Abstract

Abstract

- In this paper, we propose a novel approach to exploring the destimgatisation process, an agent-based model called the destigmatization model (DSIM). In the DSIM, we demonstrate that, even if individual interactions (intergroup contact) are based on rules of the self-fulfilling prophecy, it can lead to destigmatisation. In a second study, we empirically verify a prediction that there is a positive relationship between minority group size and perceived stigmatization. Finally, we confirm that DSIM successfully implements Allport's (1954) four moderators, in turn decreasing the level of perceived stigma of the minority group. Interestingly, however, some of Allport's moderators influence the speed of destigmatisation, rather than having a lasting impact on the process of prejudice reduction. The findings suggest that moderators of 'intergroup contact' can function in one of two ways, either by improving how much contact helps to reduce stigmatization or by improving how quickly destigmatization can occur.

- Keywords:

- Destigmatization, Intergroup Contact, Social Psychology

Introduction

Introduction

- 1.1

- Social stigma has long been recognized as a problem. The continuing consequences of its negative effects on mental health (Harrell 2000), physical health (Clark et al. 1999), academic achievement (Steele 1997) and other areas such as social mobility and access to housing, education, and employment are also well-established (see Major and O'Brien 2005). It is, therefore, no surprise to find that the group processes literature has focused on identifying ways in which we can reduce intergroup bias, social exclusion, and stigmatization (Abrams, Christian and Gordon 2007; Wu et al. 2008; Finkelstein, Lapshin and Wasserman 2008). However, with few exceptions, the methodology used in existing accounts does not allow researchers to simultaneously examine the individual-level and group-level effects in an integrated model (cf. Abrams and Christian 2007; Christ, Hewstone, Tausch, Wagner, Voci, Hughes and Cairns 2010; Abrams 2010). Herein, we apply such a novel approach to advance our understanding of intergroup relations, introducing the theoretical approach of an agent-based model (ABM).

Agent-based Model Approaches to Social Phenomena

- 1.2

- In an ABM, a large number of "agents" interact with one another according to a set of simple rules. Such models are frequently used to examine 'how' macro-level (social) phenomena emerge from micro-level (individual) interactions; and these simulations have been used to explore a spectrum of social issues, such as social segregation (Schelling 1971; Henry et al. 2011), dating and mate selection (Kalik and Hamilton 1986), opinion formation (Hegselmann and Krause 2002), and religious choice (Iannaccone and Makowsky 2007). Importantly, these models generate innovative explanations for the respective social phenomena, ones that would have been difficult to discover relying on traditional experimental paradigms. For example, Schelling (1971) demonstrated that segregation can emerge from very minor individual-level preferences in the social make-up of neighborhoods. Similarly, Iannaccone and Makowsky (2007) showed that religious preferences can emerge and be maintained, even in populations that frequently gain and lose members, irrespective of religious orientation of respective populations. More recently, in an extension of Schelling's work, Henry et al. (2011), in a study of social segregation and network structure, found that relationships are more likely to exist between actors/agent with higher degrees of similarity. Agents might not have a preference for a homogenous (like-mindedness) network, but if biased against dissimilar others, segregation can also take place. In general, the evidence supports the development of more complex models to explore interactions and examine the 'individual attributes of network actors' (pp. 8605).

- 1.3

- In our view, stigmatization is an important factor and often goes hand-in-hand with social segregation. Here, we apply an ABM approach to further our understanding of the processes motivating the reduction of social stigma, focusing specifically on the interactions between individuals' attitudes and social perceptions (expectations and desire for like-mindedness/diversity), and how these affect the process of destigmatization. We term the model, the destigmatization model (DSIM). Moreover, the current paper not only presents an agent-based model, but goes beyond to report an empirical verification of a prediction from such a model.

The Social Psychological Framework for the Study

- 1.4

- In his seminal paper, Allport (1954) argues that contact between members of previously hostile groups reduces prejudice, a precursor to destigmatization (see also Williams 1947). However, according to Allport (1954), intergroup contact is only effective if four 'optimal conditions' are met: Similar socio-economic status between the majority (the in-group) and minority (the out-group) group members/agents; intergroup cooperation (e.g., the establishment of circumstances leading to cooperative contact wherein there is equal status between group members); common goals/shared interests between the groups (e.g., the establishment of circumstances leading to goal-oriented contact wherein there is equal status between group members); and the support of authorities, law, or custom (e.g., the creation of situations that allow for interaction and the provision of support by relevant authorities).

- 1.5

- Following 50 years of research, the utility of Allport's 'contact hypothesis' was examined in a meta-analysis by Pettigrew and Tropp (2006). In their analysis, the researchers systematically tested 713 independent samples from 515 intergroup 'contact' studies. The results support the central hypothesis of Allport's theory, which is that intergroup contact decreases intergroup bias in a broad range of social settings. However, they also found that all 'optimal conditions' decreased stigmatization of minority groups, although they were not necessary preconditions for it to occur. Moreover, they reported that institutional support had the strongest effect of the four conditions, but that its influence is only possible if the groups are of equal status. In contrast, if the groups are competitive, institutional support is more likely to have a detrimental effect, meaning that it will not to lead to destigmatization of the minority group. Based on this, Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) concluded that the optimal conditions 'function' together in order to have a facilitatory effect, despite the fact that there is evidence that each condition, on its own, can reduce or moderate the level of stigma felt by the minority group. But, to the extent to which these aspects directly influence positive attitudes that may evolve into contact; and the effect of the optimal conditions might have on social interactions longitudinally remains unclear.

- 1.6

- In one such example, Jackman and Crane (1986) found that white Americans who had regular contact with black Americans of high socio-economic status reported more positive attitudes towards black Americans, than did white Americans who had contact with Black Americans of lower socio-economic status. (This pattern was repeated across the conditions.) Concerning the "cooperation" condition, Desforges et al. (1997) introduced a confederate who posed as a member of social group that the participants reported being biased against. Here, the researchers showed that cooperation between confederate and participant led to positive attitude change. The recognition of common goals also has a positive effect upon the capacity of intergroup contact to reduce prejudice between members of differing social groups. Note that it can be difficult to distinguish between cooperation and common goals, as most experimental manipulations that 'supply' a common goal to study participants also involve some sort of cooperation (cf. Chu and Griffey 1985). As far as we are aware, the only non-survey study of intergroup contact that separates this potential confound is that of Chu and Griffey (1985). In interracial sports teams, members requiring no direct cooperation (e.g., fencing teams) had no significant attitude differences to those requiring a cooperative effort (e.g., football teams). Thus, the two factors, cooperation and common goals, are independent though frequently co-exist. Finally, turning attention to 'support from authorities recognized by both groups', Parker (1968) examined interracial attitudes of a mixed race church, and found that 'exceptional leadership' displayed by the minister led to good interracial attitudes. While there is a large cross-sectional intergroup contact literature, unfortunately there are no experimental studies in which the conditions of contact are simultaneously tested (cf. Pettigrew and Tropp 2006). We have, therefore, reported only selected experimental studies. Such research focuses on direct contact (i.e., actor-to-actor; cf. Turner et al. 2008); hence we focus on this form of intergroup interaction.

- 1.7

- Finally, it is worth noting that to the best of our knowledge no agent based models have directly studied the effects of interactions between minority and majority groups within the framework of Allport's 'contact hypothesis'. However, interactions between minority and majority groups are a frequent theme in agent-based models, most notably in the area of political science (e.g. Miodownik and Cartrite (2010) on how to deal with demands of ethnic minority groups for greater regional autonomy; or Bhavnani, Miodownik, & Choi (2011) on the levels of violence in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict)

The Current Research

- 1.8

- In our study, we develop an agent-based model to simulate the effects of intergroup contact, and also to explore the influence of Allport's four moderators. In this way, it is possible to test whether the four moderators operate together; and, also to tease out the unique contribution of each moderator to the reduction stigma within the intergroup context (Pettigrew and Tropp 2006). The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: We introduce DSIM, including the implementation of Allport's optimal conditions. In the first set of simulations (Study 1), we demonstrate that, indeed, DSIM implements a destigmatization process. Interestingly, the simulations show that the extent to which the minority group is stigmatized decreases with increasing group/population size (of the minority group). This prediction is empirically confirmed in Study 2, further validating the model. Then, in Study 3, the amount of contact is manipulated more directly by increasing the size of the 'neighborhoods'—the social space—in which agents interact with each other. This allows us to consider the effects of more extreme levels of intergroup contact on destimgatization. Finally, Study 4 examines the influence of Allport's (1954) four "optimal conditions", both in terms of the magnitude of their individual contribution, as well as their influence on the 'speed of destigmatization' within the model. The simulations reveal that "status" has qualitatively different effect on the DSIM's behavior; and while 'cooperation', 'authority' and 'common goals' speed up the process destigmatization, they do not impact the overall level of perceived stigma.

