AGENTBLOCKS: A Community Platform for Sharing, Comparing, and Improving Reusable Building Blocks for (Agent-Based) Models

, , , , , , , , , ,

and

aDelft University of Technology, Netherlands; bHelmholtz Centre for Environmental Research - UFZ, Germany; cUniversity of Potsdam, Germany; dTechnische Universität Dresden, Germany; eArizona State University, United States; fCornell University, United States; gThe University of Alabama, United States

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (4) 11

<https://www.jasss.org/28/4/11.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5831

Received: 09-Apr-2025 Accepted: 21-Oct-2025 Published: 31-Oct-2025

Abstract

Agent-based modeling proliferates across applications and scientific disciplines. The downsides of this success are the plurality of code implementations and redundant solutions to recurring modeling tasks. It is especially critical for simulations concerned with modeling human behavior and social institutions. Reusable building blocks (RBBs) are seen as a solution due to their potential to foster standardization grounded in best practices, integration of domain knowledge (including qualitative social sciences) in code, and efficient model design. RBBs are compact code components representing mechanisms or processes useful across models and applications. RBBs have been extensively discussed in the agent-based community, with little progress in implementation. Here, we present an open-access online community platform – AGENTBLOCKS – designed to facilitate the sharing, comparison, review, reuse, and improvement of RBBs. As an international community effort, AGENTBLOCKS leverages lessons from past RBBs discussions and principles from other modeling communities that successfully apply modular, reusable code practices. The paper introduces the interface and structure of this repository, presents templates for RBBs documentation, provides tips to support aspiring users, and first examples. We highlight the need for alternative RBB implementations that share the same generic description. We also acknowledge that RBBs might represent different levels of interactions, starting from decisions concerning a single agent to interactions between multiple agents or agents and their environment. While initially designed to assist agent-based community, the platform can be utilized by other modelers (e.g. system dynamics, integrated assessment, equilibrium) who seek to improve the representation of human behavior, micro-level processes, heterogeneity, interactions, learning, and other complex dynamics. Naturally, the platform is only one element in the chain towards a successful adoption of best software development practices like RBBs. Future work should focus on populating the repository, refining review processes, and systematizing the variety of RBBs’ implementations including engagement with domain experts. Following this initial phase, we hope to further support technical improvements of the platform and widen its impact in and beyond the agent-based community.Introduction

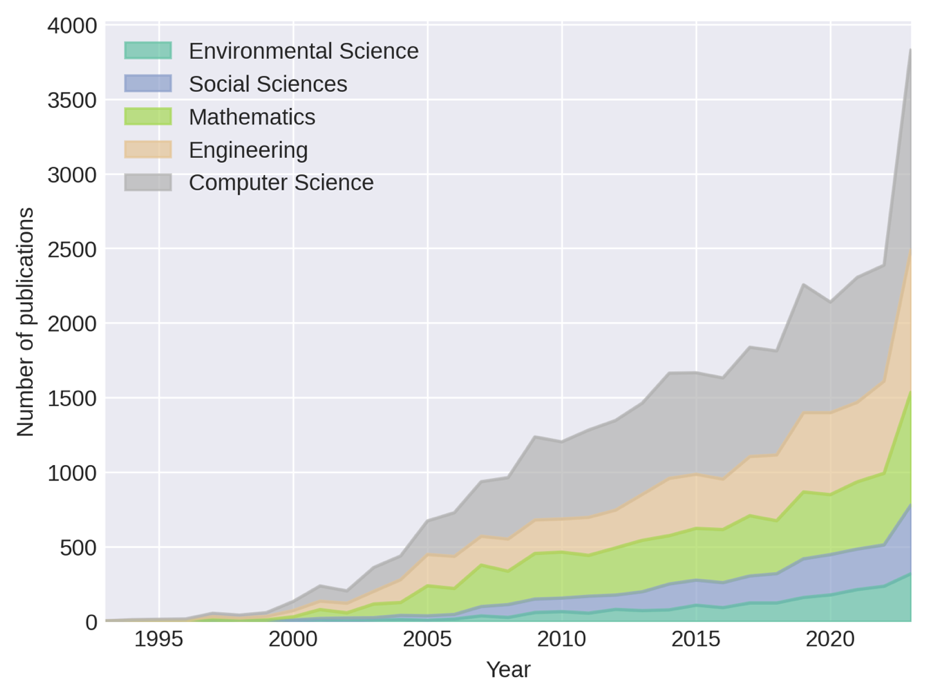

Agent-based modeling has proliferated as a core research method to explore the dynamics of complex adaptive systems (Gilbert 2020). Specifically, agent-based models (ABMs) are on the rise across various domains: the spread of infectious diseases (Lorig et al. 2021), the dynamics of financial markets and evolving economic systems (Tesfatsion & Judd 2006), the emergence of cultural norms (Bianchi & Squazzoni 2015), the behavior of individuals within social networks (Will et al. 2020), transport and urban studies (Heppenstall et al. 2012), rural land use (Rounsevell et al. 2012), ecological dynamics studied in individual-based models (Grimm & Railsback 2005) and responses of coupled social-ecological systems (An 2012; Bousquet & Le Page 2004), energy transition (Chappin et al. 2017; Savin et al. 2023), evacuation (Banerjee et al. 2021; Dawson et al. 2011), adaptation to extreme events like floods, droughts or wildfires also under climate change (Castilla-Rho et al. 2017; Taberna et al. 2020), criminology (Birks et al. 2025), microbiology (Nagarajan et al. 2022) and other life science applications. ABMs effectively capture heterogeneity and interactions among learning adaptive agents who make decisions in changing environments, enabling a ‘generative’ understanding of the underlying mechanisms shaping macro-outcomes that, in turn, affect microprocesses in hierarchical complex systems (Arthur 2021; Balint et al. 2017; Epstein 2012; Filatova et al. 2013; Gallagher et al. 2021). Consequently, this method became widespread across various disciplines (Figure 1).

Yet, this rapidly increasing use of ABMs implies that scholars with different backgrounds – some with strong computational skills but limited domain knowledge or domain experts with limited programming expertise – repeatedly reinvent how to formalize agent behavior in code. The core ABM community promotes rigorous theoretical and empirical foundations (Robinson et al. 2007; Smajgl & Barreteau 2014), thorough sensitivity analyses (Lee et al. 2015; Ligmann-Zielinska et al. 2020; Ligmann-Zielinska & Sun 2010; ten Broeke et al. 2016), calibration (Lamperti et al. 2018), and validation processes (Fagiolo et al. 2007; Smajgl et al. 2011; Troost et al. 2023). ABM developers adopted standardized technical descriptions of models like ODD (Grimm et al. 2020), principles of structured designs of experiments (Lorscheid et al. 2012) as well as workflow protocols (Grimm et al. 2014), and increasingly share code of full models (Janssen et al. 2020). Nonetheless, the recent viral adoption of ABMs (Figure 1) across multiple disciplines, potentially insufficiently familiar with these established ‘good agent-based modeling practices’, has been accompanied by ad-hoc model designs or duplication of similar (sub)models, along with decreased model transparency and reproducibility. This impedes methodological advancements, steepens the learning curve for newcomers, and overall makes ABM development ineffective (Berger et al. 2024).

In addition, in applications where ABMs concern humans, the debate on how to model human behavior remains unresolved (Schlüter et al. 2017; Wijermans et al. 2023). To avoid generating yet another model that is too context-specific (O’Sullivan et al. 2016), models of human behavior should rely on generalizable micro-foundations. Theories from various social sciences conceptualize generic mechanisms of decision-making and change in human behavior and social institutions. Yet, they use qualitative, imprecisely defined narratives that must be formalized in computer code. In bridging this gap, modelers use their own creativity, causing a plurality of implementations of the same theories and types of human decisions, with significant policy implications (Muelder & Filatova 2018). These challenges related to representing human behavior in computational models are not ABM-specific and face similar challenges in integrated assessment modeling (Peng et al. 2021; van Valkengoed et al. 2025). A vetted, well-tested library of reusable models of human behavior and social institutions would provide much-needed clarity and a solid foundation across modeling communities to systematically explore the consequences of alternative representations.

One of the means to address these challenges is to develop shared, peer-reviewed, and transparent reusable building blocks (RBB) (Berger et al. 2024). An RBB encapsulates a component of code – i.e. a small modular part of a complex model – that represents a particular mechanism or process, which repeatedly appears useful across various applications and models and, hence, can be verified and reused. RBBs draw from ideas developed in software engineering (Boehm 1981; Tsui et al. 2022) and integrated environmental modeling (Laniak et al. 2013) to reuse existing software designs and specific code solutions via relatively small code snippets/modules instead of developing complex models from scratch. The advantages of using RBBs are profound and could significantly aid in improving ABM development process and model quality. A modular approach with the core parts of the code peer-reviewed and standardized is time-efficient, less error-prone, transparent, and permits the integration of the domain knowledge in a meaningful way (Box 1). Realizing this mission requires a globally distributed community effort. Berger et al. (2024) suggest a workflow centering around a searchable open-access (OA) online repository where RBBs are submitted, peer-reviewed, assigned a citable reference, and compared to their alternative implementations. Such an online repository is a multi-year international effort supported by forums to discuss progress, and to enable various user communities to address domain-specific and method-focused needs. The goal of this article is to introduce an open access (OA) online RBB repository – www.AGENTBLOCKS.org/ – its core principles, and a brief user guide. While the platform was initiated as the library of ABM components, the RBBs could be useful for other computational modeling communities, including System Dynamics, Computable General Equilibrium or Integrated Assessment Models.

