Effect of Network Homophily and Partisanship on Social Media to “Oil Spill” Polarizations

and

University of Tsukuba, Japan

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 29 (1) 1

<https://www.jasss.org/29/1/1.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5807

Received: 04-Apr-2025 Accepted: 05-Nov-2025 Published: 31-Jan-2026

Abstract

Recent research has been conducted on "oil spill polarization," whereby preferences for topics that are not inherently politically nuanced become polarized based on political identity. Previous studies that explored the mechanisms of oil spill polarization through simulations demonstrated that this phenomenon occurs among intense partisans. However, empirical studies have shown that oil spill polarization occurs even among the general public and individuals with relatively moderate partisan identities, indicating a divergence between the simulation results and the phenomena observed in reality. We hypothesize that this discrepancy might be because of network homophily, a phenomenon often observed in social media communication. To address this, we conducted experiments using a multi-agent simulation model that implements network construction based on homophily. Our findings indicate that, when network construction is based on homophily, oil spill polarization arises among moderate partisans and diverse partisans.Introduction

Social media and polarization

Polarization is a critical issue in modern communication environments. Polarization describes a situation wherein people’s opinions become more extreme particularly on certain binary or conflicting topics, leading to a division into groups with differing views (Sunstein 2007). Polarization has intensified over the years, especially on political topics (Gentzkow 2016). Intense polarization increases the conflict between people with differing views. Moreover, it makes constructive debate more difficult. Hence, extreme political polarization could threaten democratic societies (Ross Arguedas et al. 2022).

Communication via social media is a key factor in the recent increase in political polarization (Guess et al. 2018; Terren & Borge 2021). Social media’s pervasive spread has alleviated the geographical constraints and cost of communication for individuals. Hence, modern individuals can interact with others who share similar views more often (Bakshy et al. 2015).

Network homophily theory explains why people actively engage with others who share similar preferences (McPherson et al. 2001). According to this theory, individuals actively seek out and agree with opinions aligning with their preferences and avoid those that contradict their preferences (Klapper 1960). Social media communication is performed through an information network controlled by the user’s own follow relationships (Conover et al. 2012). Individuals are less likely to encounter information contradicting their existing beliefs and perspectives in such environments (Kwak et al. 2011; Sibona & Walczak 2011).

Communicating selectively with like-minded individuals leads to the intensification of their existing views and increased polarization of their preferences. Network homophily among individuals with similar preferences strengthens their existing opinions, potentially leading to more extreme views (Del Vicario et al. 2016). Repeated behavior reinforces increasingly extreme views, deepening divides between conflicting preferences. This is considered the mechanism by which polarization intensifies through communication via social media (Bright 2018).

Research on opinion polarization on social media has focused on political identities, often highlighting the conflicts between conservatives and liberals (Kubin & von Sikorski 2021). Polarization based on binary oppositions related to specific ideologies is more likely to escalate into an aggressive debate aimed at defeating the opposing side’s views instead of fostering constructive discussions aimed at negotiation (Jenke 2024; Wojcieszak & Warner 2020). This is known as “affective polarization”, where rhetoric that provokes stronger emotional reactions is more likely to be supported. Therefore, communication spheres where affective polarization occurs become better breeding grounds for conspiracy theories aimed at discrediting opposing factions and spreading sensationalized fake news (Bessi et al. 2015; Lelkes 2018).

Conspiracy theories and fake news extend beyond online communication spheres, causing significant harm in real-world society. In the 2016 US presidential election, the negative campaign against democratic candidate Hillary Clinton escalated into conspiracy theories. These conspiracies were driven by affective polarization and ultimately resulted in a shooting incident at a real-world establishment (Bleakley 2023). In the 2020 US presidential election, former President Trump’s supporters, believing in election-related fake news, attacked the US Capitol to protest alleged election fraud. These attackers mostly belonged to polarized information networks that amplified and over-interpreted Mr. Trump’s posts (Hitkul et al. 2021). Therefore, polarization stemming from political conflict has become increasingly worrying, and research on polarization remains active.

“Oil spill” polarization

Much polarization research has focused on cases based on the binary axis of political identity (e.g., conservative versus liberal). However, such conflicts do not emerge from political identity alone. Issues such as gun control, same-sex marriage, and abortion legalization are not inherently related to political identity. However, as these sensitive topics sometimes provoke strong arguments, they have often been used by political identity opponents for attacks (Conway 2021; Hunter 1991). The radicalization of discourse on sensitive topics in alignment with political identity has further polarized opinions and beliefs on these sensitive topics, which are now also frequently aligned with political beliefs (Conway 2021). Furthermore, political conflicts often intersect with issues that evoke intense emotions, possibly leading to affective polarization (Hunter 1991).

However, alignment with political identity is confirmed not only in sensitive “hot-button” topics. Lifestyle and consumption preferences that are less influenced by political factors – even preferences such as “liberals who prefer latte beverages” and “conservatives who prefer bird hunting” – are skewed to align with political identity.

The term “latte-liberal” has been coined to describe this problem (DellaPosta et al. 2015). This phenomenon has been observed in both beverages and sports and in music and movies. van Zoonen (2013) states that this phenomenon is more prevalent in today’s information society, where online personal identities are categorized based on various marketing information, making it easier for a wider range of preferences to be integrated into a single identity. DellaPosta (2020) described the extension of political identity-based conflicts into various lifestyles as “oil spill polarization”.

Polarization occurs when individuals with similar preferences for a particular topic are deeply involved with each other (Sunstein 2007). Polarization is problematic as it can exacerbate the existing divisions between individuals with differing viewpoints. This impedes constructive negotiation and compromise (Bright 2018). Conversely, “oil spill polarization” is problematic not because of the depth of people’s engagement with a topic but rather the wide expansion of the range of other topics to which they align with a particular topic (e.g., political identity). Rawlings & Childress (2024) indicates that not only drink preferences (e.g., lattes) but also a diverse array of lifestyle preferences (e.g., movies, sports, and music) are correlated with political identity. Additionally, DellaPosta (2020), in a time-series analysis of social survey data, found that various topics have become increasingly polarized over time, aligning with a particular topic preference (presumably political).