Destigmatization Model (DSIM)

Destigmatization Model (DSIM)

- 2.1

- The model consists of two groups of agents, a majority social group and minority social group. Each agent is placed on a spatial grid and is randomly allocated to either the mainstream non-stigmatized majority group or to the stigmatized minority group. Each agent possesses two numerical attributes, with a value ranging from -1 to 1. One value represents the agent's "opinion" of the non-stigmatized majority group, while the other value represents the agent's "opinion" of the stigmatized minority group. The agent's opinion scores express its attitudes towards the respective group ranging from, "I really dislike this group" (-1) to "I really like this group" (1). In order to realize social "contact" between agents on an individual-level agents interact with a subset of other agents (see methodology section). Moreover, the interaction between two agents can either be perceived as positive or negative. Importantly, however, both agents perceive the given interaction in the same way. We have implemented the parameter in this way, so that we might maintain a level of consistency in social perceptions. Thus, up to this point, the set-up of the model follows a minimal modeling principle (e.g. only two "social groups" of agents and only single values for opinions about social groups).

- 2.2

- To devise rules for the interactions between minority and majority group agents, we drew on the self-fulfilling prophecy theory (SFP) of social interactions (see Jussim et al. 2000). Self-fulfilling prophecy consists of three steps (e.g., Jussim 1986). An individual ("perceiver") develops expectations about others ("targets"); next, perceivers' expectations influence the way in which they treat the target individuals; then, targets react to this treatment, with behavior that confirms their expectation. This division into perceivers and targets is arbitrary, as in such a didactic interaction both parties are perceivers and targets simultaneously. It should be highlighted that the SFP theory normally is assumed to contribute to maintaining stigma rather than reducing stigma. However, as we will show, under certain conditions SFP-guided interactions can lead to destigmatization.

- 2.3

- The SFP assumptions are implemented in the DSIM in the following way: First, each agent generates an expectation of the quality of the interaction, which is equal to the opinion an agent holds of the other agent's social group. Second, the quality of the interaction (common to both agents) is influenced by this expectation about the interaction. However, in order to take into account the reciprocal nature of the interaction, the quality of the interaction must also be affected by the other agent. The simplest way of implementing this is to average between the opinions of the two agents of each other:

Quality of interaction = (opinion1 + opinion2) / 2 + random(-1, 1) (1) Random (-1,1) is a random number between -1 and 1 and takes into account that the quality of interactions, in reality, is influenced by numerous factors that we modeled as random noise. Opinion1 is the opinion that the first agent holds of the second agent and Opinion2 is the opinion that the second agent holds of the first agent. Finally, to complete the cycle of the self-fulfilling prophecy model, the opinion of the involved agents is changed through the simple rule:

If quality of interaction > opinion then increase opinion

If quality of interaction < opinion then decrease opinion(2) - 2.4

- In other words, if the interaction turns out to be more positive than expected, the agent improves its opinion of its partner's social group; however, if it turns out more negative than expected then its opinion of that social group decreases. (Opinions of the interaction generalize to the group.) Hence, the opinions move closer to the quality of interaction implementing the self-fulfilling prophecy. The change of opinion in all simulations was set to 0.0001. In pilot studies, we found that this value balanced issues of a convergence into a stable state of the model, and at a reasonable length of simulation time.

- 2.5

- Finally, at the beginning of each simulation, the agents' opinions have to be initialized. The opinions of their own group were positive (+0.9). In contrast, the attitude of majority group agents towards the minority group agents was set to -0.9, making the minority group a stigmatized group from the onset of the simulation. Importantly, minority group agents initially have a positive opinion (+0.9) towards the majority group agents. This setting is motivated by evidence that stigmatized groups can have positive attitudes towards the majority group, if the perceived group permeability allows disadvantaged groups to see the majority group status as within their reach (see Ellemers et al. 1988; Ellemers et al. 1993; Verkuyten and Reijerse 2008)[1]. In the next section, we will introduce how Allport's (1954) moderators are integrated into DSIM.

Extending DSIM with Allport's Conditions

- 2.6

- Status. The quality of interactions is determined by the average of the agents' opinions of each other, as indicated above. Unequal status of group members is implemented by weighting the two opinions differently. In order to make the majority member's opinion more important in determining the nature of the social interaction, as suggested by self-fulfilling prophecy concepts, we used the following equation:

Quality of interaction = (opinion1 * (1 - status) + opinion2 * status) / 2 + random (-1,1) (3) Opinion1 represents the opinion of the majority group agent's opinion in the interaction, while opinion2 is the opinion of the minority group agent of the interaction. The value of the status variable ranges from 0 (i.e., the minority agent's opinion has no effect on the interaction) to 0.5 (i.e., the minority agent's opinion has as much effect on the interaction as the majority agent's opinion does).

- 2.7

- Common goals. To implement the 'common goals' variable, the agents are arbitrarily assigned one of two abstract goal groups. Each agent is assigned to either Goal "A" or Goal "B". Agents retain the same goal throughout the simulation. The recognition of the goal is randomized, with the probability of recognition as a new variable "common goals". In a given cycle, if agents recognize that they hold a common goal, those agents interact an additional time during that cycle (as an indication of liking for that other agent). Agents do not remember one another's goals from cycle to cycle, so this test for recognition is made each cycle regardless of the outcome of the test in previous cycles.

- 2.8

- Intergroup cooperation. The possibility of acting in the pursuit of a common goal shared between agents was implemented by designating some interactions to be 'cooperation attempts'. In a 'cooperation attempt', more is at stake, so any change of opinion, whether positive or negative, is doubled to represent the greater risk associated with it. In order to vary the level of cooperation in a given simulation, we manipulated the chance that each interaction could be a 'cooperative' opportunity.

- 2.9

- Institutional support. To implement the notion of "institutional support" for intergroup interactions, some agents were designated "key authorities". Because institutional support is only effective when both social groups recognize the expertise of the authority, our authority agents belong to both the stigmatized and non-stigmatized groups, and therefore can function in both capacities. An important consequence of this, however, is that an authority agent never has an intergroup interaction itself. Rather, the sanctioning of intergroup interactions by these authority agents increasing the rate of intergroup interactions between minority and majority agents in their vicinity. In terms of implementation, any intergroup interaction that occurs within three grid spaces of one or more of the authority agents shall then occur an additional time each cycle. The level of institutional support in a given simulation was varied by altering the number of authority agents placed on the grid at the start of the simulation.

Study 1: Basic Behavior of the DSIM

Study 1: Basic Behavior of the DSIM

- 3.1

- In this study, we aim to show that intergroup contact between agents who are members of stigmatized groups and agents who are members of non-stigmatized groups leads to destigmatization. This will confirm that the DSIM models the 'contact effect' as outlined by Allport (1954). In addition, we sought to examine minority groups of different population sizes (see also Queller and Smith 2002; McIntyre, Paolini and Hewstone 2010). The manipulation of group size aims to demonstrate that the DSIM generalizes across different group ratios. Conversely, this variation forms an indirect way of changing the amount of contact between the in-group and out-group agents. Larger numbers of stigmatized minority groups will lead to a greater number of intergroup interactions, simply because there are more minority agents to be involved in these interactions. For DSIM to be successful, the simulations need to show a decrease in the stigmatization of minority agents with more intergroup contact.

Method

- 3.2

- The model consisted of 22 × 22 grid, with a total of 484 agents divided into two social groups. Simulations used one of four population sizes for minority groups. In a given simulation the minority group had: 30, 60, 90, or 120 agents. Additionally, agents interacted with their eight immediate neighbors. Finally, simulations were run for 5,000 cycles, and each simulation was repeated ten times.

Results

- 3.3

- In order to interpret the findings in terms of the 'contact hypothesis', it is necessary to understand the way in which the agents' opinions motivate the emerging patterns. To achieve this, we shall present a typical simulation to illustrate the general pattern of the result. Then, we shall turn to discuss the behavior of three agents, before going on to look at the overall findings of the study.

