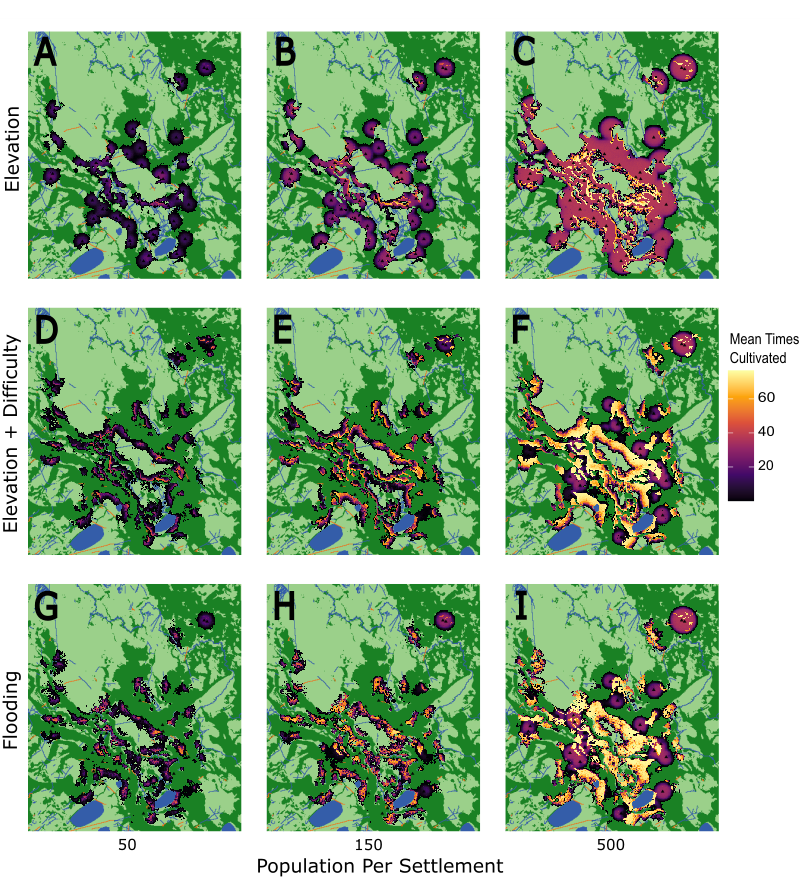

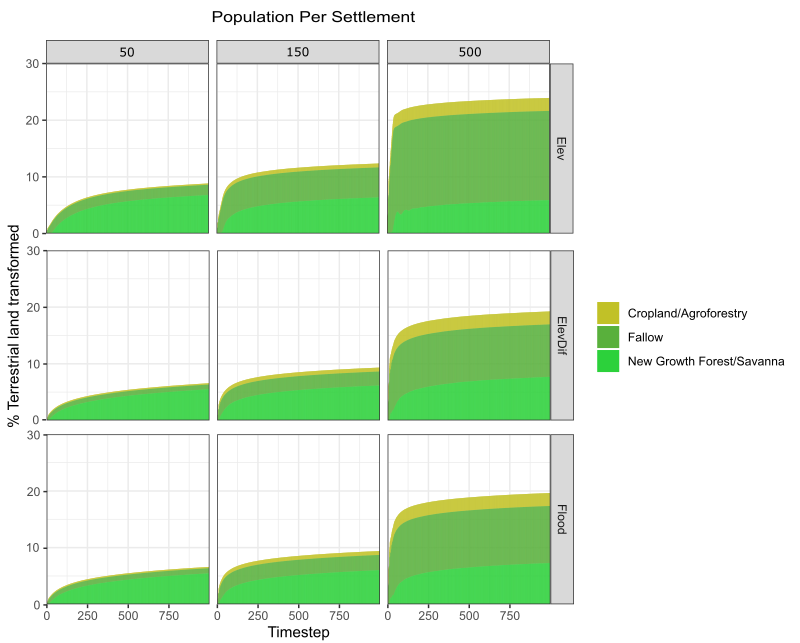

We conducted a second experiment to explore the spatial distribution of anthropogenically modified land when different environmental characteristics were prioritised by household agents. During the test, household preferences were set to one of three ‘preference pathways’ (Table 2). In the first, ‘Elev’, agents were assumed to prefer cultivating land at higher elevation to avoid the detrimental effects of flooding. In the second, ‘ElevDif’, households were still assumed to prefer higher elevation, but this was outweighed by the difficulty associated with clearing more heavily vegetated land. Finally, in the ‘Flood’ pathway, agents were assumed to prefer cultivating at low elevation to take advantage of low-lying water stores.

Irrespective of preference pathway, households preferred cultivating closer to their home settlement and, if possible, cultivating next to land already being managed. Each pathway was tested at three different population levels, set to 50, 150, and 500 people settlement\(^{-1}\). This equates to total populations of 2250, 6750, and 22,500 within the studied quadrant, enabling us to examine the impact of population across multiple orders of magnitude. In total, the experiment consisted of nine tests, each of which was run 25 times (225 runs total). Aside from population as described above, medium parameter values were used for all runs.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Elev | ElevDif | Flood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation Bonus | \(E_w\) | Utility gained from patches at higher elevation | 1 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Flooding Bonus | \(Fl_w\) | Utility gained from patches at lower elevation | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Distance Cost | \(D_w\) | Utility gained from patches closer to settlement | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Difficulty Cost | \(Df_w\) | Utility lost from patches more difficult to clear of vegetation | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Aggregation Bonus | \(A_w\) | Utility gained from patches adjacent to other managed land | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Results

Extent of transformed land

During sensitivity experiments, household agents were observed to modify only localised portions of the landscape for maize-based agriculture (Figure 4A). The number of modified patches during each simulation run varied between 18,767 and 30,458 (equivalent to \(187.7 - 304.6 km^{2}\)), reaching between 20,000 and 25,000 during most simulations. This collectively represents between 12.9 and 20.9% of the total terrestrial (non-water) land surface in the modelled quadrant. However, only a subset of this modified area (21.00 - 58.51%) is actively managed as cropland or recently fallowed land at any one time. The remainder was abandoned by households for sufficient time to regenerate into either New Growth Forest or Savanna.

