Agent-Based Modeling as an Evaluation Tool to Understand the Mechanisms of a Financial Incentives Scheme for Maternal and Child Health in Tanzania

,

,

,

,

,

,

and

aKuwait University, Kuwait; bDasman Diabetes Institute, Kuwait; cIfakara Health Institute, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; dLondon School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom; eUniversity of Bern, Switzerland; fThe Bartlett School of Environment, Energy and Resources, University College London, United Kingdom; gInternational Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (4) 7

<https://www.jasss.org/28/4/7.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5793

Received: 13-Aug-2024 Accepted: 02-Sep-2025 Published: 31-Oct-2025

Abstract

Agent-based models (ABMs) offer a robust mechanism for modeling dynamic health systems and their responses to reforms, capturing vital feedback loops between agents, and incorporating agent heterogeneities. We constructed an ABM to investigate the effects of a supply-side payment-for-performance (P4P) scheme for childbirth care in Tanzania, specifically focusing on its impact on demand-side behaviours. Three classes of agents were included in the model: women of reproductive age, healthcare providers (facilities), and a district manager. For women, we incorporated a key decision-behavior with respect to the location of the birth: opting for the nearest facility or home. On the providers' end, responses to bonus incentives were modeled, considering aspects such as staff kindness and the levying of out-of-pocket informal charges. The model demonstrated that supply-side improvements could occur due to (i) changes in provider behavior driven by financial incentives, (ii) alterations in facility characteristics resulting from received incentive payments, and (iii) district manager facilitation of resource and strategy sharing. In particular, the model captured the potential limits of improvement on the supply side as demand increases, representing the added demand pressure on the system. The agent's decision about delivery site is influenced by (i) her previous experience with home and facility delivery, (ii) experiences shared by peers, and (iii) advice from traditional birth attendants. Agent characteristics were derived from impact evaluation data, a multilevel mixed-effect logistic backward stepwise regression analysis, and unmeasured influences captured through literature and stakeholder input, all contributing to the model's authenticity. The model, developed in AnyLogic, estimates that the current implementation of P4P, including bonus payment delays, led to a 21.5% increase (+15.4 percentage points) in facility-based deliveries compared to a counterfactual without P4P. Furthermore, avoiding payment delays observed during implementation could result in a further increase of 4.7% (+4.1 percentage points) in facility-based deliveries. The model explored variations in facility responses to P4P, finding that initial facility performance indicators, along with the size of the population of the catchment and the capacity ratios of the facility, are key factors that enabled facilities with lower initial performance and smaller catchment areas to perform better. Programmatic steps to avoid payment delays (and the associated increases in 'out-of-pocket' informal charges during delays) should be prioritized. Through the model, we have demonstrated how program evaluation data can inform the development of an ABM, which can elucidate the pathways to impact and program bottlenecks by virtually reconstructing agents and observing emergent system-level behaviours. Our framework has generalizable methodological steps for others seeking to use ABM to better understand how health system strengthening programs such as P4P affect the behavior of providers and patients.Introduction

Payment for performance (P4P), or financial rewards to healthcare entities, contingent on their achievement of predefined performance targets, is gaining popularity as a mechanism to improve health service delivery. The assumption underpinning P4P is that health providers will respond to incentives by increasing effort, with additional funds motivating performance, thus resulting in improved health outcomes (Miller & Babiarz 2014). In the context of maternal healthcare, predefined performance targets typically include metrics such as the percentage of institutional deliveries, antenatal care coverage, and immunization rates. The ‘principal-agent problem’ arises when health providers (agents) may not always act in the best interests of policy makers, health system managers, or patients (principal), especially when incentives are not aligned (Smith et al. 1997). By overcoming the principal-agent problem, theory suggests that P4P should improve the desired behavior of the health provider, resulting in better health outcomes (Paul et al. 2021).

P4P has been widely implemented worldwide and, in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), there has often been a focus within these settings on maternal and child health (MCH) (Diaconu et al. 2021; Witter et al. 2012). Much of the initial evidence in these settings focused on evaluating the impact of P4P on MCH outcomes, with mixed conclusions (Witter et al. 2012). Subsequently, the research focused on exploring the health system mechanisms through which P4P improves outcomes (Diaconu et al. 2021; Renmans et al. 2016; Singh et al. 2021; Witter et al. 2012), reporting improvements in the availability of health workers and drugs (Diaconu et al. 2021), community outreach, patient trust and facility autonomy, and reductions in patient care costs (Singh et al. 2021). Furthermore, the context within which P4P programs are implemented appears to matter, with differences in effects noted depending on the characteristics of the facility and the community (Singh et al. 2021), with a recognized need for more research that explicitly studies this (Binyaruka et al. 2020; Diaconu et al. 2021). P4P design is also known to influence program mechanisms and outcomes (Diaconu et al. 2021; Kovacs et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2021), but design effects can be challenging to examine empirically, as program design is typically homogeneous within a country (Kovacs et al. 2020). An aspect of program design is the role of local authority health managers in P4P schemes. When involved in verification visits, this can strengthen the governance function of the health system and offer an avenue to support providers, especially when they are also incentivized (Singh et al. 2021).