- 3.4

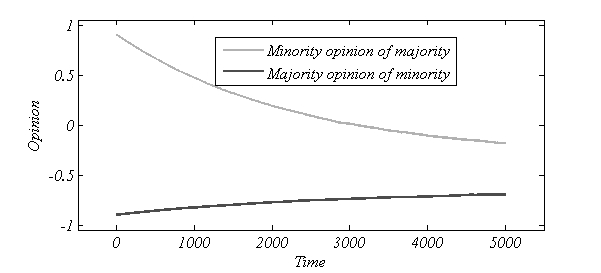

- First, we present the results for the simulations with a minority group size of 60, which were fairly typical of the model's behavior. Figure 1 depicts the time course of the average opinions for a single simulation. Here, the opinion of the minority agent rises from -0.9 to about -0.6 over the course of the simulation. Therefore, agents become less stigmatized over the course of the simulation, making DSIM a model of destigmatization. To examine whether this effect is statistically reliable, we computed the mean stigma from the 40 simulations, and compared the degree of stigma at the beginning with the degree of stigma at the end of the simulations. The t-test revealed a significant effect, t(39)=13.83, p < 0.01, for destigmatization.

Figure 1. Average opinions of the two groups on each other over the course of the simulation - 3.5

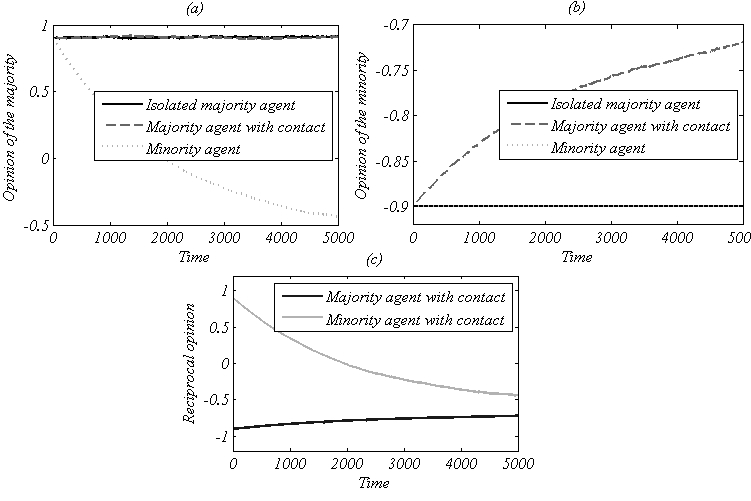

- To explore why this happens with the community of agents, it is important to understand what happens to individual agents. Therefore, we present the exemplary time courses of the opinions of two majority agents, an "isolated majority" agent and a "contact majority" agent, and a minority agent (see Fig. 2). The "contact majority" agent was adjacent to the minority agent. The "isolated majority" agent had no contact with the minority group. As shown in Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b, the "isolated majority" agent did not change its opinions of the minority group; it also did not change its opinions of the majority in any substantial way. While its opinions fluctuated slightly, they remained around 0.90, which is where they were initialized. Similarly, the "contact majority" agent did not substantially change its opinions of the majority groups. Likewise, the minority agent did not change its opinions of the minority group, as it had no other minority group agent to interact with. Finally and importantly, the "contact majority" agent and the minority agent both change their opinions of each other's groups, converging towards each other's opinions. These patterns can be easily explained by examining the "Quality of Interaction" rule:

- 3.6

- If two agents whom are interacting have the same opinion of each other then this rule simplifies to:

Quality of Interaction = Shared Opinion + random(-1,1) (4) This means that the quality of interaction has an equal probability of being greater than, or less than the existing opinion. Thus, while the opinion will change in most cycles, changes are equally likely to be positive or negative, so over many cycles these random changes will cancel each other out leading to largely unchanged opinions. In contrast, for agents with different opinions of each other, the rule turns to:

Quality of Interaction = Average Opinion + random(-1,1) (5) In this case, the agent with the 'above average' opinion is more likely to decrease its opinion, while the agent with the 'below average' opinion is more likely to increase its. Over many interactions, the agent's opinions will converge until they are equal, and the stable state described above is reached.

Figure 2. Six exemplary time courses of the opinions of three agents: an isolated majority group agent, a majority group agent with contact to a minority group agent and a minority group agent without contact to a minority agent but contact with a majority agent. Plot (a) shows the opinion towards the majority group of the respective agents. Plot (b) shows the opinions towards the minority group of the respective agents. Plot (c) directly compares the two opinions of two agents towards each other when they have contact with each other. - 3.7

- However, it is not completely obvious why the 'contact majority' and the minority agents converged towards a point that was closer to the majority agent's negative opinion rather than the exact average of their opinions (See Fig. 2c). To unpack this, it is necessary to remember that in each cycle the 'minority' agent interacts with the 'majority' eight times (once with each majority agent), whereas each 'majority' agent interacts with a 'minority' agent only once. Thus, the 'minority' agent decreases its opinion eight times more quickly, and as such the opinions converge more towards the negative end of the spectrum. This asymmetrical finding is consistent with the meta-analysis results reported by Pettigrew and Tropp (2006).

- 3.8

- The temporal pattern of the individual opinions was observed in the overall simulation (See Fig. 1). However, unlike the individual level results, in which the 'contact majority' and 'minority' group agents would have eventually had the same opinions of one another, the opinions of the 'majority' and 'minority' group agents as a whole will never be equal. This is in part due to the influence of the 'isolated majority' agents who do not have contact with the 'minority' agents, and so never change their (initial) negative opinions. This effect demonstrates that in the DSIM intergroup contact is a necessary perquisite to stigmatization reduction, and so it simulates a crucial aspect of Allport's 'contact hypothesis'.

- 3.9

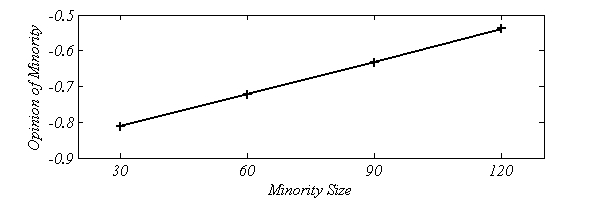

- In the following section, we turn attention to analyzing the effect of minority group size on the final level of stigma of the minority group agents. Consistent with the intergroup and stereotyping literature (Queller and Smith 2002), Figure 3 shows that the majority group's opinion of the minority group depends on the population size. The depicted opinions are averaged across the opinions following the end of ten simulations. We find that for all population variants, minority group agents are less stigmatized by the end of the simulations. Interestingly, it also shows that larger groups (populations) undergo more destigmatization than smaller ones do. (See Fig. 3.)

Figure 3. Relationship between the minority size and the final stigmatization of that minority Discussion

- 3.10

- The simulation results confirm that the behavior of the model is consistent with Allport's contact hypothesis; that is, that intergroup contact leads to a reduction in intergroup bias and destigmatizes the minority group members. We found that only majority group agents who had contact with the minority group improve their opinions of the stigmatized group agents. But, as the majority agents increase their contact with the minority group agents (as varied by group size), there was a decrease in the stigmatization of the minority agents (see also McIntyre, Paolini and Hewstone 2010). The simulations also reveal that, for destigmatization to occur in DSIM, it is essential that the minority group agents start out with 'good opinions' of the majority group agents. If the minority group agents reciprocate the negative opinion of the majority group agents, destigmatization does not occur (and so the agents remain stigmatized). The influence of initial opinions is the by-product of the SFP-based interactions between agents. The fact that the SFP-approach can lead to destigmatisation is surprising, and constitutes an important outcome of the current study. We will turn to a more detailed discussion about this result in the general discussion.

Study 2: Level of Stigmatization and Group Perceptions

Study 2: Level of Stigmatization and Group Perceptions

- 4.1

- To further explore the relationship between increases in stigmatization and the population size of the stigmatized group, we conducted a survey-based study. The purpose was to determine the extent to which there were differences in perceptions of stigma attached to social groups; and moreover, whether this was linked to the different groups' population sizes. Here, we look to confirm that the findings of Study 1 can be validated with 'real world' populations.

Method

Participants

- 4.2

- 102 participants were recruited through the University of Birmingham's official portal (http://www.bham.ac.uk ). From the user base of this portal, it is estimated that there were 36 male and 44 female participants with a mean age of 20.8 years.