We begin by presenting a brief history of the reusable blocks of code concept in the ABM community, and summarize similar best practices implemented in software engineering and integrated environmental modeling. Subsequently, we introduce the AGENTBLOCKS platform and describe the basic use protocols and elements of the platform, including a step-by-step guide on how to use it, the RBB template, and some examples. The paper concludes with the next steps and future research directions.

Towards Reusable Building Blocks: History and Best Practices

Background

Reusable building blocks in the agent-based community: history, definitions, criteria

The ABM community has been discussing the idea of sharable, reusable code modules for nearly two decades. For example, the development of meta-models and templates for standard tasks in environmental applications aspires to assist newcomers to the field, facilitate their grasp of existing complex models, compare their structure, and design their own new ABMs by borrowing proven ‘conceptual design patterns’, like the ‘Mr Potatohead’ framework for land-use ABMs (Parker et al. 2008). The RBB concept was subsequently promoted in the form of ‘modeling primitives’ (Bell et al. 2015) to support the modeling of socio-environmental systems and in the form of ‘mechanism increments’ (Cottineau et al. 2015) for exploring spatial urban dynamics. To improve the algorithmic representation of human behavior and diverse social institutions in code, Muelder & Filatova (2018) advocated for the development of RBBs to help align computational modeling with social science theories and facilitate dialog between psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and governance and economics scholars who have been studying human decisions for decades.

Recently, Berger et al. (2024) revived this idea, calling for the development of a shared online community library of RBBs, an international online forum to discuss their progress, and a bottom-up global effort. Summarizing lessons from past attempts to establish repositories of reusable modules in non-ABM communities, authors conclude that making RBBs context-independent – reusable as well as plug-and-play components (Börner 2011) – is yet unattainable. Instead, the practical steps should focus on (1) “atomic” RBBs which represent one single mechanism or process rather than modules with multiple or complex functions, and (2) domain-specific RBBs, such as plant competition or buying and selling land for farming, which are applicable across different models. Berger et al. (2024) reviewed RBB drawbacks and barriers, but the advantages (Box 1) outweigh these shortcomings.

We acknowledge that splitting the code of a full model into potentially useful RBBs might not always be straightforward. Hence, it is important to develop a shared understanding of what RBB is and what it is not. Berger et al. (2024) define RBBs as “submodels that represent a particular mechanism or process that is relevant across many ABMs in a certain application domain”. Here, we provide a more detailed definition of RBBs as representing a particular mechanism, process or action by means of standardized, verified, modular small components of a code that can be shared and reused across simulation models within one or more application domains. To build community support for this concept, it is wise to start by developing RBBs for those (agent-based) modeling tasks that are frequently employed across multiple applications and, hence, are relatively standardized already. For example, many social science ABMs have algorithms for some form of social influence or opinion dynamics to simulate agents’ interactions. Yet, many modelers continue creating new, improved algorithms for the same social influence models time after time. Similarly, the increased emphasis on grounding modeling assumptions in empirical data (Lamperti et al. 2018; Robinson et al. 2007; Smajgl et al. 2011; Troost et al. 2023) has necessitated the construction of synthetic populations using micro (survey) data and georeferenced datasets. Despite the emerging attempts to systemize existing methods (Chapuis et al. 2022; Roxburgh et al. 2025), nearly all modelers still start from scratch when coding the initialization of a synthetic population of agents that mimics empirical patterns. Imagine the time saved and the speed at which error-free code could be generated if everyone could access examples previously implemented by others. Having multiple implementations of the same task would allow us to choose the best suited to a specific context, and to identify generalizable features. Even if a specific RBB implementation is coded in a different programming language than a modeler uses, providing an example of a module of interest – along with a flow diagram, pseudocode, and an actual code snippet – facilitates replicating the RBB in different languages.

As RBBs are small code snippets often utilized for tasks that are frequently employed across applications, they can also be easily verified by modelers and scholars from different disciplines. Compared to (10-100s of) thousands of lines of code that typically constitute full complex models, an RBB is a relatively short piece of code accompanied by a description that can be grasped by a human with or without computer science training. Regarding the latter, it might be useful to develop RBBs that relate to expert knowledge and aim to employ rich theory and/or data already developed by a specific discipline. This helps avoid the development of models with ad-hoc assumptions, supports effective inter-/trans-disciplinary collaborations, and simplifies RBB communication by clearly relating its metadata to a known phenomenon/theory.

To summarize, there are four criteria that might help decide whether a specific part of a model code could serve as an RBB. Namely:

- Reuseable: RBBs are elements of the code (representing a certain process, behavior, mechanisms, or a routine algorithm) that are useful for tasks that are frequently employed across applications and models with different purposes.

- Independent: An RBB represents a single mechanism or process within a model. They are connected to other model components through clear inputs and outputs. Therefore, they can be described independently (conceptually and code-wise) – i.e. with limited or no ‘assumption leaks’ – from the rest of the model. If a potentially useful piece of code is so interlinked that it cannot be separated in a meaningful way, then it is not an RBB, or requires re-coding to become one.

- Compact: RBBs are relatively small code snippets, usually ranging from tens to a hundred lines of code, although this depends on the programming language. On the one hand, they represent processes that are more complex than certain simple mechanisms which may be described in, say, a single equation. On the other hand, RBBs that consist of hundreds of lines of code lose transparency, are less useful in a wide array of contexts, and become difficult to communicate, even with a rich metadata description.

- Meaningful: RBBs ideally have a meaning outside the modeling world and can be relatable to domain experts’ knowledge, e.g., link to an empirical phenomenon/pattern/stylized fact or a common theory/law/concept. Having such a generic empirical or theoretical benchmark for an RBB serves as a natural link to domain experts from different disciplines (also non-modelers/non-computer scientists), who can help verify an RBB and its match with their disciplinary knowledge. Alternatively, an RBB could have a technical benchmark, for example, useful for the intercomparison of models with different levels of abstraction (Wimmler et al. 2024) or for supporting repetitive technical tasks, like initialization of a synthetic population with empirical survey data (Roxburgh et al. 2025).

Benefits and added value of reusable building blocks

The advantages of using RBBs are profound (Box 1) and aid in improving and simplifying ABM development. However, despite discussing RBBs for the last 17 years, the ABM community still has not adopted them. Bell et al. (2015) identifies the key challenges, which have been addressed at various modeling venues in 2021-2024 (Volkswagen Foundation, iEMSs, SSC, Santa Fe, CoMSES forum). This led to the path forward (Berger et al. 2024) emphasizing a globally-distributed community efforts to lift it off the ground.

II. Integration of domain knowledge in code: not all modelers are experts in a particular domain, and not all domain experts can code. This can lead to misinterpretations of domain knowledge by programmers or to erroneous coding by non-computer scientists. Compared to large complex ABMs with thousands-lines-long code and have value only for a specific case-study, small snippets of code like RBBs are quicker to verify, easier to communicate between programmers and domain experts, and generalizable across contexts. Having an OA peer-reviewed RBBs repository from engineering, social, environmental and life sciences could facilitate the emergence of shared understanding of real-world processes, facilitating inter/transdisciplinary collaborations.

III. Operationalizing qualitative knowledge in formal code: this point refers mainly to simulating human behavior and social institutions. Many ABMs involve modeling human behavior, but only a small share of published work relates to social sciences (Figure 1), jeopardizing compatibilities between model and social science theories and data. Given the semantic plurality of social science theories and the multi-interpretability of key concepts (e.g. perceptions, awareness, social influence), a catalog of theory-grounded RBBs for key social mechanisms and decisions (possibly based on competing theories), will create a breakthrough and enable collaborative knowledge sharing with non-programming domain experts. Social sciences develop theories that help generalize across contexts and create a shared understanding of studied processes and concepts, like Cobb-Douglas Utility in economics, Self-efficacy in psychology, or Policy Entrepreneur in governance. Yet, the computational modeling community is still to create such a shared set of principles to avoid lengthy explanations of encoded mechanisms. Instead, they could be generalized and referred to as a (set of) RBB.

IV. Efficient model design & code development: ABMs are very powerful, but one of their downsides is the overly time-consuming process of model development. It may take between months to years to conceptualize and code an ABM due to different design and implementation choices. However, many of these choices were already thought through by others, either in the simulation community or by the domain experts. RBBs can increase efficiency of the modeling process. Instead of starting from scratch for every new model, researchers can reuse existing RBBs as a starting point, adapt them to specific contexts, and compare performance of alternative RBBs in different contexts. Having such a time-saving and error-free (verified) option will allow (agent-based) modelers and users to focus on more important stages, like model design and use by stakeholders. It will also assist newcomers to the field with a quick start, freeing the resources to move the field forward by focusing efforts on methodological advancements, innovative and impact-driven research.

