GPLab: A Generative Agent-Based Framework for Policy Simulation and Evaluation

,

and

aSchool of Law, Zhengzhou University, China; bFintech Thrust, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou), China; cFaculty of Engineering, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 29 (1) 6

<https://www.jasss.org/29/1/6.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5933

Received: 05-Jul-2025 Accepted: 16-Jan-2026 Published: 31-Jan-2026

Abstract

Real-world social policy problems invariably involve complex dynamics with cross-domain, multi-factor interactions, posing significant challenges to ex-ante policy simulation and impact evaluation. Traditional statistical modeling approaches often fail to adequately capture individual behavioral heterogeneity and system-level dynamic propagation effects, while conventional agent-based modeling (ABM) relies heavily on hand-crafted behavioral rules, which constrains its adaptability to realistic decision-making processes and diverse policy contexts. To address this challenge, we propose GPLab (Generative Policy Laboratory), a general-purpose framework for policy simulation and evaluation that integrates generative Large Language Models (LLMs). By leveraging LLM-based agents with bounded rationality, GPLab simulates the cognition and behavior of social individuals, overcoming critical limitations of rule-based ABM in policy semantic understanding and scenario adaptation. Furthermore, its modular architecture explicitly represents interconnected social subsystems, enabling heterogeneous agents to interact dynamically across multiple domains and produce contextually grounded behavioral responses. In two representative policy evaluation cases, we successfully captured policy intensity-dependent effects, group behavioral heterogeneity, and emotional opinion evolution patterns. Formal consistency metrics further confirmed the stability of agent behavior and coherence of individual traits throughout simulations. Extended experiments demonstrated that our framework achieved high rationality scores across five policy scenarios, validating its cross-domain transferability. This study presents a scenario-agnostic policy simulation platform that significantly advances computational social science applications in public decision support. The code is available at: https://github.com/SmartLegislation/GPLabIntroduction

Effective policy evaluation is crucial for understanding policy effectiveness and optimizing government decision-making. Traditional ex-post approaches, such as difference-in-differences and instrumental variable methods, have made substantial contributions to causal inference under relatively static settings, yet they often fall short in capturing individual-level behavioral heterogeneity and system-level dynamic transmission effects (Angrist & Pischke 2009; Guangyi Wang et al. 2024). In contrast, agent-based modeling (ABM) offers a bottom-up paradigm that simulates interactions among policy participants and generates emergent macro outcomes (Lempert 2002; Tisue & Wilensky 2004). However, many ABM implementations rely on simplified behavioral rules or stylized utility functions, which limits their ability to reflect realistic decision processes and reduces their applicability across diverse policy contexts (Nespeca et al. 2023).

In recent years, rapid advancements in large language models (LLMs) have enabled these AI systems, trained on massive text corpora, to demonstrate flexible text generation and natural language interaction capabilities. Therefore, existing studies have attempted to embed LLMs within intelligent agents to construct a generative agent-based modeling (GABM) (Ghaffarzadegan et al. 2024) framework to enhance the cognition and decision-making realism of agents in virtual societies. Although existing frameworks have introduced LLM-based agents for complex social simulation, they frequently focus on building large-scale, unified sociological models, or are limited to fixed social subsystems (Piao et al. 2025). Such models are often resource-intensive and analytically diffuse, and offer limited precision for domain-specific policy questions. As a result, they lack the adaptability for diverse policy applications and do not fully leverage social behavior theories to simulate bounded rational behavioral response mechanisms of individuals under policy influences. In contrast, effective policy simulation requires targeted, high-resolution modeling within a constrained scope rather than an all-encompassing systemic replica.

To bridge this gap, we introduce GPLab (Generative Policy Laboratory) – a general framework for social policy simulation and evaluation. The framework consists of three core modules: 1) The Social Agent Module employs LLM-based agents to simulate individual behaviors, and through the integration of bounded rationality theory (Jones 2002), designs dynamic cognitive mechanisms that enable agents to exhibit both rational and non-rational real-world decision-making characteristics. 2) The Social Subsystem Module adopts a modular and composable architecture, enabling the flexible configuration of diverse policy scenarios and facilitating cross-system interactions among agents. 3) The Simulation and Evaluation Module leverages a simulation engine for high-throughput concurrent simulations and utilizes a multi-dimensional evaluator to comprehensively quantify policy impacts both within and across subsystems. Collectively, the entire framework can effectively simulate the transmission process and implementation effects of policies in cross-domain social networks, significantly enhancing the flexibility, universality, and evaluation effectiveness of policy simulation. Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

- We introduce GPLab, a novel framework that pioneers the integration of LLM-based agents with modular social subsystem architecture to simulate dynamic cross-domain policy transmission and implementation effects.

- We incorporate bounded rationality theory into LLM-based social agents through dynamic cognitive modules that combine memory retrieval and emotional processing, enabling realistic simulation of both rational and non-rational human decision-making patterns.

- We develop a modular and composable social subsystem architecture grounded in social system theory, providing flexible infrastructure for customized policy scenario modeling and cross-domain application.

- We comprehensively validate GPLab’s effectiveness through two detailed case studies leveraging Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) data, and demonstrate the framework’s broad applicability and transferability via extensive experiments across five distinct policy evaluation domains.

The experimental results demonstrated that GPLab successfully identified policy intensity-dependent effects, group behavioral heterogeneity, and emotional opinion evolution patterns in consumption voucher and new energy vehicle promotion policies. The stability of agent behavior and trait consistency was also verified through formal consistency metrics. Moreover, in extended experiments across five different policy domains, the model consistently achieved high rationality scores, demonstrating excellent cross-scenario applicability and transferability. As computational resources and data acquisition capabilities continue to advance, GPLab is poised to serve as a universal policy simulation platform for complex social policy evaluation, playing an increasingly vital role in policy research and public decision support.

Related Work

ABM methods in policy simulation and evaluation

Policy simulation and evaluation constitutes a systematic assessment of how policies or public programs achieve their intended objectives, focusing on identifying both successes and obstacles in goal attainment (Mark et al. 2009). Contemporary policy evaluation methods, including questionnaire surveys, statistical regression, and econometric models, primarily rely on macro-level statistical correlations (Athey & Imbens 2017). However, these approaches typically assume population homogeneity and behavioral independence, limiting their ability to capture heterogeneous individual interactions and complex system dynamics during policy implementation.

To address these limitations, ABM simulates interactions among individuals and between individuals and their environment through autonomous behavioral rules, enabling macro-level social effects to emerge from micro-level interactions. Recent applications demonstrate ABM’s effectiveness in evaluating policy implementation across environmental (von Essen & Lambin 2023; Z. Zhang & Han 2024), agricultural (Kremmydas et al. 2018; Marvuglia et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2021), and economic (Gamal et al. 2024; Jia & McNamara 2024; Steinbacher et al. 2021) domains, introducing microscopic heterogeneous behavior and complex system perspectives to policy evaluation while providing foundations for more realistic experimental environments (Tisue & Wilensky 2004). However, existing policy simulation frameworks face certain limitations. NetLogo is a general-purpose modeling language that relies on explicit rule-based programming, but currently lacks mature modules, algorithms, or extensions that can support semantic policy content or bounded rationality approximating complex human behavior. Health-GPS focuses on health policy but lacks cross-domain adaptability. Large-scale assessment platforms like C3IAM (Wei 2025) employ complex modeling but are resource-intensive and inflexible for diverse policy scenarios. Nevertheless, ABM modeling typically relies on predefined behavioral rules and expert knowledge, constraining adaptability to open environments and limiting behavioral authenticity and generalization in complex social contexts. Enhancing reliability and usability (D’Auria et al. 2020) remains a critical challenge in policy simulation and computational social science.

Large language model-based agents

Recent years have witnessed remarkable progress in LLM development within artificial intelligence. Pre-trained models such as BERT and GPT series (Devlin et al. 2019; Floridi & Chiriatti 2020), trained on extensive corpora, exhibit exceptional language understanding and generation capabilities. OpenAI’s GPT-4 achieves substantial improvements in parameter scale and comprehension, surpassing human performance across multiple domains (Achiam et al. 2023). The open-source community has contributed models with enhanced reasoning capabilities, notably DeepSeek-R1, which advances chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning, a technique that guides models to solve complex problems through intermediate reasoning steps and complex problem-solving through reinforcement learning (Guo et al. 2025).

These developments have catalyzed the emergence of LLM-based Agents (L. Wang et al. 2024), which leverage LLMs as cognitive cores through sophisticated prompt design and organizational architectures (Yao et al. 2023), enabling environmental perception, action planning, and interactive capabilities. For instance, Voyager integrates GPT-4 into interactive environments like Minecraft, enabling continuous skill acquisition through trial and error, pioneering unsupervised open-ended lifelong learning agents (Wang et al. 2023). Multi-agent planning and cooperation further amplify system capabilities. AgentVerse provides collaborative environment construction tools that support dynamic agent addition and adjustment for group behavior simulation (Chen et al. 2023). The CAMEL framework investigates communication and collaboration among LLM-based multi-agents to explore societal collaborative challenges (Li et al. 2023). MetaGPT adopts software engineering principles, assigning LLM-based Agents to diverse roles including product managers and engineers for collaborative task completion, substantially improving multi-agent system reliability in real-world problem-solving (Hong et al. 2023). These advances signal LLM-based Agent technology’s evolution from language tasks to complex system modeling, with anthropomorphic reasoning, role collaboration, and environmental interaction capabilities establishing foundations for next-generation multi-agent social simulation platforms (Park et al. 2022), opening new possibilities for human behavior prediction and policy simulation applications.

GABM-based social simulation

Building on traditional ABM, researchers have developed GABM, a more versatile and cognitively sophisticated simulation paradigm (Ghaffarzadegan et al. 2024).

In ABM contexts, LLMs function as cognitive cores by processing structured prompts containing agent characteristics and environmental information, generating contextually appropriate behavioral decisions through semantic reasoning rather than discrete rule-based logic, enabling authentic policy response simulation that traditional ABM approaches cannot achieve (Aher et al. 2023).

Unlike traditional ABM’s reliance on predefined interaction rules, GABM empowers agents with powerful LLMs, endowing them with language understanding, situational perception, and autonomous decision-making capabilities, thereby achieving more authentic and dynamic individual simulation.

