From Local Actors to Leaf Carers: Companion Modeling for Rethinking Tree Protection in Senegal’s Groundnut Basin

, , ,

and

aUMI UMMSCO, Université Cheick Anta Diop, Dakar, Sénégal; bCIRAD, UMR SENS, Montpellier, France; cSENS, CIRAD, IRD, Université de Paul Valéry Montpellier, Montpellier, France; dCIRAD, Forêts et Sociétés, Montpellier, France; eIRD, Eco&Sols, Dakar, Sénégal

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (4) 6

<https://www.jasss.org/28/4/6.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5740

Received: 02-Sep-2024 Accepted: 12-Aug-2025 Published: 31-Oct-2025

Abstract

How can a participatory simulation model contribute to understanding social-ecological dynamics and fostering alternative strategies for the sustainable management of trees, considering their role in enhancing soil fertility and contributing to farmers' food security? In senegal's groundnut-growing region (Peanut Basin) , the Sahelian ecosystems have undergone significant degradation, characterized by a reduction in tree cover, as a consequence of the droughts in the 1960s and the 1990s. The Peanut Basin stands out for its positive interrelationships between trees, crops, and pastoralism. However, the regeneration of the Faidherbia albida tree population, essential to these interrelationships, has declined since the major droughts. Through collaborative efforts with agro-pastoral farmers living in the area, we developed a simulation model –- The SAFIRe model : Simulation of Agents for Fertility, Integrated Energy, Food security, and Reforestation –- that aims to identify, in collaboration with local communities, ways to reduce the pressure on tree populations and to restore conditions for medium-term tree regeneration. By exploring the results of the model co-designed with local stakeholders, we identified potentially more effective management strategies. More importantly, we have collectively questioned the conditions for improving tree cover and the viability of the socio-ecosystem, particularly in relation to the demand for firewood and local cereal for sustenance. This has prompted the stakeholders to engage in community-wide discussions and transform agro-pastoralists into leaf carers.Introduction

The Sahelian region has witnessed a series of devastating droughts from the 1960s to the 1990s, leading to substantial ecosystem degradation, particularly through a significant reduction in tree cover (Mbow et al. 2015). This loss adversely affected essential ecosystem services, impacting both the population and biodiversity. The severity of this tree cover loss becomes even more alarming given the rapid population growth in the Sahelian region (Cesaro et al. 2023). In a context of scarcity, intensive natural resource utilization by agriculture and livestock further exacerbates land degradation and soil fertility (Tappan et al. 2016).

Boserup & Chambers (1965) argued that declining soil fertility compels farmers to intensify agricultural practices to maintain productivity. While many studies have focused on this intensification as a central response to land pressure, less attention has been given to alternative strategies that seek to restore ecological functions – such as soil fertility – through the management of trees. This paper asks: how can participatory agent-based modeling help identify, with local communities, tree management strategies that relieve pressure on tree populations, support their regeneration, and contribute to food security by improving soil fertility?

Within DSCATT research project (Dynamics of Carbon Sequestration in Soils of Tropical and Temperate Agricultural Systems), operating in senegal’s groundnut-growing region (localy called Peanut Basin), participants in local living-labs quickly associated soil fertility with the presence of Faidherbia albida trees. This insight directed our research towards understanding the significance of trees in the agricultural practices of the Senegalese Peanut Basin. By examining tree usage and local management practices, we developed the SAFIRe model (Simulation of Agents for Fertility, Integrated Energy, Food Security, and Reforestation). This approach is part of Companion Modeling (ComMod) (Barreteau et al. 2003; Etienne 2014) and Companion Exploration (ComExp) (Delay et al. 2020), aiming to collaboratively explore potential futures for the territory.

In the context of sustainable land management, restoration options identified by farmers are closely linked to tree monitoring to mitigate predation risks from neighboring populations, especially in the longstanding conflict between farmers and herders. Two exploration pathways emerged from discussions with local communities: the impact of delegated surveillance to Senegalese Water, Forestry, hunting and soil conservation authority and the conditions for tree population development under community-managed surveillance.

The Rio Summit in 1992 marked a significant turning point in how natural resource management was envisioned. It contributed to the democratization of community-based approaches, encouraging a shift from top-down, authoritarian models toward more integrated and participatory frameworks (Delay et al. 2022). This evolution highlighted the importance of actively involving local stakeholders in the governance and management of their own environments. Since then, community-based natural resource conservation initiatives have been extensively documented and promoted (He et al. 2020; Maraseni et al. 2019; Selfa & Endter-Wada 2008). However, integrating communities into these processes also brings complex challenges—particularly when it comes to the co-construction of shared representations and understandings of socio-ecological systems. While the influence of different tree management regimes (delegated to forestry services or led by communities) has been widely debated, especially in terms of the territorial configurations they produce, our work raised a critical and often overlooked point related to how local actors interpret and respond to these issues.

In such complex social-ecological contexts – like the shared management of natural resources in rural areas – agent-based modeling (ABM) offers more than just the ability to simulate interactions between actors and their environment (Saqalli et al. 2009). The Companion Modeling (ComMod) approach uses agent-based systems to represent the diverse and sometimes conflicting perspectives of stakeholders, while establishing a continuous feedback loop between modelers and local actors (Becu et al. 2008). This process not only facilitates the exploration of scenarios, but more importantly, fosters stakeholders’ appropriation of the model and its insights. In doing so, it encourages what can be described as social learning (de Kraker et al. 2011). This form of learning goes beyond the acquisition of new information—it involves shifts in perception, and sometimes in behavior, regarding how collective problems are understood and addressed. Well-facilitated participatory models can act as powerful catalysts for dialogue by creating a “safe space” for collective experimentation and the emergence of new rules or practices.

With ComMod and ComExp approaches, we aim to assist stakeholders in reimagining future scenarios (Spelke Jansujwicz et al. 2021) that support desired territorial transformation. Our goal here is to facilitate discussions and enhance stakeholders’ capabilities through companion modeling. By adopting "Different Modelling Purposes" (Edmonds et al. 2019), we position our intervention within two categories: illustration and social learning (Le Page & Perrotton 2017). We see illustration as a means to discern viable paths by extensively exploring the co-constructed model. These illustrations should remain within a framework of social learning. It means that they are constructed to reflect the shared vision of stakeholders about the world. We assume that stakeholders’ will then be better positioned to leverage the results to transform their system.

In this article, we present how the SAFIRe participatory modeling process, embedded in this ComMod and ComExp framework, helped uncover overlooked drivers of tree loss – notably linked to changes in farming practices – and enabled stakeholders to collaboratively envision alternative tree management strategies. Rather than proposing definitive solutions, we aim to demonstrate how participatory simulation can act as a catalyst for shared understanding and adaptive decision-making in socially complex and ecologically vulnerable contexts.

Materials and Methods

Engaging communities in participatory resource management frameworks introduces complex challenges, particularly regarding the co-construction of shared representations and understandings of these environments. Integrating heterogeneous actors within collectives to co-construct models and simulations has emerged as an innovative response to these challenges. The simulations presented in this paper were the final step of a long participatory process we implemented with a group of local stakeholders of the Diohine area. Fully aligned with the philosophy of companion modeling, our project has given rise to novel methods. While facilitating workshops aiming at exploring alternative agricultural land management, we developed a participatory backcasting method we named ACARDI (Perrotton et al. 2021). This method relies on close collaboration between researchers and local actors to collectively (i) design a shared vision of a desirable future, (ii) identify transformative strategies through the design and use of conceptual models.

To explore this aspiration, we combined an anthropological approach with the co-construction of a simulation model with Netlogo (Wilensky 1999).

An ACARDI overview

The ComMod (Companion Modelling) approach was used to co-identify, together with dwellers (We chose to use the term dweller to refer to someone who inhabits a place through experience, practice, and care – closely attuned to their environment Ingold (2005)) their land management strategies – strategies that reflect their long-term objectives and constraints regarding their expectations. Because our collective inquiry centered on aspirations, we found it meaningful to propose renaming the method ACARDI (Aspirations, Constraints, Actors, Resources, Dynamics, Interactions). The facilitation process unfolded in three key stages, during which a shared vision was co-designed among the participants – between researchers and farmers, and among farmers themselves – reflecting the diversity of values, perspectives, and expectations held by each.

Two types of actor groups were mobilized: strategic groups (52 participants), composed of individuals with similar profiles (e.g., representatives from households with or without livestock, retailer, etc..), and a multi-stakeholder group (12 participants) , composed of representatives drawn from each strategic group (Bierschenk & Olivier de Sardan 1994). At the end of this process, ten priority aspirations were identified by the participants (Perrotton et al. 2021), among which was the “long-term preservation of a collective fallow area”, which this paper specifically explores.

- In the first stage, each of the five strategic groups—comprising ten individuals—engaged in a two-week workshop to articulate their shared aspiration.

- In the second stage, each group selected one or two representatives to bring forward their perspectives and concerns into a multi-stakeholder group, during a one-week workshop.

- In the third stage, the multi-stakeholder group worked together in a one-week workshop to synthesize the different aspirations and identify the constraints to their implementation.

This way of opening up the field of possibilities with participants allowed us, in the next phase of the project, to collectively negotiate which aspirations could be addressed within the project’s timeframe, and which could not. Among the ten identified aspirations, we chose to focus here on the return of fauna and flora, as it was highlighted by participants as a priority. At the same time, during this negotiation process, the research team considered it feasible to respond to this particular request.