Survey

- 4.3

- Drawing on Sidanius and Pratto's (1999) stigma hierarchy, a framework for positing that individuals can perceptive social stigma associated with groups based on the population size of the social groupings, participants were asked to rank order a list of 23 social groups. Participants were instructed to assign each group a number between 1 and 23, using each number only once. (See Table 1.) In this context, a lower number indicated a less stigmatized group (e.g., 1), while a higher number indicated a greater degree of perceived stigma (e.g., 2.3).

Administration

- 4.4

- The on-line advertisement contained a link to an on-line survey. The participants were told they would be participating in a study exploring social attitudes, and they were asked to complete the task as described above. All participants were informed that their results would be confidential, and would in no way impact their future relationship with the university. Upon completion they were thanked and debriefed.

Group Size Measure: Calculating Real World Population Sizes

- 4.5

- The population estimates associated with 23 of the social groups existing databases. Of the 23 groups, information for 14 was drawn from the 2001 UK census, UK government statistics were used for a further 5 groups; and, the remaining ones break down as follows: data from cancer research UK (1 group), epilepsy research UK (1 group), Stonewall (1 group), and a United Nations/ UNHCR (1 group). The percentage of UK residents belonging to each social group was derived from the data. The total UK general population estimate was taken from the census data. Population estimates for social groups (as a ratio) were calculated and later used for analysis.

Results

- 4.6

- We calculated a stigmatization rank for each social group, which was the average of the assigned ranks across individuals. In addition, each social group had a population size, expressed as the percentage, representing the percentage that this group forms of the UK population (see Table 1).

Table 1: Survey results Group Average stigmatization Rank Population Size Population Size Source People with cancer 3.96 3.3 Cancer Research UK Victims of crime 5.18 26 www.statistics.gov.uk Women 5.24 51.32 Census Epileptic people 5.62 0.5 Epilepsy Research UK People over 60 years old. 7.87 20.76 Census Jews 8.21 0.52 Census Chinese people 8.61 0.45 Census People of mixed race 9.04 1.31 Census People who are registered as disabled 11.16 17.93 Census Indian people 11.81 2.09 Census Black carribean people 11.82 1.14 Census Gay people 11.94 6 Stonewall Black african people 12.76 0.97 Census Poor people 12.88 9.2 www.statistics.gov.uk Bangladeshi people 13.19 0.56 Census People registered as unemployed 14.30 2.42 Census Pakistani people 15.64 1.44 Census Arabic people 15.92 0.37 Census Refugees 17.49 0.5 UNHCR People serving a jail sentance 17.74 0.14 www.statistics.gov.uk Homeless people 18.12 0.18 www.statistics.gov.uk Muslims 18.16 3.1 Census Immigrants 18.93 10 www.statistics.gov.uk - 4.7

- In order to examine whether group size and level of perceived stigmatization were related, we examined the correlation between the average stigma ranking assigned to each group and the size of that group's total population. The results show an inverse relationship between group size and stigma, r(22) = -.443, p < .05, such that the more stigmatized the group the smaller the group as a total of the UK's population. Given that some data were drawn from advocacy groups, we re-ran a second analysis using only the UK Census data, because these are known to be the most accurate population data. (This reduces the analysis to 14 groups.) Again, we observe a significant negative correlation between perceived stigma and group size, r(13) = -.583, p < .05, meaning that the more opportunities that one has for contact with stigmatized group (based on the larger number of people in the groups), the less stigma appears to be attached to those social groups.

Discussion

- 4.8

- In this study, we sought to examine whether the relationship between level of perceived stigma and the associated size of the sub-population (found in Study 1) occurs in the general population, extending the earlier work of Sidanius and Pratto (1999) and contextualizing in a UK-based population As indicated, smaller populations were linked to greater levels of stigma. While perceived stigma may differ from the actual level of stigma a group experiences, the two are strongly related, so we can be confident that there is a relationship between stigmatization and group size. The DSIM provides an explanation for why this effect occurs. Small populations within the more general population will have fewer chances for intergroup interactions with members of the mainstream, therefore the absence of opportunities for interaction keeps them more isolated, and thereby more stigmatized.

- 4.9

- While the simulation provided the prediction that group size would be related to stigmatization and a reason for it, the assumptions driving it were untested. We did not include factors such as the 'possible isolation' of the stigmatized group, nor did the set-up contain multiple stigmatized groups, thus, it was important to test whether the findings from Study 1 could map onto individuals' perceptions of the stigmatization, and perceived group sizes in order to validate the model. As DSIM's prediction was borne out, we shall proceed to examine causal relationships, and test some of the moderators of intergroup contact that have been discussed in the literature, but that have never been incrementally nor longitudinally tested.

Study 3: A Direct Manipulation of the Amount of contact

Study 3: A Direct Manipulation of the Amount of contact

- 5.1

- In order to study the effects of intergroup contact, it is necessary to manipulate the amount of contact between agents in the DSIM. In Study 1, the increase of the minority group population size lead to an increase of contact between majority group agents with their minority group counterparts. However, this method conflates group size and the amount of intergroup contact. Instead, the spatial grid of DSIM allows for an alternative variation of amount of contact by changing the size of the neighborhood in which agents interact with one another. In the present study, we vary this spatial neighborhood setting, and the number of neighbors an agent interacts, which is analogous to social space. This implementation does not conflate group size or amount of intergroup contact, and also constitutes an institutively plausible operationalization of social contact. This variable will be termed "amount of contact" or "contact" in short. The aim of this study is to test whether this alternative implementation also result in a decrease of stimgatization.

Method

- 5.2

- The size of the minority was fixed at 120 agents. The amount of contact was set to: 0, 2, 8, 16 or 24. Other than this change, the simulations used the same parameter settings as in the previous studies.

Results

- 5.3

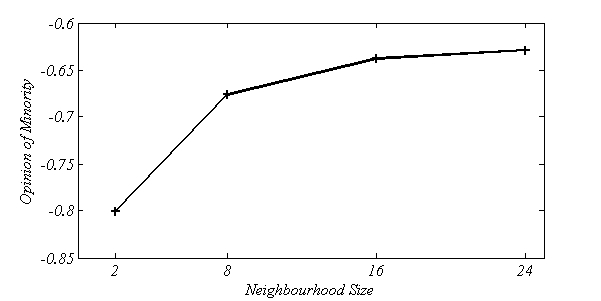

- To explore how neighborhood size functions as a manipulation of intergroup contact, we examined its effects on stigmatization. We compared the amount of contact to the average stigmatization score of the minority agents in each of the simulations. There was a significant correlation between the amount of intergroup contact and final average opinion held by majority agents (of their minority counterparts), r(48) = 0.963, p < 0.001. (See Fig. 4.)

Figure 4. The effect of amount of intergroup contact (neighbourhood size) on final stigmatization score Discussion

- 5.4

- Generally speaking, the results indicated that increasing the size of relative neighborhoods led to a decrease in the stigmatization of the minority group agents. However, it is important to note that as the amount of contact increases, this effect saturates.

- 5.5

- Why does the effectiveness of contact diminish? As we demonstrated in Study 1, majority group agents who are in the neighborhoods of minority group agents improve their opinions (and majority agents and one minority group agent converge to the same opinion). With increasing neighborhood size (and increasing amount of contact), more and more majority group agents come in contact with a minority group agent, and consequently the minority group is less stigmatized. However, at some point 'neighborhoods' start overlapping, so that subsequent increases in contact have little effect. Therefore, simulation results demonstrate that the new manipulation of the amount of contact successfully mimics Allport's (1954) contact hypothesis; but, conversely the simulations also predict that there should be a limitation in the influence of intergroup contact where there is a high level of its occurrence. It is also worth noting that this limitation depends on the density of minority group agents (i.e. the ratio between number of minority group agents and grid size). Lower density, larger neighborhoods can increase to higher level of intergroup before the saturation effect occurs, meaning that density (or perceived space) plays a role in the outcome.

Study 4: Testing Allport's Four Moderators in DSIM

Study 4: Testing Allport's Four Moderators in DSIM

- 6.1

- Thus far, we have focused on the manipulation of the amount of intergroup contact in DSIM, but as we highlighted in the introduction, we also developed implementations of the Allport's four moderators. This study will test whether the implementations of the moderators successfully mimics the empirical findings (see introduction). This test will be conducted in two stages: Stage one establishes whether each individual moderator decreases stigmatization, while stage two examines the interaction between the moderators on intergroup bias in the DSIM. Importantly, this last set of simulations constitutes a test of predictions, as empirical studies have not covered these manipulations, linking them to possible longitudinal measurement (cf. Pettigrew and Tropp 2006).