Park et al.’s seminal Generative Agents system (Park et al. 2023) embedded 25 LLM-based Agents with human cognitive structures into virtual social environments, demonstrating the spontaneous emergence of human-like social patterns and group behaviors. GABM-based social simulation has found extensive applications across economics (Hao & Xie 2025; Li et al. 2024), social networks and communication (Chuang et al. 2024; Liu et al. 2024; Mou et al. 2024), public administration (Xiao et al. 2023), political elections (Li et al. 2025; X. Zhang et al. 2024), and public health (Williams et al. 2023). These cross-domain applications demonstrate that GABM represents a novel computational sociology paradigm where agents possess not only interactive capabilities but also strategic adaptation abilities in complex situations.

Nevertheless, existing GABM simulation frameworks that can be applied to policy simulation tend to focus on building large-scale, unified models, which often lack the precision necessary for addressing domain-specific policy questions (Piao et al. 2025). This highlights the need for a specialized GABM framework designed for policy simulation and evaluation, one that can capture both individual behavioral authenticity and cross-domain policy transmission effects.

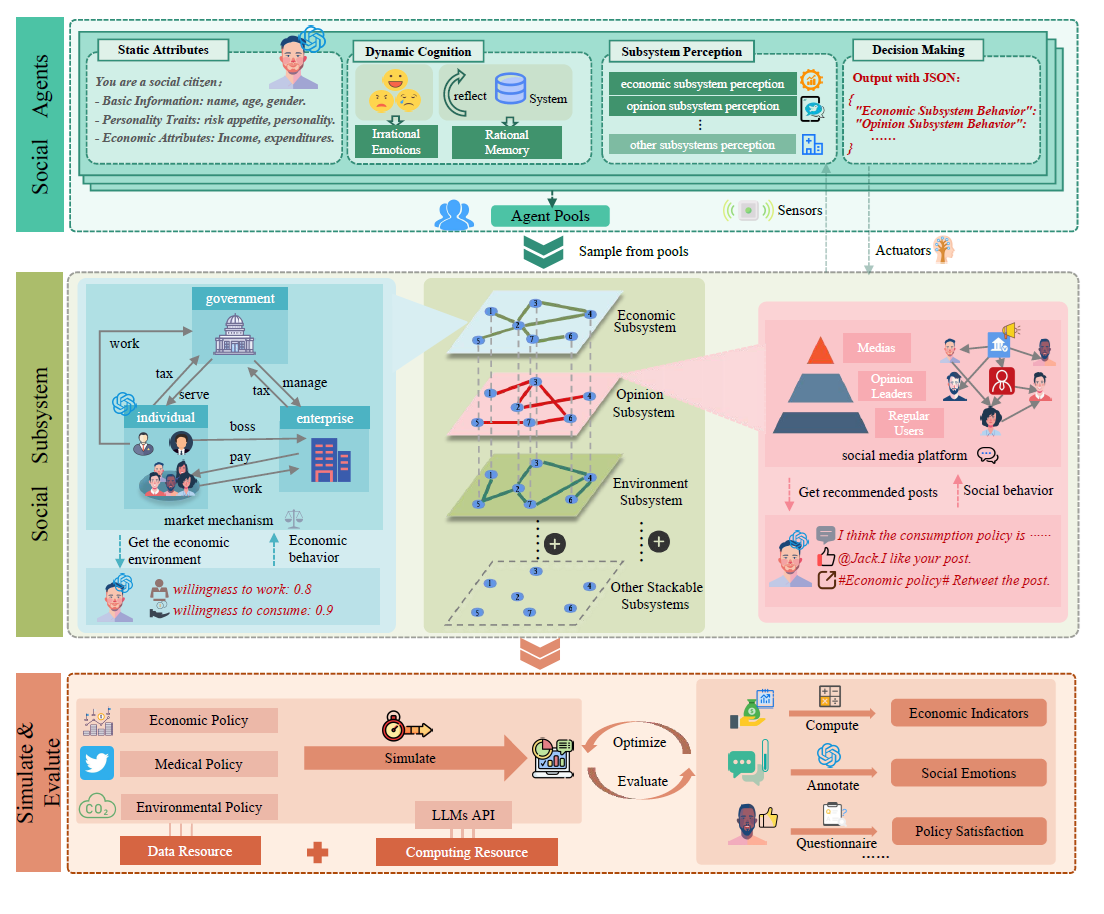

GPLab Framework

GPLab represents a fundamentally LLM-driven policy simulation framework that integrates generative AI capabilities with modular social system architecture to overcome traditional ABM limitations. GPLab adopts a three-layer architecture, as illustrated in Figure 1, comprising Social Agents, Social Subsystem, and Simulate & Evaluate layers. The Social Agents layer undamentally relies on LLMs to drive individual behavior simulation through four integrated modules: static attributes, dynamic cognition, subsystem perception, and decision-making. LLMs enable agents to process complex policy information, integrate personal characteristics with environmental context, and generate contextually appropriate behavioral responses. The dynamic cognition module combines non-rational emotional mechanisms with rational memory systems to authentically represent decision-making complexity. The Social Subsystem layer employs modular design principles, seamlessly integrating subsystems from economics, public opinion, and environmental domains to simulate policy transmission across social hierarchies. LLM-driven agents serve as the intelligent interfaces that process and respond to cross-subsystem information flows The Simulate & Evaluate layer establishes a closed-loop evaluation system through data-driven computational optimization, enabling quantitative policy effect analysis and iterative refinement, thus ensuring simulation effectiveness and practical applicability.

To ensure robust engineering implementation, GPLab integrates established theoretical foundations from social science as design guidelines. Social systems inherently exhibit structural order and behavioral patterns, which GPLab operationalizes through three key sociological models. The interaction model integrates micro-level agent interactions, semantic perception, cross-subsystem coupling, and temporal feedback to capture dynamic, context-sensitive social processes (Bales 1950). This guides the design of the agent layer, where decisions are shaped by situational awareness and symbolic communication. The system model, focusing on societal structure and subsystem linkages (Schirmer & Michailakis 2018), informs GPLab’s modular architecture, facilitating cross-domain feedback and emergent behaviors in simulations. Finally, the conflict model examines group interest dynamics and class interactions (Amblard et al. 2010), guiding the simulation evaluation layer to assess the differential impacts of policy across diverse groups. These established theoretical models serve as engineering guidelines for GPLab’s implementation, enabling the capture of complex, interdependent social processes.

Social agent module

The Social Agent Module constitutes the foundational layer of our framework, wherein individual agents are modeled as autonomous heterogeneous entities that exhibit adaptive behaviors within simulated social environments. These agents are grounded in Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen 1991), where decision-making processes are structured through attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, providing a scientific foundation for modeling individual behavioral intentions and choices. Each agent operates according to personalized objectives and responds to environmental stimuli through sophisticated cognitive mechanisms. The policy transmission process is formalized as an information flow from social subsystems to individual agents, which subsequently generate behavioral responses through their integrated cognitive models. These behavioral outputs are then propagated back to the corresponding subsystems, establishing a bidirectional feedback loop. The concurrent interactions among subsystems create a complex network of information exchange, thereby generating the emergent dynamics that characterize agent-environment interactions.

The framework design aims to achieve authentic simulation of these social processes, making the modeling design of heterogeneous social individuals particularly crucial. To embed LLMs into each agent’s unique “digital brain”-like cognitive architecture, we employ prompt engineering techniques to construct a unified prompt template framework. By injecting personalized role-specific information into the template, the foundation LLMs can generate reliable decisions that reflect individual characteristics. Specifically, the prompt input for each social agent consists of four core modules:

- Static Attribute Module: Each heterogeneous social agent possesses unique social identity characteristics. We employ extensible configuration files to define basic information, psychological attributes, social attributes, and economic attributes as foundational role categories. LLMs can further generate enriched character profiles from existing information, creating comprehensive life archives for virtual characters.

- Dynamic Cognition Module: Herbert A. Simon’s bounded rationality (Jones 2002) posits that humans cannot perform comprehensive cost-benefit analyses due to cognitive, temporal, and informational constraints, instead making decisions through “satisficing rather than optimizing”. Drawing on this insight, our dynamic cognition module integrates emotion systems governing non-rational decision factors with memory systems managing rational decision elements, forming the modular foundation for social agents’ dynamic cognition.

- Memory System: Aligned with human cognitive processes (Squire & Wixted 2011), the memory system employs Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technology (Lewis et al. 2020) to construct long-term memory repositories, continuously accumulating experiential data from individual experiences. Each memory entry carries timestamps and temporal weighting. During decision-making, agents retrieve contextually relevant memories and periodically generate reflective insights to enrich their memory repositories.

- Memory Retrieval Strategy: To model human memory’s temporal characteristics, we implement a time-weighted nearest neighbor retrieval mechanism that assigns weights to each memory:

where \(w\) denotes the comprehensive weight of the current memory entry, \(\Delta t\) represents the time difference between the memory and current time, \(\mathrm{sim}\) indicates the semantic similarity between the current situation and the memory, and \(\lambda \in [0,1]\) serves as a strategy control parameter that determines the relative emphasis between recency-based and relevance-based memory retrieval, where the weighted combination ensures that both temporal and semantic factors contribute to memory activation in an adaptive, context-dependent manner. This mechanism effectively modulates the activation probability of older memories while enhancing retrieval quality for task-relevant information, thereby strengthening agents’ response consistency and cognitive stability in complex situations.\[w = \lambda \cdot e^{-\Delta t} + (1 - \lambda) \cdot \mathrm{sim}\] \[(1)\] - Memory Reflection Strategy: When sufficient new memories accumulate, the system initiates a reflection process. This process leverages LLMs’ semantic understanding to generate high-level reflective insights from recent historical memories, storing these abstractions in long-term memory to enhance memory integration and conceptual understanding. The specific prompt template for memory reflection is detailed in Appendix C.

- Memory Retrieval Strategy: To model human memory’s temporal characteristics, we implement a time-weighted nearest neighbor retrieval mechanism that assigns weights to each memory:

- Emotion System: Real individuals frequently exhibit non-rational influences in behavioral decisions, which we model through agents’ emotion systems. LLMs can effectively capture and simulate human emotions, providing strong empirical support for our approach (Ishikawa & Yoshino 2025). During each interaction, we employ LLMs to extract current emotional states from historical memory containing external environmental perceptions and internal cognitive processes, following the cognitive evaluation framework where emotions emerge from the assessment of environmental stimuli relative to personal goals and past experiences (Ortony et al. 2022), integrating these dynamic emotions into the cognitive module to influence subsequent behavioral decisions. The emotion extraction prompt template is provided in Appendix D.

- Memory System: Aligned with human cognitive processes (Squire & Wixted 2011), the memory system employs Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technology (Lewis et al. 2020) to construct long-term memory repositories, continuously accumulating experiential data from individual experiences. Each memory entry carries timestamps and temporal weighting. During decision-making, agents retrieve contextually relevant memories and periodically generate reflective insights to enrich their memory repositories.