Modelling for empowerment - An anthropological approach to participatory model co-construction

Following the ACARDI workshops, we conducted a three-month immersion in Diohine. This immersion, enabled an in-depth information collection process through interviews and participant observation. This fieldwork was essential for gaining a nuanced understanding of the local population’s aspirations and concerns regarding territorial management, particularly in regards to trees in agricultural land. It is during the phase of our work that we could, building on the mutual trust and understanding gained during the ACARDI workshops, create the first LivingLab of the Niakhar observatory (Delaunay et al. 2018).

We could hence develop and rafine specific conceptual models, gradually evolving into the creation of the SAFIRe agent-based model.Once again, this modelling process was a collaborative and iterative approach, actively involving the stakeholders of the newly created Diohine Living Lab who played a key role in discussing, evaluating, and validating each aspect of the SAFIRe model, thereby ensuring it accurately reflected their realities and expectations.

Following a thorough validation of the model with local stakeholders, described as expert validation (Bommel 2009), we began exploring the model using the OpenMole platform (Reuillon et al. 2013). OpenMole1 is an open-source software platform designed for creating and executing massively parallel experiments on complex numerical models using distributed computing infrastructures. OpenMole embeds a number of exploration methods, from the most traditional (sampling, Latin square, etc.) to the most elaborate (based on genetic algorithms). Model exploration with OpenMole allows researchers to test various parameter configurations to better understand the model’s behavior, identify the most significant scenarios, and optimize the outcomes.

This phase of exploration enabled us to simulate a variety of scenarios and to collect substantial results, which were then brought back to the Living Lab participants for feedback and collective interpretation. To support this critical moment of dialog and engagement, we used an interactive interface – built using R and the plotly package (R Core Team 2023; Sievert 2020) – intended to ease the manipulation and interpretation of complex datasets by stakeholders, thereby fostering a smoother, more collaborative experience.

Indeed, a static scatter plot often acts as an opaque representation for participants, making it difficult to trace how specific parameter configurations led to particular outcomes. Responding to their questions in real time becomes time-consuming and, at times, detrimental to the participatory rhythm of the workshop. We therefore set up a minimal but functional interface that allows for the representation of multiple variables and, crucially, enables users to interact directly with the data. By simply hovering over a point, participants can access the underlying simulation parameters that led to a given result (see panels s1 and s2 in Figure 2).

ODD

In this section, we will describe the SAFIRe model (Simulation of Agents for Fertility, Integrated Energy, Food security, and Reforestation) using the ODD (Overview, Design concepts, and Details) framework (Grimm et al. 2006, 2010, 2020)

Overview

Purpose. The Peanut Basin is facing a loss of soil fertility. Chemical amendments are either unavailable in the area or economically inaccessible for farmers. Therefore, soil fertility depends on two aspects: the presence of livestock in the territory to maintain year-round manure, and the Faidherbia Albida trees which have the unique characteristic of shedding their leaves during the growing season and fixing nitrogen from the air into the soil. From their point of view, the decline in tree population is strongly linked to individual practices associated with pastoralism

The objective of this work was co-defined with the participants and echoes their concern for the decrease in the density of the Faidherbia population in the area, for which they mostly blamed individual practices linked with pastoralism. Starting from their desire to restore trees and biodiversity, we collectively engaged a modelling process to (i) reassess the functioning of the social-ecological system, (ii) examine the role of farmers and agropastoralists in the disappearance of trees with a focus on “tree cutters”, and (iii) evaluate and explore solutions for managing the Faidherbia population to increase their density through the comparison of community-based surveillance efforts versus centralized surveillance conducted by guards from the Senegalese Water, Forestry, hunting and soil conservation authority.

Throughout the study, we also examined the role of farmers and agro-pastoralists in the disappearance of trees.

Entities, state variables and scales. The entities in the model are relatively numerous: some are static (trees, plots, and village), while others are in motion (shepherds, farmers, woodcutters, and overseers).

patches: nbarbresici: Number of trees present on this patch; arbre-ici: Indicates if there is a tree on this patch (reference to a specific tree); tree-influence: Influence of the tree on this patch (can represent aspects like shade, nutrients affected by the tree, etc.); under-tree: (TRUE/FALSE) Indicates if the patch is under a tree; culture: Type of crop on this patch (can be millet or groundnut); en-culture: Indicates if the patch is currently used for crops; rendement-mil-g: Yield of millet on the patch in terms of grains (to be calibrated later); rendement-mil-p: Yield of millet on the patch in terms of bundles; rendement-groundnuts-g: Yield of groundnuts on the patch in terms of grains; rendement-groundnuts-p: Yield of groundnuts on the patch in terms of bundles; id-parcelle: Identifies the parcel, allowing the structure of the parcels to be maintained during rotation; pas-rotation: Tracks parcels that have not yet rotated (system of +1); rotation: (TRUE/FALSE) Indicates if the parcel has already undergone rotation; champ-brousse: Indicates if the patch is in bushland; zoné: (TRUE/FALSE) Indicates if the patch is used for defining fallow zones; zone: Indicates to which fallow rotation zone the patch belongs (there are 3 zones for fallow rotation).

Trees: proche-village: Likely unnecessary variable (trees in villages are also pruned); nb-coupes: Number of cuts; nb-jour-coupe: Number of cutting days; age-tree: Age of the tree. Trees have olso a subclass Saplings composed by age: Age in days; signalé: Reported; rna-coupe: Cut in RNA.

farmers: id-agri: Links to the farmer’s unique parcel; engagé: TRUE/FALSE engagement in the Assisted natural regeneration (RNA in fr); interet-RNA: Interest in the RNA; jour-champ: Days spent in the field; nb-ha-a: Number of hectares allocated; stock-mil: Stock of millet; idMyBerger: Identifier of the associated shepherd; nb-patches: Number of patches; mon-chp-RNA: Field in the RNA.

hearder: troupeau-nourri: does the herd have enough to eat, currently TRUE/FALSE; arbre-choisi: tree chosen to be cut and fed to animals as fodder; nb-têtes: herd size for the shepherd; nb-ha-b: Between 3.8 (newly settled, 11%) and 5.5 (89% of the population); stock-fourrage: Forage stock; idAgri: Identifier of my reference farmer.

woodcutters: attrape: Captured (TRUE/FALSE); nb-attrape: Number time he was captured; jours-peur: Days of fear after capuration; en-coupe: Currently cutting.

The simulated space, through which the agents interact, represents 100 hectares. It is composed of 1000 spatial entities (patches) each with a size of 10 square meters (resolution). It is exclusively agricultural since the inhabited area of the village is condensed into a single point (The areas that are not cultivated, such as wetlands and pathways, are rare and have not been represented).

The irreducible time step is one day (tick). The various elements of the system (interactions, etc.) take into account the seasonality that structures agricultural activities. Every 365 days, a new year begins and the rhythm of the seasons continues. A second time unit can be considered: the year, which consists of seasons. Simulations are generally carried out over 23 years. At the beginning of the simulation, the first 3 years are considered to initialize the model.

Process overview and scheduling. This section provides an overview of the processes and their scheduling within the model. The model is composed of several sub-models that simulate various aspects of the ecosystem and human activities. Each process is organized and executed in a specific sequence to reflect the interactions and dependencies within the system. The following describes repeated procedures that occur at each time step:

- Harvest and Crop Management

- Harvest and stockpiling: Farmers harvest crops and store them in their stockpiles.

- Effect of machinery on unprotected saplings: Machinery used in the fields may damage or destroy unprotected saplings.

- Crop rotation: Farmers rotate crops between different fields to maintain soil fertility and reduce pest buildup.

- Tree Growth and Reproduction

- Sprouting: New saplings sprout around mature trees, influenced by tree density and environmental conditions.

- Sapling growth: Saplings grow over time, with growth rates dependent on available resources and environmental factors.

- Aging and death of trees: Trees age and may eventually die due to old age, disease, or other environmental factors.

- Livestock Feeding and Forage Use of Acacias

- Feeding livestock with straw: Shepherds feed their livestock with straw collected from the fields.

- Tree cutting: Trees are cut down for forage or other uses by the shepherds.

- Livestock in fallow land and cutting of saplings: Livestock graze in fallow lands, and shepherds may cut down saplings to manage the land.

- Cutting of Saplings by Woodcutters

- Detection of saplings: Woodcutters search for and identify saplings that can be cut.

- Cutting of saplings: Once identified, saplings are cut by the woodcutters for use as firewood or other purposes.

- Farmer Engagement

- Participation in meetings: Farmers participate in community meetings to discuss agricultural practices and share knowledge.

- Observing the success of neighbors: Farmers observe the practices and successes of their neighbors to learn and adapt.

- Social interaction and motivation: Social interactions among farmers influence their motivation and engagement in community activities.

- Protection of saplings: Farmers take actions to protect saplings from damage by livestock or machinery.

- Surveillance

- Surveillance and presence of farmers in the fields (generalized community surveillance): Farmers patrol their fields and monitor for any issues such as pests or unauthorized grazing.

- Delegated community surveillance: Specific individuals or groups are assigned the task of surveillance to ensure all fields are watched effectively.