The land modified by household agents is unevenly distributed in space (Figure 4C), concentrated in areas where settlements are more densely packed. For example, at Loma Alta de Casarabe (red box) a mound settlement surrounded by five other sites, up to 90% of the land within a 3-\(km\) radius is modified under baseline parameter assumptions. By contrast, the proportion is much lower where settlements are more isolated, sometimes barely exceeding 26%. Despite this spatial variation, however, no settlement exploited every patch within the baseline 3-\(km\) modifiable radius, indicating our imposed limit does not unduly constrain household agent behaviour. It should be noted that while settlements situated adjacent to the quadrant boundaries typically record lower proportions of anthropogenically modified land, these patches may also fall into the territory of settlements located outside of the modelled quadrant. For this reason, any estimates in these areas should be treated as conservative.

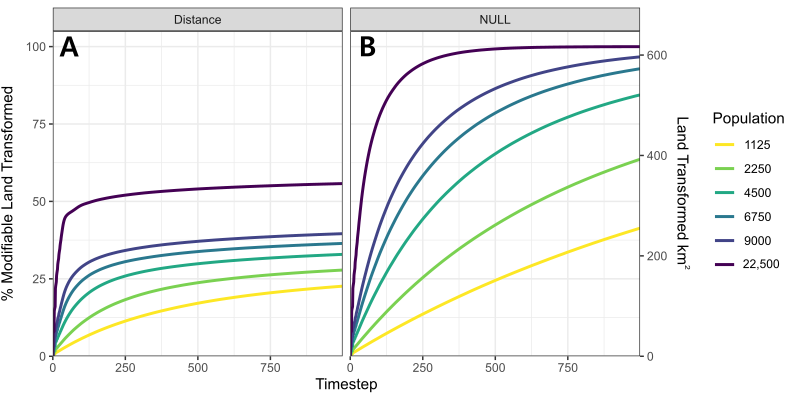

The pattern of land utilisation by household agents is characterised by a rapid rate of old growth conversion during the first 250 timesteps, followed by negligible increases thereafter. During the initial stage, modification rates are commonly shown to reach 4 \(km^{2} \; year^{-1}\) (400 patches, Figure 4B). Yet they rarely exceed a few dozen patches after 250 timesteps, deteriorating further to 0.024 \(km^{2} \; year^{-1}\) by the end of each simulation. This pattern is driven by households increasingly choosing to cultivate land that has already been modified. This behaviour is best observed in Figure 5, which displays the results of a separate experiment to compare the number of patches modified when (A) households preferentially select patches closer to their home settlement, versus (B) where households employ the null selection approach to select sites randomly. Under the latter strategy, households are shown to be capable of modifying the vast majority of land within the modifiable radius unless the regional population is extremely small (1125 people, 25 people settlement\(^{-1}\)). Conversely, fewer patches are modified when households choose to prioritise ‘optimal’ environmental characteristics, in this case proximity to their home settlement. The most valuable of these patches are often immediately reclaimed as soon as they become available. After 250 years, the total number of modified patches is sufficient to enable households to indefinitely alternate between them without needing to further extend into areas of old growth.

This prioritisation of desirable land has implications for the proportion of modified land under active management, which is positively correlated to the total number of modified patches (Figure S1). This is caused by agents systematically recultivating desirable patches as soon as they become available. Under higher levels of resource demand, agents are shown to prefer intensifying cultivation on desirable land over further extending into unused parts of their territory.

Sensitivity analysis

Our sensitivity experiments show that the number of patches modified by household agents responds insensitively to changes in baseline parameter assumptions. A 66.67% change in any one baseline parameter typically generated a shift of between 1.5 and 3% in the number of modified patches (\(21.8 - 43.6 km^{2}\); Figure 6). However, this responsiveness substantially varies depending on the parameter being altered. The two parameters which provoke the greatest response are regional population size and maize productivity, each generating 4-5% shifts in the total percentage of modified land. This is unsurprising given that both directly affect the balance between resource demand and supply; the former modifies total agent demand, while the latter influences the landscape’s ability to meet these requirements. Nonetheless, both still produce less-than-proportionate responses to the initial parameter change, driven by the preference to intensify cultivation in response to increased resource demand. Other parameters within the model are even less influential. For some, this is expected; the size of agricultural radius should hold little influence on the amount of modified land as households never come close to fully exploiting the land made available to them. In others, such as the rate at which vegetation regenerates, the reason is less clear. Multiple potential factors may explain this insensitive response, including the availability of land relative to demand reducing household reliance on regenerating patches, and the imperfect information used when new cultivation sites are selected.

The amount of land modified by households becomes less responsive to changes in most parameters over the course of each simulation run. This is driven by the general reduction in old growth being claimed over time. After 250 timesteps, sufficient desirable land has been cultivated to allow agents to indefinitely survive without needing to claim additional areas of old growth. The only parameter which deviates from this trend is the quantity of information provided to household agents when selecting new cultivation sites. Households will occasionally cultivate old growth due to the imperfect information provided to them; unable to assess every available patch, households sometimes cultivate in suboptimal locations despite more desirable land being accessible. Even after the equilibrium at 250 timesteps becomes established, the number of modified patches can still increase due to these suboptimal selections. Thus, unlike other parameters, the model sensitivity to agent knowledge increases over time. By the end of each simulation, sufficient suboptimal decisions have accumulated to make this one of the most influential parameters, rivalling population size and maize productivity.

This experiment also emphasises the importance of our choice to model the process of claiming and converting land at hectare-scale spatial resolution. The decision made by households when claiming new land is whether their expected shortfall warrants cultivating an additional hectare of farmland (Figure S1). Thus, changing baseline parameter values will only generate a response if households choose to cultivate either more or fewer land patches. For example, while reducing maize productivity increases the quantity of modified land, increasing it does not produce an equivalent response (Figure 7). Maize productivity is an influential parameter, but our medium estimates already enable households to survive by cultivating maize on just one hectare of land. Even if productivity were to increase further, households are still obliged to cultivate one hectare because the model operates at this resolution.