- Subsystem Perception Module: In real societies, individuals access environmental information through diverse channels, with social media serving as an increasingly important pathway for understanding policy content and social evaluations, particularly among digitally connected populations, which shapes cognitive decisions. Our design enables social agents to acquire environmental state information (including economic policies, conditions, and social media content) through subsystem interfaces. At each time step \(t\), social agent \(i\) aggregates information from multiple social subsystems, forming current environmental perception \(E_i^t\) in textual form:

where \(s_{j,i}^t\) represents the information perceived by agent \(i\) from the \(j\)-th social subsystem at time step \(t\), and \(m\) denotes the total number of subsystems. This process simulates how social individuals perceive information from various social environments.\[E_i^t = \{ s_{1,i}^t, s_{2,i}^t, \ldots, s_{m,i}^t \}\] \[(2)\] - Behavioral Decision Module: Upon acquiring environmental information from subsystems, the behavioral decision module guides agents in formulating appropriate responses to each subsystem. The module enforces standard JSON output format with decision rationales, which improves structured data extraction and facilitates systematic analysis of agent responses while enhancing interpretability. We employ LLMs as decision cores, constructing prompts via predefined templates for LLM processing, then parsing outputs to drive agent behaviors:

where \(d_i^t\) represents the behavioral decision output of agent \(i\) at time \(t\), \(a_i\) denotes the agent’s static attribute information, \(m_i^t\) and \(e_i^t\) represent the current dynamic cognitive state (including memory and emotion respectively), \(E_i^t\) indicates the environmental information obtained from the subsystem perception module, and \(c\) denotes the action normalizer. This process is uniformly driven through the ReAct prompting paradigm (Yao et al. 2023). A detailed example of the agent behavioral decision prompt template is provided in Appendix B, and the complete algorithmic process is outlined in Appendix E.\[d_i^t = \mathrm{LLM}(a_i, m_i^t, e_i^t, E_i^t, c)\] \[(3)\]

Social subsystem module

Modern society consists of multiple interconnected subsystems, each serving specific functions to maintain social stability and order (Parsons 2013). Building on this understanding, we divide the agent interaction environment into functionally distinct units when simulating policy transmission processes. Each unit has clear boundaries, independent operations, and well-defined interfaces, which improves the precision and flexibility of policy evaluation. Different policy types affect different social subsystems: consumption voucher policies mainly influence economic behavior subsystems, healthcare policies impact medical subsystems, and information regulations affect public opinion transmission subsystems. To meet diverse policy evaluation needs, we propose a modular social subsystem architecture that allows researchers to design and integrate subsystems tailored to specific policy contexts. Each subsystem maintains independent operational mechanisms and performance indicators.

Each social subsystem is modeled as an independently operating modular unit with the following two key characteristics:

- Decoupled Design. Through subsystem separation, researchers can independently develop subsystem designs before simulation without rebuilding the entire system. Our shared message board mechanism enables communication between subsystems through read/write operations, making information exchange easier. Each subsystem maintains operational independence during simulation under unified scheduler management. After simulation, subsystem indicators support flexible evaluation and analysis.

- Interventional Design. Social subsystems support flexible intervention capabilities. Policy content exists within subsystems as text or parameters, with triggering mechanisms following predetermined designs. This architecture enables straightforward policy experimentation and comprehensive social analysis.

For example, when simulating consumption stimulus policies, an “Economic Behavior Subsystem” can be designed with internal mechanisms including income models, consumption willingness models, and price feedback mechanisms for social agents as consumers (Tsiatsios et al. 2024). When simulating public event response policies, a “Public Opinion Transmission Subsystem” can be introduced, including opinion diffusion networks with “virtual netizens” participation and platform recommendation logic (Yao et al. 2025).

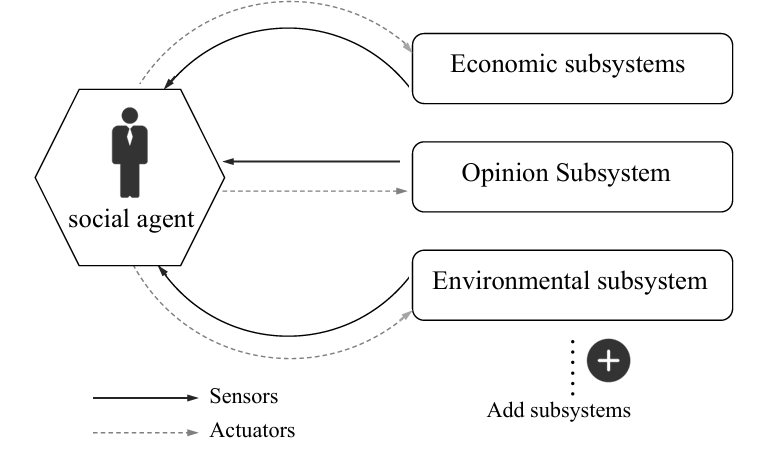

Agent-subsystem interaction mechanism

Following interaction theory (Bales 1950), social structures emerge from continuous micro-level interactions rather than fixed arrangements. This framework establishes dynamic interaction patterns among agents, between agents and subsystems, and across subsystems, driving social system integration and development. Individuals understand their environment through shared meanings, making decisions based on how they interpret situations, with social rules forming through repeated interactions.

Our social agents take on different roles within social systems, performing various functions across subsystems while acting as channels for policy transmission across multiple social levels. During interactions, agents use subsystem perception modules to gather information from each subsystem. This information influences their behavioral choices, which then affect various social subsystems, thus changing how subsystems operate, as shown in Figure 2. This perception-feedback structure captures both individual behavioral interactions within subsystems and policy effects across multiple social levels through agent-centered processes.

Therefore, for each social subsystem \(s_j\), its state evolution depends on its previous state \(s_j^{t-1}\) and the set of all social agent behaviors at that time step \(\{d_1^t, d_2^t, \ldots, d_n^t\}\). The formula is as follows:

| \[s_j^t = f_j(s_j^{t-1}, \{ d_1^t, d_2^t, \ldots, d_n^t \})\] | \[(4)\] |

Simulation and evaluation module

GPLab provides researchers with flexible configuration options to adapt simulations to different policy contexts. The framework allows customization of key parameters including language model API services, social agent characteristics, subsystem operations, and simulation engine settings. These configuration options enable tailored simulation scenarios across different policy types, implementation scales, and social environments. Agent profile information captures individual characteristics that serve as direct targets for policy evaluation. Researchers can easily load population data through standard JSON formats. Policy content, as a core subsystem parameter, can be configured in detail before simulation begins.

Based on the interactive framework of social agents and subsystems, we develop a simulation control engine that manages dynamic policy transmission and feedback processes over time and space:

- For time management, the simulation engine maps real-world time periods to simulation steps, allowing researchers to set simulation start and end points, time intervals, and policy implementation timing to match actual policy lifecycles.

- For coordination across subsystems, the simulation engine manages multiple social subsystems simultaneously while monitoring their states. Social agent decisions are powered by multiple language model APIs running in parallel, and we use load balancing techniques to optimize API usage efficiently. This design increases the richness and adaptability of agent behaviors while maintaining fast system performance for large-scale simulations.

After simulation completion, the system conducts thorough evaluation of both individual behaviors and system-wide outcomes, employing language models to perform intelligent analysis through two mechanisms: automated processing of simulation time-series data to identify behavioral patterns, policy transmission effects, and anomalies across agent populations and subsystems, generating natural language summaries of key performance indicators such as consumption trends, heterogeneity patterns, and cross-subsystem interactions; and structured credibility assessment where models evaluate simulation authenticity across dimensions including behavioral realism, causal consistency, and temporal dynamics, producing both quantitative scores and qualitative explanations. Evaluation measures are designed to match specific scenarios. Based on evaluation results, researchers can adjust policy parameters and run new experiments, creating an ongoing cycle of “evaluation-improvement-re-evaluation” for policy optimization.

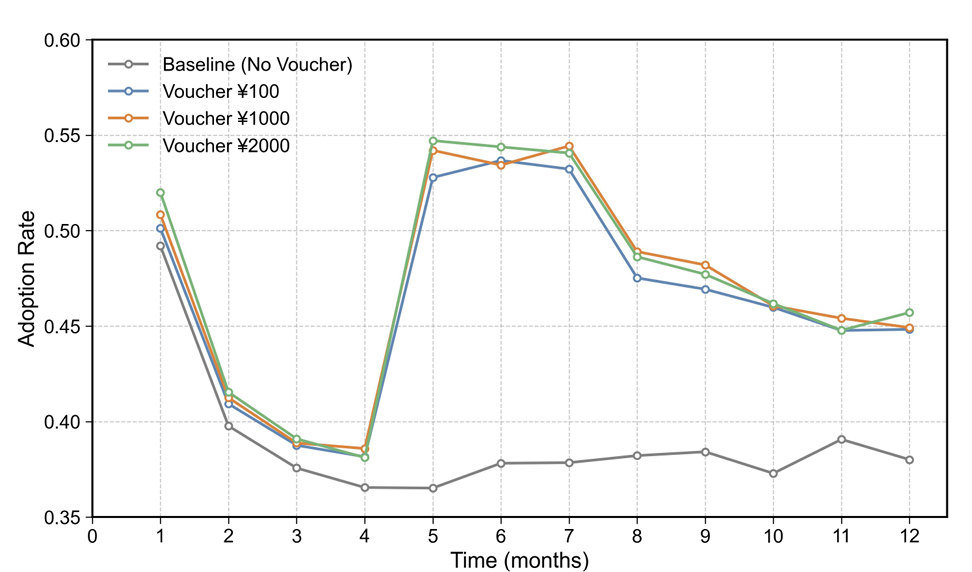

We demonstrate GPLab’s effectiveness in complex social dynamics through a representative policy study of government economic stimulus measures. Specifically, we analyze how consumption voucher distribution during public health emergencies impacts social economic behavior and public sentiment. The simulation spans 12 time steps at monthly intervals (months 0-11), with months 4-6 designated for voucher policy announcement and implementation, as shown in Table 1.