Design Concepts

Basic principles. In their paper, Roupsard et al. (2020) established a link between the presence of Faidherbia albida trees and the improvement of crop yields in the region. We have extended this work to calibrate the model on the relationship between these trees and cultivated plants. By engaging with stakeholders on their interactions with plants through food and livestock, we aimed to address the paradox of the non-renewal of these trees in a holistic way, considering biological and social dynamics involved. Given that the area has been well-documented by agronomists since the establishment of the Niakhar observatory, we were able to collect quantitative data on historical (Pelissier 1966; Pieri 1989) and contemporary (Audouin et al. 2018; Ba et al. 2018) forms of rural organization. This comprehensive documentation facilitated our understanding and analysis of the agricultural systems and social structures within the region. This work primarily involved adopting a systemic approach as identified by the stakeholders during participatory modelling workshops using the ARDI method (Etienne et al. 2011; Etienne 2014)

Adaptation. Two agents exhibit adaptive/changing behaviors: the woodcutters and the farmers. The response of the woodcutters to being caught by a sapling protector varies according to the number of times they have been caught previously. Farmers have a score describing their interest in tree protection. This score evolves constantly according to several rules: encountering another engaged farmer, observing the success of a neighbor’s protection system, participating in meetings, etc.

Emergence. There are several intriguing elements to examine, such as the emergence at the model level and the enhanced understanding of social and ecological interrelationships and solidarity among the actors. The model emphasizes the significant impact of agriculture (likely due to the introduction of plow-based farming) on the destruction of Faidherbia albida saplings (weak emergence). Moreover, a strong emergence is observed when agents are permitted to organize on a community level, as neighbors gradually engage each other in sustaining interest in assisted tree regeneration.

Highlighting potential long-term trajectories to reach acceptable production volumes should be considered both from the viewpoint of weak emergence within the model, due to its mechanistic processes, and strong emergence, as it drives participants to actively engage and commit to the theme beyond the facilitation process.

Sensing. The patches within the action radius of the trees will yield more. Agents are capable of perceiving the farmers around them. Shepherds will not cut young saplings if there is a concerned farmer nearby, and the same applies to woodcutters. Farmers, in turn, perceive their neighbors and will interact with them if they have adjacent fields. Through these interactions, they discuss assisted natural regeneration (ANR) to persuade each other to adopt this practice.

Interaction. The interaction between agents is direct. Woodcutters interact directly with the saplings by cutting them down. Similarly, shepherds interact directly with the trees by utilizing them for forage. Farmers and supervisors also have direct interactions with woodcutters by stopping them from cutting the saplings. Additionally, farmers destroy young saplings that are not cared for.

- Woodcutters and Saplings: Woodcutters seek out saplings and cut them down for use as firewood or other purposes. This direct interaction reduces the number of saplings in the environment.

- Shepherds and Trees: Shepherds interact with trees by feeding their livestock with tree foliage or cutting down trees for forage. This direct interaction affects the tree population and influences the availability of forage resources.

- Farmers and Woodcutters: Farmers interact with woodcutters by attempting to stop them from cutting saplings. When farmers encounter woodcutters in the field, they may intervene to take care of the saplings.

- Supervisors and Woodcutters: Supervisors, acting as carers, also interact directly with woodcutters. They monitor the fields and stop woodcutters from cutting down saplings to ensure the protection of young trees.

- Farmers and Unprotected Saplings: Farmers destroy young saplings that are not protected. This interaction occurs when farmers are working in their fields and come across unprotected saplings, which they remove to prevent interference with their crops.

Stochasticity. Many events in the model rely on stochasticity since they are probabilistic. Probability is often used as a frequency measure. This is the case for the movements of farmers in their fields and the probability that farmers will discuss the RNA (Assisted natural regeneration) with each other.

Stochasticity is used to represent uncertainty, particularly concerning whether supervisors catch woodcutters. Since supervisors do not spend the entire day in a single field, they may visit a field without encountering the woodcutter.

Finally, randomness is used to create variability in initial conditions. This is the case for the number of heads in different herds, which vary in size, and for the initial age of each tree, resulting in trees of varying ages.

- Partial Randomness as Uncertainty

- Farmer Movements: The movements of farmers within their fields are determined randomly. This means that their location at any given time is based on a probability distribution, ensuring variability in their positions.

- Discussions about RNA: The likelihood that farmers will engage in discussions about the RNA is also probabilistic. This frequency-based probability allows for random interactions among farmers, influencing their engagement with the RNA.

- Supervisors and Woodcutters: The uncertainty in supervisors catching woodcutters is modeled using partial randomness. Supervisors patrol fields but may not always encounter woodcutters due to the random nature of their patrol routes and the woodcutters’ activities.

- Randomness for Initial Variability

- Herd Sizes: The initial number of heads in each herd is determined randomly, resulting in herds of varying sizes. This introduces variability into the model, reflecting real-world differences in herd sizes.

- Tree Ages: The initial age of each tree is assigned randomly, creating a population of trees with a range of ages. This variability in tree ages ensures a more realistic representation of a forest with trees at different stages of growth.

Collective actions. Collective forms emerge with the engagement of farmers in the protection of saplings. The larger the group of engaged farmers, the more likely it is for others to join, and the more assured the group’s longevity.

- Farmer Engagement: As farmers begin to engage in sapling protection, they form groups that work collectively towards this goal.when they meet (spatial proximity) they discuss how to improve their ability to protect the trees. They also take part in awareness-raising meetings.

- Group Growth: The probability of additional farmers joining the group increases with the group’s size. This creates a positive feedback loop where the more farmers are engaged, the more likely it is for others to join.

- Group Longevity: The sustainability of the group is enhanced as it grows. A larger group of engaged farmers is more resilient and capable of maintaining their collective efforts over time.

Observation. The simulation involves the monitoring of several metrics:

- Millet and Groundnut Production: This indicator tracks the total production of millet and groundnut in the simulation. It helps assess the agricultural output and food security within the modeled environment.

- Number of Trees at Each Development Stage: This metric measures the number of trees at various stages of development, such as saplings, young trees, and mature trees. It provides insight into the growth dynamics and regeneration of the forest.

- Number of Trees Destroyed by Each Type of Agent: This indicator counts the number of trees destroyed by different agents, such as farmers, woodcutters, and livestock. It helps understand the impact of various human and animal activities on the forest.

- Volume of Wood Cut for Cooking: This metric tracks the amount of wood harvested specifically for cooking purposes. It helps assess the pressure on forest resources for domestic energy needs.

- Age of Each Tree Sapling: This indicator measures the age of each sapling in the simulation. It provides information on the regeneration rate and the survival of young trees.

- Number of Farmers Engaged in the RNA: This metric tracks the number of farmers actively participating in the National Agricultural Network (RNA). It helps evaluate the level of community involvement and engagement in agricultural and environmental initiatives.

Details

Initialization. At initialization, the environment is generated with the following steps:

- Generation of Parcels and Crops: The landscape is divided into parcels, each designated for specific types of crops. This step sets up the agricultural fields and assigns crop types to each parcel.

- Generation of Trees and Their Fertilizing Effects: Trees are distributed throughout the environment, considering their effects on soil fertility. Trees influence the nutrient levels of the patches they occupy, enhancing soil quality in their vicinity.

- Generation of Human Agents: Human agents, including shepherds, woodcutters, farmers, and supervisors, are created and placed in the environment. Each agent type has specific roles and behaviors that contribute to the model’s dynamics.

- Generation of the Village: The village is established as a central location where human agents reside. This step involves setting up the village infrastructure and assigning homes to the agents.

Input data. We don’t use input data.

Submodels. Harvest and Crop Management:

- Harvest and stockpiling: At the onset of the dry season, annual stocks of peanuts, millet, and millet straw are established. These global variables are measured in kilograms for peanuts and millet, and in bundles for millet straw. Each patch is assigned a yield based on its crop type and proximity to a tree.

- Fallow patches produce nothing. Others yield amounts equivalent to average yields found in the literature.

- For patches under trees (under-tree), a coefficient representing an increase in fertility is applied to the initial average yield.

- For each shepherd, an individual forage stock is defined by distributing the global millet straw stock to patches. The forage stock is a product of the straw stock at the patch multiplied by the number of hectares the shepherd owns, which is randomly defined at initialization.

- Effect of machinery on unprotected saplings: Machinery used in the fields may damage or destroy unprotected saplings that are less than 3 years old and located in cultivated fields.

- Crop rotation: Farmers rotate crops between different fields to maintain soil fertility and reduce pest buildup. Each year, all fields are first converted to millet cultivation. Then, until 20% of the patches are fallow, distant fields from the village (bush fields) are sequentially turned into fallow land. The same procedure is repeated for remaining millet fields until 20% become peanut patches. Fields that have been continuously millet for several years are prioritized. Millet fields that did not rotate this year receive a fertility penalty.

Tree Growth and Reproduction:

- Sprouting: Within a radius of 10 patches around trees older than 8 years, three new saplings appear. This number was proposed by the participants and reflects their estimation of how many young trees, among the hundreds of seeds produced annually by a mature tree, have the potential to reach adulthood. Trees that have been cut less than 4 years ago do not produce offshoots. This figure is based on the time it takes for a tree’s foliage to fully regenerate.

- Sapling growth: A day counter is used to assign an age to each sapling. Once this counter exceeds 3000 (equivalent to 8 years), the saplings become trees. The patches around new trees are now considered more fertile (under-tree). The tree counters for field agents are also increased with each new tree.