Spatial distribution of transformed land

The outputs of our spatial distribution experiments enable us to generate spatially explicit maps of the land modified by households when they are assigned specific environmental preferences (Figure 8). These maps corroborate the results of our sensitivity experiments, showing that a substantial proportion of the landscape remains untouched even when the experiment assumes a large regional population (500 people settlement\(^{-1}\)). The land modified by households from the same settlement is typically concentrated into localities that possess optimal environmental characteristics. Throughout each simulation, all patches within these optimal localities are cultivated at least once. Since the mound settlements are located in such close proximity to one another, these localities often overlap. However, in most cases there remains sufficient forest and savanna available for the members of each settlement to cultivate in one of these ecosystems without needing to encroach upon the other. As shown under the ‘Elev’ pathway (Figure 8 A-C), most households are able to cultivate in forested areas without needing to expand into the savannas even when populations are dense. Similarly, the forest is rarely encroached upon in both the ‘ElevDif’ (Figure 8 D-F) and ‘Flood’ pathways (Figure 8 G-I). There are, however, exceptions to this rule, where settlements are particularly closely spaced or where limited optimal land is available. For example, deforestation still occurs under both the ‘ElevDif’ and ‘Flood’ pathways if agent populations are high or there is limited open ground within the 3-\(km\) modifiable radius imposed upon households.

The extent to which the patches within a locality are exploited depends upon the demand for land. Under baseline parameter assumptions, any claimed land is expected to be modified between 4 and 16 times during a simulation run (Median: 16.16, 4.48, and 5.33 times for the ‘Elev’, ‘ElevDif’, and ‘Flood’ pathways respectively), equating to each patch being cultivated once every 62 to 250 years. This decreases to just a few conversions when low regional populations are assumed (50 people settlement\(^{-1}\); Median: 3.68, 1.00, and 1.28 times), driven by the greater availability of desirable land relative to collective household demands. Under this scenario, the local landscape is used extensively, but less intensively, where much of the modified land receives sufficient time to fully regenerate (Figure 9). In contrast, high resource demands and the preference for intensification mean that desirable patches are often cultivated over 25 times per simulation when dense regional populations are assumed (500 people settlement\(^{-1}\); Median: 34.80, 27.88, and 28.96 times). This exploitation is particularly acute under the ‘Elev’ pathway given the longer regeneration period for forested land, which reduces the availability of optimal land at any one time. As a result, households are forced to spread their cultivation more evenly as opposed to strategies which favour the open savanna, where rapid regeneration leads to a more uneven distribution. This is exemplified in Figure 9 as, while all preference pathways show higher proportions of actively managed land under a dense regional population, the increase is particularly severe for the ‘Elev’ pathway. However, even under dense populations, the median number of times each patch is cultivated still falls far below the number expected when the land is fully exploited. The most desirable patches on the model landscape at 500 people settlement\(^{-1}\) were cultivated almost twice as frequently as the median (Max: 76.24, 76.68, and 76.56 times).

Discussion

Each of the parameter combinations simulated in the above experiments represents a ‘What if?’ scenario of how the Casarabe Culture could have modified the southeastern LM for maize-based agriculture (Cegielski & Rogers 2016; Premo 2007). Using these results as a guide, we now develop multiple hypotheses regarding how this culture utilised the real landscape.

Local versus regional landscape domestication

The purpose of our sensitivity experiments was to capture how the cumulative number of patches modified by households varies across a range of behavioural assumptions. However, despite these differing assumptions, households only modified between 12.9 and 20.9% of the terrestrial land surface (\(187.7 - 304.6 km^{2}\)) after 1000 timesteps. Moreover, only approximately one third of this land (mean: 34.6%) was actively managed as cropland or fallow at any time (\(65 - 105.4 km^{2}\)). These results directly challenge prior studies which claim the Casarabe Culture was responsible for large-scale deforestation in the southeastern LM (Erickson 2006; Erickson & Balée 2006), and instead support palaeoecological evidence in suggesting their environmental impact upon forest ecosystems was far more localised (Whitney et al. 2013). We cannot explain these results with the 3-\(km\) limit imposed on the behaviour of our household agents because (i) no settlement mobilised every patch within this radius and (ii) even mobilised patches could have been exploited more intensively. The hectare-sized farms cultivated by our agents fall within the 0.3 - 2.5 ha size range of modern indigenous fields (Beckerman 1987; Denevan 2001), making them reasonable approximations for the land mobilised by small-scale farmers. Additionally, while MoundSim LandUse was found to be sensitive to population size, we incorporated high population density scenarios as part of our experiments. Our baseline assumption of 150 people settlement\(^{-1}\) is over twice the pre-Columbian population estimated for this region by Denevan (1992b) and Denevan (2003). Our spatial distribution experiments also included the tentative 500 people settlement\(^{-1}\) proposed by Clark Erickson for the medium-sized mound at Ibibate (Mann 2000), and land remained available even under this assumption. Based on these results, we can therefore reinforce and extend the hypothesis originally proposed by Whitney et al. (2013) that the Casarabe Culture had only local-scale impacts on the forests of the southeastern LM.

A common conceptual framework in studies of historical ecology, such as the one undertaken at Ibibate (Erickson & Balée 2006), considers the landscape to be a palimpsest upon which the cumulative impacts of human activity are recorded (Balee 2006, 2013). However, these studies often understate the capacity for humans to overwrite parts of this palimpsest that they have already altered. This capacity is demonstrated in our results through the rapidly diminishing rate at which areas of old growth vegetation are converted for maize agriculture during each simulation run. Multiple factors that contribute to this pattern within MoundSim LandUse are also relevant for the real Casarabe Culture, the first of which being the sedentary nature of our agents. When testing an agent-based model of the indigenous Piaroa of the Upper Orinoco, Riris (2018) identified mobility as an important driver of landscape modification, as humans were continually exposed to new, previously uncultivated land. The Casarabe Culture represents the opposite of this scenario, whereby their sedentary nature is evident through the size and spatial complexity of their earthworks (Lombardo & Prümers 2010; Prümers et al. 2022). In the model, sedentism leads generations of household agents to repeatedly interact with the same subset of land patches, a pattern further reinforced by the competition from nearby settlements. Human intervention might enrich the patches with useful species, potentially dissuading their future clearance (Balee 1989; Roosevelt 2013), but this relies on these species being identifiable, and the land being specifically valued for their presence. Regarding the former, although tropical forests may take centuries to fully recover from disturbance (Poorter et al. 2021; Rozendaal et al. 2019), indigenous communities may consider the land to be available and suitable for cultivation within decades (e.g., the Tsimane; Huanca 1999). Regarding the latter, the patch selection process systematically favours selecting previously cultivated patches. Land claimed early during each simulation run is chosen by household agents because of its advantageous characteristics compared with other patches, many of which are immutable (e.g., being located at higher elevation when agents seek to avoid seasonal flooding; Hanagarth (1993)). In some cases, cultivating secondary vegetation is even preferred by indigenous groups due to the ease of clearance (Ringhofer 2010).