- 6.2

- In addition, the analysis of the model's behavior is extended, as a result of observations made in Study 1. Study 1 highlighted that not only the final level stigma in DSIM varies, but also the speed at which destigmatization can occur varies. Consequently, we analyze our simulations with respect to these two characteristics. Both sets of analyses have important theoretical implications, which are worth emphasizing. We will show that certain moderators only affect speed of destigmtization, whereas others affect both speed and level of perceived stigma. Empirically, traditional studies of intergroup contact have not been able to disentangle these two effects. One reason is that the 'speed of destigmatization' can only be assessed using longitudinal methodologies, but existing longitudinal studies rarely examine this possibility.

Method

- 6.3

- The impact of the individual moderators was examined in a two-way factorial design. The three moderators, "Common goals", "Cooperation" (Intergroup cooperation), "Authority" (Institutional support) had four levels: 0 (absent), 10 (low), 50 (medium), and 90 (high). The moderator "Status" also had three levels: 20 (low), 40 (medium), and 50 (high). The second factor, neighborhood size, was included with five levels (0, 2, 8, 16, and 32). The size of the minority group was fixed at 120 agents. For each cell, the simulations were repeated ten times, requiring a total of 800 simulations. This design allowed us to examine the manner in which the DSIM behaves across different levels of the moderators. The simulations showed that all moderators, across all levels, had an effect in a similar direction. Therefore only the highest and lowest level of each moderator was used in the interaction analysis. This reduction in levels also simplified the analysis of the results without losing generality.

Results

- 6.4

- There is an observed pattern of destigmatization in all of the simulations, except those in which the 'status' or 'contact' parameters were initialized as zero. In simulations with the zero parameter setting, the majority group agents' final opinion was M= -0.898 (SD = 0.0035), which is not significantly different to its initial setting of -0.90. We further discuss this when we present the analyses of these two parameters, but in general, we shall exclude these results.

- 6.5

- In order to separate speed of destigmatization and the level of final stigmatization, we fitted the following function to each simulation result[2]:

stigmatization = (lambda + 0.9) *((1 - exp(-time*beta)) - 0.9 (6) - 6.6

- This equation is commonly-used to describe natural processes. Lambda describes the point the 'stigmatization' converges towards, while beta tells us how quickly the change occurs. The value "-0.9" takes into account that the destigmatization process begins with -0.9. In the documentation of the simulation results we use the term "final stigmatization" for "lambda" [3]. And, because beta characterizes the speed of change irrespective of the value of lambda, we used "lambda x beta" to measure the speed of destigmatization.

- 6.7

- The influence of each moderator on either speed or final stigma was analyzed with a two-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance), with neighborhood size as a second factor. The interaction analysis was conducted with a regression analysis using z-transformed predictors and criterion. This type of analysis was chosen as it allowed us to gauge the importance of 31 potentially significant interactions between the moderators, thus directing our discussions to important simulation findings.

- 6.8

- This section presents the results from the simulations with the individual moderators, and then the interaction between the moderators. The effects of neighborhood individually are not studied, as the results would be the same as in Study 3. However, interactions with neighborhood are studied to determine whether each moderator influenced the 'contact effect'.

Status

- 6.9

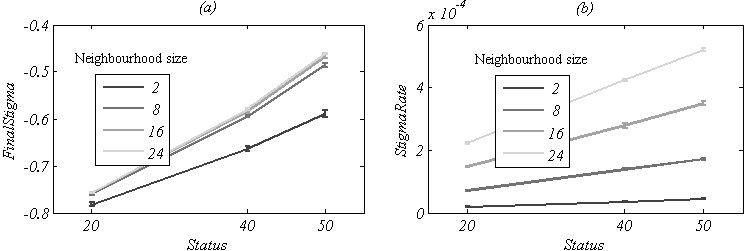

- There was a main effect of status on level of final stigmatization, F(2,108) = 45,106, p < 0.01. We also examined the effect of status on stigmatization, while varying intergroup contact (i.e., different levels of contact). Here, we observed a significant interaction effect, F(6,108) = 367, p < 0.01, indicating that increases in the status of the minority group agents led to lower overall stigmatization scores (see Figure 5a).

- 6.10

- Moreover, there was a significant main effect of status on the 'speed of destigmatization', F(2,108) = 14,953, p < 0.01. Also, there was an interaction effect with 'status' x 'intergroup contact' on 'speed of destigmatization', F(6,108) = 2,160, p < 0.01. The pattern of results indicated that the more equal status which exists between the agents, the quicker the process of destigmatization occurs. Additionally, the magnitude of the effect increased as contact increases, demonstrating that status operates as a moderator of the intergroup contact.

Figure 5. Effects of status on overall levels of stigmatization (a) and destigmatization speed (b) Authority (Institutional support)

- 6.11

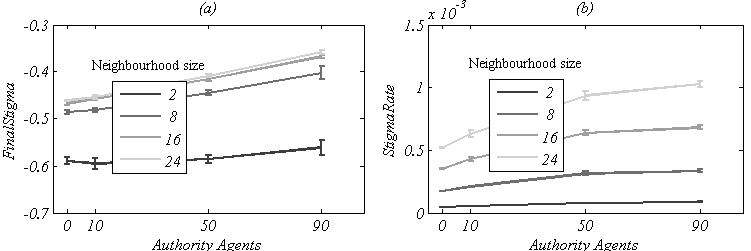

- We tested for direct and moderating effects on level of and the speed of destigmatization on the influence of authority (implemented as authority agents). There were both main effects for 'authority' on the level of stigmatization, F(3,144) = 890, p < 0.01, as well as an interaction effects between authority x contact on the final level of stigmatization, F(9,144) = 41.5, p < 0.01. Increases in sanctioning of contact by authority agents led to lower overall stigmatization for the minority group (See Figure 6a). The effect was larger with more intergroup contact. 'Authority' produced a similar improvement in speed, F(3,144) = 2,352, p < 0.01, which again can be seen to improve with a greater amount of intergroup contact, as the authority x contact interaction shows, F(9,144) = 352, p < 0.01 (Fig. 6b).

- 6.12

- The model shows that 'authority sanctioned' intergroup contact leads to more interactions (per cycle), and in turn, allows destigmatization to take place more quickly. However, this trend did not generalize to decreases in destigmatization that might be felt by the minority agents. Instead, the effect saturates, because an interaction sanctioned by two authority agents is no different to an interaction sanctioned by a single authority agent. In other words, as more authority agents are added, each additional agent becomes less effective, because its influence is more likely to overlap an existing authority agent's influence. Therefore, replacing existing majority agents with authority agents leads to a higher proportion of majority agents being in contact with minority agents, producing an increase in stigmatization in much the same way that group size did in Study 1. As such, the effect of 'authorities' on final stigmatization is spurious.

Figure 6. Effects of Authority Agents on overall levels of stigmatization (a) and on destigmatization speed (b) Cooperation

- 6.13

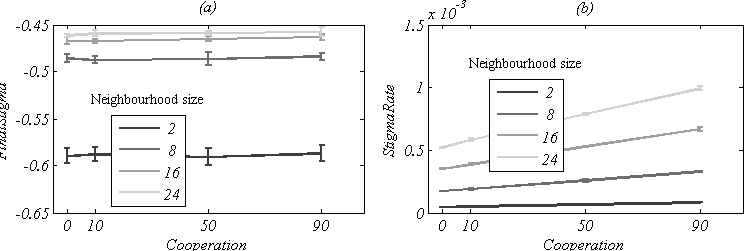

- Cooperation had no significant effect on stigma, F(3,144) = 2.45, p = 0.066, nor was there a significant interaction between cooperation and contact, F(9,144) = 0.41, p = 0.930. However, cooperation did have a significant influence on the speed of destigmatization (F(3,144) = 6772, p < 0.01), and interacted with contact (F(9,144) = 988, p < 0.01). Speed increased with cooperation, and this is even more significant with higher levels of intergroup contact (Fig.7). As existing empirical research has focused on stigmatization using cross sectional methods rather than longitudinal ones, it is possible that this 'increased speed' has been mistaken for an increase in (final) amount of perceived destigmatization.