| Month | Economic Behavior Subsystem Policy | Social Opinion Subsystem News |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | / | Seasonal flu outbreak in a city, current prevention situation is urgent! |

| 1 | / | Emergency notice! Tense situation, multiple regions across the country activate major public health emergency response to address sudden infection events |

| 2 | / | Warning! Public gathering epidemic comes fiercely, please take protective measures, reduce going out, avoid gatherings |

| 3 | / | Epidemic continues to escalate, situation remains concerning, everyone needs to stay vigilant! |

| 4 | To promote consumption and stimulate the economy, the government has decided to issue consumption vouchers worth 100/1000/2000 yuan per person, which can be used for various types of consumption | Currently in a special period of epidemic prevention and control, please take protective measures, reduce going out, avoid gatherings |

| 5 | The consumption voucher policy continues to be implemented, with the second batch of vouchers issued at 100/1000/2000 yuan per person, encouraging consumers to increase spending | Currently in a special period of epidemic prevention and control, please take protective measures, reduce going out, avoid gatherings |

| 6 | The consumption voucher policy enters its final month, with regions continuing to issue vouchers and urging the public to use them quickly | Currently in a special period of epidemic prevention and control, please take protective measures, reduce going out, avoid gatherings |

| 7–10 | / | … |

| 11 | / | Currently in a special period of epidemic prevention and control, please take protective measures, reduce going out, avoid gatherings |

Social agent initialization

To ensure realistic consumption behavior modeling, we construct initial population samples from Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS 2018) data1. We employ LLMs to extract and enrich personal attributes from raw data, process these into JSON format, and randomly sample 500 individuals as social agents. Social agents are driven by the open-source LLM glm-4-9b model2. In each month’s simulation, agents make the following behavioral responses based on perceived social subsystem information (Li et al. 2024):

- Consumption willingness: a number between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating willingness to consume;

- Savings preference: a number between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating willingness to save;

- Work willingness: a number between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating willingness to work;

- Social behavior: posting, reposting seen posts, or liking seen posts;

Social subsystem design

Economic Behavior Subsystem. This subsystem delivers economic policy information and current social conditions to agents while collecting their behavioral responses to calculate overall economic indicators. We implement the consumption voucher policy during months 4-6, following the timeline shown in Table 1.

Social Opinion Subsystem. This subsystem provides news updates and peer opinions to agents while enabling social interactions between them. To help agents understand the changing epidemic situation, we send monthly news updates to all agents, modeling real-world news feed systems as described in Table 1.

Experimental Results

Changes in Consumption Willingness under Different Voucher Amounts. Figure 3 illustrates consumption willingness dynamics across varying voucher denominations. Results revealed consumption voucher policies’ immediate impact and intensity-dependent characteristics, while highlighting phased policy effects. Pre-implementation (months 0-3), consumption willingness universally declined, likely reflecting public health events’ economic suppression. Policy intervention (months 4-6) dramatically altered consumption trajectories. All voucher denominations triggered immediate consumption willingness rebounds in month 4. Predictably, larger vouchers yielded greater improvements, with the 2000 yuan group achieving peak willingness of 0.55, substantially exceeding the 100 yuan (0.53) and 1000 yuan (0.54) groups. This demonstrates positive correlation between incentive intensity and effect magnitude during early implementation. Post-policy (months 7-11), consumption willingness declined across all voucher groups yet remained elevated relative to control groups. Notably, late-stage differences between voucher denominations converged, suggesting that while high-value vouchers provide stronger immediate stimulus, long-term effects involve more complex moderating factors.

During implementation, despite higher initial gains from larger vouchers, all groups exhibited fluctuations and convergence patterns. This likely reflects consumers’ immediate concentrated spending upon subsidy receipt followed by behavioral normalization. Figure 3 clearly illustrates the dynamic impact of varying voucher intensities on social consumption patterns, validating GPLab’s capacity to capture both immediate and decay effects while providing insights into consumption stimulus policy design.

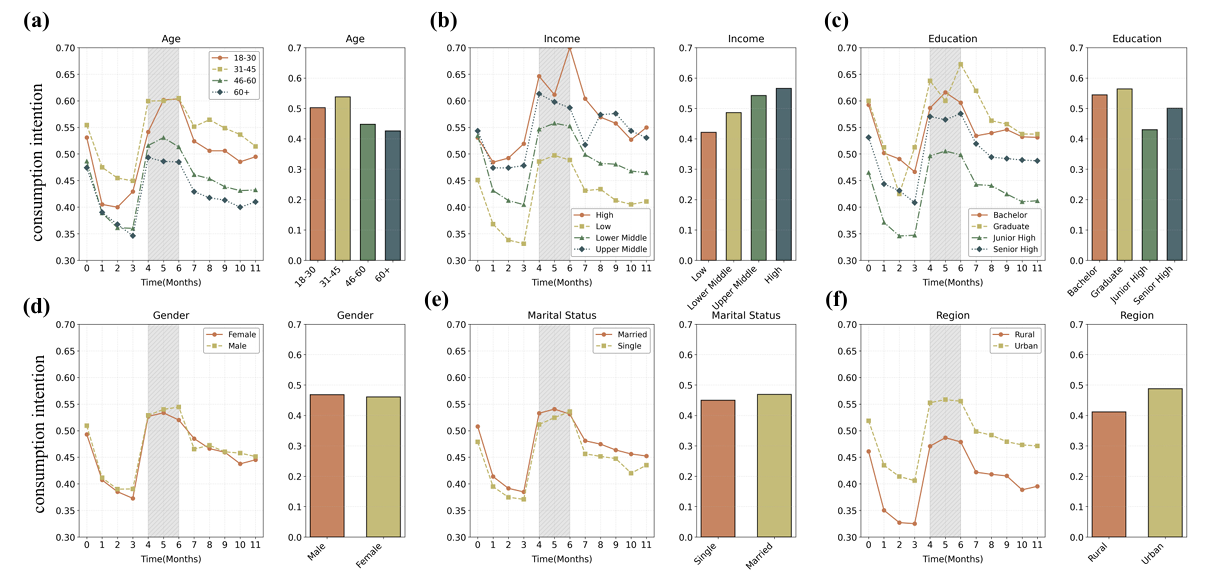

Agent Consumption Behavior Heterogeneity Analysis. As shown in Figure 4, temporal dynamics analysis reveals universal consumption willingness decline pre-implementation, consistent with public health events’ economic suppression. During voucher implementation, all groups demonstrated significant rebounds, confirming policies’ broad positive impact. Post-policy, consumption willingness declined yet generally exceeded pre-policy baselines, indicating sustained influence.

Second, comparing different subgroups reveals:

- Age (a): Young groups aged 18-30 and 31-45 exhibit higher overall consumption willingness, with more pronounced consumption willingness rebounds under policy stimulation and maintained relatively high consumption levels post-policy. Older groups, while also showing improvements, have relatively smaller overall levels and fluctuation ranges.

- Income (b): High-income groups have consumption willingness less affected by environmental factors, consistently maintaining high consumption willingness levels. Middle-income groups also received significant boosts. Low-income groups, while showing increases during policy periods, have relatively weaker overall levels and rebound strength.

- Education Level (c): Groups with higher education levels (such as bachelor’s, graduate degrees) have stronger growth and higher average levels in consumption willingness under policy stimulation.

- Gender (d) and Marital Status (e): Differences in consumption willingness change trends and average levels between genders and between married and unmarried groups are relatively small, but both show positive policy influences.

- Region (f): Urban residents’ consumption willingness overall levels are higher than rural residents.

The results shown in Figure 4 compellingly demonstrate GPLab’s capacity to capture individual behavioral heterogeneity, with demographic differences closely mirroring real population characteristics.

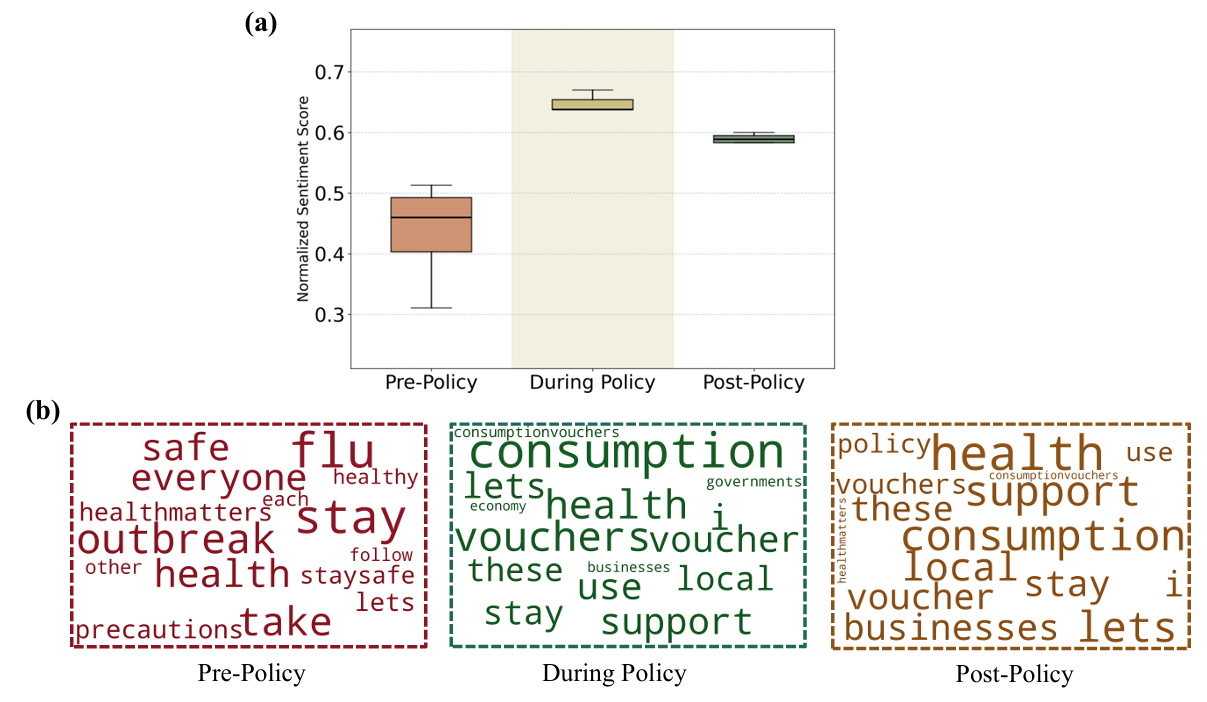

Consumer Emotion Evolution Analysis. As shown in Figure 5, results reveal consumption voucher policies’ substantial impact on social emotions. Pre-implementation, low emotion scores reflected pervasive negative sentiment from public health events. Word cloud analysis indicates public discourse centered on health and safety terms including “flu”, “outbreak”, “safe” and “precautions”. During implementation, emotion scores improved markedly, suggesting voucher distribution effectively bolstered social confidence and mitigated negative emotions. Concurrently, discourse shifted toward economic recovery themes including “consumption”, “vouchers”, and “support”, indicating successful policy attention redirection. Post-implementation, emotion scores declined from peak levels yet exceeded baseline, demonstrating sustained positive effects. Word clouds show “health” dominated discussion, though economic vocabulary maintained prominence, potentially indicating policy-induced consumption habit formation alongside persistent health concerns.