Moreover, this phenomenon has been observed in social media communication. Essig & DellaPosta (2024) revealed that networks of politically neutral terms in the Twitter (now X) biography closely align with those structured around political preferences. Social media can significantly amplify polarization, and this type of oil spill polarization could more extensively spread through communication on platforms (Bright 2018). Despite the mentioned studies having primarily focused on the US (with its two-party political system), the overlap between certain nonpolitical cultural and political clusters on social media has also been observed in regions with multiparty political systems (Kubin & von Sikorski 2021; Takikawa & Nagayoshi 2017).

The spill of political polarization into lifestyle preferences may further intensify affective polarization (Kobellarz et al. 2024; Westheuser & Zollinger 2025). As various lifestyle choices become associated with political affiliation, relatively insignificant differences may even become criteria for distinguishing allies from adversaries (Bednar 2021; Shook & Fazio 2009; Talaifar et al. 2025). In the 2024 US presidential election, the Republican politician JD Vance categorized democratic candidate Ms. Harris as a “Childless cat ladies”. This statement was made using a completely apolitical topic (e.g., preferences for animals), with the intention to undermine the opposing candidate by portraying them as an adversary (Kogan et al. 2024). This case can be considered an example of affective polarization becoming apparent because of the expansion of the political identity oil spill. These perceptions are observed not only among the general public but also among political elites.

Mechanism of “oil spill” polarization

Oil spill polarization of lifestyles is considered to occur as a result of cognitive changes based on Heider’s balance theory (Heider 1958). Consider a situation wherein individuals A and B have established a positive relationship based on political preference alignment. A prefers drinking lattes, whereas B dislikes them. In this case, A experiences cognitive dissonance on both B and lattes as their preference for drinking lattes conflicts with that of B, whom A considers a close acquaintance. In this case, A may adjust the balance of preferences toward the object by changing their perception of either B or lattes from a positive to a negative one. This is the concept of the cognitive balance theory.

Preference changes by cognitive balance theory occur on various topics, but political identity and hot-button topics are less susceptible to cognitive balance, and beliefs are more likely to be fixed (Goren & Chapp 2017). Thus, oil spill polarization is considered intensified by the cognitive balance theory among people with matching preferences for fixed political beliefs (DellaPosta et al. 2015).

Although cognitive balance theory concerns interactions between individuals, the agent-based simulations conducted by DellaPosta et al. (2015) have demonstrated that oil spill polarization occurs when this interaction occurs in many people. In this simulation experiment, the communication occurs so that among the connected individuals, those who have similar opinions about the agent’s own political preferences and other lifestyle preferences are more likely to be selected as communication targets. When there is cognitive dissonance on a lifestyle topic with an individual whose political preferences match, the agent achieves cognitive balance by changing some of their own lifestyle preferences to match those of their partner. In this case, political preferences and preferences on hot-button topics remain unchanged. The simulation of multiperson interactions based on this model demonstrates that the mutual cognitive balancing of agents leads to oil spill polarization based on political identity. Despite cognitive balance theory being a well-established social psychology model, this research has demonstrated that oil spill polarization can occur even in communication models based on a simple mechanism.

The DellaPosta et al. (2015) experiment used a fixed connected caveman graph. Therefore, it is not assumed that online communication does not have geographic limitations, as in modern social media. Hence, Törnberg (2022) examined an extended model that allowed communication targets, which were previously fixed, to vary randomly. Additionally, the model implemented a tolerance on the agents for others with different preferences. Low tolerance for others further limits the probability of communicating with others whose preferences do not align. The experiment revealed that, when agents have a low tolerance for those with differing preferences and the probability of communication targets being randomly swapped is high, polarization of preferences was observed on lifestyle topics in alignment with political preferences. Therefore, in an unfixed information network, oil spill polarization is because of the adjustment of cognitive balance among individuals with low tolerance for opposing viewpoints.

Challenges of previous research

Oil spill polarization on social media occurs in situations where information networks are highly random and tolerance for communication partners is low. However, the DellaPosta et al. (2015) and Törnberg (2022) models are subject to two limitations when considered in the context of contemporary social media communication and the occurrence of oil spill polarization.

The first issue is in network building. Törnberg (2022) conducted an experiment wherein the model reflects a setting in which information networks are swapped randomly. This model was designed to represent online communication, such as that which occurs on social media platforms, without geographical constraints. Section 1.1 showed that in actual social media environments, like-minded users construct fixed networks based on homophily (Cinelli et al. 2021; Khanam et al. 2023). Social media’s information networks are constructed by following relationships based on users’ own preferences. Hence, network homophily has a particularly significant effect (Conover et al. 2012). Therefore, an environment wherein information networks are randomly replaced even among people with already aligned preferences is considered an inadequate representation of the actual social media environment.

Second, oil spill polarization relies on individuals’ tolerance toward others. Agents’ intolerance to those with differing opinions is similar to that of individuals with strong political partisanship. Goren (2005) and Luttig (2018) demonstrated a correlation between individuals with low tolerance for differing preferences and strong partisan affiliation toward a specific political party.

However, oil spill polarization observed in real-world societies is not exclusive to individuals with strong partisanship. DellaPosta (2020) acknowledges that contentious issues (e.g., gun control and same-sex marriage), as argued by Baldassarri & Gelman (2008), are both more strongly partisan and divisive. Nevertheless, regarding other lifestyle-related oil spill polarization, they indicated that these attitudes are not exclusive to partisan groups but also prevalent among individuals with general political interests. Furthermore, Talaifar et al. (2025) found that even among individuals who do not hold strong stereotypes on lifestyle partisanship, they are more likely to associate a specific lifestyle with party preferences. This phenomenon has also been observed in social media communications. Praet et al. (2021) analyzed “like” networks on Facebook and found that the strength of partisanship had no effect on oil spill polarization in lifestyle-related pages with a low political component.

Hence, oil spill polarization occurring in practice is not limited to individuals with extreme views on partisan identity but also occurs among those with relatively moderate political preferences. However, existing models have demonstrated that oil spill polarization does not occur among such moderate individuals. This indicates a gap between these models and real-world oil spill polarization.

Aim of this paper

This study aims to clarify two issues. First, we aim to clarify whether oil spill polarization based on political preferences emerges when networks are built on agents’ homophily. Second, we aim to elucidate how the partisanship strength, equivalent to people’s tolerance for those with different preferences, affects oil spill polarization in networks based on homophily. Compared to previous studies, this study emphasizes network homophily in the context of social media, which has been identified as a key aspect of network building. If oil spill polarization occurs even among individuals with high tolerance for others and a moderate political identity when networks are constructed on homophily, then communication via social media may contribute to the ongoing oil spill polarization.