- 6.14

- The lack of an effect on final stigma can be attributed to the cooperation variable influencing the magnitude of changes in opinion, but without influencing the direction of those changes in opinions. Stigmatization stabilizes, therefore, at the same point it would in the absence of cooperation, but achieving it more quickly through larger changes in agents' opinion at each cycle.

Figure 7. Effects of cooperation on overall levels of stigmatization (a) and on destigmatization speed (b) Common Goals

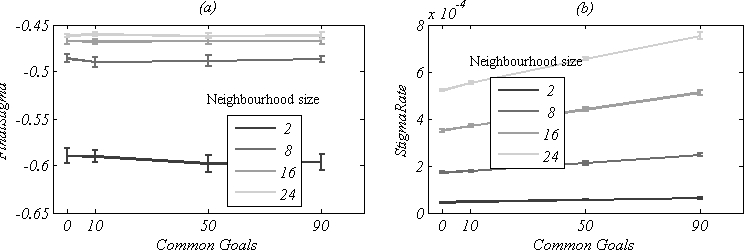

- 6.15

- Common Goals had a very similar effect to cooperation (Fig. 8). Once again, there was no main effect (F(3,144) = 1.85, p = 0.141) or significant interaction with contact (F(9,144) = 1.65, p = 0.106) on stigmatization. However, a main effect (F(3,144) = 2269, p < 0.01) and interaction with 'contact' (F(9,144) = 341, p < 0.01) and 'speed' of destigmatization did emerge. An examination of this relationship told a very similar story to that of the cooperation variable. In this case, however, the explanations in terms of the model were slightly different. As with the authority variable, the common goals variable leads to an increase in the frequency of intergroup interactions, which increases the speed at which destigmatization could occur, but this does not have an effect upon the magnitude of destigmatization.

Figure 8. Effects of Common Interests (Goals) on overall levels of stigmatization (a) and on destigmatization speed (b) Interaction Analysis

- 6.16

- These results show that the DSIM is able to replicate the contact effect (intergroup contact leads to reduction of bias and stigma), and to test the utility of Allport's (1954) "optimal conditions". Our discussion focuses on variables that have been identified as having a significant impact upon final stigmatisation (see Table 2).

The terms with the largest coefficients were 'status', 'contact' and the interaction between 'status' and 'contact'. This is consistent with the individual findings of status on stigmatization. The next largest terms were associated with 'authority' and the interaction between 'contact' and 'authority'. Again, these are positive terms that validate the findings from the individual analysis; however, it is important to remember that the influence of 'authority' results from the placement of authority agents on the grid, rather than their sanctioning of interactions. As such, the effect of 'authority' on stigma does not necessarily simulate the effects of 'authority' as Allport (1954) defined it.Table 2: Regression Analysis of Final Stigmatization (only significant coefficients are listed) Variable Coefficient for stigmatization Authority .162** Contact .350** Status .888** Authority * Contact .084** Authority * Cooperation -.007** Authority * Status .060** Contact * Cooperation .006* Contact * Status .220** Authority * Contact * Status .039** Authority * Cooperation * Status -.006* - 6.17

- The results of the regression analysis on the speed of destigmatization showed that all conditions had an effect (see Table 3).

The regression analysis for 'speed' shows that there were two types of the interaction effects, either positive or very small negative ones. The latter effect always involved 'authority' and 'common goal' variables. In other words, the involvement of both authority agents and common goals does not reinforce destigmatisation (additive effect), as postulated by Allport. The absence of clear interaction results stems from both moderators operating in a very similar way in the model (i.e., both increase the frequency of interactions albeit based on different criteria). In contrast, the other variables affect different mechanisms within the model, thereby reinforcing the effect of each other on destigmatization. For instance, 'cooperation' motivates larger opinion change and 'common goals' leads to a higher frequency change. Consequently, the two variables enforce the speed with which destigmatisation occurs.Table 3: Regression Analysis for Destigmatization Speed Variable Coefficient for Speed Authority .228** Contact .730** Cooperation .251** Common Goals .105** Status .349** Authority * Contact .192** Authority * Cooperation .058** Authority * Common Goals -.005 Authority * Status .091** Contact * Cooperation .212** Contact * Common Goals .088** Contact * Status .293** Cooperation * Common Goals .028** Cooperation * Status .100** Common Goals * Status .041** Authority * Contact * Cooperation .048** Authority * Contact * Common Goals -.007* Authority * Contact * Status .075** Authority * Cn * Common Goals -.002 Authority * Cooperation * Status .021** Authority * Common Goals * Status -.004* Contact * Cooperation * Common Goals .023** Contact * Cooperation * Status .083** Contact * Common Goals * Status .034** Cooperation * Common Goals * Status .010** Authority * Contact * Cooperation * Common Goals -.003 Authority * Contact * Cooperation * Status .017** Authority * Contact * Common Goals * Status -.005 Authority * Cooperation * Common Goals * Status -.002 Contact * Cooperation * Common Goals * Status .008** Authority * Contact * Cooperation * Common Goals * Status -.003 - 6.18

- Finally, the outcome of the interaction analysis is consistent with empirical literature. Allport (1954), emphasized status, Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) predicted a greater role for authorities (though they conceptualize the conditions as functioning together rather than as individual factors), and these are the two most important factors in the model. Of the four optimal conditions, status has the largest effect on both final level of perceived destigmatization and the speed with which this process can occur. If we discount authorities' effect upon stigmatization as an artifact of its implementation, for reasons discussed earlier, it still has a larger effect than the remaining two optimal conditions on speed of destigmatization. In all, we find that, within the DSIM, Allport's (1954) optimal conditions all facilitate the reduction of stigma to some degree, with greater improvements in destigmatization exhibited by conditions previously identified as important, 'status' and 'authority' variables.

General discussion

General discussion

- 7.1

- In this paper, we aimed to tackle a number of important questions surrounding intergroup contact which, if answered, shed light on long-standing issues surrounding intergroup relations. We sought to examine underlying social psychological mechanisms involved in the reduction of bias and stigmatization that might guide interactions between minority and majority group members. The mechanism implemented in this agent-based model draws on the self-fulfilling prophecy theory (SFP) of social interactions. Using this framework, in Study 1 we showed that the minimal model mimics Allport's work on intergroup contact. In addition, the simulations predicted that level of stigma associated with minority groups may be negatively correlated with group size. In Study 2, we confirmed this prediction in a newly constructed survey, thereby validating the model. In Study 3, we extended the DSIM by using the distance at which agents could interact with each other to manipulate the amount of intergroup contact experienced by the agents from the minority and majority groups. Consistent with the 'contact hypothesis' and recent meta-analysis stereotype formation (McIntyre, Paolini and Hewstone 2010), the level of stigmatization of the DSIM's minority group agents decreased with increasing amounts of intergroup contact (see also Queller and Smith 2002). Interestingly, however, this effect saturates. In Study 4, we implement Allport's (1954) four optimal conditions in the DSIM, testing their utility. On the whole, the DSIM successfully replicates the enhanced destigmatization effect of the conditions. However, the results also illustrate a more complex relationship between destigmatization and the optimal conditions, as well as demonstrating complex interactions between these conditions, which impact their overall effectiveness in reducing bias.

- 7.2

- An important finding with our agent-based model is that SFP-based behavior can result in a process of destigmatization. This is counter-intuitive because typically, SFP is assumed to maintain the negative effects of stigma, as the circulate processes in SPF are believed to reaffirm intergroup prejudices (Jussim et al. 2000). Although not consistent with Pettigrew and Tropp (2006), the simulations with the DSIM indicate that it is crucial for stigmatized minority groups to hold a high opinion of the majority group, if destigmatization is to occur. There is empirical support within the intergroup and social identity literature that stigmatized groups can hold positive attitudes towards the majority group if the perceived group permeability, or supports for social mobility, allows the disadvantaged group members to see the majority group status as within their reach (see Ellemers et al. 1988; Ellemers et al. 1993; Verkuyten and Reijerse 2008); thus justifying the starting point. In contrast, if the two groups have a similar evaluation of one another's opinions, then they cannot alter their social position and stigma will remain and hinder future interactions.