One may wonder about the added value of RBBs, given that various modeling communities already openly share codes of their models, e.g. via GitHub. Indeed, for ABMs specifically, CoMSES.Net has created an irreplaceable online resource for sharing OA codes of full models (Janssen et al. 2020). Nearly all newcomers and experts in ABMs use CoMSES.Net and its Forum as the international online hub for discussions. Those who have downloaded a full model at least once might relate that it is incredibly useful to run the full model, play with its settings, and check its code. At the same time, some ABMs have become increasingly complex, with as many as 10-100s of thousands of lines of code. Such massive models are difficult to navigate, especially if one is interested only in a small component of a model, e.g. to learn how another modeler has approached a formalization of a particular decision theory in code and is not interested in a specific context that the rest of the model was designed to represent. For example, one decides to use a Theory of Planned Behavior to model farmers’ cropping decisions and finds an existing OA ABM applying this theory to study e.g. how individuals decide to install solar panels. It takes time to identify the right code element, grasp its implicit assumptions, and trace which inputs/outputs it exchanges with the rest of the model. Sometimes, models no longer function due to outdated or unsupported software, forcing modelers to abandon existing solutions and start reinventing the wheel. An OA RBB repository complements other OA resources like those of CoMSES.Net, with the same RBB potentially being used in several full models stored in the CoMSES.Net library, or one full OA model utilizing several OA RBBs or having several alternative implementations of the same RBB. In such cases, CoMSES.Net and AGENBLOCKS could cross-reference full models and individual code blocks. To build an even stronger bridge between CoMSES.Net and AGENTBLOCKS and avoid the reproduction of the same open-access facilities, we propose to utilize the CoMSES.Net Forum for the discussion of different RBBs.

Best practices of a reusable software design

The ABM community is not the first to discover that standardizing the implementation of frequently used concepts and processes as shareable code elements is a valuable step forward. Software engineering pioneered principles of transparency, efficient code development, and successful reuse of successful software designs and code solutions (Ebert 2018; Krueger 1992; Parnas 1972). Abstraction and modularity are prime concepts in the field of computer science. The goal of software engineering is to help produce reliable, high-quality software that is easy to maintain (Boehm 1981; Tsui et al. 2022). The means to ensure this range from verification techniques such as code testing and static analysis to design methods such as design patterns and model-driven architecture. The latter two are especially relevant in the context of this paper. Furthermore, various environmental modeling communities – including earth system modeling (ESM), surface dynamics modeling (CSDMS), and processed-based climate integrated assessment modeling (IAM) – have been employing the principles of modular software design, which we touch upon here.

Improving coding quality with lessons from software engineering

In software engineering, ‘design patterns’ is a well-established approach that supports code quality, extensibility, maintainability, and reusability. Design patterns are conceptual solutions to common problems in software development inspired by ‘A Pattern Language’ (Alexander et al. 1977), a book on architecture, urban design, and community livability that presented common solutions for recurring problems in the development of homes, streets, and cities (e.g., designing livable family-friendly neighborhoods, walkable business districts, etc.). In software, appropriately selected design patterns generally lead to clean, maintainable, extensible, and performant code by codifying the design and implementation of the software modules needed to solve certain recurring classes of problems. For example, the Command pattern is often used to support undo and redo in text editors, or player actions within a video game (or agent actions within a simulation).

Model-driven software design (MDSD) offers a structured way to develop code, from requirements to conceptual design. Prometheus (Padgham & Winikoff 2002) and MAIA (Ghorbani et al. 2013) provide a template (i.e. pattern) for the conceptual model design. Specifically, MDSD conceptual meta-models – models describing models – vary in degrees of complexity, depending on their abstraction level and intended purpose. At the highest level of abstraction, a Computational Independent Model (CIM) provides a textual or graphical description of the software’s core concepts, independent of any computational language or platform. CIMs are typically used for requirements gathering and domain modeling, ensuring that all stakeholders, including non-technical ones, have a shared understanding of the problem domain. Further, a Platform-Independent Model (PIM) introduces a structured and formalized software representation, still language-agnostic. PIMs, like UML diagrams or pseudo-code, allow illustrating functional specifications irrespective of a programming language. Finally, a Platform-Specific Model (PSM) provides platform-dependent details, such as programming language syntax and software libraries. This stage translates a CIM into an actual code in e.g. Python, NetLogo, or Java. This incremental level of complexity allows experts with different levels of programming expertise to comprehend model concepts and their software implementations.

Embracing design patterns and MDSD as the basis for RBB development offers several advantages. First, it emphasizes the need for compatible modules with clear protocols and a formal description of semantics through ontologies and meta-models. Second, it provides structure and abstraction so that modelers with different levels and types of knowledge can use RBBs at the level that best suits their expertise and needs (e.g. CIM for non-coding domain expert and PSM for programmers). In the long run, an MDSD architecture can also facilitate code automation for plug-and-play simulation components. ABM developers can benefit from semantic alignment checks and tooling, such as model-driven architectures that enable a visual composition of modules and design patterns that offer standardized ways of solving commonly occurring tasks. Leveraging the best practices from modularity in integrated environmental modeling can further facilitate the development of reliable RBBs to be used across domains with diverse environments, requirements, and applications.

Learning from modularity in integrated environmental modeling

The idea of reusing software modules has become a standard practice in environmental modeling (Hutton et al. 2014; Overeem et al. 2013), with CSDMS, OpenMI, and OMF communities establishing principles for successful modular design. Analysis of environmental problems often requires a systems approach that necessitates combining knowledge and simulation models from various domains. Instead of creating large, complex models, the environmental and earth systems modeling community has embraced the practice of integrating domain-specific simulation modules. These modules – simulating soil, watershed, groundwater, or forest-growth dynamics – are science-based components (Laniak et al. 2013). Often, alternative software implementations are developed for the same real-world (sub)system by different teams at different resolutions and scales of analysis. Hence, repeatedly rebuilding the same systems proved inefficient as diverting resources from advancing the field.

Consequently, coupling existing models becomes valuable (Robinson et al. 2018). When implemented in different programming languages, these modules are connected via software wrappers (Belete et al. 2019). For modules to be reusable, several requirements must be met, and some are relevant for RBBs. First, different modules need to be described using standardized documentation that clearly outlines the module’s features. Second, semantic ontology and theoretical assumptions underpinning the design and functionality of each module must be clarified. This is important to avoid unintentionally misusing a component to create ‘integronsters’ (Voinov & Shugart 2013): i.e., two or more integrated models that may technically function as a coupled software product, yet be inconsistent or useless as scientific models. Sharing underlying assumptions and developing a common vocabulary for concepts present in various modules ensures their transparency and interoperable. Third, clear communication of inputs/outputs of each module facilitates effective data flows when a component is used in the bigger model. Lastly, rigorous model intercomparison efforts are due for alternative models capturing the same process, common in e.g. Earth System Modeling and Climate Tipping Point analysis 1.

Notably, environmental modeling deals with physical processes governed by consistent laws of nature. Conversely, ABMs focus on ‘live’ objects that are multi-interpretable. This will have consequences for the development of RBBs. Nevertheless, from integrated environmental modeling ABMs could adopt standardized templates for RBB documentation, clarify RBB inputs and outputs, communicate their theoretical assumptions, and co-develop a community platform for RBB sharing and improvement.