The findings presented in Figure 5 demonstrate GPLab’s effectiveness in capturing social emotion dynamics and discourse evolution under policy interventions.

Case Study: Impact of Carbon Policy on Green Product Promotion

The second experimental scenario focuses on carbon policy effectiveness in promoting green product adoption. We simulate government deployment of multiple policy instruments to guide behavioral change in climate response contexts, specifically examining new energy vehicle adoption.

Social agent modeling and initialization

Agent initialization methods remain consistent with Experiment 1, randomly selecting 500 individuals as simulation subjects for this experiment, generating behavioral decisions driven by the glm-4-9b model. In each month’s simulation, agents make the following behavioral responses based on perceived subsystem information:

- Green electric vehicle purchase intention: a value between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating intention to purchase green vehicles (new energy cars);

- Traditional gasoline vehicle purchase intention: a value between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating intention to purchase traditional vehicles (gasoline cars);

- Social behavior: posting, reposting seen posts, or liking seen posts;

- Consumer stance label: choose ‘green’ or ‘traditional’ to describe current consumer preference type, representing social media positions.

Social subsystem design

Targeting carbon policy’s multi-channel transmission mechanisms, we construct two core subsystems: Economic Environment and Opinion Transmission (Z. Zhang & Han 2024), forming the primary simulation space for policy intervention-behavior feedback.

Economic Environment Subsystem. This subsystem handles green product policy execution and market reaction modeling, executing the following key processes each iteration:

- Implement differential taxation on traditional vehicles while subsidizing green vehicle purchases;

- Process consumer behaviors: aggregate purchase intentions, compute vehicle sales, update market share metrics, and calculate carbon emissions;

- Simulate enterprise responses: model R&D investment adjustments, pricing strategies, cost optimization, and strategic adaptations based on sales performance. Strong green vehicle sales prompt increased green R&D investment, production cost reductions, and moderate price adjustments;

- Model market dynamics: calculate consumer-facing prices incorporating government interventions, track relative price ratios, and generate inputs for subsequent agent decisions.

Opinion Transmission Subsystem. Green product purchase intentions often reflect social network influences. We implement opinion transmission subsystems with small-world network structures (Watts & Strogatz 1998), simulating information diffusion, opinion interaction, and collective attitude evolution under policy contexts.

- Agents perceive information through interest-based and social neighbor recommendations;

- We incorporate a high-influence “government account” as authoritative information source, periodically publishing green policy content with elevated engagement probabilities;

Experimental results

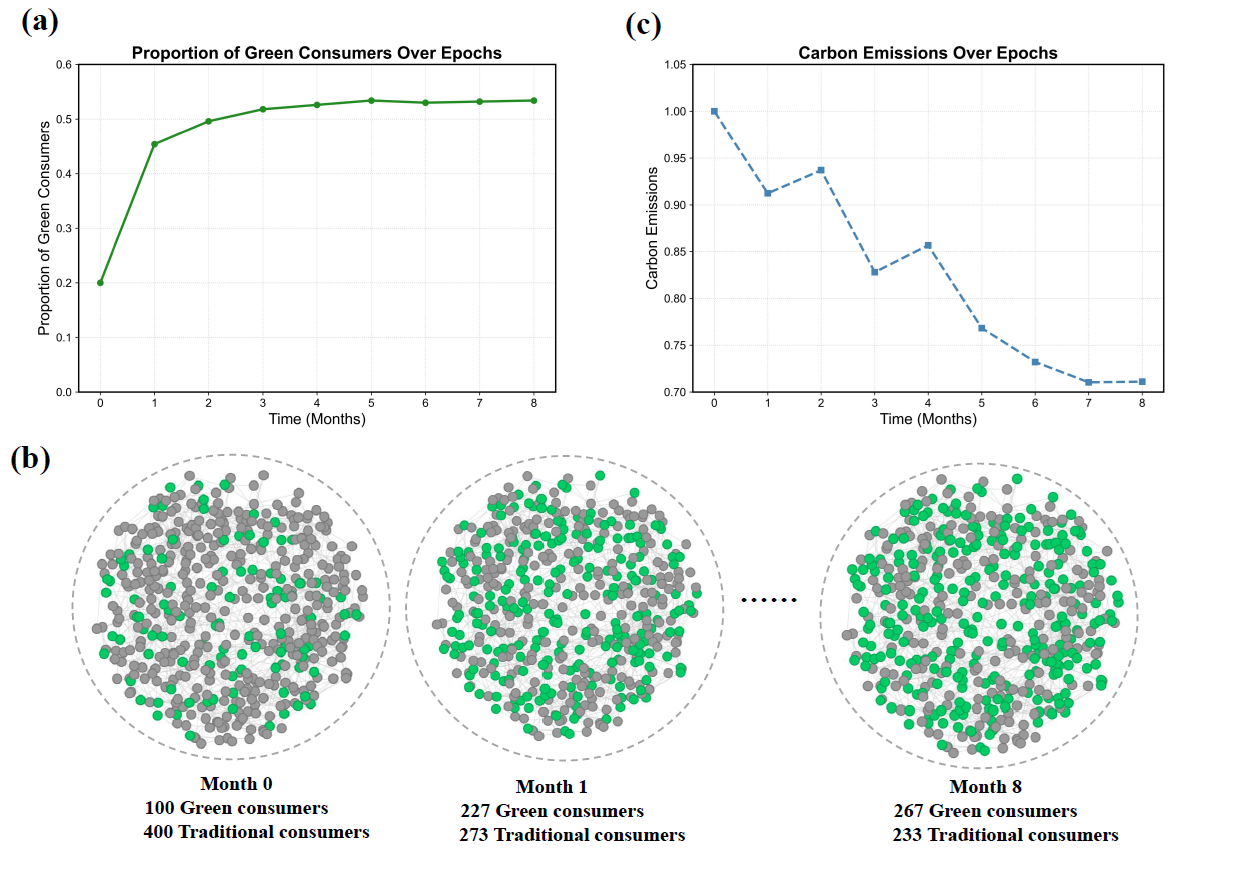

Consumer Type Proportion Changes. As can be observed from Figure 6, carbon policy demonstrated effectiveness in catalyzing green consumption transformation. Initial green consumer proportions stood at merely 20%, with correspondingly elevated carbon emissions. Following policy intervention, green consumer proportions surged (subplot a), reaching 45.4% by month 1 and continuing upward, ultimately stabilizing at 53.4%. This rapid initial increase reflects the activation of agents near decision thresholds through policy incentives, combined with social network cascading effects where early adopters influence their connected neighbors. This micro-level transformation manifests visually in subplot (b): sparse green nodes (green consumers) in pre-policy networks rapidly proliferate following intervention, with corresponding traditional consumer (gray node) decline. Subsequent months reveal opinion polarization and homophily clustering. Concurrently, system-wide carbon emissions exhibit declining trends despite fluctuations (subplot c), with continued reduction as green consumer saturation increases. The zigzag pattern in emissions reflects realistic market dynamics involving three key mechanisms of purchase timing effects, business pricing dynamics, and social network influence. These fluctuations enhance model realism by capturing non-linear market transitions consistent with real-world technology adoption patterns.

The results illustrated in Figure 6 powerfully validate GPLab’s effectiveness in capturing individual behavioral transitions and cross-subsystem policy transmission. The framework not only illustrates carbon policies’ role in promoting green product adoption but also quantifies adoption’s carbon reduction contributions.

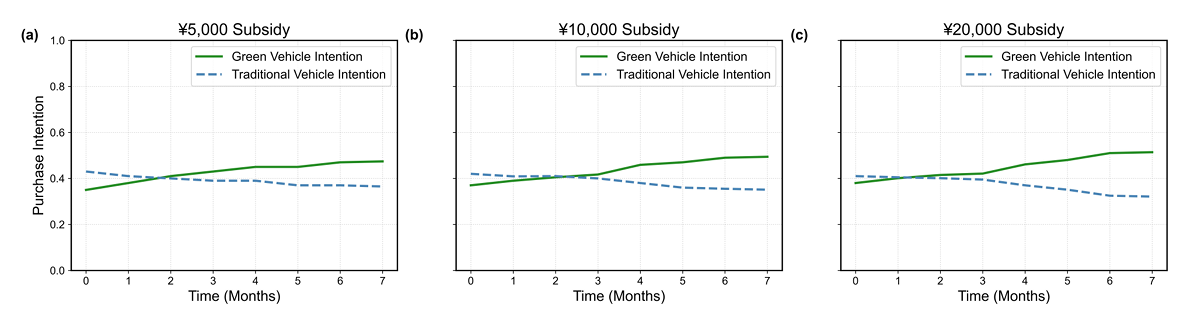

Purchase Intention Changes under Different Subsidy Policies. Comparative analysis illustrated in Figure 7 reveals subsidy intensity’s differential impact on purchase intentions. Across all subsidy levels, green vehicle intentions trend upward while traditional vehicle intentions decline. However, increased subsidies markedly accelerate transformation and elevate final green vehicle acceptance, aligning with empirical expectations.

Discussion

Real-world implications

Our case studies examine two representative policy contexts — consumption voucher distribution during public health emergencies and carbon incentives for green transformation — offering valuable insights for real-world policy design. First, consumption voucher simulations revealed agents’ marked consumption willingness improvement under external subsidies, with both confidence and emotional states exhibiting phased positive responses. These mechanisms, particularly regarding optimal voucher amounts, provide actionable guidance for stimulating consumption during crises. Second, green product promotion analysis revealed differential subsidy effectiveness in cultivating green preferences, with direct price subsidies proving particularly impactful. These findings underscore the importance of coordinating economic incentives with opinion management, creating synergistic behavioral and cognitive effects to enhance policy precision and sustainability.

Micro-level agent consistency evaluation

To rigorously validate agent behavioral authenticity and cognitive stability throughout extended simulations, we introduce formal consistency metrics across three complementary analytical dimensions: cross-temporal behavioral consistency, personality stability, and behavior-trait coherence.

Cross-Temporal Behavioral Consistency. We quantify temporal fluctuations in agent decisions after removing population-level trends. For each agent and behavioral variable, we first compute the detrended series by subtracting the population mean from individual decisions at each time step. We then calculate the coefficient of variation as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean of these detrended values across all time steps for each agent. Lower coefficient values indicate more consistent behavioral patterns across time, with values closer to zero representing perfect consistency and values above 0.3 suggesting fluctuations.