- Aging and death of trees: Tree growth initially involves the regeneration of foliage following a cut, taking 4 years to fully regenerate. After 4 years, cut trees can produce offshoots. The life expectancy of a tree in the simulation is 100 years, which may be reduced by 20 years if the tree has been cut more than four times. When a tree dies, the patches around lose their "under-tree" status and the associated fertility boost.

Livestock Feeding and Forage Use of Acacias:

- Feeding livestock with straw: Shepherds use their forage stocks to feed their livestock. The daily amount given is determined by the number of heads in the herd and the consumption per head, calibrated at 0.4 bundle/cow.

- Tree cutting: If the forage stock is exhausted, the shepherd feeds his livestock by cutting down trees. Once a week, if there are uncut trees remaining, he randomly chooses one and cuts it. The tree still fertilizes the surrounding fields but no longer produces offshoots. Following the cut, the herd is fed and the global wood fuel stock increases by one cart.

- Livestock in fallow land and cutting of saplings: During the crop season, shepherds and livestock remain on fallow patches. If there are no farmers engaged in protecting saplings within a 10-patch radius around the shepherd, nearby saplings (within a 3-patch radius), protected or not, are eaten and disappear.

Cutting of Saplings by Woodcutters:

- Detection of saplings: Woodcutters, who have not been caught recently (within the year), move to a random patch. If there are intermediate-sized saplings aged 3 to 8 years within a 10-patch radius, they move towards one of them. The sapling in question disappears if the cutter is not caught by a supervisor.

Farmer Engagement:

- Farmer Engagement: The engagement of farmers in protecting F.A saplings depends on an individual score called "interest in RNA." Farmers with a score of 100 or more start to protect their saplings. This score can increase or decrease based on various procedures. If their interest score falls below 0, the engaged farmers disengage. Changes in farmers’ interest scores start only after 1092 iterations, which corresponds to 3 simulated years.

- Participation in meetings: Farmers participate in community meetings to discuss agricultural practices and share knowledge. The frequency of meetings is chosen before the simulation starts. For each meeting, a number of unengaged farmers are randomly selected. The number of meeting participants is also determined before the simulation. Following these meetings, participants see their interest in protection increased by 50 points.

- Observing the success of neighbors: Unengaged farmers who observe the success of a neighbor can increase their interest score by 75 points. For this to happen, the farmer must see, within a 20-patch radius around their field, a field where more than 2 trees have regenerated.

- Social interaction and motivation: Social interactions among farmers influence their motivation and engagement in community activities. Discussions are the only procedure that allows already engaged farmers to increase their interest score. When in their field, farmers look for other engaged farmers around them. If there are none, the interest score decreases by 0.2 points. If there is an engaged farmer nearby, a discussion may potentially take place. A discussion index between 0 and 100 is determined before the simulation. A number is randomly drawn between 0 and 99. If it is higher than the discussion index, the discussion does not take place and the score decreases by 0.2. Conversely, the score increases by 1. Thus, the higher the discussion index, the more likely farmers are to engage in discussions.

- Cutting of protected saplings and disengagement: When a protected sapling is cut in a field, the associated farmer loses 5 points of interest.

- Protection of saplings: Once in their field, if engaged farmers see an unprotected sapling, they protect it. If there are multiple unprotected saplings, they do not protect all at once but one at a time, during successive iterations.

Surveillance:

- Surveillance and presence of farmers in the fields (generalized community surveillance): Farmers patrol their fields and monitor for issues such as pests or unauthorized grazing. The presence of farmers in their fields begins with the start of the rainy season (day of the year > 140). A field time index, ranging from 0 to 100, is determined before the simulation. At each iteration and for each farmer, a random number is drawn between 0 and 99. If this number is higher than the field time index, the farmer stays in the village; otherwise, he goes to his field. For farmers with a field distant from the village, a "bush field" as locally termed, the field time index is reduced by a bush presence coefficient. This coefficient is also defined before the simulation. Farmers engaged in protecting their saplings, who are present in their fields, monitor woodcutters. If the field has undergone numerous cuts, the farmer is extremely vigilant and surprises all woodcutters within a radius of 10 patches. For engaged farmers who have not yet experienced many cuts, the probability of stopping woodcutters is lower. A propensity to denounce index is set before the simulation, linked to the protectors’ lack of attention and their leniency towards the woodcutters.

- Delegated community surveillance: Specific individuals or groups are assigned the task of community surveillance to ensure all fields are effectively monitored. This "delegated" surveillance involves a predefined number of overseers who visit a fixed number of fields each day, also determined before the simulation. They target fields successively, visiting only those that have not yet been inspected. Once in the fields, they have varying chances of catching a woodcutter within a radius of 10 patches. The more fields they visit per day, the lower the probability of catching a woodcutter, as overseers spend less time in each field. Delegated surveillance can be conducted in coordination with protective farmers. If coordinated surveillance is chosen before the simulation, overseers first visit fields where saplings are protected; otherwise, the choice of fields to visit remains random.

Statistical analysis and our companion modelling approach

Our work brings together companion modelling (e.g., Barreteau et al. (2003)) and companion exploration (Delay et al. 2020), that is the collective design and use of models to promote collective thinking and learning, deepened by the collective exploration of the models hence produced. To achieve this, we employed traditional agent-based modeling tools and made a concerted effort to conduct these analyses with the farmers of the Peanut basin, engaging them in discussions about the exploration results. We performed a sensitivity analysis and utilized the "pattern space exploration" method to produce results reflecting the range of possible long-term scenarios. These results were then discussed with the stakeholders to ensure a comprehensive understanding and validation.

Sensitivity analysis: Saltelli method

Sensitivity analysis comprises a range of techniques that assess how a model responds to variations in its input parameters. These statistical methods aim to quantify the extent to which changes in the inputs influence the variability observed in the outputs. In accordance with the definition provided by (Saltelli et al. 2008), sensitivity analysis determines the "relative importance of each input in determining [output] variability". Consequently, these methods often yield a ranking or ordering of the inputs based on their respective sensitivity levels.

Pattern Space Exploration (PSE)

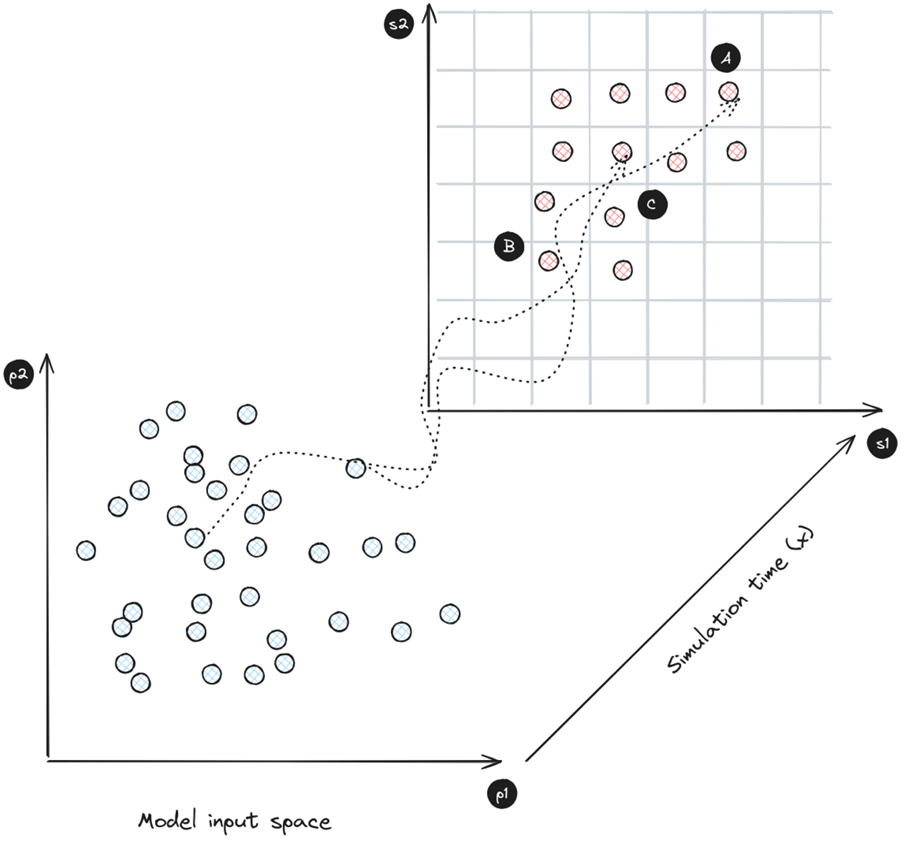

The PSE method (Chérel et al. 2015), based on genetic algorithms, is specifically designed to comprehensively cover the output space, resulting in its maximum score in output exploration – e.g. "explore the output’s diversity of a model"2. By exploring the output space, the PSE method uncovers new patterns, providing insights into the model’s sensitivity by examining the corresponding input values. In Figure 2 the input parameters (p1 and p2) are shown in blue and generate time-based trajectories (dotted arrows) of the simulation outputs (s1 and s2). The values of s1 and s2 (red in Figure 2) are discretized, and the PSE algorithm aims to reach every cell within the output grid. As a result, the presence of a point in a grid cell is just as informative as its absence. A, B, and C represent output results that are sufficiently contrasted, having reached different areas of the discretized output grid. Unlike calibration-based methods, PSE’s effectiveness is influenced by the dimensionality of the output space, as it keeps a record of all the covered locations during exploration.