Methodology

Initial setup of the model

This experiment adopts multi-agent simulation based on the Törnberg (2022) model, as mentioned in Section 1.3. The Törnberg model is easy to adapt for building a homophily network based on agent preferences, which we’re examining in this study, because it already incorporates partner swapping. This also allows for a clear comparison between the results of random networking and homophily networking. We conducted the simulation in a two-dimensional lattice network space constructed with \(w\) vertices at each side. We placed agents at each vertex of the network. In the initial state, each agent is assigned the following group \(I\) comprising eight agents located in its Moore neighborhood. Each agent has two preferences types: one static preference \(S\) and \(N\) dynamic preferences \(D\).

Static preference \(S\) represents political preference. Each agent is randomly assigned a static preference of either conservative or liberal. Throughout the simulation, \(S\) remains unchanged. Each agent is randomly assigned a static preference of either conservative or liberal. This reflects that, as mentioned in Section 1.3, some preferences – such as for political ideologies – are not significantly influenced by others, even over time.

Dynamic preferences \(D\) represent various lifestyle-related preferences, including favorite types of music or sports teams. Lifestyle topics are considered to be more varied than political preferences, and the model implements \(N\) topics (set to 10 in this study), which is a greater number than \(S\). Unlike \(S\), \(D\) has the potential to fluctuate based on the cognitive balance adjustments from the communication between agents. Additionally, the preferences for topics of \(D\) are not necessarily binary. Hence, each agent can select one preference from \(L\) options (with \(L = 10\) fixed in this study) for each of their \(N\) dynamic preferences \(D\). In the initial setup of the simulation, reference \(D_{nl}\) (\(n \in N\), \(l \in L\)) for each topic in \(D\) is randomly assigned to each agent.

Moreover, each agent is assigned a strength of political partisanship. This factor is categorized into three types: “moderate”, “firm,” and “extreme” with the intensity of partisanship increasing from moderate to extreme. Partisanship intensity influences the partisan correction value \(a\) (see Section 2.6).

| \[a = 1 + \mathrm{random}[0, 2.0] \quad \text{if partisan = ``moderate''}\] | \[(1)\] |

| \[a = 3 + \mathrm{random}[0, 2.0] \quad \text{if partisan = ``firm''}\] | \[(2)\] |

| \[a = 5 + \mathrm{random}[0, 2.0] \quad \text{if partisan = ``extreme''}\] | \[(3)\] |

Modification of preferences because of others’ influence

In this simulation, an agent \(i\) is randomly selected at each step. Agent \(i\) selects one agent \(j\) from their following group \(I\), and it engages in communication with that user. In this case, the agent \(j\) selected by \(i\) is formulated based on a probability that is influenced by the similarity of attitudes between \(i\) and \(j\). In this model, “attitude” is represented as the overall set of an agent’s preferences. This encompasses both their static preference \(S\) and dynamic preferences \(D\).

At the current step \(t\), the similarity of attitudes \(\delta_{ij,t}\) between agents \(i\) and \(j\) is obtained from the following equation:

| \[ \delta^{S}_{ij} = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } S_i = S_j, \\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \qquad \text{and} \qquad \delta^{D}_{ij} = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } D_{i,l,t} = D_{j,l,t}, \\ 0, & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases}\] | \[(4)\] |

| \[ \delta_{ij,t} = \frac{a \, \delta^{S}_{ij} + \sum_{n \in \mathcal{N}} \delta^{D}_{ij,n,t}} {a + N}\] | \[(5)\] |

From Equations 4 and 5, the similarity \(\delta_{ij,t}\), increases as preferences of agent \(j\) align more closely with those of agent \(i\), both in terms of \(S\) and \(D\). From Equation 5, the static preference \(S\) is influenced by a correction factor \(a\). This is based on the intensity of the agent’s partisanship. Agents with more intense partisanship and larger \(a\) prioritize the alignment of static preferences \(S\) when calculating attitude similarity \(\delta_{ij,t}\).

Next, the probability \(p_{ij}\) of selecting agent \(j\) as communication partner is calculated based on \(\delta_{ij,t}\).

| \[ p_{ij,t} = \frac{\delta_{ij,t}^{a}}{\sum_{j \in I} \delta_{ij,t}^{a}}\] | \[(6)\] |

Equation 6 shows that the probability of selecting agent \(j\) increases as attitude similarity \(\delta_{ij,t}\) with agent \(i\) becomes larger. Equation 6 also shows that the correction value \(a\), based on the intensity of political partisanship, is implemented as a tolerance for agents with differing preferences. In this model, the more partisanship intensity and the larger the value of \(a\), the lower the probability that individuals with smaller attitude similarity will be selected as communication partners. This is based on previous findings (Goren 2005; Luttig 2018), suggesting that as partisanship intensifies, tolerance toward individuals with differing preferences decreases.

If preference value \(l\) (\(l \in L\)) within the dynamic preference \(D_{n}\) (\(n \in N\)) between \(i\) and \(j\) is different, agent \(i\) will adjust by modifying one of those \(D_{inl}\) \((D_{inl} \neq D_{jnl})\) via cognitive balance adjustment. If, for all \(D_{n}\), \(D_{inl}\), and \(D_{jnl}\) are consistent, \(i\) will not adjust their own preference.

Updating the following group based on network homophily

Immediately after the process in Sections 2.5-2.10, \(i\) updates the members included in \(i\)’s following group \(I\). The updating methods include two approaches: random matching and homophily matching.

In random matching, members of \(I\) are updated randomly based on probability, similar to Törnberg (2022) model. Before the preferences are modified in Sections 2.5-2.10, each agent \(j\) included in \(I_{i}\) is swapped with another random agent with a probability of \(\gamma\).

In homophily matching, the members of \(I_{i}\) are updated based on their similarity in preferences with \(i\). This simulates network management based on homophily in actual social media platforms (e.g., unfollowing or blocking others with conflicting attitudes). If there is an agent \(j\) in the members of \(I_{i}\) whose similarity \(\delta_{ij,t}\) is below the partisanship threshold \(\{a/10\}\), one of them will be unfollowed. Therefore, if the intensity of partisanship \(a\) is low, a follow relationship can be maintained with different-minded users. However, if \(a\) is high, a stable follow relationship cannot be established unless preferences align on many topics across \(S\) and \(D\). This method is based on the argument in previous studies (Peralta et al. 2024) that partisanship strength is correlated with the tolerance for individuals with differing preferences.