Personality Stability. We employ LLMs to infer Big Five personality traits from each agent’s static profile and decision rationales at every time step, thereby obtaining a personality prediction sequence for each agent over the entire simulation period. We compute two stability metrics for each agent: the personality drift index, calculated as the mean temporal standard deviation across all five personality traits, and the stability rate, measured as the proportion of time steps where trait values remain stable. We then average these metrics across all agents to obtain population-level stability measures. Ideal stability is indicated by drift indices near zero and stability rates approaching 1.0.

Behavior-Trait Coherence. We treat each agent decision at each time step as an independent sample. Using LLMs, we systematically assess whether each decision aligns with the agent’s individual characteristics, then compute coherence rates as the proportion of coherent decisions across all agents and time steps for each subsystem. Values above 0.9 indicate substantial alignment between agent behaviors and their characteristics, with the ideal value of 1.0 representing perfect coherence.

Table 2 presents comprehensive evaluation results across both policy case studies. For cross-temporal behavioral consistency, the coefficient of variation values are 0.230 and 0.218 for consumption voucher and carbon policies respectively, demonstrating stable behavioral patterns over time. These coefficients indicate limited temporal fluctuations in agent decisions. Regarding personality stability, the personality drift indices remain minimal at 0.117 and 0.109, while stability rates achieve 0.922 and 0.935 for the two policy cases respectively, indicating that agents maintain coherent personality profiles across over 92% of temporal measurements. These metrics approach the ideal values of zero drift and unity stability rate, confirming negligible personality variation throughout simulations. For behavior-trait coherence, all subsystem rates demonstrate substantial alignment, with values of 0.944 and 0.961 for economic and opinion subsystems in consumption voucher policy, and 0.959 and 0.948 in carbon policy. These coherence rates, all exceeding 0.94 and approaching the ideal value of 1.0, confirm that more than 94% of agent decisions authentically reflect individual characteristics. Collectively, these quantitative findings provide empirical validation that GPLab-generated agents maintain authentic and stable identities while producing contextually appropriate behavioral responses throughout extended policy simulations.

| Policy Case Study | Cross-Temporal | Personality | Behavior-Trait | ||

| Behavioral | Stability | Coherence | |||

| Coefficient | Drift | Stability | Subsystem 1 | Subsystem 2 | |

| of Variation (\(\downarrow\)) | Index (\(\downarrow\)) | Rate (\(\uparrow\)) | Coherence (\(\uparrow\)) | Coherence (\(\uparrow\)) | |

| Consumption Voucher | 0.230 | 0.117 | 0.922 | 0.944 | 0.961 |

| Carbon Policy | 0.218 | 0.109 | 0.935 | 0.959 | 0.948 |

Scenario transferability evaluation

To validate GPLab’s cross-domain transferability, we extended experimental scope across diversified policy contexts. We generated comprehensive agent datasets encompassing demographic profiles, psychological states, economic conditions, and social relationships using LLMs, subsequently implementing configurations for five policy domains: housing restrictions, medical reform, education equity, health codes, and tax incentives.

Following each simulation, we utilized DeepSeek-R13 to evaluate results across five dimensions: individual heterogeneity, system coordination, indicator correlation, trend rationality, and goal consistency, using standardized scoring criteria as shown in Table 3. The detailed evaluation prompt template is provided in Appendix F.

| Score | Meaning | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Completely Irrational | Contradicts policy goals or common sense significantly. |

| 4 | Irrational | Contains directional errors or major logical flaws. |

| 6 | Fair | Partially reasonable but lacks clarity in mechanisms. |

| 8 | Reasonable | Matches policy logic and demonstrates coherence. |

| 10 | Highly Reasonable | Highly consistent and reflects complex mechanisms. |

To validate the robustness of our framework against prompt variations, we conducted five independent simulation runs for each policy scenario using different prompt template configurations (generated by reordering the four core prompt modules). We report mean scores with standard deviations as confidence intervals. Table 4 shows consistently high scores across scenarios, confirming simulation feasibility and result rationality. The small standard deviations demonstrate that agent behavioral outcomes remain stable despite structural variations in prompt design, validating the framework’s robustness to prompt engineering choices. Despite increased computational demands with expanded agent actions and subsystems (e.g., tax incentive policies with 11 agent actions and 4 subsystems), rationality scores remained robust. This validates GPLab’s universality and transferability across both subsystem configurations and agent role diversity. Notably, the Qwen3-8B model with enhanced reasoning capabilities consumed more tokens yet produced inferior results compared to standard dialogue models, potentially due to over-reasoning tendencies leading to suboptimal decision patterns.

| ID | Policy | Act.a | Sub.a | Score (0-10) | Token Usage (K) | ||||

| GLM | LLaMA | Qwen | GLM | LLaMA | Qwen | ||||

| 1 | Housing Restrict | 3 | 2 | 8.2±0.1 | 7.9±0.2 | 7.5±0.4 | 3,268 | 3,143 | 4,502 |

| 2 | Medical Reform | 3 | 2 | 8.4±0.2 | 7.8±0.3 | 7.8±0.2 | 2,647 | 2,409 | 4,345 |

| 3 | Education Equity | 3 | 2 | 7.8±0.3 | 8.2±0.2 | 8.2±0.3 | 2,768 | 3,011 | 5,060 |

| 4 | Health Code | 9 | 3 | 7.4±0.4 | 7.7±0.3 | 7.6±0.6 | 3,518 | 3,480 | 4,577 |

| 5 | Tax Incentive | 11 | 4 | 8.2±0.5 | 8.1±0.2 | 7.5±0.4 | 5,629 | 5,050 | 7,338 |

Scores represent mean ± standard deviation across 5 independent runs with different prompt configurations. Token Usage is shown in thousands (K). GLM =

glm-4-9b-chat, LLaMA = llama3.1-8B-Instruct, Qwen = Qwen3-8B.

Limitations and future research directions

While GPLab represents significant advancements in both architectural design and methodological innovation, several limitations warrant attention. First, LLMs are prone to hallucinations, which can result in behavioral responses that deviate from realistic contexts, potentially introducing macro-level inconsistencies in extended simulations. Second, the computational demands of long-duration, high-density simulations pose challenges, particularly in resource-constrained environments. In our experiments, we were limited to 500 agent samples due to these constraints. Third, concrete empirical evidence directly comparing the behavioral outcomes of GABM with traditional rule-based ABM implementations remains limited, making it difficult to quantitatively validate the claimed advantages of LLM-driven agents.

Future research should focus on three main directions: (1) developing robust prompting methods and cognitive mechanisms to improve agent consistency and realism, (2) optimizing computational resource allocation via distributed computing to enable larger-scale simulations, and (3) conducting systematic comparative studies between GABM and rule-based ABM by implementing equivalent policy scenarios using both approaches, enabling rigorous comparison of emergent dynamics and policy evaluation accuracy to establish empirical validation for generative agent-based modeling. To facilitate practical deployment, we have created a comprehensive front-end visualization system (see Appendix A), with a performance scaling analysis provided in Appendix G.

Conclusions

This paper introduces GPLab, an innovative framework for policy simulation and evaluation that integrates LLMs with computational social science methodologies. By modeling heterogeneous social agents with cognitive, emotional, and behavioral capabilities, GPLab simulates the dynamic transmission and emergence of policy effects across multi-layered social subsystems. The framework’s modular architecture enhances its flexibility, allowing for tailored simulations across diverse policy contexts. Through systematic case studies and cross-domain experiments, we demonstrate the framework’s effectiveness and broad applicability.

From a methodological standpoint, GPLab overcomes the limitations of traditional ABM by incorporating LLMs, which enhance behavioral realism and introduce strategic complexity. The modular subsystem design further strengthens the framework’s adaptability, enabling specialized modeling for various policy scenarios. Empirically, GPLab shows high credibility and generalization across different domains, establishing a new paradigm for policy evaluation and providing a robust foundation for data-driven, experiment-first policy formulation.

Beyond its role as a policy evaluation tool, GPLab represents a significant interdisciplinary advancement, bridging artificial intelligence, social science, and public policy. As LLM reasoning capabilities and social modeling technologies continue to evolve, we foresee the framework becoming integral to intelligent governance, policy optimization, and social simulation applications.

Notes

- Chinese General Social Survey data link: http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/.↩︎

- glm-4-9b-chat: https://www.modelscope.cn/models/ZhipuAI/glm-4-9b-chat/.↩︎

- https://www.deepseek.com/↩︎

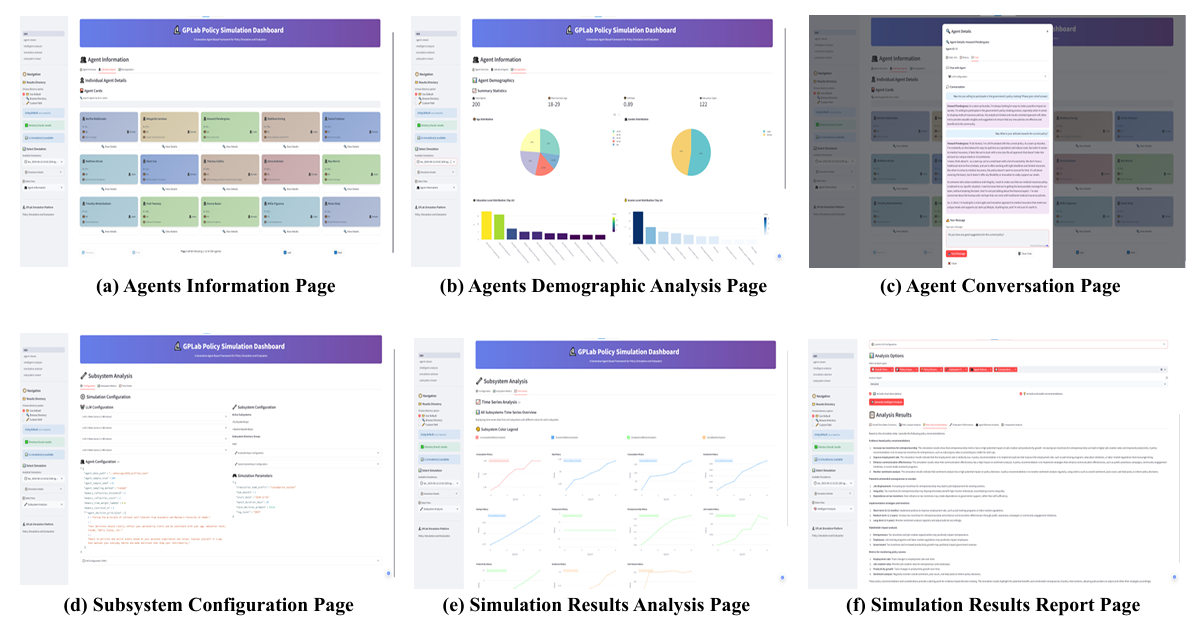

Appendix A: GPLab Frontend Visualization System

To enhance research accessibility, we developed a comprehensive frontend visualization system for GPLab (see Figure 8). This interface enables intuitive monitoring of simulation progress, agent behavior analysis, and policy effect visualization across subsystems.