In addition, the PSE method usually takes stochasticity into account by estimating selected models using the median of multiple output values obtained from model runs. For our purposes, and as we are in a situation where the results need to be discussed with stakeholders, we have chosen to focus not on the median, but on the last decile. This means that simulations are retained if more than 90% of the results converge towards the identified output.

The algorithm’s ability to explore a diversity of output forms is extraordinarily powerful in the context of companion modeling. Indeed, participants in co-construction sessions gradually became accustomed to the practice of modeling (Etienne 2014). They developed the ability to interrelate various elements of the system. However, the strength of agent-based modeling lies in the fact that they cannot anticipate emergent phenomena. Once the model has gained sufficient confidence, questioning the group about marginal aspects or unconsidered input parameter sets in the model proves to be extremely fruitful from the perspectives of emancipation and anticipating unforeseeable situations.

Engaging stakeholders in results and thresholds discussions

Working with participants on the PSE results enabled us to address the final conditions and thus the various configurations of the future. To facilitate this, we organized a feedback workshop during which we presented the simulation outcomes and discussed their implications for the systems they had described.

Subsequently, we engaged in a moment of collective reflection, during which participants collaboratively articulated the final conditions that resonated most strongly with their lived experience. Their situated interest in the simulation outputs (s1 and s2 in Figure 2) led us, during the workshop, to revisit the input parameters (p1 and p2 in Figure 2) and to re-run model trajectories. These simulations were not treated as abstract outputs, but as narrative provocations-tools for grounding discussion, challenging assumptions, and weaving the model more tightly into the fabric of their realities.

These archetypal outputs opened the way to engage with and make sense of situations that had previously remained unthinkable or invisible (Banos 2010). In Figure 2, situations A, B, and C can be read as a series of contrasting outcomes – material traces of different trajectories through the model’s space. Each of these can be translated into a narrative scenario by re-running simulations with their corresponding input parameters (p1 and p2). These scenarios become shared objects of inquiry – starting points for discussions with participants about the configurations, decisions, and contextual elements that may have produced such outcomes in their lived landscapes. This leads to extremely rich discussions that compel stakeholders to consider these previously unthinkable situations and to collectively discuss the processes for satisfying individual needs regarding the collective inputs.

Results

The Simulation Interface: What Matters to Participants

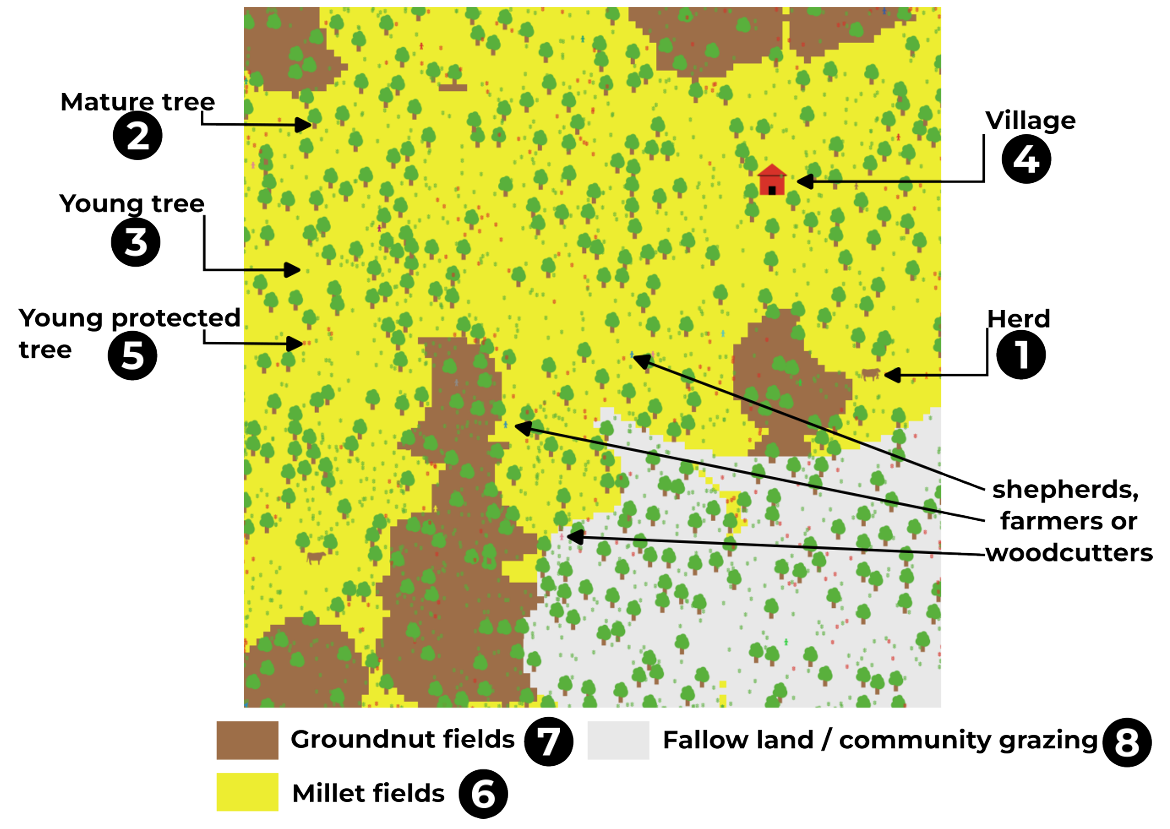

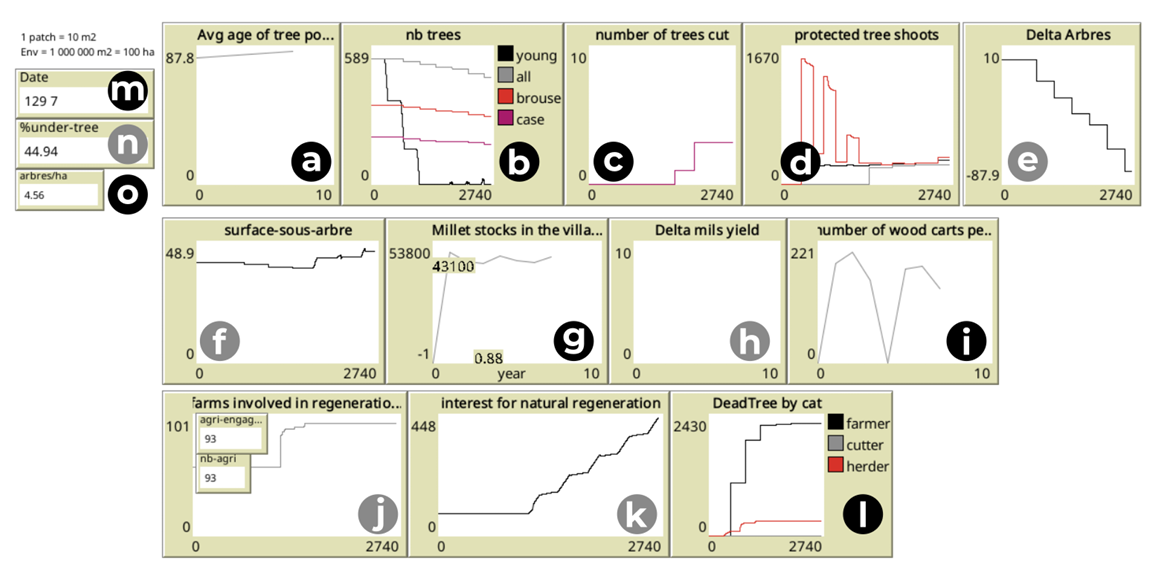

The graphical interface of the model is shown in Figures 3 and 4. This section focuses on our approach and methodology aimed at bringing this aspiration to life, combining socio-cultural aspects and modeling tools for a holistic understanding.

The entities identified by participants during the conceptual phase (reported in Section 2.15) are made visible within the spatially explicit environment of the simulation (Figure 3). These figures – trees, animals, plots, and other semiotic companions – inhabit the modeled space not merely as abstractions, but as anchors for collective attention and memory. Through their movement and interactions over time and space, participants are able to track agent behaviors and engage in what is known as "face validation" – a form of expert-based judgment that affirms (or questions) the fidelity of the translation from the shared conceptual model built during co-design sessions to the simulated dynamics unfolding on screen. When dissonance or gaps emerge between expected and observed behaviors, these are not ignored but become sites of discussion and revision, where the model becomes a living artifact – something to be adjusted, re-narrated, and re-aligned with the situated knowledges of those who shape it.

Once participants in the workshops succeeded in validating the spatial behaviors of the simulation model, they were then able to ascend to a more abstract level of engagement. They no longer question the behaviors and interactions of the agents with their environment – for example, “Why is the herd in the groundnuts fields at this time of year?” – but instead begin to interrogate the model as a whole – for instance, “What happens if we increase the number of herds in the village area?”. At that point, they expressed a desire to interrogate the model through aggregated indicators (see Figure 4). Most of the indicators presented here (in black) emerged from the concerns and questions raised by the workshop participants themselves. Others (in grey), however, were introduced by the researchers – not to override stakeholder perspectives, but to ensure the model’s internal consistency, or to trace dynamics that, while initially of little interest to participants, held significance for understanding the system’s underlying mechanisms.