Additionally, when \(i\) unfollows an agent in the homophily matching, \(i\) selects another agent to follow. This ensures a fixed number of members in the following group, maintaining the simulation environment. In this case, the new agent \(k\) selected as the new follow target is randomly chosen from those whose preference value \(l\) matches at least one topic in \(S\) or \(D\) of agent \(i\). If no such agent is found, another is randomly selected from all agents to be chosen as the follow target. This method considers the recommendation feature of social media platforms, which suggests users with similar preferences based on the user’s own preferences.

Measuring “oil spill” polarization

This simulation experiment repeats the processes of preference updating (in Sections 2.5-2.10) and following group updating (in Sections 2.11-2.14). It stops when either the simulation step count reaches upper limit \(T\) or no change in the dynamic preferences of all agents is found over the last 10 communication rounds. At simulation end, we evaluate how much other dynamic preferences have polarized in alignment with the static preferences. First, for the evaluation, we calculate \(d_{ij}\) using Equation 7. This represents the degree of alignment in dynamic preferences \(D\) between any two agents.

| \[ d_{ij} = \frac{\sum_{n \in N} \delta_{ij,n,T}^{D}}{N}\] | \[(7)\] |

In this study, following Törnberg (2022), we use \(\psi\), defined as the difference \(Q_{same}\) (\(Q_{same} = \{ d_{ij} \mid i,j \in w^{2}; i \neq j; S_{i} = S_{j} \}\)\(d_{ij}\) for agents with matching static preferences \(S\) minus \(Q_{diff}\) (\(Q_{diff} = \{ d_{ij} \mid i,j \in w^{2}; i \neq j; S_{i} \neq S_{j} \}\)) \(d_{ij}\) for agents without matching \(S\), as an evaluation metric for oil spill polarization.

| \[ \psi = \frac{\sum Q_{same}}{|Q_{same}|} - \frac{\sum Q_{diff}}{|Q_{diff}|}\] | \[(8)\] |

\(\psi\) reaches a maximum value of 1.0 when agents with the same \(S\) share all \(D_{nl}\) values and do not share any \(D_{nl}\) values with agents who have different \(S\). Additionally, \(\psi\) takes 0.0 when all agents share the same \(D_{nl}\) values, regardless of their \(S\) values. Essentially, the closer \(\psi\) is to 1.0, the more the dynamic preferences \(D\) related to the lifestyle of all agents are in oil spill polarization relative to \(S\). Conversely, the closer \(\psi\) is to 0.0, the more it indicates either a state where \(D_{nl}\) is uniformly shared by all agents or a situation where many agents, regardless of their political preferences, maintain own lifestyle.

Results

Experimental conditions

The simulation sphere comprises a \(14 \times 14\) toroidal lattice network. We set the simulation parameters to align with conditions from Törnberg (2022), with the total number of agents \(w^{2} = 196\), a step limit of \(T = 1000000\), the number of dynamic preference topics \(N = 10\), and the number of dynamic preference types \(L = 10\).

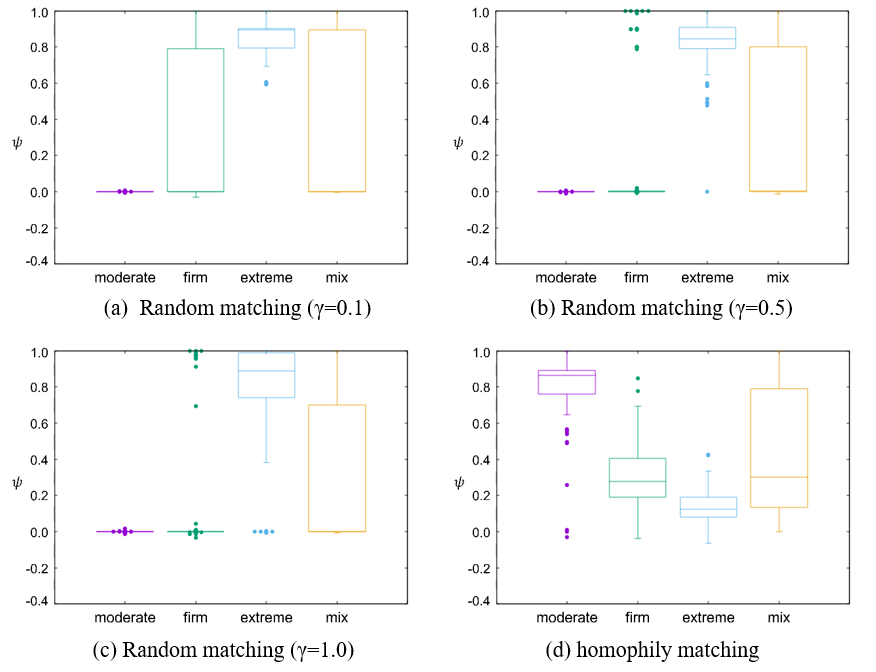

Under these conditions, we conducted experiments in two scenarios: random matching and homophily matching. In random matching, we examined three conditions based on followee swapping probability: low probability (\(\gamma= 0.1\)), moderate probability (\(\gamma= 0.5\)), and full followee replacement (\(\gamma= 1\)). For each scenario, we evaluated four patterns of agent partisanship intensity: (1) “moderate”, (2) “firm”, (3) “extreme”, and (4) “mixed”. In (4) “mixed”, the agents’ partisanship is randomly selected from “moderate”, “firm”, and “extreme”. Here, we compare and evaluate the oil spill polarization rate, \(\psi\), under each condition. We then present the results regarding the conditions under which oil spill polarization occurs.