Appendix B: Agent Behavioral Decision Prompt Example

## Your Static Attributes:

### Basic Information

- Gender: Male

- Age: 27

- Region: Rural

- Marital Status: Married

- Education Level: Junior high and below

- Religious Belief: No religion

- Health Status: very healthy

- Household Registration: Agricultural household

- Annual Personal Income: 20000 CNY

### Psychological Attributes

- Social Trust: Relatively trusts others, believes others might take advantage

- Sense of Fairness: Considers society relatively fair

......

### Social Attributes

- Media Usage: Main information source is the internet, frequently uses TV,

internet, and mobile phones for information

- Internet Usage: Uses the internet daily, has been online in the past six months

......

### Economic Attributes

- Annual Personal Income: 20000 CNY

- Annual Household Income: 50000 CNY

......

## Your Current State:

### Recent Memories & Reflections (Most recent first):

- No relevant memories found for the current situation.

### Current Emotional State: Neutral

## Current Environment:

### From EcoSystemExp1:

- historical_economic_policies: {}

- current_economic_policy: {"date": "2020-12-01", "policy_text": ""}

### From OpinionSystemExp1:

- Recommended Posts: {}

- historical_news_headlines: {}

- current_news_headline: {"date": "2020-12-01", "headline_text":

"Seasonal flu outbreak in a city, current prevention situation is urgent!"}

## Your Task:

Based on your attributes, current state (memories, emotion), and the environment,

decide on your actions for the current time step.

You MUST respond ONLY with a single JSON object. The JSON object should have keys

corresponding to the active social subsystems you interact with.

For each subsystem, provide the requested decision attributes.

Include a 'reasoning' field explaining *why* you made these decisions based on

the provided context.

Your decisions must follow these principles:

- Your decisions should clearly reflect your personality traits and be consistent

with your age, education level, income, family status, etc.

- React to policies and social events based on your personal experiences and values.

Express yourself in a way that matches your everyday habits and make decisions

that show your individuality.

### Active Subsystems and Required Decisions:

- **EcoSystemExp1**: Requires decisions for: consumption_willingness,

savings_preference, work_willingness

- **OpinionSystemExp1**: Requires decisions for: social_actions

### Response Format (JSON ONLY):

{

"reasoning": "Explain why you're doing it",

"EcoSystemExp1": {

"consumption_willingness": "<a number between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating your

willingness to consume>",

"savings_preference": "<a number between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating your

willingness to save>",

"work_willingness": "<a number between 0.0 and 1.0 indicating your

willingness to work>"

},

"OpinionSystemExp1": {

"social_actions": "[{\"action\": \"post\", \"content\": \"<your post content

string>\"}, {\"action\": \"like\", \"post_id\": \"<ID of

post to like>\"}, {\"action\": \"repost\", \"post_id\":

\"<ID of post to repost>\"}]"

}

}

Appendix C: Agent Memory Reflection Prompt

Given the following observations:

{memory_str}

Generate 2 high-level insights based on these observations.Appendix D: Agent Emotion Extraction Prompt

Based on recent memory and actions, describe current emotional state:

{history}

Emotional State:Appendix E: Agent Behavioral Decision Algorithm

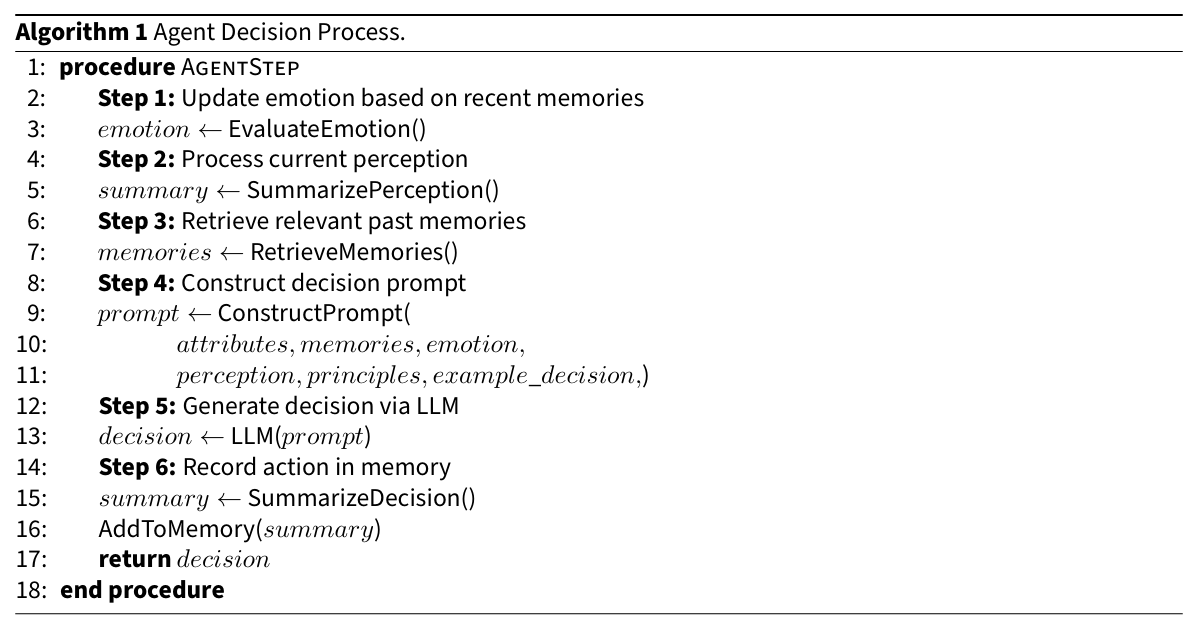

The agent behavioral decision process follows a systematic approach as detailed in Algorithm 1. This algorithm integrates emotion evaluation, memory retrieval, and LLM-based decision generation to simulate realistic human-like behaviors in policy scenarios.

Appendix F: Simulation Effect Evaluation Prompt

You are a policy evaluation expert. Please score policy simulation results

across multiple dimensions based on simulation data and policy logic matching.

### Scoring Dimensions (5-point scale):

1. Goal Consistency: Policy content and indicator change matching

2. Trend Rationality: Whether changes meet theoretical expectations

3. System Coordination: Logical chains between subsystems

4. Heterogeneity Reflection: Different group responses

5. Indicator Correlation: Causal relationships between indicators

### Scoring Scale:

- 2: Completely Unreasonable

- 4: Unreasonable

- 6: Fair

- 8: Reasonable

- 10: Highly Reasonable

### Output Requirements:

For each dimension: provide score and brief rationale.

Calculate average score across 5 dimensions.

Appendix G: Performance Scaling Analysis of GPLab Framework

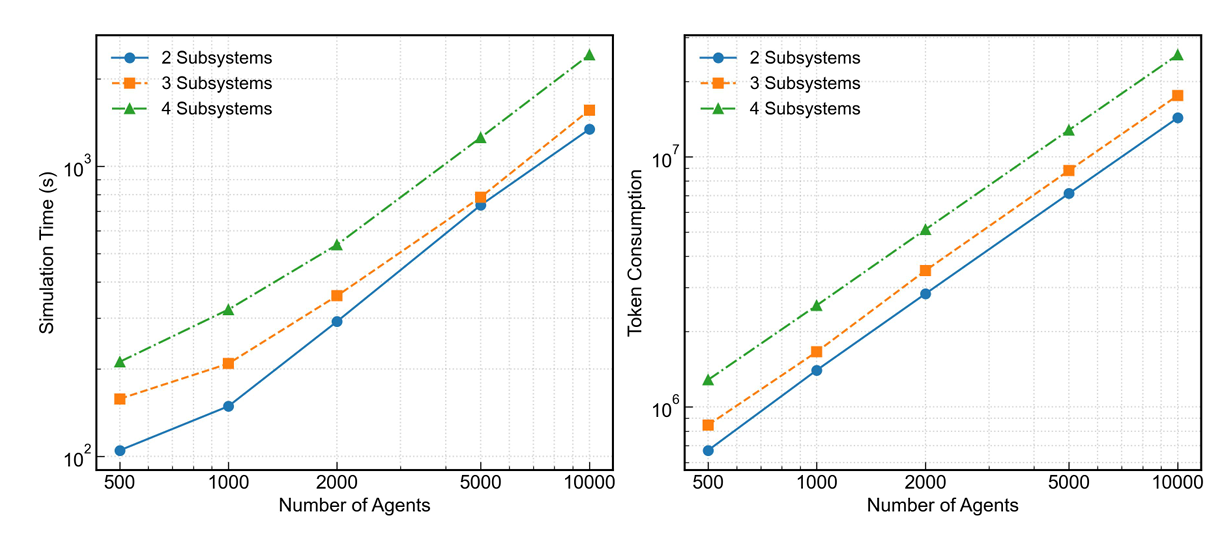

Figure 9 presents our framework’s performance scaling characteristics. Analysis reveals predictable increases in both simulation time and token consumption with agent and subsystem expansion, demonstrating the framework’s scalability patterns and computational requirements.

References

ACHIAM, J., Adler, S., Agarwal, S., Ahmad, L., Akkaya, I., Aleman, F. L., Almeida, D., Altenschmidt, J., Altman, S., Anadkat, S., & others. (2023). Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2303.08774.