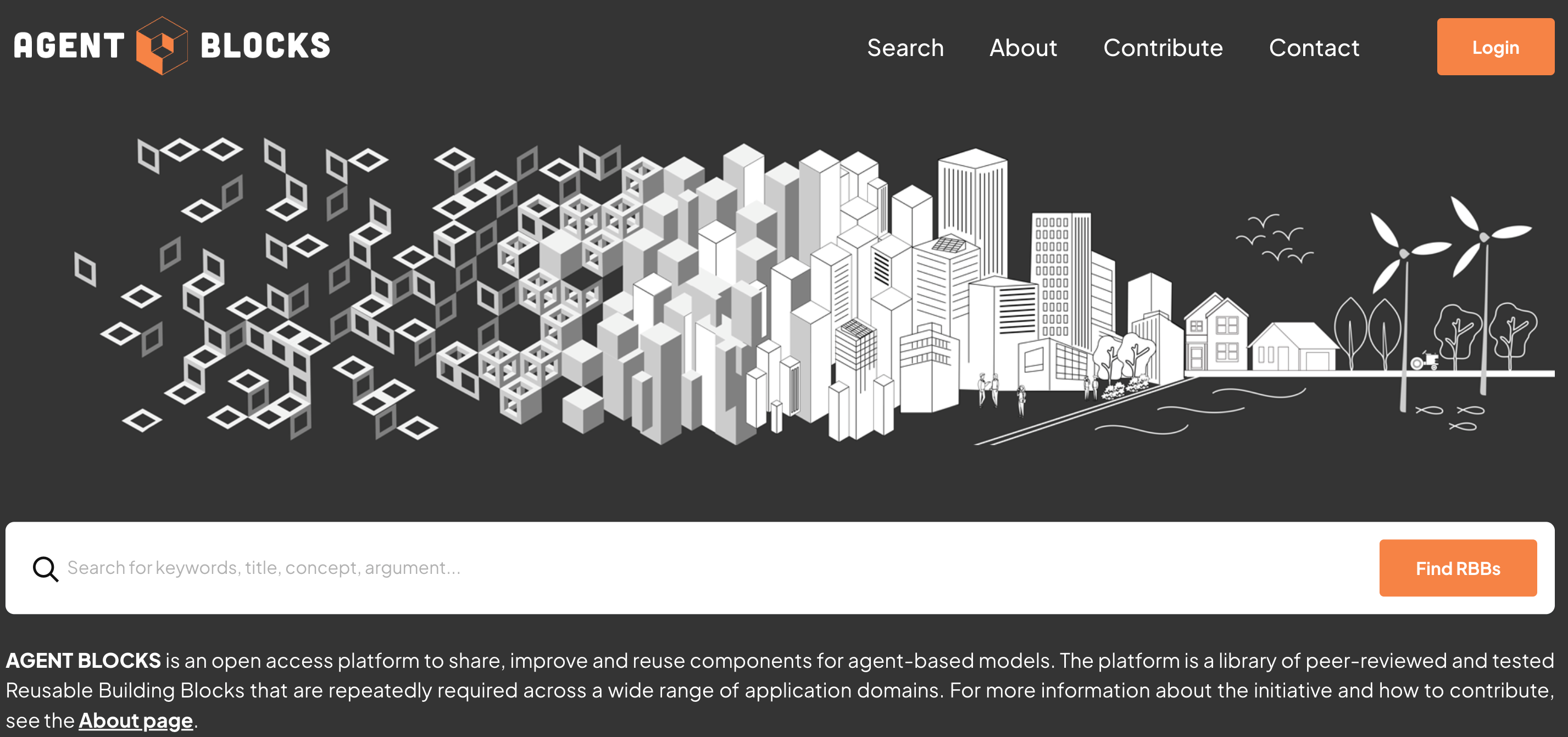

Open Access Community Platform for Sharing Reusable Building Blocks

How it looks

The international OA repository of building blocks for (agent-based) models is hosted at https://www.AGENTBLOCKS.org/. This platform addresses the needs and goals initially outlined by Berger et al. (2024), reflecting the discussion at a series of workshops at the 2021 Volkswagen Foundation, at the iEMSs 2022 Congress, Social Simulation Conferences 2022, 2023, 2024, as well as the Social Simulation Fest 2023 and other modeling community meetings.

The online repository allows academics and practitioners from different disciplines interested in ABMs and related modeling methods to search, upload, review, and revise RBBs meant to represent repeatedly coded processes (Figure 2). AGENTBLOCKS is designed as a living OA web repository of RBBs where domain experts and experienced as well as new-coming (agent-based) modelers can contribute, review, or download RBBs for their own use. It is meant to serve as an interdisciplinary community platform to enable the process of collecting inputs and managing the review and evolution of modules constituting parts of full complex (agent-based) models. These parts can be verified and compared to alternatives, over time leading to the identification of best practices, standardization (e.g. consistent representation of specific processes or behavioral theories in a computer code), and facilitating theory development (e.g. stimulate the refinement of ambiguous constructs and notions, theorize about dynamic feedbacks between concepts, inspire new research questions and empirical measurements; Grimm et al. 2024; Muelder & Filatova 2018).

The AGENTBLOCKS platform is the permanent community platform that replaces the temporary initial solution RBB4ABM (Berger et al. 2024), offering new functions, an updated template (see the Appendix), and the usage process. We foresee the AGENTBLOCKS platform, including the templates, will gradually be adapted, revised, and extended to serve the constantly developing community needs. For example, one of the aspirations would be to advance the platform to host plug & play model components, for example, related to specific application domains (e.g., modeling of technological innovations, ecological forest modeling, climate migration modeling) or a family of alternative modules (e.g., of human behavior modeling) as the next phase of AGENTBLOCKS development.

The AGENTBLOCKS platform grounds in the principles and the template discussed in the ABM community earlier and adapts them further. We argue that unverified unreviewed RBBs with unstructured metadata descriptions will not bring the community closer to the goal. Starting from this, we further develop AGENTBLOCKS accounting for the principles of software engineering and integrated modeling (Table 1).

| Best Practices | Representation in AGENTBLOCKS |

|---|---|

| Learning from software engineering: | |

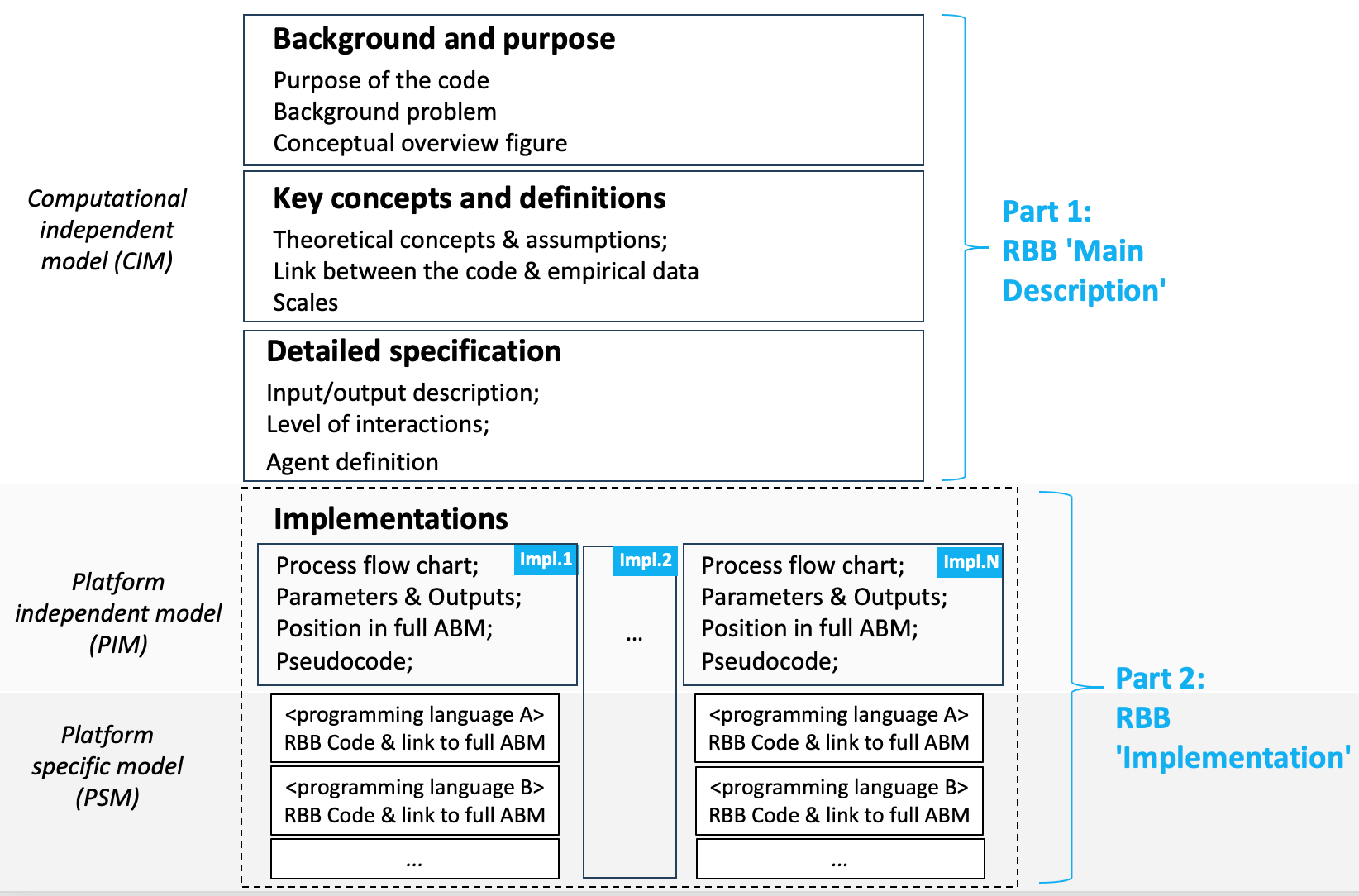

| MDSD differentiates between the generic design of the structure of the code (CIM) and its specific implementation (PIM) coded in a particular software (PSM); | Distinction between the ‘Main Description’ (i.e. Computer independent model in MDSD) and ‘Implementation’ (i.e. Platform independent and platform specific models in MDSD) parts in each RBB, with multiple Implementations possible for the same generic Description (Figure 3); |

| Provision of implementation-specific but platform-independent representation (PIM in MDSD); | Each RBB offers a programming language-independent flow chart and pseudocode (see ‘Implementation’ and Figure 3); |

| In MDSD, the same process can be formalized in multiple ways, and this architecture of the code can in turn be implemented as alternative software versions; | The same generic ‘Main Description’ part of an RBB (i.e. CIM in MDSD) can be coded in different programming languages/software platforms (e.g. Netlogo, Python, Java, C++, etc.). Each code still inherits the ‘parent’ features of CIM and remains comparable to its alternatives (see multiple ‘Implementations’ of an RBB as an example of a PIM and their corresponding code blocks as an example of a PSM); |

| ‘Design patterns’ offer a diagram-based representation of best practices for repeated software elements / tasks; | The essence of an RBB should be visualized via diagrams (e.g. UML diagrams, flow diagrams) to communicate a standard solution to a common task. To reduce the time for creating such diagrams, AGENTBLOCKS offers templates that could be utilized and adapted. |

| Developing a community practice to check existing solutions, e.g. ‘design patterns’, before reinventing a wheel. | Multi-dimensional search function permits users and aspiring modelers to scroll through the database, increasing the chances of improving rather than redoing similar RBBs as the database grows. |

| Learning from integrated modeling: | |

| Clarity on what a code module produces as an output and what inputs it requires to function. | Both the generic ‘Main Description’ and the specific ‘Implementation’ parts of each RBB contain ‘Input description’/‘Input to RBB’ and ‘Output description’/‘Output of RBB’ Sections correspondingly. |

| Clear explanation how a module can be used in a larger complex model. | Each ‘Implementation’ of an RBB contains a diagram indicating the position of a specific RBB in the full ABM. We recommend using a UML sequence diagram (see section ‘Positioning in the Agent-Based Model’ in the example RBBs in Appendix C.1, and Figure A1.c in Appendix A) to explain which processes precede and follow a particular RBB in an exemplar ABM. |

| A code example is complemented with meta-data and ontological clarifications to prevent incorrect code usage & avoid ‘integronsters’. | Each RBB contains ‘lay-scientist’/‘lay-modeler’ explanation about RBB goals and functioning. This applies to both the ‘Main Description’ part of an RBB (see sections ‘Background & purpose’ and ‘Key Concepts and definitions’) and the introductory paragraph of the ‘Implementation’ part. |

Each RBB on the AGENTBLOCKS platform follows the same template (Appendix A). This template clarifies a set of critical elements (Figure 3) that help understand what a specific RBB does and how it functions, in addition to providing the code snippet. Starting from the set of items an RBB template should have (Berger et al. 2024), we have further adapted it by incorporating the best practices (Table 1) and simplifying (distinguishing necessary/optional items). Over time, this template will evolve to better meet community needs and reduce the effort required to complete it.