If the model is able to provide answers that resonate meaningfully with all actors involved—both dwellers and researchers – then the systematic exploration phase can move to a higher level of abstraction, focusing solely on end-of-simulation outputs. The trajectories are then recontextualized collectively, as participants interpret the simulation results in light of their situated knowledge and experiences.

Understanding stakeholders variable importance via sensitivity analysis

We conducted the same analysis twice on different simulation scenarios. First, we performed an analysis on the community surveillance system. The second analysis shifts the workload to a dedicated surveillance system to mimic the functioning of surveillance by a Senegalese Water, Forestry, hunting and soil conservation authority guards.

Comparing these two analyses allows us to assess the influence of a change in practice on the system’s operation and to identify the structural changes they induce.

In a community surveillance scenario, the global sensitivity analysis shows that the probability of discussing the importance of trees plays an extremely significant role in both millet production (\(0.72\)) and the total number of trees (\(0.59\)) at the end of the simulation (see Table 1).

he frequency of awareness meetings about the benefits of trees has a role, albeit more limited, in the number of trees (\(0.23\)) and millet production (\(0.30\)). Similarly, the time spent in the fields also affects the number of trees (\(0.29\)) and millet production (\(0.16\)).

Finally, the probability of reporting a woodcutter when seen impacts the number of trees (\(0.25\)) but less so millet production (\(0.12\)).

The presence in the bush has little importance on both the number of trees and millet production.

In a scenario where a Senegalese Water, Forestry, hunting and soil conservation authority guards watch the trees, dynamics change a little (c.f. Table 2). This is because the surveillance is no longer carried out by the local population.

Time spent in the field and the probability of discussing a subject related to tree protection are two parameters that have a relatively strong influence in the same order of magnitude as the number of guards. In a context where monitoring is not carried out by the population, the frequency of meetings and the probability of denouncing a woodcutter have little influence.

| om_trees | om_stockMil | |

|---|---|---|

| probaDiscu | 0.59 | 0.72 |

| fréquenceRéu | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| tpsAuChamp | 0.29 | 0.16 |

| probaDenonce | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| nbProTGMax | 0.33 | 0.10 |

| qPrésenceBrousse | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| om_trees | om_stockMil | |

|---|---|---|

| nbProTGMax | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| tpsAuChamp | 0.29 | 0.22 |

| nbSurveillants | 0.20 | 0.29 |

| probaDiscu | 0.15 | 0.27 |

| qPrésenceBrousse | 0.15 | 0.10 |

| fréquenceRéu | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| probaDenonce | 0.00 | 0.02 |

Pattern Space Exploration

The PSE algorithm discretizes the model output space to systematically explore its diversity. We have configured it to retain only the results achieved in 95% of the simulation cases. The input parameters – shown in Table 3 – are left unrestricted to facilitate this exploration.

| Variables | Range |

|---|---|

| tpsAuChamp | (0.0, 100.0) |

| qPrésenceBrousse | (0.0, 1.0) |

| fréquenceRéu | (1.0, 10.0) |

| probaDenonce | (0.0, 100.0) |

| probaDiscu | (1.0, 100.0) |

| nbProTGMax | (5.0, 50.0) |

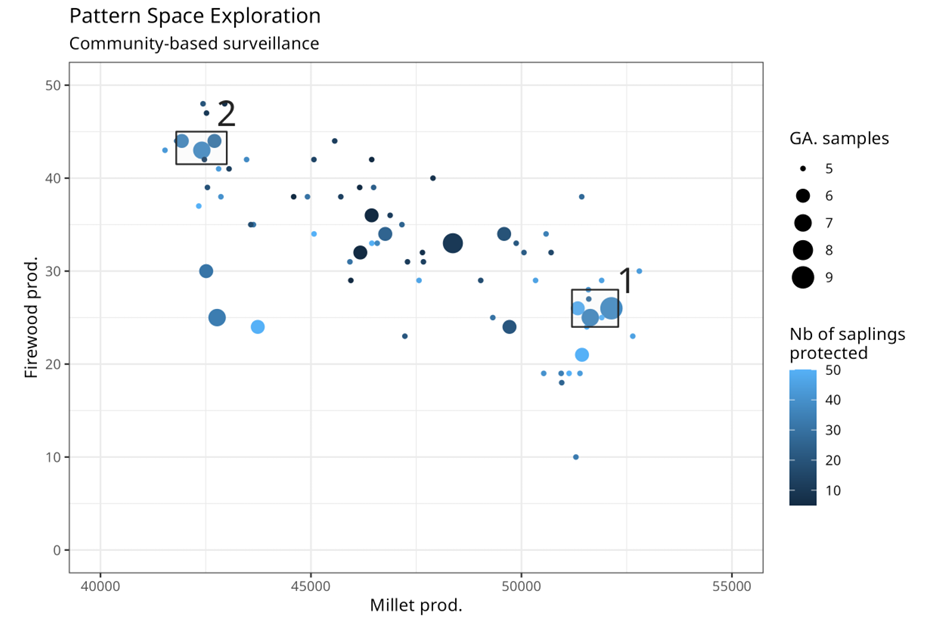

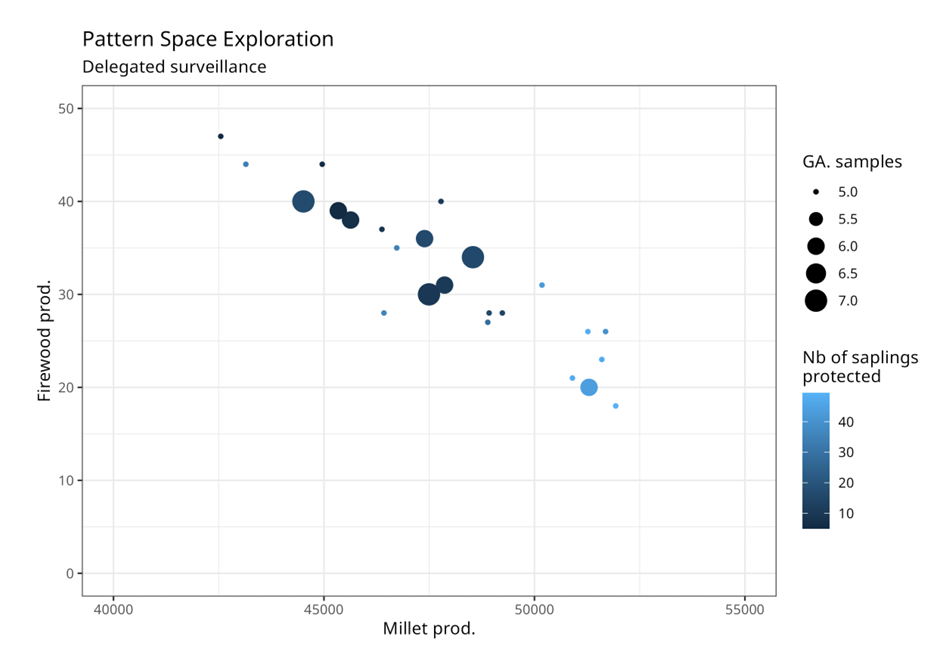

In Figures 5 and 6, we observe a negative relationship between millet production and firewood production. That is to say, the more we can harvest firewood, the less we can harvest millet.

Let us then look at the influence of the type of tree surveillance. By comparing the two scenarios, we can see that simulations reaching the numbered spaces 1 and 2 in Figure 5, representing community surveillance, are less present in Figure 6, which represents the delegated surveillance scenario. Conversely, on Figure 6, the model tends to easily reach intermediate situations (large, dark blue points).

The extremes framed in 1 and 2 in Figure 5 are associated with a high number of protected seedlings (\(nbProTGMax\)). This provides indications on the trajectories of the systems.

In both situations, reducing the harvesting of firewood leads to a higher number of seedlings. In both cases, these situations are reached by simulations where RNA and the diffusion of practices are present in the form of awareness meetings.