AHER, G. V., Arriaga, R. I., & Kalai, A. T. (2023). Using large language models to simulate multiple humans and replicate human subject studies. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

AJZEN, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t]

ANGRIST, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

ATHEY, S., & Imbens, G. W. (2017). The state of applied econometrics: Causality and policy evaluation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 3–32. [doi:10.1257/jep.31.2.3]

BALES, R. F. (1950). Interaction Process Analysis: A Method for the Study of Small Groups. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

CHEN, W., Su, Y., Zuo, J., Yang, C., Yuan, C., Qian, C., Chan, C.-M., Qin, Y., Lu, Y., Xie, R., Liu, Z., Sun, M., & Zhou, J. (2023). Agentverse: Facilitating multi-agent collaboration and exploring emergent behaviors in agents. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2308.10848

CHUANG, Y.-S., Goyal, A., Harlalka, N., Suresh, S., Hawkins, R., Yang, S., Shah, D., Hu, J., & Rogers, T. (2024). Simulating opinion dynamics with networks of LLM-based agents. In K. Duh, H. Gomez, & S. Bethard (Eds.), Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024 (pp. 3326–3346). Mexico City: Association for Computational Linguistics. [doi:10.18653/v1/2024.findings-naacl.211]

D’AURIA, M., Scott, E. O., Lather, R. S., Hilty, J., & Luke, S. (2020). Assisted parameter and behavior calibration in agent-based models with distributed optimization. In Y. Demazeau, T. Holvoet, J. M. Corchado, & S. Costantini (Eds.), Advances in Practical Applications of Agents, Multi-Agent Systems, and Trustworthiness. The PAAMS Collection (pp. 93–105). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [doi:10.1007/978-3-030-49778-1_8]

DEVLIN, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In J. Burstein, C. Doran, & T. Solorio (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (pp. 4171–4186). Minneapolis, MN: Association for Computational Linguistics.

FLORIDI, L., & Chiriatti, M. (2020). GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds and Machines, 30, 681–694. [doi:10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1]

GAMAL, Y., Elsenbroich, C., Gilbert, N., Heppenstall, A., & Zia, K. (2024). A behavioural agent-based model for housing markets: Impact of financial shocks in the UK. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 27(4), 5. [doi:10.18564/jasss.5518]

GHAFFARZADEGAN, N., Majumdar, A., Williams, R., & Hosseinichimeh, N. (2024). Generative agent-based modeling: An introduction and tutorial. System Dynamics Review, 40(1), e1761. [doi:10.1002/sdr.1761]

GUO, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J., Zhang, R., Xu, R., Zhu, Q., Ma, S., Wang, P., Bi, X., & others. (2025). Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2501.12948

HAO, Y., & Xie, D. (2025). A multi-LLM-agent-based framework for economic and public policy analysis. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2502.16879

HONG, S., Zheng, X., Chen, J., Cheng, Y., Wang, J., Zhang, C., Wang, Z., Yau, S. K. S., Lin, Z., Zhou, L., & others. (2023). Metagpt: Meta programming for multi-agent collaborative framework. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2308.00352

ISHIKAWA, S., & Yoshino, A. (2025). AI with emotions: Exploring emotional expressions in Large Language Models. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Natural Language Processing for Digital Humanities. [doi:10.18653/v1/2025.nlp4dh-1.51]

JIA, J., & McNamara, P. E. (2024). Information interventions and willingness to pay for PICS bags: Evidence from Sierra Leone. Food Policy, 129, 102760. [doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2024.102760]

JONES, B. D. (2002). Bounded rationality and public policy: Herbert A. Simon and the decisional foundation of collective choice. Policy Sciences, 35(3), 269–284. [doi:10.1023/a:1021341309418]

KREMMYDAS, D., Athanasiadis, I. N., & Rozakis, S. (2018). A review of agent based modeling for agricultural policy evaluation. Agricultural Systems, 164, 95–106. [doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2018.03.010]

LEMPERT, R. (2002). Agent-based modeling as organizational and public policy simulators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(3), 7195–7196. [doi:10.1073/pnas.072079399]

LEWIS, P., Perez, E., Piktus, A., Petroni, F., Karpukhin, V., Goyal, N., Küttler, H., LEWIS, M., Yih, W.-t., Rocktäschel, T., Riedel, S., & Kiela, D. (2020). Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. In H. Larochelle, M. Ranzato, R. Hadsell, M. F. Balcan, & H. Lin (Eds.), Advances in neural information processing systems (Vol. 33, pp. 9459–9474). [doi:10.18653/v1/2021.naacl-main.200]

LI, G., Hammoud, H., Itani, H., Khizbullin, D., & Ghanem, B. (2023). Camel: Communicative agents for "mind" exploration of large language model society. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 51991–52008.

LI, H., Gong, R., & Jiang, H. (2025). Political actor agent: Simulating legislative system for roll call votes prediction with large language models. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. [doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i1.32017]

LI, N., Gao, C., LI, M., LI, Y., & Liao, Q. (2024). EconAgent: Large language model-empowered agents for simulating macroeconomic activities. Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. [doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.829]

LIU, Y., Chen, X., Zhang, X., Gao, X., Zhang, J., & Yan, R. (2024). From skepticism to acceptance: Simulating the attitude dynamics toward fake news.Proceedings of the Thirty-Third International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-24.

MARK, M. M., Cooksy, L. J., & Trochim, W. M. (2009). Evaluation policy: An introduction and overview. New Directions for Evaluation, 2009(123), 3–11. [doi:10.1002/ev.302]

MARVUGLIA, A., Bayram, A., Baustert, P., Navarrete Gutiérrez, T., & Igos, E. (2022). Agent-based modelling to simulate farmers’ sustainable decisions: Farmers’ interaction and resulting green consciousness evolution. Journal of Cleaner Production, 332, 129847. [doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129847]

MOU, X., Wei, Z., & Huang, X. (2024). Unveiling the truth and facilitating change: Towards agent-based large-scale social movement simulation. In L.-W. Ku, A. Martins, & V. Srikumar (Eds.), Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024 (pp. 4789–4809). Bangkok: Association for Computational Linguistics. [doi:10.18653/v1/2024.findings-acl.285]

NESPECA, V., Comes, T., & Brazier, F. (2023). A methodology to develop agent-based models for policy support via qualitative inquiry. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 26(1), 10. [doi:10.18564/jasss.5014]

ORTONY, A., Clore, G. L., & Collins, A. (2022). The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

PARK, J. S., O’Brien, J. C., Cai, C. J., Morris, M. R., Liang, P., & Bernstein, M. S. (2023). Generative agents: Interactive simulacra of human behavior. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. [doi:10.1145/3586183.3606763]

PARK, J. S., Popowski, L., Cai, C., Morris, M. R., Liang, P., & Bernstein, M. S. (2022). Social simulacra: Creating populated prototypes for social computing systems. Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology. [doi:10.1145/3526113.3545616]

PIAO, J., Yan, Y., Zhang, J., Li, N., Yan, J., Lan, X., Lu, Z., Zheng, Z., Wang, J. Y., Zhou, D., & others. (2025). AgentSociety: Large-scale simulation of LLM-Driven generative agents advances understanding of human behaviors and society. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2502.08691. [doi:10.2139/ssrn.5954414]

SCHIRMER, W., & Michailakis, D. (2018). Luhmann’s sociological systems theory and the study of social problems. In A. J. Trevino (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Social Problems (pp. 221–240). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [doi:10.1017/9781108656184.014]

SQUIRE, L. R., & Wixted, J. T. (2011). The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since HM. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 34(1), 259–288. [doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113720]

STEINBACHER, M., Raddant, M., Karimi, F., Cuena, E. C., Alfarano, S., Iori, G., & Lux, T. (2021). Advances in the agent-based modeling of economic and social behavior. SN Business & Economics, 1(1), 99. [doi:10.1007/s43546-021-00103-3]

TISUE, S., & Wilensky, U. (2004). Netlogo: A simple environment for modeling complexity. International Conference on Complex Systems, 21, 16–21.

TSIATSIOS, G. A., Kollias, I., Leventides, J., & Melas, E. (2024). An agent-based model of consumer demand. Bulletin of Economic Research, 76(4), 935–950. [doi:10.1111/boer.12458]

VON Essen, M., & Lambin, E. F. (2023). Agent-based simulation of land use governance (ABSOLUG) in tropical commodity frontiers. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 26(1), 5. [doi:10.18564/jasss.4951]

WANG, G., Hamad, R., & White, J. S. (2024). Advances in difference-in-differences methods for policy evaluation research. Epidemiology, 35(5), 628–637. [doi:10.1097/ede.0000000000001755]

WANG, G., Xie, Y., Jiang, Y., Mandlekar, A., Xiao, C., Zhu, Y., Fan, L., & Anandkumar, A. (2023). Voyager: An open-ended embodied agent with large language models. NeurIPS 2023 Foundation Models for Decision Making Workshop.

WANG, L., Ma, C., Feng, X., Zhang, Z., Yang, H., Zhang, J., Chen, Z., Tang, J., Chen, X., Lin, Y., Zhao, W. X., Wei, Z., & Wen, J. (2024). A survey on large language model based autonomous agents. Frontiers of Computer Science, 18(6), 186345. [doi:10.1007/s11704-024-40231-1]

WANG, Y., Zhang, Q., Sannigrahi, S., Li, Q., Tao, S., Bilsborrow, R., Li, J., & Song, C. (2021). Understanding the effects of China’s agro-environmental policies on rural households’ labor and land allocation with a spatially explicit agent-based model. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 24(3), 7. [doi:10.18564/jasss.4589]

WATTS, D. J., & Strogatz, S. H. (1998). Collective dynamics of ’small-world’ networks. Nature, 393(6684), 440–442. [doi:10.1038/30918]

WEI, Y.-M. (2025). Integrated assessment platform (C3IAM) and overall design of coupling technology. In Carbon Mitigation System Engineering: Principles, Methods and Practices (pp. 177–195). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [doi:10.1007/978-981-95-0371-1_8]

WILLIAMS, R., Hosseinichimeh, N., Majumdar, A., & Ghaffarzadegan, N. (2023). Epidemic modeling with generative agents. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2307.04986.

XIAO, B., Yin, Z., & Shan, Z. (2023). Simulating public administration crisis: A novel generative agent-based simulation system to lower technology barriers in social science research. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2311.06957

YAO, J., Zhang, H., Ou, J., Zuo, D., Yang, Z., & Dong, Z. (2025). Social opinions prediction utilizes fusing dynamics equation with LLM-based agents. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 15472. [doi:10.1038/s41598-025-99704-3]

YAO, S., Zhao, J., Yu, D., Du, N., Shafran, I., Narasimhan, K., & Cao, Y. (2023). React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

ZHANG, X., Lin, J., Sun, L., Qi, W., Yang, Y., Chen, Y., Lyu, H., Mou, X., Chen, S., Luo, J., Huang, X., Tang, S., & Wei, Z. (2024). Electionsim: Massive population election simulation powered by large language model driven agents. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2410.20746

ZHANG, Z., & Han, Z. (2024). Exploring coevolution in the diffusion of green products between consumers and enterprises - An agent-based model of two-layer heterogeneous networks. Journal of Cleaner Production, 450, 141689. [doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141689]