Figures 1a-c show the distribution of \(\psi\) at the end of 100 simulations under each condition for random matching. The vertical axis represents the \(\psi\) values, while the horizontal axis shows the conditions related to agents’ partisanship. In all of (a) through (c), the condition wherein all agents have extreme partisanship demonstrates a high value of oil spill polarization, \(\psi\). Furthermore, as \(\gamma\) increases and the agents’ followed swapping more frequently, oil spill polarization rate tends to stabilize at a higher value. In this experiment, agents with extreme partisanship had lower tolerance toward others with different preferences. Therefore, the pattern observed by Törnberg (2022) was confirmed in this experiment, showing that agents with lower tolerance toward others and frequent interaction with others lead to the progression of oil spill polarization. Conversely, in the case of homophily matching as in Figure 1d, the highest \(\psi\) value is observed when the agents’ partisanship is moderate. Moreover, in the cases of firm and mix, oil spill polarization occurs less frequently in homophily matching compared to random matching. While extreme partisanship was a condition for high \(\psi\) in random matching, it remained stable at a lower value in homophily matching. This suggests that, in a situation where users follow others based on network homophily, the results directly oppose those observed in an environment where followers are randomly swapped.

Table 1 presents the mean and variance of \(\psi\) as well as \(Q_{same}\) and \(Q_{diff}\) values used to calculate \(\psi\). In random matching, the \(\psi\) values were low under the moderate, firm, and mix conditions. Conversely, both \(Q_{same}\) and \(Q_{diff}\) showed high values in all cases. Therefore, the dynamic preferences are aligned with the preferences of those who share the same static preferences and those who do not. In this scenario, as most agents share the same dynamic preferences, oil spill polarization based on specific partisanship does not occur. In the extreme condition, as the probability \(\gamma\) (swapping followers rate) increases, \(Q_{diff}\) decreases. Thus, as \(\gamma\) increases, the dynamic preference alignment with users who have different static preferences decreases, leading to an increase in \(\psi\).

Meanwhile, under homophily matching, the decrease in \(Q_{diff}\) in the moderate condition led to increased oil spill polarization rate \(\psi\), rising to about 80% compared to random matching. In the firm condition, \(Q_{diff}\) decreased compared to random matching. However, as \(Q_{same}\) also decreased simultaneously, \(\psi\) increased to around 40%. In the mix condition, both \(Q_{same}\) and \(Q_{diff}\) presented values between those of the moderate and firm conditions, with \(\psi\) also aligning at an intermediate value of approximately 43%. Conversely, while extreme partisanship exhibited a strong oil spill polarization rate of over 80% in random matching, \(Q_{same}\) significantly decreased in homophily matching. Therefore, dynamic preference alignment was no longer observed among same-static-preference users.

| moderate | firm | extreme | mix | |||||||||

| \(\psi\) | \(Q_{same}\) | \(Q_{diff}\) | \(\psi\) | \(Q_{same}\) | \(Q_{diff}\) | \(\psi\) | \(Q_{same}\) | \(Q_{diff}\) | \(\psi\) | \(Q_{same}\) | \(Q_{diff}\) | |

| Random | 0.000 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.134 | 0.991 | 0.857 | 0.793 | 0.997 | 0.204 | 0.280 | 0.996 | 0.715 |

| (\(\gamma=0.1\)) | (.003) | (.024) | (.024) | (.332) | (.022) | (.337) | (.264) | (.012) | (.264) | (.413) | (.012) | (.416) |

| Random | 0.000 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.156 | 0.997 | 0.841 | 0.827 | 0.994 | 0.167 | 0.353 | 0.994 | 0.641 |

| (\(\gamma=0.5\)) | (.002) | (.018) | (.018) | (.345) | (.011) | (.344) | (.160) | (.019) | (.159) | (.424) | (.016) | (.424) |

| Random | 0.000 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.295 | 0.990 | 0.695 | 0.851 | 0.997 | 0.147 | 0.342 | 0.997 | 0.665 |

| (\(\gamma=1.0\)) | (.002) | (.009) | (.010) | (.408) | (.037) | (.407) | (.111) | (.010) | (.110) | (.432) | (.010) | (.433) |

| Homophily | 0.803 | 0.970 | 0.167 | 0.309 | 0.397 | 0.089 | 0.136 | 0.239 | 0.102 | 0.426 | 0.553 | 0.126 |

| (.193) | (.095) | (.173) | (.172) | (.162) | (.049) | (.090) | (.088) | (.041) | (.335) | (.349) | (.118) | |

Discussion

This study aims to examine how the partisanship strength and the associated level of tolerance toward others affect oil spill polarization when communication networks on social media are constructed based on homophily. Through experiments in scenarios where following relationships were constructed based on network homophily, we found that oil spill polarization can occur even among agents without extremely strong partisanship. Oil spill polarization affects not only those with strong partisan identities but also the general public (DellaPosta 2020), including those with relatively neutral political stances (Talaifar et al. 2025). This study provides mathematical simulations to support the robustness of phenomena identified in previous studies. Here, we discuss the mechanism behind these results for each condition of agent political partisanship.

Moderate

“Moderate” refers to a state where all agents have weak partisanship, allowing some interaction with those holding different preferences. In random matching, agents’ followees are randomly swapped, regardless of preferences. Therefore, agents with different static preferences may appear in each other’s following group. In this study, the partisanship strength is associated with tolerance toward others with differing preferences. Thus, moderate agents are more likely to engage in interactions with individuals who hold differing opinions. Furthermore, when an agent interacts with another holding a different dynamic preference, the agent adjusts their dynamic preference to align with the other agent through cognitive balance theory. In the moderate condition, this alignment occurs even between users with different static preferences. This leads to dynamic preferences aligning across most agents, regardless of their static preferences. Consequently, both \(Q_{same}\) and \(Q_{diff}\) increase, indicating that oil spill polarization does not occur, similar to Törnberg (2022).

In homophily matching, agents can maintain a fixed follow relationships with those sharing their preferences align with their own. Random matching may exclude users whose preferences align from the following group. However, agents can maintain follow relationships with such users in homophily matching. Moderate agents, tolerant of different opinions, more easily maintain fixed follow relationships. Additionally, in this model, moderate agents also tend to prioritize the alignment of static preferences, albeit with limited intensity. Consequently, users with similar static preferences are more likely to construct stable networks. Consequently, the stable group of users with similar static preferences influences each other. This leads to an increase in \(Q_{same}\). However, when preferences align to some extent, the probability of swapping in the following group decreases. This leads to fewer interaction opportunities with agents holding different static preferences compared to random matching. Consequently, there are fewer opportunities to align dynamic preferences through interactions with agents holding different static preferences. This leads to a decrease in the \(Q_{diff}\) value compared to the random matching scenario. This suggests that oil spill polarization occurred among the moderate agents.