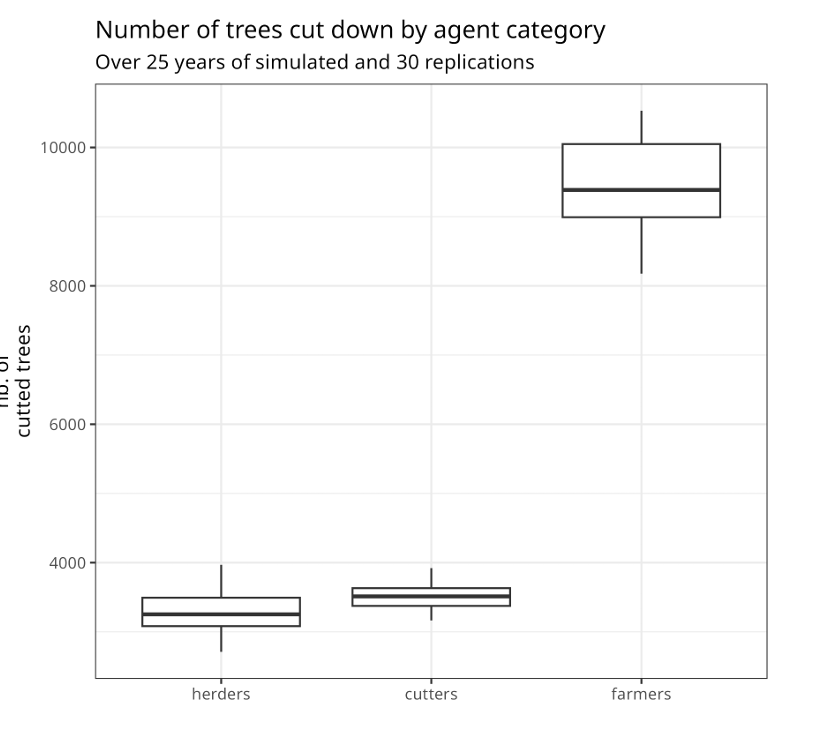

Unexpected yet attainable: Surprising results with minimal calculations

In the context of the co-construction of the simulation model, by integrating some basic indicators, we highlighted a fundamental issue that had never before been raised by the participants of the Living Lab as a major problem. By closely monitoring the total number of trees cut down, whether by herders for livestock, women for firewood, or farmers during their agricultural activities, a surprising trend emerged for participants (see Figure 7). This analysis revealed that farmers themselves significantly contribute to tree destruction, albeit in a somewhat silent manner (c.f. Figure 8). Specifically, this destruction often goes unnoticed because it takes the form of weeding very young plants, carried out by farmers without their full awareness. This result was extensively discussed during the workshop, which allowed for the clarification of farming techniques to ensure that the translation into the model was accurate. This observation challenges some previous perceptions and raises essential questions regarding the management of tree resources within the community.

Discussion

As we outlined in the introduction, our purpose here was to support discussions and the ability of stakeholders to make concerted decisions by using ComMod and ComExp. By adopting the "Different Modelling Purposes" from Edmonds et al. (2019), we position our intervention within two categories: illustration and social learning (Le Page & Perrotton 2017). Thus, we consider the process as a whole as the outcome (Etienne 2014), leading the involved populations to re-examine their management practices of space and natural resources, in order to nurture the socio-spatial relationships that are under stress (Selfa & Endter-Wada 2008).

The work we have conducted throughout this process allows us to discuss two dimensions: i) the elements of the numerical results directly derived from the model co-constructed with the participants, and ii) the transformative impact of the discussions that took place during the process, which have begun to change behaviors.

Discussion of numerical results

Our global sensitivity analysis (Tables 1 and 2) revealed critical insights into the dynamics of community surveillance scenarios. Specifically, we found that the likelihood of community discussions regarding the importance of trees significantly influences both millet production (with a sensitivity index of 0.72) and the overall number of trees (sensitivity index of 0.59). These results underscore the crucial role of active participation and awareness within the community. They suggest that integrating structured discussions about tree preservation into major life events, like traditional rituals, and daily interactions could enhance the effectiveness of community-based natural resource management. By formalizing these discussions, communities can better understand and address the ecological and social implications of their traditional and current land use practices.

In scenarios where surveillance is delegated to forestry guards, the dynamics of resource management shift noticeably. While the time spent in the field and the likelihood of discussions on tree preservation continue to be significant, the introduction of external surveillance personnel brings additional dynamics into play. Our analysis indicates that the presence of these agents decreases the frequency of community meetings and the likelihood of reporting illegal activities, suggesting a shift towards a more controlled but potentially less community-involved management system. This shift was evident in our Pattern Space Exploration (PSE) results (c.f. Figures 5 and 6), highlighting changes in community dynamics under different surveillance regimes.

Our PSE analysis has unveiled a notable negative correlation between millet production and firewood harvesting, regardless of the regulatory approach employed. The simulations that reached the extremes of this model output space demonstrated that reducing firewood harvest not only protects more young plants but also significantly boosts millet yields. This finding suggests that policies aimed at reducing wood harvest could simultaneously enhance agricultural productivity and biodiversity conservation, offering a dual benefit to the communities involved.

Driving transformation through companion modeling

Our study has illuminated practical solutions through the use of community surveillance, which has shown improvements in either conservation or agricultural productivity goals. However, these benefits require a significant time investment from the community. Effective community surveillance not only demands involvement but also a commitment to ongoing dialogues and actions. This investment in time and effort needs to be supported by the community, recognizing the long-term benefits in fostering sustainable practices and enhanced resource management.

During our research, we identified a critical issue previously unnoticed by participants of the Living Lab: the significant impact of agricultural practices on tree destruction (c.f. Figure 7). This destruction often goes unnoticed as it primarily involves the removal of young saplings during routine weeding, which is less dramatic than the felling of mature trees. The use of ploughs drawn by horses has eased the labour of farmers, yet has inadvertently led to the reduction of young trees. This oversight highlights the need for adapting agricultural practices to mitigate unintended environmental impacts.

The results of our study profoundly impacted the participants, prompting them to organize a community outreach day to share findings with neighbouring villages (c.f. Figure 9). Recognizing that the protection of trees cannot be managed effectively at an individual or single-community scale, participants developed proposals for collective action during this deliberative session. This initiative reflects a strong community awareness and a commitment to extending the scope of conservation efforts beyond their immediate environment.

Following this meeting, the participants involved in the development of the SAFIRe model expressed a strong desire to take concrete action in their own territory. They initiated campaigns to mark young tree seedlings in their fields to protect them from damage caused by soil cultivation tools (Figure 10). In addition, they established a community nursery for Faidherbia albida in preparation for the 2025 rainy season (Figure 11). The young trees will be transplanted into farmers’ plots at the onset of the first rains to promote successful rooting and establishment.

While we were able to continue tracing the social dynamics around trees as they gathered momentum in Diohine, new community nursery initiatives began to emerge in neighboring villages (Diarere). These offshoots signal more than simple replication – they mark a shifting collective awareness, a transformation in ways of relating to land, trees, and futures. What we are witnessing is not a top-down diffusion, but a situated, entangled process of becoming-with trees, in which local actors reconfigure their roles and responsibilities in response to shared concerns about regeneration and care.

Conclusion

This research began by identifying the aspirations of local populations, from which local stakeholders selected priorities. Among these aspirations, the desire for a restored environment was paramount, manifesting in efforts to increase tree populations, particularly of Faidherbia albida.

Building on this aspiration, we collaborated with local communities through multiple workshops to develop an agent-based model. This model serves not just as a scientific tool but as a reflection of the community’s perceived critical relationships and strategies necessary to achieve their environmental goals. This process melds scientific experimentation with co-construction and exploratory companion modeling, ensuring that the model’s outcomes are deeply rooted in both empirical research and community insights.

The results of the model should be viewed within the trajectory of the community group, indicating that they encapsulate the relationships the group deemed essential for realizing their aspirations. These results highlight collective opportunities for improving tree counts in the area but also expose contradictions, such as the competing need for firewood for cooking.

This conflict suggests that in addition to protecting young saplings, it is crucial to promote alternatives to firewood, such as the use of improved stoves or Typha charcoal. Protecting and increasing tree numbers in the area primarily requires supporting farmers to identify and preserve young saplings in the fields until they reach maturity.

Although the practice of marking young tree saplings for protection exists, it is not sufficiently adopted. The use of simulation to orchestrate the system of interrelationships that the actors co-constructed has been instrumental in raising awareness about the importance of collective action. This awareness has led to the organization of deliberation days on the subject with neighbouring villages.

Engaging stakeholders in model exploration is an extremely powerful activity when aiming to encourage them to consider alternative futures. This participatory approach not only fosters a deeper understanding of the ecological and social dynamics at play but also empowers communities to actively participate in shaping their environmental futures.

Acknowledgments

We warmly thank the residents of Diohine for their hospitality, with special thanks to: Aissatou Faye, Robert Diatte, Pierre Faye, Paul Sene, Ameth Paul Thiaw, Assane Diouf, Guedj Diouf, Nicolas Diouf, Ablaye Faye, Idrissa Faye, Maire-Hélène Ndjira Diouf, Seynabou Gakou, Joseph Sene, Ndeye Thiamal. The research was conducted withing DSCATT project (Dynamics of Soil Carbon Sequestration in Tropical and Temperate Agricultural Systems), financed by Agropolis Fondation (on "Programme Investissement d’Avenir" Labex Agro, financing ANR-10-LABX-001-01) and by Fondation TOTAL as part of a sponsorship agreement.

Funding

This work is part of the research and development project DSCATT (Dynamics of Soil Carbon Sequestration in Tropical and Temperate Agricultural Systems, https://dscatt.net/FR/index.html) co-funded by Agropolis Fondation [reference ID 1802-001] through the "Investissements d’avenir" program Labex Agro [ANR-10-LABX-0001-01] within the framework of I-SITE MUSE [ANR-16-IDEX-0006] and supported by the TOTAL Energies Foundation.