In MoundSim LandUse, these factors collectively drive households to repeatedly overwrite the same parts of the landscape, alternating between previously cultivated patches. Even if collective household resource demands were to increase, such as through population growth, our sensitivity analysis indicates that they would prioritise intensifying cultivation in desirable areas. While the overall percentage of modified land only varies between 12.9 and 20.9% during our experiments, the amount of that land being actively managed ranges from 20.99 to 58.51%. As such, we hypothesise that the areas that were cultivated by the Casarabe Culture were intensively and repeatedly modified. This hypothesis is relevant to both archaeologists and palaeoecologists because, if correct, these areas should display clear signs of intensive anthropogenic modification. This could include the abundance and variety of economically useful species, even if many are only incipiently domesticated and thus provide little definitive evidence of human activity (Balee 1989; Clement 1999).

Forest versus Savanna: Spatial distribution of modified land

Approximately 44.3% of the terrestrial land surface in the northeastern quadrant of our study area is covered by forest (with savanna covering approximately 55.7%). As only between 4.5 and 7.2% of this terrestrial land is actively managed by households during sensitivity experiments, our results suggest that the Casarabe Culture could have cultivated maize in the open savannas (Lombardo et al. 2025) without needing to farm it in the nearby forests. Even in our spatial distribution experiments, which assumed dense regional populations (500 people settlement\(^{-1}\)), forest incursions only occurred where the local availability of savanna was scarce. There are multiple reasons why cultivating the open savannas would have been logical. While maize can be incorporated into many farming strategies (Denevan 2001; Levis et al. 2018), some degree of deforestation would be necessary on forested land because of the crop’s shade intolerance (Gao et al. 2020). Yet, clearing even small areas would have represented an arduous task for the Casarabe Culture. The best technology available to them, stone tools, is highly inefficient (Denevan 1992a, 2001). These tools are also extremely rare in the southeastern LM (Prümers 2015), which would have forced them to rely upon suboptimal improvisations made from teeth, bone, and palm wood (Denevan 2001). Moreover, preserving local forest cover would also mean retaining access to numerous forest resources that the Casarabe Culture are known to have exploited, e.g., palm fruit and game (Bruno 2010; von den Driesch & Hutterer 2011). In MoundSim LandUse, we attempted to compromise by following the approach of modern Amazonian indigenous groups (Clement 1999; Huanca 1999; Posey 1998); that if maize was grown in the forests, the Casarabe Culture would maximise their energy investment by using the same land to grow other useful species (Denevan 2001). However, our model outputs imply that this decision should be reviewed; there would be no need to cultivate maize in the forests if a sufficient amount could be grown in the open savannas (Lombardo et al. 2025). Moreover, numerous techniques can be used to enrich forest ecosystems without the need for forest clearance (Levis et al. 2018). As such, we hypothesise that since the Casarabe Culture cultivated maize in the open savannas, the practices of cereal-based agriculture and agroforestry were likely divorced from one another spatially. These results raise an important question: if the modern species composition of these forests (Erickson & Balée 2006; Townsend 1995, 2000) does reflect a legacy of anthropic modification, what forms of landscape intervention did the Casarabe Culture practice in these areas to produce them? Further work to record the species composition of these forests, in relation to their spatial distribution (e.g., distance from the artificial mounds) could help to further elucidate how, and to what extent, the Casarabe Culture shaped their biodiversity.

Our spatial distribution experiments highlight the non-random spatial distribution of settlements across our study area. Despite the size and spatial complexity of the Casarabe Culture’s mounds suggesting they were built by a large, socio-politically complex society (Prümers et al. 2022), they are very closely-spaced. The average distance between these features is just 2.7 \(km\), and the closest are situated less than 500 m apart (Lombardo & Prümers 2010). For comparison, even the small indigenous communities living in Amazonia today regularly travel up to 7 \(km\) from their home settlement (Beckerman 1987). Yet, previous archaeological research indicates this close spacing had negligible effect on the contemporaneity and longevity of the mound settlements; the three mounds with contemporaneous occupation periods of 1000 years are all located within 4 \(km\) of each another (Jaimes Betancourt 2012, 2015). While our results suggest it might be possible for settlements in such close proximity to coexist as rivals if population densities are low (\(\leq 50\) people settlement\(^{-1}\)), the size and spatial complexity of these earthworks make this scenario highly unlikely (Lombardo & Prümers 2010; Prümers et al. 2022). It would be unlikely for such rival settlements to avoid taking defensive countermeasures (e.g., buffer zones; Denevan (1996, 2001), much less actively share substantial portions of cultivable land with them. For these reasons, we support the hypothesise by Prümers et al. (2022), based on extensive LiDAR mapping, that the Casarabe Culture developed a form of low-density urbanism, in which case neighbouring mound settlements were not rivals but instead belonged to the same socio-political network based on co-operation and co-ordination. However, while our results support coordination among neighbouring mound settlements, the impacts of such top-down organisation remain unclear, given that we simplified human decision-making to the household level. We intend to explore this possibility in future work.