- 7.3

- Across the studies, we find that destigmatization only takes place when there is contact between social groups. Consistent with the wider experimental literature, we show that the magnitude of destigmatization increases with the amount of intergroup contact (Study 3). Interestingly, with increasing interactions between groups of agents, the impact of the contact diminishes. This saturation effect can be linked to the way in which 'amount of contact' is implemented in the DSIM. More specifically, the DSIM operationalizes the 'amount of contact' by the size of neighborhoods in which agents interact. Consequently, if the size of the neighborhood is similar in size, or larger than the density of the minority agents, an increase of neighborhood space adds little to the destigmatisation process. Thus, the DSIM would predict that, for high density groupings of minority group agents, the increase of contact will have little impact on the overall destigmatization of the group.

- 7.4

- In the final study, we equipped the DSIM with intuitively plausible operationalizations of Allport's four moderators of intergroup bias. The 'status' of the minority group variable was implemented, as an influence on the relative importance of the minority group's opinion in the social interaction (e.g., the higher the social status, the more the minority group affected the quality of the interaction). In contrast, both the 'common goals' and appeal to 'authority' variables increased the frequency with which individual agents were willing to interact; individual agents who shared common goals, or who were compelled to interaction by authorities they respected tended, both interacted more frequency than agents not exposed to these influences. Finally, 'cooperation' between agents of different social groups enhanced the number of interactions, boosting the amount of opinion change (whether that be positive or negative), that occurred as a result of intergroup contact.

- 7.5

- The simulations results indicate that all moderators strengthen the destigmatization process. Above and beyond this, we note that the moderators differentially influence two characteristics of this process, the speed of destigmatization experienced by a minority group, and the level stigmatization associated with the minority agents' social group. Of the four moderators, 'status' had the largest incremental affect on both properties, facilitating agents to have greater amounts of intergroup contact, thus speeding up the positive effect of these social interactions on the final level of stigmatization. In contrast, the other moderators mainly affect the speed at which a group of minority agents became less stigmatized. As with the 'status' moderator, however, the sanctioning of intergroup contact by an 'authority' decreased stigmatization in the DSIM. There is an important caveat: Outcome was not due to the implementation (i.e., authorities sanctioning interactions), but instead was caused by a secondary effect it. Specifically, authority agents occupy spaces on the grid, changing the ratio of the minority to the majority agents. By implication, these point towards a moderating role for any factor that might influence the ratio of minority to majority members in a given social network (see also McIntyre, Paolini and Hewstone 2010). More importantly, the pattern highlights that increases to interaction quality rather than changing the nature/content will only serve to increase the speed of potential destigmatization, and will not improve the overall quality of the social interactions. We realize that this is somewhat counter-intuitive, but it is not completely inconsistent with the contact research (e.g., Pettigrew and Tropp 2006). It can be mapped onto the literature as follows: one can observe that the quality of interaction is a much greater predictor of positive change over and above that of quantity; and within our context, we argue that quality is a robust predictor of the speed of destigmatization in intergroup interactions.

- 7.6

- Although there is a well-established literature on intergroup contact, it fails to directly test Allport's four moderators of bias/stigma reduction individually, or in conjunction, within the context of a cross-section or longitudinal framework. As such, it has been difficult to determine the relative contributions of these factors, their interactions with one another on intergroup contact over time, or to identify if they might be affecting different properties as they diminish stigma. We sought to redress this gap in the literature by testing the model's general outcome. As such, the current paper tests the unique contribution of each moderator to overall reductions in bias longitudinally; and it opens up new possibilities for identifying properties that result in diminished stigma. The latter has not been traditionally assessed by researchers carrying out empirical studies. They would have typically identify both 'speed' 'final extent of destigmatization' as resulting in diminished stigma, in part one because the common methodologies do not allow for the power needed to tease these two characteristics apart. However, our results strongly indicate that it is worthwhile to carry out such time-consuming, longitudinal studies to gain a better understanding in the effect of contact between social groups.

Limitation and Outlook

Limitation and Outlook

- 8.1

- While this paper has a number of notable strengths, including for the first time, presenting an agent-based model of Allport's (1954) contact hypothesis, we also see limitations in its application. For example, although the experimental and survey research has provided concrete steps towards aiding our understanding of the effects of intergroup contact, there has also been research pointing towards numerous other moderators, e.g. impact of personality factors (Hodson 2008); intergroup anxiety (Turner et al. 2008); imagined intergroup contact (Crisp and Turner 2009), or the knowledge of intergroup contact (Wright et al. 1997). Against this background, it is clear that the DSIM captures a restricted number of factors. Nevertheless, this paper illustrates that an agent-based approach can produces empirically valid results, and in turn, lead to novel theoretically relevant findings. Furthermore, we would argue that agent-based approaches present an ideal tool for future research into intergroup contact, as this framework allows modelers to integrate crucial processes in an intuitive way. For instance, relevant cognitive processes could be integrated into the agents' behavior (imagined contact, knowledge of contact, personality). Likewise, social processes might also be added to the agents' interaction (i.e., communications about extend contacts, social anxiety) allowing for a fully and more integrated understanding of social relations (Abrams 2010; Abrams and Christian 2007). Finally, but without being exhaustive, agents' mobility along with their social characteristics could also be altered to mimic effects of different groups, with differing levels of stigmatization, within geographical or social space. Binder et al. (2009) showed that less prejudiced individuals are more likely to seek contact with stigmatized groups, yet this has not been examined over time so the long-term effects remain unknown. In this context, is also worth mentioning that Binder et al. (2009) touch on another important issue—the causal direction between contact and reduced stigmatization. Here, we also envisage agent-based models to contribute to the debate, as the direction of causation in an ABM is always clear from the implementation of the model, thus making this a powerful tool for exploring debates within the field of intergroup relations.

Appendix A: Definition of Terms

Appendix A: Definition of Terms

-

- Authority (simulation parameter): The number of authority agents present in a given simulation

- Authority agent: An individual designated as an authority, causing nearby intergroup interactions to occur one extra time each cycle.

- Contact (simulation parameter): The range at which an agent can interact with other agents.

- Cooperation (simulation parameter): The degree to which agents cooperate, expressed as the percentage of interactions which are deemed cooperative interactions and double their impact upon opinion change.

- Common Goals (simulation parameter): The frequency with which agents in an interaction will check to see if they share common goals, interacting an additional time that cycle if they do.

- Ingroup agent: Another agent from the same group. For instance, a minority agent interacting with another minority agent would consider the second agent to be an ingroup agent.

- Intergroup interaction: An interaction between a majority and minority agent.

- Majority group: One of the two groups of agents in the simulation. The majority has more members than the minority (the extent of this varies by simulation) and initial opinions of it are positive (0.9)

- Minority group: One of the two groups of agents in the simulation. The minority has fewer members than the majority and initial opinions of it are negative (-0.9)

- Opinion: Agents hold opinions of the social groups

- Outgroup: Another agent from the other group (see ingroup)

- Quality of Interaction: How positive a particular interaction is. This is determined by averaging the involved agents' opinions of each others groups and adding a random number.

- Stigmatisation: The extent to which an individual or group is disadvantaged due to negative views held of it.

- Social Group: A group that an individual, or in the context of the model agent, can belong to.

Appendix B: Full Outcome of Interaction Analysis on Final Stigmatisation

Appendix B: Full Outcome of Interaction Analysis on Final Stigmatisation

-

Variable Coefficient for Lambda Constant .000 Authority (Ay) .162** Contact (Ct) .351** Cooperation (Cn) .003 Common Goals (CG) .001 Status (Ss) .887** Ay * Ct .085** Ay * Cn -.008** Ay * CG .004 Ay * Ss .061** Ct * Cn .005 Ct * CG .002 Ct * Ss .220** Cn * CG .000 Cn * Ss -.001 CG * Ss .003 Ay * Ct * Cn .004 At * Ct * CG -.005 At * Ct * Ss .039** At * Cn * CG -.003 At * Cn * Ss -.007* At * CG * Ss .005 Ct * Cn * CG .000 Ct * Cn * Ss .004 Ct * CG * Ss .000 Cn * CG * Ss -.001 Ay * Ct * Cn * CG -.002 Ay * Ct * Cn * Ss .002 Ay * Ct * CG * Ss -.004 Ay * Cn * CG * Ss -.003 Ct * Cn * CG * Ss .000 Ay * Ct * Cn * CG * Ss .002

Notes

Notes

-

1While we realize that this is inconsistent with Pettigrew and Tropps' evidence, it does allow for social mobility for the stigmatized group, and hence we used the permeability literature to justify our implementation.