Before explaining how the platform works, it is useful to highlight that each RBB consists of two parts that carry different functions. The first part – ‘Main Description’ – is a generic description of an RBB independent of a specific implementation (Figure 3, top). It communicates the purpose and the generic structure of an RBB, ideally also to non-modelers. For example, a general description of the Theory of Planned Behavior, frequently used in ABM, its core principles, concepts, and a typical set of inputs/outputs of an RBB representing this type of decision (Appendix C, Example 1).

The second part – ‘Implementation’ – provides a model-specific meta-data description of an RBB and the code of its specific implementation. This part of an RBB provides a detailed discussion of a specific code snippet, its chosen architecture that fits the parent ‘Main Description’ part, the RBB position in the full complex ABM, and the software-independent pseudocode (PIM, Figure 3, bottom). Furthermore, the ‘Implementation’ part contains at least one code snippet in a particular programming language/platform (PSM, Figure 3, bottom). For example, the same RBB grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior can be implemented in Python, NetLogo, or Java. The AGENTBLOCKS platform is designed to accommodate multiple ‘Implementations’ of each ‘Main Description’, which may differ either in the design principles and the underlying architecture or its programming language The former diversity is useful when alternative formalizations of the same process need to be compared; the latter is useful to speed up the diffusion and usage of an RBB across various programming languages/platforms.

Notably, various ‘Implementations’ can co-exist for a single RBB since the same conceptual meta-model (‘Main Description’) can be operationalized differently, even before implementing an RBB in a code. This typically concerns domain-specific alternatives representing the same process. For example, Theory of Planned behavior conceptualizes that subjective norms affect individual decisions, yet there are multiple ways to design how and when they influence the agent’s decision process (Muelder & Filatova 2018). At the same time, reusable code blocks in various programming languages (PSM, Figure 3) are also useful, as ABM developers often prefer a specific language/platform. Besides, AGENTBLOCKS aspires to accommodate this diversity of RBB implementations of the same process (CIM/PIM, Figure 3).

In summary, the ‘Main description’ of any RBB provides a conceptual meta-model (i.e. CIM in MDSD), which can have several ‘Implementations’ (i.e. PIM in MDSD, reproducing a specific flow chart and pseudocode), each containing a reusable code block in a specific programming language (i.e. PSM in MDSD) (Figure 3). The current online version of the AGENTBLOCKS platform denotes these two parts as ‘Main’ and ‘Impl.N [Language]’. Here, all sections of ‘Impl.N’, except the code block itself, indicate a specific, yet programming-language independent, formalization of a particular process described in ‘Main’ and should be understandable by any modeler irrespective of their language/software preferences. The label ‘Language’ refers to the programming language of the published code block, implying that every ‘Implementation’ only contains a single code block in one specific programming language. All implementations of an RBB should reproduce the same conceptualization provided in ‘Main’. As the database grows, one might consider branching the RBB ‘Implementation’ part explicitly into PIM and PSM sections in the next phase of the platform development, so that each ‘Implementation’ can provide multiple code blocks in various programming languages. Importantly, the AGENTBLOCKS platform can host alternative designs, both conceptual and implemented in a specific code, of routinely used elements of ABMs across disciplines and domains.

How it works

The AGENTBLOCKS platform consists of a database of RBBs (see its ontological structure in Appendix B) and an interface to explore, search, contribute and familiarize with them. The landing page offers immediate access to the quick search and several tabs offering the advanced Search function, invitation to Contribute, brief background information, and the Login & Registration page (Figure 2). Each RBB can be characterized by keywords (listed in the ‘Title’, ‘Background & purpose’ and ‘Key concepts and definitions’ fields of Part 1 – ‘Main Description’, see Appendix A), which are searchable. Besides, RBBs can be identified based on the Discipline, the Programming Language, the contributing Author name, and the Level of Interactions. All these fields are defined by the RBB Contributor(s) and serve as search tags in the advanced Search.

AGENTBLOCKS welcomes contributions across 16 disciplines that, to the best of our knowledge, already employ ABM: ranging from ecology to environmental sciences to economics or sociology. If you have not found an RBB fitting your disciplinary interests, it only means that nobody has yet contributed to it 2. You are welcome to have the first say or initialize a domain/discipline-focused group contributing complementary or alternative RBBs. In addition, the administrators of AGENTBLOCKS may assign additional search tags relating to the RBB, its underlying concepts, or its purpose (e.g. currently added search tags to the first RBB contributions are, among others: “decision-making”, “bounded rationality”, “learning”). New search tags can be added to an RBB at any point.

Importantly, ABMs serve as the primary research method to tackle heterogeneity among individual entities (agents), their learning and adaptive behavior, as well as interactions among agents, and between agents and their environment. Therefore, it is wise to differentiate RBBs based on these levels of interactions. In ABMs, all agents, including those representing humans or organisms as well as agents representing environmental processes, need to do something at the agent level: either learn, update, decide, or take an action. Hence, it is intuitive to define the boundaries of what level of interactions, or agent’s sphere of influence, a particular RBB constitutes, and to compare and find RBBs that fit users’ purposes. Specifically, the current version of the AGENTBLOCKS platform differentiates between four Levels of Interactions that an RBB could potentially capture:

- ‘Single Agent’, refers to RBBs coding processes and decisions concerning an individual agent, like a farmer agent making an individual choice of what crops to plant next season, an animal observing its nutrition level, or a rain droplet updating its volume);

- ‘Multiple Agents (same type)’, refers to RBBs that code any form of interactions among two or more agents of the same class, e.g. one bird agent in a flock observing another bird turning, two people influencing each other’s opinions, two traders negotiating, two molecules exchanging energy or substance;

- ‘Multiple Agents (different types)’, refers to RBBs that code any form of interactions among agents belonging to different classes, e.g. an insurance agent selling coverage to different homeowners in flood-prone areas, a wolf eating a sheep, or a soil particle absorbing water;

- ‘Agent(s) and the Environment’, refers to RBBs simulating an agent interacting with its spatial or institutional environment, like a tree agent absorbing soil nutrients within a specific radius, a trader agent reading the aggregate market price, or water droplets freezing in response to the temperature drop.

When the platform is populated, a user can filter out RBBs based on either of the five search dimensions: Keywords, Discipline, Language, Author, and Level of Interactions. On the day of this article publication, AGENTBLOCKS featured eight peer-reviewed examples of RBBs, with 10+ under development. Regarding the level of Interactions, here we provide an example of Single Agent RBBs (e.g. Theory of Planned Behavior, Appendix C, Filatova et al. 2025), the same type Agent-Agent RBB (Degrootian Opinion Dynamics Model of Social Influence, Appendix C, Wagenblast 2024), and the Agent-Environment RBB (Agent expectation formation, Appendix C, Magliocca 2024), with more examples of each type online.

How to start using it

One can explore the platform anonymously or register to contribute and edit RBBs. The AGENTBLOCKS platform foresees several roles: User, Contributor, Reviewer, and Theme Administrator.

As a User (registered or not), one can search among existing RBB examples, read the description of relevant RBBs, copy-paste the code, and adjust it to your own model. To avoid ‘integronsters’ (Voinov & Shugart 2013), a User needs to manually double-check the conceptual fit and inputs/outputs, as RBBs are not plug-and-play model components yet at this stage. Besides directly using an RBB in their own model, Users can discuss existing RBBs (either Part 1 ‘Main Description’ or its alternative formalizations in Part 2 ‘Implementation’) with relevant domain experts, outside the platform, for example, via online Forums (https://forum.comses.net/c/working-groups/reusable-building-blocks/27) or at (self-organized) community events. This can facilitate improvements of existing coding, verify that a specific process is implemented correctly, or differentiate in which context a specific Implementation works best.