An elaborate hypothesis: Model limitations

The outputs of MoundSim LandUse emphasise the numerous benefits of combining exploratory agent-based simulation techniques with empirical data collection (Premo 2007, 2010). For example, while our hypothesis that the Casarabe Culture engaged only in localised forest clearance has already been supported by pollen data (Whitney et al. 2013), our model provides additional conceptual clarity by forcing the user to specify the characteristics and behavioural dynamics used to produce this pattern of land-use (Lake 2015). In doing so, we gained insight into the potential mechanisms and motivations driving these patterns (Davis 2016; Premo 2010). For example, as our results demonstrate, one potential explanation for the absence of regional-scale vegetation clearance is the preference for intensive cultivation of desirable land, consistent with savanna phytolith data (Lombardo et al. 2025). Another benefit of our ABM is the ability to examine how these patterns may vary at fine spatial scales. As each agent acts autonomously with its behaviour informed by local environmental conditions (Macal & North 2010), local factors (e.g., the scarcity of savannas) can cause the agents in specific areas to deviate from the wider regional trend. For this reason, the spatially explicit maps of modified land displayed in Figure 8 can play a key role in guiding future archaeological and palaeoecological work, identifying these areas as candidates for further study.

We stress that the primary goal of our highly simplified model is to explore how the Casarabe Culture could have modified the landscapes of the southeastern LM, not to accurately reconstruct how they were modified. This approach was made necessary by the paucity of available palaeodata; just two mounds have been excavated in any detail (Jaimes Betancourt 2012; Prümers 2007, 2015) and published palaeoecological evidence in our immediate study area is restricted to only two sites – a large lake (Whitney et al. 2013) and an artificial pond (Lombardo et al. 2025). Modern ethnographic data can help to fill the gaps, but projecting this behaviour backwards to pre-Columbian times is problematic for several reasons (Roosevelt 1989). Additionally, even if sufficient archaeological data were available, as with the Kayenta Anasazi (Axtell et al. 2002; Janssen 2009), reproducing empirical trends is not necessarily sufficient to accurately reconstruct the past (Lake 2015; O’Sullivan & Perry 2013). The outputs of MoundSim LandUse should therefore be treated as the first step in an iterative process that can be further constrained as additional empirical data are obtained.

The limited empirical data surrounding the Casarabe Culture’s agricultural practices led us to implement household behaviour as a set of boundedly rational rules (Gigerenzer & Selten 2001; Simon 1955). This approach enabled us to directly tie environmental characteristics into the decisions made by household agents; the agent preference pathways provided environmental and logistical reasons to cultivate in certain areas (e.g., clearance difficulty; Denevan 1992a, 2001) without imposing restrictions upon them. However, we must recognise the challenges associated with incorporating human behaviour into agent-based systems (Crooks et al. 2018; Schlüter et al. 2017). Environmental factors account for only a proportion of those considered when making such decisions. Aside from the potential influence of top-down organisation (Lombardo & Prümers 2010; Prümers et al. 2022), cultural factors could have significantly affected how the Casarabe Culture utilised the landscape. This is demonstrated by the mounds themselves; reaching up to 20 m in height, these structures vastly exceed the height needed to prevent regular inundation (Nordenskiöld & Denevan 2009) and therefore imply a cultural purpose. We must also acknowledge that, given the Casarabe Culture inhabited this landscape for a millennium (Jaimes Betancourt 2012, 2015), these factors may have changed over time. For example, attitudes towards savanna cultivation may have changed alongside the construction of the causeway-canal network (Lombardo & Prümers 2010).

Additionally, it is important to consider how the ecosystems of the southeastern LM have evolved over time. To parameterise our model, it was necessary to rely upon the modern forest inventory datasets identified as anthropogenic (Erickson & Balée 2006; Townsend 1995), given the lack of appropriate alternatives (we compensate for this in our model by reducing resource supplies). However, these inventories might record a legacy of past human intervention, both from the Casarabe Culture as well as from the colonial era. Moreover, by utilising modern land-cover data, we also implicitly assume that the current spatial pattern of the forest-savanna mosaic has not significantly shifted over the past two millennia. This assumption is supported by palaeoecological data (Lombardo et al. 2025; Whitney et al. 2013), but southwestern Amazonia is also known to have experienced a climate-driven forest expansion beyond the LM during the late Holocene (Carson et al. 2014; Mayle et al. 2000). As such, climate-driven changes to the abundance and composition of the Casarabe Culture’s forests over the last two millennia, mediated by changes in flood and fire regime, cannot entirely be ruled out, which may have implications for the availability and productivity of forest resources.

Conclusion

Our highly simplified agent-based model, MoundSim LandUse, represents an initial attempt to leverage information currently available about the Casarabe Culture in order to explore how it may have modified the forests and savannas of the southeastern LM. The outputs from this model allow us to hypothesise that, contrary to previous claims (Erickson 2006; Erickson & Balée 2006), this culture only had a localised impact on forest and savanna vegetation (Whitney et al. 2013). Household agents were capable of altering the vegetation cover more widely, but their preference for cultivating land possessing desirable environmental characteristics (e.g., low elevation) drove them to repeatedly cultivate patches that they had already previously modified. For this reason, we hypothesise that the land utilised by the Casarabe Culture is likely to display signs of intensive modification, such as being enriched in economically useful species like the forests around the Ibibate mound complex (Erickson & Balée 2006). Our results further suggest that, since maize was cultivated in the open savannas (Lombardo et al. 2025), the Casarabe Culture may not have needed to clear forests to grow cereal crops. However, due to the close proximity of settlements, it may have been necessary for them to cooperate when making agricultural decisions to avoid conflict, consistent with an urban society (Prümers et al. 2022). While the outputs produced by exploratory models like MoundSim LandUse cannot, and are not intended to, reproduce the past (Premo 2010), these hypotheses can both inform, and be informed by, future empirical studies.

During sensitivity experiments, regional population size was identified as one of the most influential parameters in determining the total amount of land modified by household agents. However, while the population estimates used in our sensitivity experiments were high compared to the 2.0 people \(km^{-2}\) proposed by Denevan (1992b), the true population size of the Casarabe Culture remains unknown, and there are no estimates available in the literature. Many estimates for the broader region, such as the 0.15 people \(km^{-2}\) proposed by Steward (1949), appear unreasonably low considering the large, interconnected earthworks (Lombardo & Prümers 2010; Prümers et al. 2022). A second article, further developing MoundSim LandUse, has been published to help better constrain this demographic uncertainty (Hirst et al. 2025a).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the SCENARIO NERC doctoral training partnership (DTP) PhD scholarship to JH (NE/S007261/1). We thank Nicholas Payette, University of Oxford, for his help in reviewing the code for our agent-based model, as well as the CoHESyS modelling group, University of Oxford, for their valuable advice throughout the development and testing process. We also thank Iza Romanowska, Scott Heckbert, and Mark Lake for their advice following the initial development of our agent-based model, and Lisa Ringhofer for the additional information she provided with regards to the Tsimane indigenous group.