Firm

The firm condition represents agents with higher partisanship than moderate but lower than extreme. In random matching, similar to the moderate condition, agents can influence each other’s dynamic preferences through interactions with individuals holding different preferences. Therefore, both \(Q_{same}\) and \(Q_{diff}\) remain high, reducing the likelihood of oil spill polarization.

In the homophily matching scenario, both \(Q_{same}\) and \(Q_{diff}\) are lower compared to the moderate condition, with an oil spill polarization rate of 40%. Firm agents, compared to moderate agents, prioritize aligning of static preferences and have lower tolerance for differing preferences. Hence, firm agents will have difficulty establishing fixed follow relationships with those who have conflicting static preferences on homophily, limiting their interactions to individuals with shared similar static preferences. This is considered to be the reason for the decrease in \(Q_{diff}\).

Additionally, the lower tolerance of firm agents toward differing preferences leads them to interact more with agents within their follow network who have relatively high dynamic preference alignment and similar overall attitudes. Firm agents tend to engage more closely with those whose specific attitudes match, unlike moderate agents who align dynamic preferences with all agents within their follow network. They are thus less likely to interact with others based solely on static preferences. Consequently, it is unlikely that the cognitive balance adjustment caused all dynamic preferences to match among agents with the same static preferences. This is thought to have reduced \(Q_{same}\).

Extreme

Extreme agents have extremely high partisanship, prioritize aligning static preferences, and show low tolerance for differing preferences. Consequently, they have limited interactions with agents holding different stating preferences from their own. Therefore, in random matching, they primarily interact with users whose static preferences align. In this scenario, extreme agents interact almost only with users who share the same static preferences. This enhances \(Q_{same}\) through dynamic preference adjustments and reduces \(Q_{diff}\) by avoiding interactions with others holding conflicting static preferences. This suggests a high likelihood of oil spill polarization.

In homophily matching, extreme agents are less likely to construct fixed follow relationships with diverse agents compared to moderate or firm agents. They have a high preference adjustment value \(a\). In this model, maintaining a follow relationship requires the attitude similarity \(\delta_{ij,t}\) between agents and exceed the threshold \(a\). Hence, extreme agents can construct stable follow relationships only with users who share a high degree of similarity in both static and dynamic preferences. For instance, simply sharing the same static preferences, such as a conservative stance, may not adequately surpass the threshold \(a\). Instead, additional alignment on other topics, such as being conservative and opposing gun control, becomes necessary. That is, alignment in static preferences alone is insufficient to establish stable relationships.

However, if extreme agents manage to overcome these stringent conditions and form stable relationships with one another, they will exhibit exceptionally high similarity in their attitudes. The probability of interaction between the agents is calculated based on this similarity; extreme agents are subject to an additional adjustment determined by high \(a\). Hence, extreme agents primarily interact only with those agents with whom they have successfully constructed stable follow relationships. Consequently, widespread oil spill polarization based on static preferences does not occur. Instead, only intense communication occurs within a small, narrowly defined group of members whose preferences closely align. Such communication is a trait of political polarization, which has been mentioned in previous studies. Consequently, these conditions increase severe polarization and conspiracy theory risks.

Mix

In the mix condition, agents are randomly assigned an intense partisanship, which can be either moderate, firm, or extreme. Under these conditions, the results tended to vary depending on the initial state and the swapping of followees, leading to significant fluctuations in the data patterns across both random matching and homophily matching. However, in both scenarios, the median tends to be closer to the firm case. This indicates that the situation is generally somewhere between moderate and extreme.

In the mix state, under homophily matching, extreme agents only interact with agents who have high similarity in both static and dynamic preferences. Conversely, moderate and firm agents construct stable follow relationships and engage in interactions with extreme agents through weak ties based on the similarity of matching static preferences. Consequently, this combination of high \(Q_{same}\) from moderate agents and low \(Q_{diff}\) from extreme and firm agents leads to a higher oil spill polarization rate compared to random matching.

Considering that real-world social media environments are composed of individuals with diverse partisan intensities, considering this mixed state as the most representative of reality is reasonable. According to DellaPosta (2020), the correlation of other topics based on political ideology (and related beliefs) was approximately 40% in 2010. The average rate of oil spill polarization based on the static preferences for other topics in the mixed state of this experiment was 42.6%. Although slightly higher, the results of this experiment are generally considered to reflect values close to those observed in reality.

Conclusion

This paper examined how the effects of network homophily on social media influence oil spill polarization in the lifestyles of the general public, particularly those who are relatively neutral and more tolerant of differing opinions. To investigate this, we constructed a MAS model in which political identity is defined as a fixed static preference, whereas lifestyle-related preferences are represented as dynamic preferences that fluctuate through communication. We conducted a simulation experiment using this model to investigate whether oil spill polarization spreads among agents in their dynamic lifestyle preferences based on their political preferences.

Our results showed that the construction of networks through homophily leads to oil spill polarization among individuals with moderate partisanship, that is, those with tolerance for others with different preferences. Furthermore, oil spill polarization was observed in communication spaces where individuals with diverse partisanship co-exist. These findings support empirical research suggesting that oil spill polarization occurs not only among individuals with extreme political partisanship but also among those with neutral stances, as well as within the broader public composed of individuals with diverse partisanship (DellaPosta 2020; Rawlings & Childress 2024; Talaifar et al. 2025).

Notably, under conditions where network homophily occurs, oil spill polarization was primarily prevented among individuals with moderate partisanship. Moreover, among people with extreme partisanship oil spill polarization is less likely to occur. In our model, which is based on the concept of network homophily, an agent establishes the following relationship with others when the overall attitudinal similarity, which comprises both static and dynamic preferences, exceeds the agent’s own threshold. The threshold for maintaining the following relationship is dependent upon the strength of the agent’s partisanship. This partisanship-based threshold variation may have affected the agents’ selection of communication targets and influenced the prevalence of oil spill polarization.