As a Contributor (registered), one can decide to either contribute an entirely new RBB or a new alternative Implementation. To keep the repository useful, we strongly encourage Contributors to first check if similar RBBs already exist, for example by employing the advanced search options using multiple keywords, disciplines, etc. To create an RBB, a Contributor is asked to fill in the online form (see the template in Appendix A) for both Part 1 ‘Main Description’ and Part 2 ‘Implementation’. Before starting a new RBB, we strongly advise carefully checking the platform, e.g. using advanced search, to ensure an RBB does not exist yet. If an RBB already exists but you see value in adding an alternative version, for example, because your implementation is structurally different (different PIM), or if you have a working example in a different programming language (different PSM), then just contribute a new Part 2 ‘Implementation’. It is critical that each new alternative implementation is accompanied by an explanation of what makes it different from the original implementation and why (e.g. a better fit to a specific context; validation against data; validation with domain experts; computational efficiency improvement, etc.).

To add a new ‘Implementation’ to an existing RBB, you can request ‘Contributor’s rights’ to an existing RBB by going to the ‘Contribute’ page or clicking the link under ‘Contribute to this RBB’ on any RBB page, then select the tab ‘Add your own implementation to an existing RBB’ and click the link ‘ask us for access directly’, which will automatically generate an email to the AGENTBLOCKS Administrators. In this request, you can specify which RBB you want to add an ‘Implementation’ to and add a short explanation on what makes it different from the existing one. After the Administrator’s approval, you receive the editing rights. To make a new ‘Implementation’ useful, be as explicit about its added value and differences from the existing implementation(s) as possible. For example, describe the different context you developed it for, or clarify that you made changes following the data/expert validation; always explain the improvements (conceptual or computational) you are suggesting, ideally in comparison to one of the previously published versions of the code block. The AGENTBLOCKS mission is to enable alternative versions to co-exist to facilitate both (i) the transparency about which ‘Implementations’ work best in what contexts and, (ii) over time, the evolutionary development of standardized best practices on coding a specific process/concept/theory.

Meanwhile, testing RBB of human or plant/animal decisions in different contexts could lead to improving the conceptual ‘Main Description’, not just the code ‘Implementations’, making RBBs an actionable method for theory development and testing. Notably, a good quality technical description takes time. To speed up the process of developing the RBB metadata, we offer editable templates for diagrams (Appendix A). Naturally, to acknowledge each contribution, the AGENTBLOCKS platform adds a citation for each contribution.

All RBBs submitted to AGENTBLOCKS are peer-reviewed. As a Reviewer (registered), one can judge whether the description of an RBB is sufficiently clear (e.g. no obligatory fields missing, diagrams of the RBB rather than of only full ABM are present, a justification for a new ‘Implementation’ is provided, etc.). It would not serve the community to have duplicates; hence the platform will ask Reviewers to reflect on the RBB novelty (please see the question “Does the RBB describe an original, not yet existing in the database, component of an ABM?” in Appendix D). To minimize the effort, the online platform offers editable forms and a short list of items to reflect on as ‘yes/no’ option. The expectation is that a Reviewer does a visual inspection, i.e., a minimum verification, to see if an RBB’s code snippet implements the RBB’s main description. More complex forms of verification, such as testing or static analysis, are a topic for future work. For now, the responsibility for the quality of the code remains with the Contributor. If a Reviewer has made significant suggestions for improving RBB, the RBB authors might consider inviting him/her as a Contributor (i.e. to be added to the list of authors in the RBB citation).

Lastly, as this OA repository of RBBs grows, in addition to general Administrators at Delft University of Technology, we foresee Theme Administrators3 appearing to help curate and coordinate the content. They could be experts in both ABM and a specific domain (e.g. as Guest Editors for journals). For example, Theme Administrators might suggest relevant Reviewers and judge whether a new ‘Implementation’ helps or hinders the wider community’s progress. Theme Administrators also play a role in the three-tier screening process aimed to avoid duplicates: they check the novelty of each newly submitted RBB, and may revert it back to Contributors with an invitation to resubmit as a new ‘Implementation’ to an existing RBB instead of an entirely new submission.

The AGENTBLOCKS platform grew from the bottom up, driven largely by persistent voluntary efforts of many people, funded through various resources, and benefiting from the extensive feedback at various community events. Given its nature and community-focused aspirations, the platform’s governance structure will remain community-driven, supported internationally by Users, Contributors, and Reviewers, with the RBB submissions and reviews organized bottom-up. Delft University of Technology, as the Host Institute, will continue to manage the submission process and provide technical user support in the near term, while also ensuring the long-term stewardship of the repository. The International Board of Collaborators 4 will continue its oversight and its vital advisory role, serving as the backbone of the platform, including its partnership with CoMSES.Net. This said, the platform fundamentally relies on the ‘distributive governance’ principles, distancing from top-down conflict resolution or moderation of content concerning issues like “which implementation or RBB is better/wins”. Instead, we leave it to the community to govern the content by deciding which RBB/Implementation they want to use and by discussing their choices openly at the Forum of the sister CoMSES.Net. As the platform grows, its governance model will evolve toward an even more distributed structure, with Theme Administrators taking on roles analogous to (guest) editorial boards in academic journals — curating content, fostering community participation, and ensuring standards within their respective domains of expertise. However, to maintain AGENTBLOCKS in the long run, structural funding for maintenance and further development will be essential. Much could be learned here from other OA efforts, like DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, CoMSES.Net, the Open Modeling Foundation (OMF), and CSDMS, and other practical experiences among the research software developers (Skinner et al. 2025).

Discussion & Conclusion

With the rise of ABMs in environmental, socio-economic, and engineering applications, there is an urgent need to improve and simplify the modeling process. One of the means to achieve this is to develop shared, peer-reviewed, and transparent ‘reusable building blocks’ of code – RBBs – that implement a certain behavior or process (Bell et al. 2015; Berger et al. 2024; Cottineau et al. 2015; Muelder & Filatova 2018; Parker et al. 2008). RBBs enable reusing existing software designs and specific code solutions via relatively small code snippets instead of developing complex models from scratch. The advantages of using RBBs are profound as they reduce time for the development of complex models, diminish conceptual and coding errors, create transparent means to discuss code implementations of specific processes and concepts (e.g. human behavior in formal models) with domain experts. This article introduces www.AGENTBLOCKS.org/: an OA RBB platform to search, submit, review, assign a citable reference to an RBB, and compare their alternative implementations.

Parsing out the assumptions we make as modelers and sharing them on a common, atomized footing puts us in a better position to meet the demands of new models and new modelers; and in a better position to characterize (through intercomparison) the consequences of these assumptions when embedded in models. Importantly, building out an infrastructure of reusable (and reused) blocks for the current and next generation of modelers will help inform questions around the criticality of ‘reinventing each wheel’ as part of the training process as modelers, and what new frontiers become possible when all the wheels are already available for us. The community-driven OA AGENTBLOCKS platform aims to facilitate this process. As with any community effort, the introduction of the (online) repository to share knowledge is just a starting point in a wider chain of the complex process. To uncover the power of RBBs for the progress in complex systems modeling – ABM and beyond – we foresee the following next steps.

Community events: it is up to us all to share knowledge and discuss it with each other in a friendly manner. Any repository is as useful as the quality and variety of resources it offers. We hope agent-based modelers will be interested in sharing their wisdom in the form of RBBs, gradually populating the platform. As with anything new, there is a learning process. Hence, focused workshops and training sessions on the AGENTBLOCKS platform and conference sessions dedicated to sharing RBBs are a natural way to simplify this process, with several international workshops already held between 2021-20255. Furthermore, international groups of modelers working on specific topics – e.g. ecological modeling, land use modeling, technological modeling, climate-economy interactions – could contribute topic-oriented families of RBBs and their alternative implementations. This will also help structure the existing knowledge from various modeling groups working on similar issues, encourage domain-specific best practices for ABM development, and empower newcomers. One such example is an ongoing effort to collect different representations of human behavior in land-use models (Kunkel et al. 2025). Furthermore, the modeling community might benefit from developing structured educational resources, learning from the pathways offered by Software & Data Carpentries and The Turing Way6 open-access initiatives. Lastly, as with other contributions and review activities, these academic services need to receive explicit recognition. Ideally, domain experts and interdisciplinary teams see value in sharing their best practices by contributing at least one RBB. Such efforts can be shared in an accompanying paper. Hence, an RBB can create co-benefits: offer an OA RBB that is possibly used and cited a lot, and a publication that also can have higher impact than ordinary research papers. These benefits are of particular importance for early career researchers, especially when recognition and rewards in academia are shifting, putting more weight on Open Science. Moreover, the ABM community might put this public service in the spotlight by means of the ‘Best Reviewer’ and ‘Best RBB’ awards via venues like CoMSES, JASSS, and other relevant journals and conferences.