This work contributes to ICTA-UAB “Maria de Maetzu” Programme (CEX2024-001506/funded by MICIU/AEI / 10.13039/501100011033) and the Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca de Catalunya (SGR-Cat-2021, 00527)

Model Documentation

MoundSim LandUse has been developed in NetLogo 6.3.0 (Wilensky 1999), and a full ODD (Overview, Design + Details) description is available within the Supplementary Information (Grimm et al. 2006, 2010; Müller et al. 2013). The model code is available at this link: https://github.com/JoeHirst-Reading/MoundSim_LandUse.

Supplementary Information

The Supplementray Information files, including the full ODD, are available here: https://www.jasss.org/28/4/5/SI.pdf and here: https://www.jasss.org/28/4/5/SI2.pdf

References

APAZA, L., Wilkie, D., Byron, E., Huanca, T., Leonard, W., Pérez, E., Reyes-García, V., Vadez, V., & Godoy, R. (2002). Meat prices influence the consumption of wildlife by the Tsimane’ Amerindians of Bolivia. Oryx, 36(4), 382–388. [doi:10.1017/s003060530200073x]

AXTELL, R. L., Epstein, J. M., Dean, J. S., Gumerman, G. J., Swedlund, A. C., Harburger, J., Chakravarty, S., Hammond, R., Parker, J., & Parker, M. (2002). Population growth and collapse in a multiagent model of the kayenta anasazi in long house valley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(3), 7275–7279. [doi:10.1073/pnas.092080799]

BALEE, W. (1989). The culture of amazonian forests. Advances in Economic Botany, 7(1), 1–21.

BALEE, W. (2006). The research program of historical ecology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, 75–98.

BALEE, W. (2013). Cultural Forests of the Amazon: A Historical Ecology of People and Their Landscapes. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

BECKERMAN, S. (1987). Swidden in Amazonia and the Amazon Rim. In B. L. Turner II & S. Brush (Eds.), Comparative Farming Systems (pp. 55–94). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

BINFORD, L. (2001). Constructing Frames of Reference: An Analytical Method for Archaeological Theory Building Using Ethnographic and Environmental Data Sets. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [doi:10.1525/9780520925069]

BRUNO, M. (2010). Carbonized plant remains from Loma Salvatierra, Department of Beni, bolivia. Zeitschrift Für Archäologie Außereuropäischer Kulturen, 3, 153–208.

BRUNO, M. (2015). Macrorestos botánicos de la loma mendoza. In H. Prümers (Ed.), Loma Mendoza: Las excavaciones de los años 1999-2002 (pp. 285–296). Maputo: Plural Editores.

BUSH, M., McMichael, C., Piperno, D., Silman, M., Barlow, J., Peres, C., Power, M., & Palace, M. (2015). Anthropogenic influence on Amazonian forests in pre-history: An ecological perspective. Journal of Biogeography, 42(12), 2277–2288. [doi:10.1111/jbi.12638]

CARSON, J. F., Whitney, B. S., Mayle, F. E., Iriarte, J., Prümers, H., Soto, J. D., & Watling, J. (2014). Environmental impact of geometric earthwork construction in pre-Columbian Amazonia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(29), 10497–10502. [doi:10.1073/pnas.1321770111]

CEGIELSKI, W. H., & Rogers, J. D. (2016). Rethinking the role of agent-Based modeling in archaeology. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 41, 283–298. [doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.009]

CLEMENT, C. (1999). 1492 and the loss of amazonian crop genetic resources. I. The relation between domestication and human population decline. Economic Botany, 53(2), 188–202. [doi:10.1007/bf02866498]

CROOKS, A., Malleson, N., Manley, E., & Heppenstall, A. (2018). Agent-Based Modelling & Geographical Information Systems: A Practical Primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [doi:10.4135/9781529793543]

DAVIS, B. (2016). Logic and landscapes: Simulating surface archaeological record formation in Western New South Wales, Australia. University of Auckland, PhD Thesis.

DEAN, J. S., Gumerman, G. J., Epstein, J. M., Axtell, R. L., Swedlund, A. C., Parker, M. T., & McCarroll, S. (2000). Understanding Anasazi culture change through agent-based modeling. In T. A. Kohler & G. J. Gumerman (Eds.), Dynamics in Human and Primate Societies: Agent-Based Modeling of Social and Spatial Processes (pp. 179–205). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [doi:10.1093/oso/9780195131673.003.0013]

DENEVAN, W. (1963). Cattle ranching in the Mojos Savannas of Northeastern Bolivia. In Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers (Vol. 25, pp. 37–44). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [doi:10.1353/pcg.1963.0001]

DENEVAN, W. (1992a). Stone vs metal axes: The ambiguity of shifting cultivation in prehistoric Amazonia. Journal of the Steward Anthropological Society, 20(1–2), 153–165.

DENEVAN, W. (1992b). The Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

DENEVAN, W. (1996). A bluff model of riverine settlement in prehistoric Amazonia. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 86(4), 654–681. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1996.tb01771.x]

DENEVAN, W. (2001). Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [doi:10.1093/oso/9780198234074.001.0001]

DENEVAN, W. (2003). The native population of Amazonia in 1492 reconsidered. Revista de Indias, 63(227), 175–188. [doi:10.3989/revindias.2003.i227.557]

DICKAU, R., Bruno, M., Iriarte, J., Prümers, H., Jaimes Betancourt, C., Holst, I., & Mayle, F. (2012). Diversity of cultivars and other plant resources used at habitation sites in the Llanos de Mojos, Beni, Bolivia: Evidence from macrobotanical remains, starch grains, and phytoliths. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(2), 357–370. [doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.09.021]

DUFOUR, D. (1994). Diet and nutritional status of Amazonian peoples. In A. Roosevelt (Ed.), Amazonian Indians from Prehistory to the Present: Anthropological Perspectives (pp. 151–176). Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. [doi:10.2307/j.ctv2jhjwqs.11]

ERICKSON, C. (2006). The domesticated landscapes of the Bolivian Amazon. In W. Balee & C. Erickson (Eds.), Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical Lowlands (pp. 234–278). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [doi:10.7312/bale13562-011]

ERICKSON, C. (2008). Amazonia: The historical ecology of a domesticated landscape. In H. Silverman & W. Isbell (Eds.), The Handbook of South American Archaeology (pp. 157–183). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. [doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74907-5_11]

ERICKSON, C., & Balée, W. (2006). The historical ecology of a complex landscape in Bolivia. In W. Balee & C. Erickson (Eds.), Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical Lowlands (pp. 187–233). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [doi:10.7312/bale13562-010]

FEARNSIDE, P. (1980). Land use allocation of the transamazon highway colonists of Brazil and its relation to human carrying capacity. Land, People and Planning in Contemporary Amazonia. University of Cambridge Centre of Latin American Studies.