2Fitting used MATLABs "fminsearch" function.

3Technically, "final stigmatization" is an inaccurate label, as lambda is never reached; it is the value that stigmatization tends towards as time tends towards infinity. However, as by the end of each simulation stigmatization is very close to lambda, this definition serves for all practical purposes.

References

References

-

ABRAMS, Dominic. 2010. "Processes of prejudice: Theory, evidence and intervention". London:Equality and Human Rights Commission.

ABRAMS, Dominic, and Julie Christian. 2007. "A Relational Analysis of Social Exclusion". In The Mulitprofessional Handbook of Social Exclusion Research, edited by Dominic Abrams, Julie Christian and Dave Gordon, 209-30. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons.

Abrams, Dominic, Julie Christian and David Gordon. 2007. Multidisciplinary Handbook of Social Exclusion Research. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [doi:10.1002/9780470773178]

ALLPORT, Gordon. W. 1954. Nature of prejudice. Cambridge 42, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.

BHAVNANI, R., Miodownik, D. and Choi, H. J. 2011. "Three Two Tango: Territorial Control and Selective Violence in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza." Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(1): 134-158. [doi:10.1177/0022002710383663]

BINDER, Jens, Hanna Zagefka, Rupert Brown, Friedrich Funke, Thomas Kessler, Amelie Mummendy, Annemie Maquil, Stephanie Demoulin, and Jacques-Phillippe Leyens 2009. "Does Contact Reduce Prejudice or Does Prejudice Reduce Contact? A Longitudinal Test of the Contact Hypothesis Among Majority and Minority Groups in Three European Countries." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96 (4): 843-856.

CHRIST, Oliver, Miles Hewstone, Nicole Tausch, Ulrich Wagner, Alberto Voci, Joanne Huges, and Ed Cairnes. 2010. "Direct contact as a moderator of extended contact effects: Cross sectional and longitudinal impact on outgroup attitudes, behavioural intentions, and attitude certainty." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36(12): 1662-1674. [doi:10.1177/0146167210386969]

CHU, Donald, and David Griffey. 1985. "The contact theory of racial integration: The case of sport." Sociology of Sport Journal 2: 323-333.

CLARK, Ronald, Norman B. Anderson, Vernessa R. Clark, and David R. Williams. 1999. "Racism as a Stressor for African Americans." American Psychologist 54 (10): 805-816. [doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805]

CRISP, Richard J., and Rhiannon N. Turner. 2009. "Can Imagined Interactions Produce Positive Perceptions?" American Psychologist 64 (4): 231-240. [doi:10.1037/a0014718]

DESFORGES, Donna M., Charles G. Lord, Marilyn A. Pugh, Tiffiny L. Sia, Nikki C. Scarberry, and Christopher D. Ratcliff. 1997. "Role of group representativeness in the generalization part of the contact hypothesis." Basic and Applied Social Psychology 19 (2): 183-204. [doi:10.1207/s15324834basp1902_3]

ELLEMERS Naomi, Ad van Kippenberg, N. de Vries, and H. Wilke. 1988. " Social identification and permeability of group boundaries." European Journal of Social Psychology 18: 497-513. [doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420180604]

ELLEMERS, Naomi, H. Wilke and Ad van Knippenberg. 1993. " Effects of the legitimacy of low group or individual status on individual and collective status-enhancement strategies." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64: 766-778. [doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.766]

FINKELSTEIN, Joseph, Oleg Lapshin, and Evgeny Wasserman. 2008. "Randomised Study of Different Anti-Stigma Media." Patient Education and Counselling 71: 204-214. [doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.002]

HARRELL, Shelly P. 2000. "A Multidimensional Conceptualization of Racism-Related Stress: Implications for the Well-Being of People of Color." American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70 (1): 42-57. [doi:10.1037/h0087722]

HEGSELMANN, Rainer. and Ulrich Kraus. 2002. "Opinion Dynamics and Bounded Confidence Models, Analysis, and Simulation." Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 5(3): 2. https://www.jasss.org/5/3/2.html

HENRY Adam D., Pawe_ Pra_at, and Cun-Quan Zhang. 2011. "Emergence of segregation in evolving social networks", Proceedings of National Academy of Science 108 (21): 8605-10. [doi:10.1073/pnas.1014486108]

HODSON, Gordon. 2008. "Interracial prison contact: The pros for (socially dominant) cons." British Journal of Social Psychology 47: 325-351. [doi:10.1348/014466607X231109]

IANNACCONE, Laurence R., and Michael D. Makowsky. 2007. "Accidental Atheists? Agent-Based Explanations for the Persistence of Religious Regionalism." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46(1): 1-16 [doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2007.00337.x]

JACKMAN, Mary R., and Marie Crane. 1986. "'Some of my best friends are black...': Interracial friendships and white racial attitudes." Public Opinion Quarterly 50: 459-486. [doi:10.1086/268998]

JUSSIM, Lee. 1986. "Self-fulfilling prophecies: A theoretical and integrative review." Psychological Review 93(4): 429-445. [doi:10.1037/0033-295X.93.4.429]

JUSSIM, Lee, Polly Palumbo, Celina Chatman, Stephanie Madon and Alison Smith. 2000. "Stigma and Self-Fulfilling Prophecies." In The social psychology of stigma, edited by Todd E. Heatherton, Robert E. Kleck, Mcihelle R. Hebl and Jay G. Hull, 374-418. New York, London: The Guilford Press.

KALIK, S. Michael., and Thomas E. Hamilton. 1986. "The Matching Hypothesis Re-examined." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51(4): 673-682. [doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.4.673]

MAJOR, Brenda and Laurie T. O'Brien. 2005. "The Social Psychology of Stigma." Annual Psychology Review 56: 393-421 [doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137]

MCINTYRE , Kylie, Stefania Paolini and Miles Hewston. 2011. "Stereotype Formation and Change through Individual-to-Group Generalization: A Meta-Analytic Review". Working Paper: University of Newcastle.

MIODOWNIK, D. and Cartrite, B. 2010. "Does Political Decentralization Exacerbate or Ameliorate Ethno-political mobilization? A Test of Contesting Propositions." Political Research Quarterly, 63(4): 731-746. [doi:10.1177/1065912909338462]

PARKER, James H. 1968. "The interaction of negroes and whites in an interactive church setting." Social Forces 46 (3): 359-366. [doi:10.2307/2574883]

PETTIGREW, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2006. "A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751-783. [doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751]

QUELLER Sarah, and Eliot R. Smith. 2002. "Subtyping Versus Bookkeeping in Stereotype Learning and Change: Connectionist Simulations and Empirical Findings." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82 (3): 300-13. [doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.300]

SCHELLING, Thomas C. 1971. "Dynamic Models of Segregation." Journal of Mathematical Sociology 1: 143-186. [doi:10.1080/0022250X.1971.9989794]

SIDANIUS, Jim, and Felicia Pratto. 1999. Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. NY: Cambridge University Press

STEELE, Claude M. 1997. "A Threat in the Air. How Stereotypes Shape Intellectual Identity and Performance." American Psychologist 52 (6): 613-629. [doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613]

TURNER, Rhiannon N., Miles Hewstone, Alberto Voci, and Christiana Vonofaku. 2008. "A Test of the Extended Intergroup Contact Hypothesis: The Mediating Role of Intergroup Anxiety, Perceived Ingroup and Outgroup Norms, and the Inclusion of the Outgroup in the Self." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95(4): 843-860. [doi:10.1037/a0011434]

VERKUYTEN, Maykel, and Arjan Reijerse. 2008. "Intergroup structure and identity management among ethnic minority and majority groups: The interactive effects of perceived." European Journal of Social Psychology 38(1): 106-127. [doi:10.1002/ejsp.395]

WILLIAMS, Robin M., Jr. 1947. The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions: A Survey of Research on Problems of Ethnic, Racial, and Religious Group Relations, Bulletin 57, New York: Social Science Research Council.

WRIGHT, Stephen C., Arthur Aron, Tracy McLaughlin-Volpe and Stacy A. Ropp. 1997. "The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 73-90. [doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.73]

WU, Sheng., Li Li, Zunyou Wu, Li-Jung Liang, Haijun Cao, Zhihua Yan, and Jianhua Li. 2008. "A Brief HIV Stigma Reduction Intervention for Service Providers in China." AIDS Patient Care and STDs 22(6): 513-520. [doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0198]