Systematize the variety of implementations: the variety of RBBs in the database should ideally evolve, improve, and mature to a systematized, possibly standardized way of implementing specific tasks. Initially, it would be useful to collect several code implementations of the same RBB. Yet, it is critical to keep track of how they perform in different contexts, which one is more computationally efficient, and which fits better the original real-world process it aspires to model. For example, conceptually different classes of opinion dynamics models (Acemoglu & Ozdaglar 2011; Flache et al. 2017) – e.g. De Groot, Bounded Confidence, or Bayesian – will likely each be coded as distinct RBBs. Further, since in practice different modelers may produce alternative code versions even of the same conceptual model, e.g. De Groot opinion dynamics model (Wagenblast 2024), the AGENTBLOCKS platform enables publishing multiple implementations of the same RBB. Our expectation is that – through testing in diverse contexts and engagement with domain experts, like social scientists studying opinion dynamics in practice – the computational modeling community will gradually converge toward the best validated code implementation(s). In this evolutionary process, weaker performing or overly complex versions of the same RBB are abandoned, while robust ones are reused and refined. The outcome may be a single widely accepted implementation of a specific RBB or its context-dependent variants: e.g. opinion dynamics diffusion of pro-environmental practices versus spread of misinformation, or reputational opinion dynamics among schoolchildren versus diffusion of opinions among industrial farmers about crop performance. These best standardized RBBs might need to be coded differently, even for the same De Groot model. However, coding of other less context-dependent processes, for example in ecology (e.g. ‘Dynamic Energy Budget theory for animals’; Grimm et al. 2025), might be refined over time to converge to the single best standardized RBB, with context captured by specific parameter values. Such community wisdom could evolve supported by discussions via the CoMSES Forum and at domain- and method-focused conferences. In addition, interdisciplinary dialogues between modelers and domain experts without computer science/modeling experience could be very instrumental for the ontological verification of RBBs. For example, one could think of a workshop between psychologists, sociologists, behavioral economists studying human behavior, and agent-based modelers. Such dialogs could focus on how well qualitative concepts are being formalized in a computer code for RBBs like ‘Theory of Planned Behavior’ (Filatova et al. 2025) or ‘Protection Motivation Theory’ (Verbeek & Filatova 2025) and alike, related to human behavior representation in models, and what can be improved.

Technical improvements of the platform: during this first phase, the community might need a few years to try the RBB concepts, and create topical libraries for different disciplines (ecology, geography, governance, or management sciences) and application domains (transport or disease diffusion) to simplify the template further or add new dimensions that are critical. As new needs emerge, revisions of the platforms will be due in a few years. The next structural advancement could be to develop a library of plug-and-play components to truly leverage the best principles of the modular development of complex models. Besides, the advancement of Large Language Models (LLMs) opens new opportunities for speeding up coding and modeling practices in general, as well as RBBs’ efforts in particular. We are at the dawn of a new era in modeling, with LLMs mimicking stakeholders, AI-agents proposing full-fledged conceptual causal-loop diagrams for specific problems, and co-piloting and independently writing computer code (Vanhée et al. 2025). The AGENTBLOCKS platform can benefit from these complementarities offered by LLMs, especially for rote technical tasks. For example, the power of LLMs can be used to automate screening for RBB duplicates, to translate an RBB coded in one language to another, to answer questions and synthesize information about RBBs (like CoMSES Librarian7), to make suggestions for its improvement (aligned with e.g. FAIR4RS principles; Barker et al. (2022)) or to generate an RBB’s metadata description, especially for templatized rubrics. At the same time, what a human-designed/reviewed RBB offers is irreplaceable by LLMs: with a good prompt, it is relatively easy to get some Python code for e.g., theory X or process Y. Yet, it requires experience and a broader understanding of the ontology of the issue at hand to ensure that, e.g., ‘utility’, ‘preference’, ‘energy exchange’ or ‘growth function’ in one RBB is used in the right context in the code in relation to other factors/variables in the same RBB/function, or that these concepts mean the same as they do in another part of the model code to which this RBB connects. Though powerful, LLMs still require a human to check their quality (verification, ensuring scientific rigor and ethics), fit for specific circumstances (context, curation of data, validation), the cohesion with theoretical foundations (to avoid hallucinated, nonsensical, or contradictory assumptions), consistency, diligence, and research direction (including designing novel model architectures aligned with specific empirical evidence or new theoretical hypothesis). LLMs amplify human abilities to design and code models, but responsibility for the quality remains ours. All of these future stages of the AGENTBLOCKS platform advancement will require funding. Financing such community research infrastructure is possible, as has been demonstrated by IAM and ESM communities.

Impact beyond the agent-based community: The AGENTBLOCKS has started as an ABM community effort. However, such RBBs can, of course, be used for other types of models – System Dynamics, Computable General Equilibrium, or IAM – that aim to improve a representation of micro-level processes, heterogeneity, interactions, out-of-equilibrium dynamics, and learning and adaptive behavior in their code. For example, global climate-economy IAMs have been criticized for decades for missing these critical functionalities, especially when it concerns representing human behavior and social institutions in those models (Peng et al. 2021; van Valkengoed et al. 2025). They could benefit from the multi-decadal experience of agent-based modelers, and use the peer-reviewed RBBs in their code.

By fostering a culture of sharing and open code development, interdisciplinary knowledge exchange, and continuous improvement, AGENTBLOCKS aspires to transform the way complex (agent-based) models are built by making high-quality, reusable code accessible to everyone. As more people start participating, the potential for collective wisdom and knowledge advancement spanning siloed disciplinary boundaries grows exponentially. As the international community continues refining such shared OA resources, their impact on advancing computational methods and knowledge will grow.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the participants of multiple community events at international conferences and workshops for their feedback and suggestions. These events include the Volkswagen Foundation workshop 2019, the iEMSs conference 2022, the SocSim FesT 2021, the SSC conferences 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025. We are thankful for the support from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (grant agreement no. 758014) for funding the core costs for the platform development. Authors are also thankful to the 4TU.DeSIRE Program of the four Dutch Technical Universities and the Multi-Actor Systems Department of TU Delft for co-funding the costs for the platform development. We thank ElementSix, for their continuous support with the software side of the platform development. Lastly, the authors are thankful to the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions.

Notes

Appendix

The appendix can be found at the following link: https://www.jasss.org/28/4/11/Appendix.pdf

References

Acemoglu, D., & Ozdaglar, A. (2011). Opinion dynamics and learning in social networks. Dynamic Games and Applications, 1(1), 3–49. [doi:10.1007/s13235-010-0004-1]

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I., & Angel. (1977). A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford University Press.

An, L. (2012). Modeling human decisions in coupled human and natural systems: Review of agent-based models. Ecological Modelling, 229, 25–36. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.07.010]

Arthur, W. B. (2021). Foundations of complexity economics. Nature Reviews Physics, 3(2), 136–145.

Balint, T., Lamperti, F., Mandel, A., Napoletano, M., Roventini, A., & Sapio, A. (2017). Complexity and the economics of climate change: A survey and a look forward. Ecological Economics, 138, 252–265. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.03.032]

Banerjee, I., Warnier, M., Brazier, F. M. T., & Helbing, D. (2021). Introducing participatory fairness in emergency communication can support self-organization for survival. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 7209. [doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86635-y]

Barker, M., Chue Hong, N. P., Katz, D. S., Lamprecht, A.-L., Martinez-Ortiz, C., Psomopoulos, F., Harrow, J., Castro, L. J., Gruenpeter, M., Martinez, P. A., & Honeyman, T. (2022). Introducing the FAIR principles for research software. Scientific Data, 9(1), 622. [doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01710-x]

Belete, G. F., Voinov, A., Arto, I., Dhavala, K., Bulavskaya, T., Niamir, L., Moghayer, S., & Filatova, T. (2019). Exploring low-carbon futures: A web service approach to linking diverse climate-energy-economy models. Energies, 12(15), 2880. [doi:10.3390/en12152880]

Bell, A. R., Robinson, D. T., Malik, A., & Dewal, S. (2015). Modular ABM development for improved dissemination and training. Environmental Modelling & Software, 73, 189–200. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2015.07.016]

Berger, U., Bell, A., Barton, C. M., Chappin, E., Dreßler, G., Filatova, T., Fronville, T., Lee, A., Van Loon, E., Lorscheid, I., Meyer, M., Müller, B., Piou, C., Radchuk, V., Roxburgh, N., Schüler, L., Troost, C., Wijermans, N., Williams, T. G., & Grimm, V. (2024). Towards reusable building blocks for agent-based modelling and theory development. Environmental Modelling & Software, 175, 106003. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2024.106003]

Bianchi, F., & Squazzoni, F. (2015). Agent‐based models in sociology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 7(4), 284–306. [doi:10.1002/wics.1356]

Birks, D., Groff, E. R., & Malleson, N. (2025). Agent-based modeling in criminology. Annual Review of Criminology, 8, 75–95. [doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-022222-033905]

Boehm, B. W. (1981). Software Engineering Economics. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Börner, K. (2011). Plug-and-play macroscopes. Communications of the ACM, 54(3), 60–69. [doi:10.1145/1897852.1897871]

Bousquet, F., & Le Page, C. (2004). Multi-agent simulations and ecosystem management: A review. Ecological Modelling, 176(3–4), 313–332. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2004.01.011]

Castilla-Rho, J. C., Rojas, R., Andersen, M. S., Holley, C., & Mariethoz, G. (2017). Social tipping points in global groundwater management. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(9), 640–649. [doi:10.1038/s41562-017-0181-7]

Chappin, E. J. L., de Vries, L. J., Richstein, J. C., Bhagwat, P., Iychettira, K., & Khan, S. (2017). Simulating climate and energy policy with agent-based modelling: The Energy Modelling Laboratory (EMLab). Environmental Modelling & Software, 96, 421–431. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2017.07.009]

Chapuis, K., Taillandier, P., & Drogoul, A. (2022). Generation of synthetic populations in social simulations: A review of methods and practices. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 25(2), 6. [doi:10.18564/jasss.4762]