FEARNSIDE, P. (2006). Fragile soils and deforestation impacts: The rationale for environmental services of standing forest as a development paradigm in amazonia. In D. Posey & M. Balick (Eds.), Human Impacts on Amazonia: The Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Conservation and Development (pp. 158–171). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [doi:10.7312/pose10588-012]

FINEGAN, B. (1984). Forest succession. Nature, 312(5990), 109–114. [doi:10.1038/312109a0]

FLETCHER, R. (2009). Low-density, agrarian-Based urbanism: A comparative view. Insights, 2(4), 1–19.

GAO, J., Liu, Z., Zhao, B., Dong, S., Liu, P., & Zhang, J. (2020). Shade stress decreased maize grain yield, dry matter, and nitrogen accumulation. Agronomy Journal, 112(4), 2768–2776. [doi:10.1002/agj2.20140]

GIGERENZER, G., & Selten, R. (2001). Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

GOBIERNO Autonomo del Beni. (2019). Plan de uso del suelo del departamento del beni.

GOOD, K. (1987). Limiting factors in Amazonian ecology. In M. Harris & E. Ross (Eds.), Food and Evolution: Towards a Theory of Human Food Habits (pp. 207–421). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

GRIMM, V., Berger, U., Bastiansen, F., Eliassen, S., Ginot, V., Giske, J., Goss-Custard, J., Grand, T., Heinz, S. K., Huse, G., Huth, A., Jepsen, J. U., JNørgensen, C., Mooij, W. M., Müller, B., Pe’er, G., Piou, C., Railsback, S. F., Robbins, A. M., … DeAngelis, D. L. (2006). A standard protocol for describing individual-based and agent-based models. Ecological Modelling, 198(1), 115–126. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.04.023]

GRIMM, V., Berger, U., DeAngelis, D. L., Polhill, J. G., Giske, J., & Railsback, S. F. (2010). The ODD protocol: A review and first update. Ecological Modelling, 221(23), 2760–2768. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.08.019]

HANAGARTH, W. (1993). Acerca de la geoecología de las sabanas del beni en el noreste de Bolivia. Instituto de Ecología,

HERMENEGILDO, T., Prümers, H., Jaimes Betancourt, C., Roberts, P., & O’Connell, T. (2024). Stable isotope evidence for pre-colonial maize agriculture and animal management in the Bolivian Amazon. Nature Human Behaviour, 9, 464–471. [doi:10.1038/s41562-024-02070-9]

HIRST, J., Raczka, M., Lombardo, U., Chavez, E., Becerra-Valdivia, L., Bentley, M., Bronk Ramsey, C., Charidemou, M., Machlachlan, S., & Mayle, F. (2025a). Localised land-use and maize agriculture by the pre-Columbian Casarabe Culture in Lowland Bolivia. The Holocene, 35(8), 09596836251332794. [doi:10.1177/09596836251332794]

HIRST, J., Singarayer, J., Lombardo, U., & Mayle, F. (2025b). Constraining the population size estimates of the pre-Columbian Casarabe Culture of Amazonian Bolivia. PLoS One, 20(5), e0325104. [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0325104]

HODDER, I., & Orton, C. (1976). Spatial Analysis in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

HOLMBERG, A. (1969). Nomads of the long bow: The Siriono of Eastern Bolivia. Smithsonian Institution Institute of Social Anthropology Publication No. 10

HUANCA, T. (1999). Tsimane indigenous knowledge, Swidden fallow management and conservation. University of Florida, PhD Thesis.

JAIMES Betancourt, C. (2012). La Cerámica de la Loma Salvatierra, Beni-Bolivia. Maputo: Plural Editores.

JAIMES Betancourt, C. (2015). La cerámica de la Loma Mendoza. In H. Prümers (Ed.), Loma Mendoza: Las Excavaciones de los Años 1999-2002 (pp. 89–222). Maputo: Plural Editores.

JANSSEN, M. A. (2009). Understanding artificial Anasazi. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 12(4), 13.

LAKE, M. (2015). Explaining the past with ABM: On modelling philosophy. In G. Wurzer, K. Kowarik, & H. Reschreiter (Eds.), Agent-Based Modeling and Simulation in Archaeology (pp. 3–28). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

LANGSTROTH, R. (2011). Biogeography of the Llanos de Moxos: Natural and anthropogenic determinants. Geographica Helvetica, 66(3), 183–192.

LEVIS, C., Flores, B., Moreira, P., Luize, B., Alves, R., Franco-Moraes, J., Lins, J., Konings, E., Peña-Claros, M., Bongers, F., Costa, F., & Clement, C. (2018). How people domesticated Amazonian forests. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5, 171. [doi:10.3389/fevo.2017.00171]

LOMBARDO, U. (2023). Pre-Columbian legacy and modern land use in the Bolivian Amazon. Past Global Changes Magazine, 31(1), 16–17.