Notes

- All information about OpenMole can be found here: https://openmole.org/↩︎

- This manual page describing the operation of the algorithm, consulted on June 5 2024: https://openmole.org/PSE.html↩︎

References

AUDOUIN, É., Vayssières, J., Bourgoin, J., & Masse, D. (2018). Identification de voies d’amélioration de la fertilité des sols par atelier participatif. In V. Delaunay, A. Desclaux, & C. Sokhna (Eds.), Niakhar, Mémoires et Perspectives: Recherches Pluridisciplinaires sur le Changement en Afrique (pp. 337–371). Dakar: IRD Éditions. [doi:10.4000/books.irdeditions.31712]

BA, M., Bourgoin, J., Thiaw, I., & Soti, V. (2018). Impact des modes de gestion des parcs arborés sur la dynamique des paysages agricoles, un cas d’étude au Sénégal. VertigO, 18(2). [doi:10.4000/vertigo.20397]

BANOS, A. (2010). La simulation à base d’agents en sciences sociales: Une "béquille pour l’esprit humain" ? Nouvelles Perspectives en Sciences Sociales: Revue Internationale de Systémique Complexe et d’études Relationnelles, 5(2), 91–100. [doi:10.7202/044078ar]

BARRETEAU, O., Antona, M., D’Aquino, P., Aubert, S., Boissau, S., Bousquet, F., Daré, W., Etienne, M., Le Page, C., Mathevet, R., Trébuil, G., & Weber, J. (2003). Our companion modelling approach. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 6(2), 1.

BECU, N., Neef, A., Schreinemachers, P., & Sangkapitux, C. (2008). Participatory computer simulation to support collective decision-making: Potential and limits of stakeholder involvement. Land Use Policy, 25(4), 498–509. [doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.11.002]

BIERSCHENK, T., & Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. (1994). ECRIS: Enquête collective rapide d’Identification des conflits et des groupes stratégiques. Bulletin de l’APAD, 7. [doi:10.4000/apad.2173]

BOMMEL, P. (2009). Définition d’un cadre méthodologique pour la conception de modèles multi-agents adaptée à la gestion des ressources renouvelables. PhD Thesis, Montpellier 2.

BOSERUP, E., & Chambers, R. (1965). The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure. London: Routledge. [doi:10.4324/9781315070360]

CESARO, J.-D., Mbaye, T., Ba, B., Ba, M. F., Delaye, E., Akodewou, A., & Taugourdeau, S. (2023). Reforestation and sylvopastoral systems in Sahelian drylands: Evaluating return on investment from provisioning ecosystem services, Senegal. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11. [doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1073124]

CHÉREL, G., Cottineau, C., & Reuillon, R. (2015). Beyond corroboration: Strengthening model validation by looking for unexpected patterns. PLoS One, 10(9), e0138212.

DE Kraker, J., Kroeze, C., & Kirschner, P. (2011). Computer moDEls as social learning tools in participatory integrated assessment. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 9(2), 297–309. [doi:10.1080/14735903.2011.582356]

DELAUNAY, V., Desclaux, A., & Sokhna, C. (2018). Niakhar, Mémoires et Perspectives: Recherches Pluridisciplinaires sur le Changement en Afrique. Dakar: l’Harmattan Sénégal IRD.

DELAY, E., Chapron, P., Leclaire, M., & Reuillon, R. (2020). ComExp: Une manière d’introduire l’exploration avec les acteurs. ComMod, Le Cauvel, France.

DELAY, E., Ka, A., Niang, K., Touré, I., & Goffner, D. (2022). Coming back to a commons approach to construct the Great Green Wall in Senegal. Land Use Policy, 115, 106000. [doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106000]

EDMONDS, B., Le Page, C., Bithell, M., Chattoe-Brown, E., Grimm, V., Meyer, R., Montañola-Sales, C., Ormerod, P., Root, H., & Squazzoni, F. (2019). Different modelling purposes. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 22(3), 6. [doi:10.18564/jasss.3993]

ETIENNE, M. (2014). Companion Modelling: A Participatory Approach to Support Sustainable Development. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

ETIENNE, M., Du Toit, D., & Pollard, S. (2011). ARDI: A co-construction method for participatory modeling in natural resources management. Ecology and Society, 16(1). [doi:10.5751/es-03748-160144]

GRIMM, V., Berger, U., Bastiansen, F., Eliassen, S., Ginot, V., Giske, J., Goss-Custard, J., Grand, T., Heinz, S. K., Huse, G., Huth, A., Jepsen, J. U., JNørgensen, C., Mooij, W. M., Müller, B., Pe’er, G., Piou, C., Railsback, S. F., Robbins, A. M., … DeAngelis, D. L. (2006). A standard protocol for describing individual-based and agent-based models. Ecological Modelling, 198(1), 115–126. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.04.023]

GRIMM, V., Berger, U., DeAngelis, D. L., Polhill, J. G., Giske, J., & Railsback, S. F. (2010). The ODD protocol: A review and first update. Ecological Modelling, 221(23), 2760–2768. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.08.019]

GRIMM, V., Railsback, S. F., Vincenot, C. E., Berger, U., Gallagher, C., DeAngelis, D. L., Edmonds, B., Ge, J., Giske, J., Groeneveld, J., Johnston, A. S. A., Milles, A., Nabe-Nielsen, J., Polhill, J. G., Radchuk, V., Rohwäder, M. S., Stillman, R. A., Thiele, J. C., & Ayllón, D. (2020). The ODD protocol for describing agent-based and other simulation models: A second update to improve clarity, replication, and structural realism. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 23(2), 7. [doi:10.18564/jasss.4259]

HE, S., Yang, L., & Min, Q. (2020). Community participation in nature conservation: The Chinese experience and its implication to national park management. Sustainability, 12(11), 4760. [doi:10.3390/su12114760]

INGOLD, T. (2005). Epilogue: Towards a politics of dwelling. Conservation and Society, 3(2), 501–508.

LE Page, C., & Perrotton, A. (2017). KILT: A modelling approach based on participatory agent-Based simulation of stylized socio-ecosystems to stimulate social learning with local stakeholders. In G. Sukthankar & J. A. Rodriguez-Aguilar (Eds.), Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (Vol. 10643, pp. 31–44). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71679-4_3]

MARASENI, T. N., Bhattarai, N., Karky, B. S., Cadman, T., Timalsina, N., Bhandari, T. S., Apan, A., Ma, H. O., Rawat, R. S., Verma, N., San, S. M., Oo, T. N., Dorji, K., Dhungana, S., & Poudel, M. (2019). An assessment of governance quality for community-based forest management systems in Asia: Prioritisation of governance indicators at various scales. Land Use Policy, 81, 750–761. [doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.044]

MBOW, C., Brandt, M., Ouedraogo, I., De Leeuw, J., & Marshall, M. (2015). What four decades of Earth observation tell us about land degradation in the Sahel? Remote Sensing, 7(4), 4048–4067. [doi:10.3390/rs70404048]

PELISSIER, P. (1966). Les Paysans du Sénégal: Les civilisations agraires du Cayor à la Casamance. Fabrègue.

PERROTTON, A., Ba, M., Delay, E., & Fallot, A. (2021). Définition collective d’un futur désirable pour la zone de Diohine, Sénégal: Implementation de la méthode ACARDI à Diohine au Sénégal. [doi:10.1051/cagri/2025029]

PIERI, C. (1989). Fertilité des terres de savanes: Bilan de trente ans de recherche et de développement agricoles au sud du Sahara. Ministère de la Coopération et du Développement [u.a.], Paris.

R Core Team. (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

REUILLON, R., Leclaire, M., & Rey-Coyrehourcq, S. (2013). OpenMOLE, a workflow engine specifically tailored for the distributed exploration of simulation models. Future Generation Computer Systems, 29, 1981–1990. [doi:10.1016/j.future.2013.05.003]

ROUPSARD, O., Audebert, A., Ndour, A. P., Clermont-Dauphin, C., Agbohessou, Y., Sanou, J., Koala, J., Faye, E., Sambakhe, D., Jourdan, C., le Maire, G., Tall, L., Sanogo, D., Seghieri, J., Cournac, L., & Leroux, L. (2020). How far does the tree affec the crop in agroforestry? New spatial analysis methods in a Faidherbia parkland. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 296, 106928. [doi:10.1016/j.agee.2020.106928]

SALTELLI, A., Ratto, M., Andres, T., Campolongo, F., Cariboni, J., Gatelli, D., Saisana, M., & Tarantola, S. (Eds.). (2008). Global Sensitivity Analysis: The Primer. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [doi:10.1002/9780470725184]

SAQALLI, M., Bielders, C. L., Gerard, B., & Defourny, P. (2009). Simulating rural environmentally and socio-economically constrained multi-activity and multi-decision societies in a low-data context: A challenge through empirical agent-based modeling. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 13(2), 1. [doi:10.18564/jasss.1547]

SELFA, T., & Endter-Wada, J. (2008). The politics of community-based conservation in natural resource management: A focus for international comparative analysis. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(4), 948–965. [doi:10.1068/a39160]

SIEVERT, C. (2020). Interactive Web-Based Data Visualization with R, plotly, and shiny. London: Chapman and Hall/CRC. [doi:10.1201/9780429447273]

SPELKE Jansujwicz, J., Calhoun, A. J. K., Hutchins Bieluch, K., McGreavy, B., Silka, L., & Sponarski, C. (2021). Localism “reimagined”: Building a robust localist paradigm for overcoming emerging conservation challenges. Environmental Management, 67(1), 91–108. [doi:10.1007/s00267-020-01392-4]

TAPPAN, G. G., Cotillon, S., Herrmann, S., Cushing, W. M., & Hutchinson, J. A. (2016). Landscapes of West Africa - A window on a changing world. Available at: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/landscapes-west-africa-a-window-a-changing-world

WILENSKY, U. (1999). NetLogo. Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling, Northwestern University. Evanston, IL. Available at: http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/