Individuals who hold moderate partisanship are more tolerant of those with differing opinions and thus have a lower threshold for similarity in preferences regarding the following relationship. Hence, when the condition of matching static preferences is fulfilled, it is possible to exceed the threshold of the following relationship. Consequently, it is more straightforward to establish fixed-following relationships based on the static preference alignment. Furthermore, moderate partisans are tolerant of others who hold differing preferences. Therefore, they have opportunities to communicate with others who have relatively low preference alignment and are susceptible to influence on various dynamic topics through cognitive balance adjustment. This repetition among people in fixed-following relationships based on alignment of static preferences may have allowed oil spill polarization to spread widely among those with the same static preferences. Therefore, oil spill polarization can be considered to spread through a network of weak ties, based on static partisanship alignment via social media. Rawlings & Childress (2024) showed through social surveys that oil spill polarization occurs in various lifestyles surrounding political polarization. However, these phenomena are not intense conflicts between individuals with extreme political beliefs. Rather, they are “shallow and wide” when partisanship is the axis of analysis. The results of this study support the findings of this empirical investigation.

Meanwhile, individuals with extreme partisanship who are less tolerant of others have a higher threshold for establishing the following relationship. Therefore, in contrast to individuals with moderate partisanship, a fixed relationship cannot be established on the basis of a mere alignment between static preferences. Conversely, other individuals who surpassed these thresholds aligned not only with the static preferences but also with multiple aspects of the dynamic preferences. Individuals with extreme partisanship tend to have lower levels of tolerance for those with differing preferences. This, in turn, reduces the probability of communication with those who hold differing views. Therefore, individuals with extreme partisanship do not engage in communication that could potentially influence them to alter their own preferences. Instead, they tend to communicate with others whose preferences align closely with their own. Consequently, a comprehensive alignment of the dynamic preferences based on the matching of the static preferences is improbable. However, a sectarian discourse will emerge among those with narrowly aligned static and dynamic preferences. This phenomenon of opinion radicalization through deep communication within a narrow range is analogous to the concept-based polarization that has previously been identified as a cause for concern (Diaz Ruiz & Nilsson 2023).

This study suggests oil spill polarization among people with neutral political positions and the general public may depend on the construction of communication networks based on homophily, as in social media. Polarization research often focuses on communication among people with strong partisanship owing to their significant social influence (Guess et al. 2018). However, oil spill polarization, which is considered one factor in intensely affective polarization, may involve broad networks formed by simply static preference alignment among the general public and moderates. This study highlights the risk that communication among the general public on social media could also contribute to polarization.

Finally, we outline some of the limitations and remaining challenges of this experiment to offer guidance for future research. This study was conducted with the objective of examining the effects of network homophily observed in social media communication by comparing them with previous research. Consequently, it was necessary to approximate the previous research except for the network construction rules. Therefore, it should be noted that this model is a kind of idealized one, and there are parts of it that do not account for the characteristics of actual social media communication.

For instance, our model’s design is based on a primitive social media platform where users can only interact with those they follow. However, modern social media platforms have a mechanism that shows users posts from others they do not follow, based on their preferences. Additionally, it is considered that the selection of preferences on topics is influenced by various external factors beyond their innate preferences. Demographic factors such as family background, geographic location, education, and income shape the cultural exposure of individuals (Bourdieu & Passeron 1990; Kiley & Vaisey 2020).

These factors are expected to influence oil spill polarization. However, considering too many new factors would make it difficult to compare our results with those of previous studies. Hence, we did not include these factors in this study. In the future, to conduct simulations that more closely approximate real-world phenomena, it will be necessary to incorporate these factors and develop a model that can reproduce actual data.

Next, we outline several challenges related to the topic. In this study, political identity is assigned to a static topic that does not change because of influences from others. However, it is considered a common situation that some individuals fix their identity to preferences regarding topics other than political identity. That is, political identity could change under the influence of other topics (Goren & Chapp 2017). In such a situation, it should examine whether oil spill polarization based on political identity occurs.

Additionally, this study simulates two types of preferences: static preferences that are fixed and dynamic preferences that frequently change through interactions. However, real-world topics also include “quasi-static topics” that fall between these categories – preferences that do not change as easily as dynamic topics but are not as fixed as static preferences (Baldassarri & Gelman 2008). These hot-button topics are linked to political identity, making it essential to consider their correlation.

Finally, we mention partisanship. This study focuses on two opposing identities as represented by a two-party political system like that of the US. However, polarization is also a concern in regions with multiparty systems; study under such conditions will be necessary. Research on oil spill polarization in these regions is limited. Therefore, when extending this study to a multiparty system requires combining empirical studies and simulations to better understand the current situation and mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 23K04284, JP23K20588 and by The Fujikura Foundation and by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2124.Model Documentation

The model was built in NetLogo 6.3. The model code can be found at: https://www.comses.net/codebases/fe2381dc-91a6-4407-a97b-8c04a2d2341f/releases/1.0.0/References

BAKSHY, E., Messing, S., & Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science, 348(6239), 1130–1132. [doi:10.1126/science.aaa1160]

BALDASSARRI, D., & Gelman, A. (2008). Partisans without constraint: Political polarization and trends in American public opinion. American Journal of Sociology, 114(2), 408–446. [doi:10.1086/590649]

BEDNAR, J. (2021). Polarization, diversity, and democratic robustness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(50), e2113843118. [doi:10.1073/pnas.2113843118]

BESSI, A., Petroni, F., Del Vicario, M., Zollo, F., Anagnostopoulos, A., Scala, A., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2015). Viral misinformation: The role of homophily and polarization. roceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web. [doi:10.1145/2740908.2745939]

BLEAKLEY, P. (2023). Panic, pizza and mainstreaming the alt-right: A social media analysis of pizzagate and the rise of the QAnon conspiracy. Current Sociology, 71(3), 509–525. [doi:10.1177/00113921211034896]

BOURDIEU, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1990). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

BRIGHT, J. (2018). Explaining the emergence of political fragmentation on social media: The role of ideology and extremism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(1), 17–33. [doi:10.1093/jcmc/zmx002]

CINELLI, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., & Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9), e2023301118. [doi:10.1073/pnas.2023301118]

CONOVER, M. D., Gonçalves, B., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2012). Partisan asymmetries in online political activity. EPJ Data Science, 1(1), 1–9. [doi:10.1140/epjds6]

CONWAY, P. R. (2021). Radicalism, respectability, and the colour line of critical thought: An interdisciplinary history of critical international relations. Millennium, 49(2), 337–367. [doi:10.1177/03058298211031293]