LOMBARDO, U., Canal-Beeby, E., & Veit, H. (2011). Eco-archaeological regions in the Bolivian Amazon: An overview of pre-Columbian earthworks linking them to their environmental settings. Geographica Helvetica, 66(3), 173–182. [doi:10.5194/gh-66-173-2011]

LOMBARDO, U., Hilbert, L., Bentley, M., Bronk Ramsey, C., Dudgeon, K., Gaitan-Roca, A., Iriarte, J., Mejia-Ramon, A., Quezada, S., Raczka, M., Watling, J., Neves, E., & Mayle, F. (2025). Maize monoculture supported pre-Columbian urbanism in southwestern Amazonia. Nature, 119–123. [doi:10.1038/s41586-024-08473-y]

LOMBARDO, U., May, J. H., & Veit, H. (2012). Mid- to late-Holocene fluvial activity behind pre-Columbian social complexity in the southwestern Amazon basin. The Holocene, 22(9), 1035–1045. [doi:10.1177/0959683612437872]

LOMBARDO, U., & Prümers, H. (2010). Pre-Columbian human occupation patterns in the eastern plains of the Llanos de Moxos, Bolivian Amazonia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(8), 1875–1885. [doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.02.011]

LOMBARDO, U., Szabo, K., Capriles, J. M., May, J. H., Amelung, W., Hutterer, R., Lehndorff, E., Plotzki, A., & Veit, H. (2013). Early and middle Holocene hunter-gatherer occupations in western Amazonia: The hidden shell middens. PLoS One, 8(8), e72746. [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072746]

MACAL, C., & North, M. (2010). Tutorial on agent-based modelling and simulation. Journal of Simulation, 4(3), 151–162. [doi:10.1057/jos.2010.3]

MAGLIOCCA, N., & Ellis, E. (2016). Evolving human landscapes: A virtual laboratory approach. Journal of Land Use Science, 11(6), 642–671. [doi:10.1080/1747423x.2016.1241314]

MANN, C. (2000). Earthmovers of the Amazon. Science, 287(5454), 786-789. [10.1126/science.287.5454.786]

MAYLE, F., Burbridge, R., & Killeen, T. (2000). Millennial-scale dynamics of southern Amazonian rain forests. Science, 290(5500), 2291–2294. [doi:10.1126/science.290.5500.2291]

MONTOYA, E., Lombardo, U., Levis, C., Aymard, G., & Mayle, F. (2020). Human contribution to amazonian plant diversity: Legacy of pre-Columbian land use in modern plant communities. In V. Rull & A. C. Carnaval (Eds.), Neotropical Diversification: Patterns and Processes (pp. 495–520). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. [doi:10.1007/978-3-030-31167-4_19]

MÜLLER, B., Bohn, F., Dreßler, G., Groeneveld, J., Klassert, C., Martin, R., Schlüter, M., Schulze, J., Weise, H., & Schwarz, N. (2013). Describing human decisions in agent-based models: ODD + D, an extension of the ODD protocol. Environmental Modelling and Software, 48(1), 37–48.

NORDENSKIÖLD, E., & Denevan, W. (2009). Indian adaptations in flooded regions of South America. Journal of Latin American Geography, 8(2), 214–224.

OLSON, D. M., Dinerstein, E., Wikramanayake, E. D., Burgess, N. D., Powell, G. V. N., Underwood, E. C., D’Amico, J. A., Itoua, I., Strand, H. E., Morrison, J. C., Loucks, C. J., Allnutt, T. F., Ricketts, T. H., Kura, Y., Lamoreux, J. F., Wettengel, W. W., Hedao, P., & Kassem, K. R. (2001). Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on earth. BioScience, 51(11), 933–938. [doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:teotwa]2.0.co;2]

O’SULLIVAN, D., & Perry, G. (2013). Spatial Simulation: Exploring Pattern and Process. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

PEÑA-CLAROS, M. (2003). Changes in forest structure and species composition during secondary forest succession in the Bolivian Amazon. Biotropica, 35(4), 450–461.

PILAND, R. (1991). Traditional Chimane agriculture and its relation to soils of the Beni biosphere reserve. University of Florida, PhD Thesis.

POORTER, L., Craven, D., Jakovac, C., van der Sande, M., Amissah, L., Bongers, F., Chazdon, R., Farrior, C., Kambach, S., Meave, J., Muñoz, R., Norden, N., Rüger, N., van Breugel, M., Zambrano, A., Amani, B., Andrade, J. L., Brancalion, P., Broadbent, E., & Hérault, B. (2021). Multidimensional tropical forest recovery. Science, 374(6573), 1370–1376. [doi:10.32942/x2r887]

POSEY, D. (1998). Diachronic ecotones and anthropogenic landscapes in Amazonia: Contesting the consciousness of conservation. In W. Balée (Ed.), Advances in Historical Ecology (pp. 104–118). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

PREMO, L. (2007). Exploratory agent-based models: Towards an experimental ethnoarchaeology. Digital Discovery: Exploring New Frontiers in Human Heritage. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology. Proceedings of the 34th Conference.

PREMO, L. (2010). Equifinality and explanation: The role of agent-based modeling in postpositivist archaeology. In A. Costopoulos & M. Lake (Eds.), Simulating Change: Archaeology Into the Twenty-First Century (pp. 28–37). Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

PRÜMERS, H. (2007). Charlatanocracia en Mojos? Investigaciones arqueológicas en la Loma Salvatierra, Beni, Bolivia. Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, 11, 103–116.

PRÜMERS, H. (2015). Loma Mendoza. Las Excavaciones de los Años 1999–2002. Maputo: Plural Editores.

PRÜMERS, H., Jaimes Betancourt, C., Iriarte, J., Robinson, M., & Schaich, M. (2022). Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon. Nature, 606(7913), 325–328.

RAILSBACK, S., & Grimm, V. (2019). Agent-Based and Individual-Based Modeling: A Practical Introduction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [doi:10.2307/jj.28274141]

RINGHOFER, L. (2010). Fishing, Foraging and Farming in the Bolivian Amazon. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. [doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3487-8]

RIRIS, P. (2018). Assessing the impact and legacy of swidden farming in neotropical interfluvial environments through exploratory modelling of post-contact Piaroa land use (Upper Orinoco, Venezuela). The Holocene, 28(6), 945–954. [doi:10.1177/0959683617752857]

ROMANOWSKA, I., Wren, C., & Crabtree, S. (2021). Agent-Based Modelling for Archaeology: Simulating the Complexity of Societies. Santa Fe, NM: Santa Fe Institute Press.

ROOSEVELT, A. (1989). Resource management in Amazonia before the conquest: Beyond ethnographic projection. Advances in Economic Botany, 7, 30–62.