Cottineau, C., Reuillon, R., Chapron, P., Rey-Coyrehourcq, S., & Pumain, D. (2015). A modular modelling framework for hypotheses testing in the simulation of urbanisation. Systems, 3(4), 348–377. [doi:10.3390/systems3040348]

Dawson, R. J., Peppe, R., & Wang, M. (2011). An agent-based model for risk-based flood incident management. Natural Hazards, 59(1), 167–189. [doi:10.1007/s11069-011-9745-4]

Ebert, C. (2018). 50 years of software engineering: Progress and perils. IEEE Software, 05. [doi:10.1109/ms.2018.3571228]

Epstein, J. M. (2012). Generative Social Science: Studies in Agent-Based Computational Modeling. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [doi:10.23943/princeton/9780691158884.003.0003]

Fagiolo, G., Moneta, A., & Windrum, P. (2007). A critical guide to empirical validation of agent-based models in economics: Methodologies, procedures, and open problems. Computational Economics, 30(3), 195–226. [doi:10.1007/s10614-007-9104-4]

Filatova, T., Verbeek, L., & Schwarz, L. (2025). Theory of planned behavior for individual decision-making (version 1.0). AGENTBLOCKS Library of Reusable Building Blocks for Agent-Based Models. Available at: https://www.agentblocks.org/rbb/theory-of-planned-behavior-for-individual-decision-making/release/1.2 [doi:10.2139/ssrn.5219387]

Filatova, T., Verburg, P. H., Parker, D. C., & Stannard, C. A. (2013). Spatial agent-based models for socio-ecological systems: Challenges and prospects. Environmental Modelling & Software, 45, 1–7. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.03.017]

Flache, A., Mäs, M., Feliciani, T., Chattoe-Brown, E., Deffuant, G., Huet, S., & Lorenz, J. (2017). Models of social influence: Towards the next frontiers. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 20(4), 2. [doi:10.18564/jasss.3521]

Gallagher, C. A., Chudzinska, M., Larsen-Gray, A., Pollock, C. J., Sells, S. N., White, P. J. C., & Berger, U. (2021). From theory to practice in pattern-oriented modelling: Identifying and using empirical patterns in predictive models. Biological Reviews, 96(5), 1868–1888. [doi:10.1111/brv.12729]

Ghorbani, A., Bots, P., Dignum, V., & Dijkema, G. (2013). MAIA: A framework for developing agent-based social simulations. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 16(2), 9. [doi:10.18564/jasss.2166]

Gilbert, N. (2020). Agent-Based Models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Grimm, V., Augusiak, J., Focks, A., Frank, B. M., Gabsi, F., Johnston, A. S. A., Liu, C., Martin, B. T., Meli, M., Radchuk, V., Thorbek, P., & Railsback, S. F. (2014). Towards better modelling and decision support: Documenting model development, testing, and analysis using TRACE. Ecological Modelling, 280, 129–139. [doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.01.018]

Grimm, V., Berger, U., Meyer, M., & Lorscheid, I. (2024). Theory for and from agent-based modelling: Insights from a virtual special issue and a vision. Environmental Modelling & Software, 178, 106088. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2024.106088]

Grimm, V., Martin, B. T., & Jager, T. (2025). Dynamic energy budget (DEB) theory for animals (version 1.2) [Computer software]. AGENTBLOCKS Library of Reusable Building Blocks for Agent-Based Models. Available at: https://www.agentblocks.org/rbb/dynamic-energy-budget-theory-for-animals

Grimm, V., & Railsback, S. F. (2005). Individual-Based Modeling and Ecology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Grimm, V., Railsback, S. F., Vincenot, C. E., Berger, U., Gallagher, C., DeAngelis, D. L., Edmonds, B., Ge, J., Giske, J., Groeneveld, J., Johnston, A. S. A., Milles, A., Nabe-Nielsen, J., Polhill, J. G., Radchuk, V., Rohwäder, M.-S., Stillman, R. A., Thiele, J. C., & Ayllón, D. (2020). The ODD protocol for describing agent-based and other simulation models: A second update to improve clarity, replication, and structural realism. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 23(2), 7. [doi:10.18564/jasss.4259]

Heppenstall, A. J., Crooks, A. T., See, L. M., & Batty, M. (Eds.). (2012). Agent-Based Models of Geographical Systems. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

Hutton, E. W. H., Piper, M. D., Peckham, S. D., Overeem, I., Kettner, A. J., & Syvitski, J. P. M. (2014). Building sustainable software - The CSDMS Approach. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1407.4106.

Janssen, M. A., Pritchard, C., & Lee, A. (2020). On code sharing and model documentation of published individual and agent-based models. Environmental Modelling & Software, 134, 104873. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2020.104873]

Krueger, C. W. (1992). Software reuse. ACM Computing Surveys, 24(2), 131–183. [doi:10.1145/130844.130856]

Kunkel, J., Grimm, V., Müller, B., Jurak, K. A., Groeneveld, J., Polhill, G., Roxburgh, N., Meyer, M., Huber, R., Hotz, R., Schwarz, L., Berger, U., Stindt, C., Grothmann, L., Zeng, Y., Verbeek, L., & Filatova, T. (2025). Reusable building blocks of decision models. In preparation.

Lamperti, F., Roventini, A., & Sani, A. (2018). Agent-based model calibration using machine learning surrogates. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 90, 366–389. [doi:10.1016/j.jedc.2018.03.011]

Laniak, G. F., Olchin, G., Goodall, J., Voinov, A., Hill, M., Glynn, P., Whelan, G., Geller, G., Quinn, N., Blind, M., Peckham, S., Reaney, S., Gaber, N., Kennedy, R., & Hughes, A. (2013). Integrated environmental modeling: A vision and roadmap for the future. Environmental Modelling & Software, 39, 3–23. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.09.006]

Lee, J.-S., Filatova, T., Ligmann-Zielinska, A., Hassani-Mahmooei, B., Stonedahl, F., Lorscheid, I., Voinov, A., Polhill, G., Sun, Z., & Parker, D. C. (2015). The complexities of agent-based modeling output analysis. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 18(4), 4. [doi:10.18564/jasss.2897]

Ligmann-Zielinska, A., Siebers, P.-O., Magliocca, N., Parker, D. C., Grimm, V., Du, J., Cenek, M., Radchuk, V., Arbab, N. N., Li, S., Berger, U., Paudel, R., Robinson, D. T., Jankowski, P., An, L., & Ye, X. (2020). ‘One size does not fit all’: A roadmap of purpose-driven mixed-method pathways for sensitivity analysis of agent-based models. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 23(1), 6. [doi:10.18564/jasss.4201]

Ligmann-Zielinska, A., & Sun, L. (2010). Applying time-dependent variance-based global sensitivity analysis to represent the dynamics of an agent-based model of land use change. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 24(12), 1829–1850. [doi:10.1080/13658816.2010.490533]

Lorig, F., Johansson, E., & Davidsson, P. (2021). Agent-based social simulation of the Covid-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 24(3), 5. [doi:10.18564/jasss.4601]

Lorscheid, I., Heine, B.-O., & Meyer, M. (2012). Opening the “black box” of simulations: Increased transparency and effective communication through the systematic design of experiments. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 18(1), 22–62. [doi:10.1007/s10588-011-9097-3]

Magliocca, N. (2024). Agent expectation formation (version 1.0). AGENTBLOCKS Library of Reusable Building Blocks for Agent-Based Models. Available at: https://www.agentblocks.org/rbb/agent-expectation-formation

Muelder, H., & Filatova, T. (2018). One theory - many formalizations: Testing different code implementations of the theory of planned behaviour in energy agent-based models. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 21(4), 5. [doi:10.18564/jasss.3855]

Nagarajan, K., Ni, C., & Lu, T. (2022). Agent-based modeling of microbial communities. ACS Synthetic Biology, 11(11), 3564–3574. [doi:10.1021/acssynbio.2c00411]

O’Sullivan, D., Evans, T., Manson, S., Metcalf, S., Ligmann-Zielinska, A., & Bone, C. (2016). Strategic directions for agent-based modeling: Avoiding the YAAWN syndrome. Journal of Land Use Science, 11(2), 177–187. [doi:10.1080/1747423x.2015.1030463]

Overeem, I., Berlin, M. M., & Syvitski, J. P. M. (2013). Strategies for integrated modeling: The community surface dynamics modeling system example. Environmental Modelling & Software, 39, 314–321. [doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.01.012]

Padgham, L., & Winikoff, M. (2002). Prometheus: A methodology for developing intelligent agents. Proceedings of the First International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems: Part 1. [doi:10.1145/544743.544749]

Parker, D. C., Brown, D. G., Polhill, J. G., Deadman, P. J., & Manson, S. M. (2008). Illustrating a new “conceptual design pattern” for agent-based models of land use via five case studies - The MR POTATOHEAD framework. In A. López Paredes & C. Hernández Iglesias (Eds.), Agent Based Modeling in Natural Resource Management (p. 39).

Parnas, D. L. (1972). On the criteria to be used in decomposing systems into modules. Communications of the ACM, 15(12), 1053–1058. [doi:10.1145/361598.361623]

Peng, W., Iyer, G., Bosetti, V., Chaturvedi, V., Edmonds, J., Fawcett, A. A., Hallegatte, S., Victor, D. G., Vuuren, D. van, & Weyant, J. (2021). Climate policy models need to get real about people - Here’s how. Nature, 594(7862), 174–176. [doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01500-2]