DELLAPOSTA, D. (2020). Pluralistic collapse: The “oil spill” model of mass opinion polarization. American Sociological Review, 85(3), 507–536. [doi:10.1177/0003122420922989]

DELLAPOSTA, D., Shi, Y., & Macy, M. (2015). Why do liberals drink lattes? American Journal of Sociology, 120(5), 1473–1511. [doi:10.1086/681254]

DEL Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Scala, A., Petroni, F., Caldarelli, G., Stanley, H. E., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554–559. [doi:10.1073/pnas.1517441113]

DIAZ Ruiz, C., & Nilsson, T. (2023). Disinformation and echo chambers: How disinformation circulates on social media through identity-driven controversies. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 42(1), 18–35. [doi:10.1177/07439156221103852]

ESSIG, L., & DellaPosta, D. (2024). Partisan styles of self-presentation in U.S. Twitter bios. Scientific Reports, 14, 1077. [doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50810-0]

GENTZKOW, M. (2016). Polarization in 2016. Available at: https://web.stanford.edu/~gentzkow/research/PolarizationIn2016.pdf

GOREN, P. (2005). Party identification and core political values. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 881–896. [doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00161.x]

GOREN, P., & Chapp, C. (2017). Moral power: How public opinion on culture war issues shapes partisan predispositions and religious orientations. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 110–128. [doi:10.1017/s0003055416000435]

GUESS, A., Nyhan, B., Lyons, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Avoiding the echo chamber about echo chambers: Why selective exposure to like-minded political news is less prevalent than you think. Knight Foundation.

HEIDER, F. (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

HITKUL, P. A., Guhathakurta, D., Jain, J., Subramanian, M., Reddy, M., Sehgal, S., Karandikar, T., Gulati, A., Arora, U., Shah, R. R., & Kumaraguru, P. (2021). Capitol (Pat)riots: A comparative study of Twitter and Parler. arXiv:2101.06914

HUNTER, J. D. (1991). Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. New York, NY: Basic Books.

JENKE, L. (2024). Affective polarization and misinformation belief. Political Behavior, 46(2), 825–884. [doi:10.1007/s11109-022-09851-w]

KHANAM, K. Z., Srivastava, G., & Mago, V. (2023). The homophily principle in social network analysis: A survey. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 82(6), 8811–8854. [doi:10.1007/s11042-021-11857-1]

KILEY, K., & Vaisey, S. (2020). Measuring stability and change in personal culture using panel data. American Sociological Review, 85(3), 477–506. [doi:10.1177/0003122420921538]

KLAPPER, J. T. (1960). The Effects of Mass Communication. Boston, MA: Free Press.

KOBELLARZ, J. K., Brocic, M., Silver, D., & Silva, T. H. (2024). Bubble reachers and uncivil discourse in polarized online public sphere. PLos One, 19(6), e0304564. [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0304564]

KOGAN, L. R., McDonald, S. E., & Swan, L. E. (2024). “Childless cat ladies” and the 2024 US presidential election. Human-Animal Interactions, 12(1). [doi:10.1079/hai.2024.0036]

KUBIN, E., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(3), 188–206. [doi:10.1080/23808985.2021.1976070]

KWAK, H., Chun, H., & Moon, S. (2011). Fragile online relationship: A first look at unfollow dynamics in Twitter. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. [doi:10.1145/1978942.1979104]

LELKES, Y. (2018). Affective polarization and ideological sorting: A reciprocal, albeit weak, relationship. The Forum, 16(1), 67–79. [doi:10.1515/for-2018-0005]

LUTTIG, M. D. (2018). The “prejudiced personality” and the origins of partisan strength, affective polarization, and partisan sorting. Political Psychology, 39, 239–256. [doi:10.1111/pops.12484]

MCPHERSON, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. [doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415]

PERALTA, A. F., Ramaciotti, P., Kertész, J., & Iñiguez, G. (2024). Multidimensional political polarization in online social networks. Physical Review Research, 6(3). [doi:10.1103/physrevresearch.6.013170]

PRAET, S., Guess, A. M., Tucker, J. A., Bonneau, R., & Nagler, J. (2021). What’s not to like? Facebook page likes reveal limited polarization in lifestyle preferences. Political Communication, 39(3), 311–338. [doi:10.1080/10584609.2021.1994066]

RAWLINGS, C. M., & Childress, C. (2024). The polarization of popular culture: Tracing the size, shape, and depth of the “oil spill”. Social Forces, 102, 1582–1607. [doi:10.1093/sf/soad150]

ROSS Arguedas, A., Robertson, C., Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2022). Echo chambers, filter bubbles, and polarisation: A literature review. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

SHOOK, N. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2009). Political ideology, exploration of novel stimuli, and attitude formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 995–998. [doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.003]

SIBONA, C., & Walczak, S. (2011). Unfriending on Facebook: Friend request and online/offline behavior analysis. Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. [doi:10.1109/hicss.2011.467]

SUNSTEIN, C. R. (2007). Ideological amplification. Constellations, 14(2), 273–279. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-8675.2007.00439.x]

TAKIKAWA, H., & Nagayoshi, K. (2017). Political polarization in social media: Analysis of the Twitter political field in Japan. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data. [doi:10.1109/bigdata.2017.8258291]

TALAIFAR, S., Jordan, D., Gosling, S. D., & Harari, G. M. (2025). Lifestyle polarization on a college campus: Do liberals and conservatives behave differently in everyday life? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 129(1), 152–180. [doi:10.1037/pspp0000545]

TERREN, L., & Borge, R. (2021). Echo chambers on social media: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Communication Research, 9, 99–118.

TÖRNBERG, P. (2022). How digital media drive affective polarization through partisan sorting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(42).

VAN Zoonen, L. (2013). From identity to identification: Fixating the fragmented self. Media, Culture & Society, 35(1), 44–51. [doi:10.1177/0163443712464557]

WESTHEUSER, L., & Zollinger, D. (2025). Cleavage theory meets Bourdieu: Studying the role of group identities in cleavage formation. European Political Science Review, 17(1), 110–127. [doi:10.1017/s1755773924000249]

WOJCIESZAK, M., & Warner, B. R. (2020). Can interparty contact reduce affective polarization? A systematic test of different forms of intergroup contact. Political Communication, 37(6), 789–811. [doi:10.1080/10584609.2020.1760406]