Existing empirical evaluations of P4P and other complex health systems policies are often constrained by factors including their assessment of effects ex-post, limited statistical power that may limit the ability to detect effects or conduct subgroup analysis to explore the heterogeneity of effects, and the lack of data for counterfactual scenarios. Such limitations can significantly hinder the ability to uncover the heterogeneity in the initial conditions and the resulting trajectories. The pressing need to improve MCH outcomes in LMIC and the growth of P4P programs in the region, make a compelling case for additional in-depth evaluations of system-level dynamics and community outcomes. To overcome these limitations, computational systems science tools, such as agent-based modeling, have been proposed as an approach to better understand the functioning of health systems and assess the dynamic effects of health system interventions such as P4P.

Agent-based models (ABMs) are increasingly used as a mathematical modeling method to capture the micro-level behavior of complex systems such as health systems (Alibrahim & Wu 2020; Borghi & Chalabi 2017; Macal & North 2005). The modeling approach simulates agents embedded with decision-making capabilities, progression trajectories, and the interaction within and between agent types (Badham et al. 2018). ABMs have been used to model health systems and their dynamic response to various incentive-based reforms, capture feedback loops between agents and incorporate heterogeneities in the emergent behavioral response to reforms (Alibrahim & Wu 2018, 2020; Cassidy et al. 2019; Shrime et al. 2019). ABM can create virtual replicas of social systems, enabling exploration of the interaction between different program design components and individual agent decision-making, informing more effective program design.

This study conceptualizes, develops, and validates an ABM to recreate and understand the drivers of P4P in institutional deliveries using empirical data from the woman, community, and facility level in Tanzania. The developed model is built as a policy and evaluation tool to disentangle the effects of the unique characteristics of the P4P design over a 3-year study period. Specifically, the model aims to recreate empirical trajectories through a simulated representation of individuals within this setting of care. The model is conceptualized, parameterised, calibrated, and verified using empirical data, published literature, and stakeholder interviews. Empirical data used in the model include household surveys, facility surveys, and program reports. Key endline outcomes, such as the proportion of births in a facility, the patient experiences of facility-based deliveries, and access to drugs, are used for validation. The model was developed to shed light on counterfactual scenarios and help decision makers refine the design of the Tanzanian P4P program for MCH. In the following sections, we explain the conceptual framework for the ABM, methods, results, and conclusions.

Study Setting

Tanzanian maternal and child health system

The MCH care system and the delivery of services need to be strengthened in Tanzania (UNICEF 2024). The availability of drugs and supplies remains challenging, and the referral and transport systems are inadequate. Limited access to insurance schemes and informal payments in health facilities pose financial barriers to access. The achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1, 3, 5, and 10 depends on the increasing coverage and quality of MCH services in low-income settings (UNDP 2024). In this study, we focus solely on primary care facilities that play a pivotal role in MCH.

Pwani P4P program design

This model focuses on the Pwani Region, one of Tanzania’s 31 administrative regions located along the eastern coast. In this setting, predefined performance targets included specific percentage increases in institutional deliveries and antenatal care visits. The design of the P4P program has been described elsewhere (Binyaruka et al. 2015; Borghi et al. 2013), but a summary follows. The program was implemented in facilities with a bank account, offering MCH services and providing baseline performance data from previous years. Facilities were eligible for incentive payments for deliveries if they met targets for each 6-month cycle: a percentage point increase in performance compared to the previous cycle or an absolute performance target. For primary healthcare facilities (dispensaries and health centers), 75% of this payment was distributed among health workers at the facility and the remaining funds were to be spent on improvements to the facility (25%). Managers at the district and regional levels who were responsible for supporting facilities and verifying facility performance data, the Council Health Management Team (CHMT), the Regional Health Management Team (RHMT), and the district were also eligible for incentives.

In each six-month performance cycle, the performance metrics reported by a participating facility were compared to target performance to determine bonus eligibility. In this analysis, we focus on the number of births in the facility calculated as the percentage of total births in the catchment area of the facility. The target performance value for each indicator is calculated based on a threshold-specific target detailed in section 3.10. If the facility met or exceeded the indicator’s target, it received the full bonus. If the facility met at least 75% of the target performance, it received 50% of the bonus. All achievements below the 75% threshold do not receive incentive payment (Binyaruka et al. 2015). The maximum payout per cycle was US$820 for facility (Binyaruka et al. 2015). If a facility receives the maximum payout, the portion allocated to health workers amounts to approximately 10% of an individual staff member’s salary, when distributed across the average number of staff at a facility.

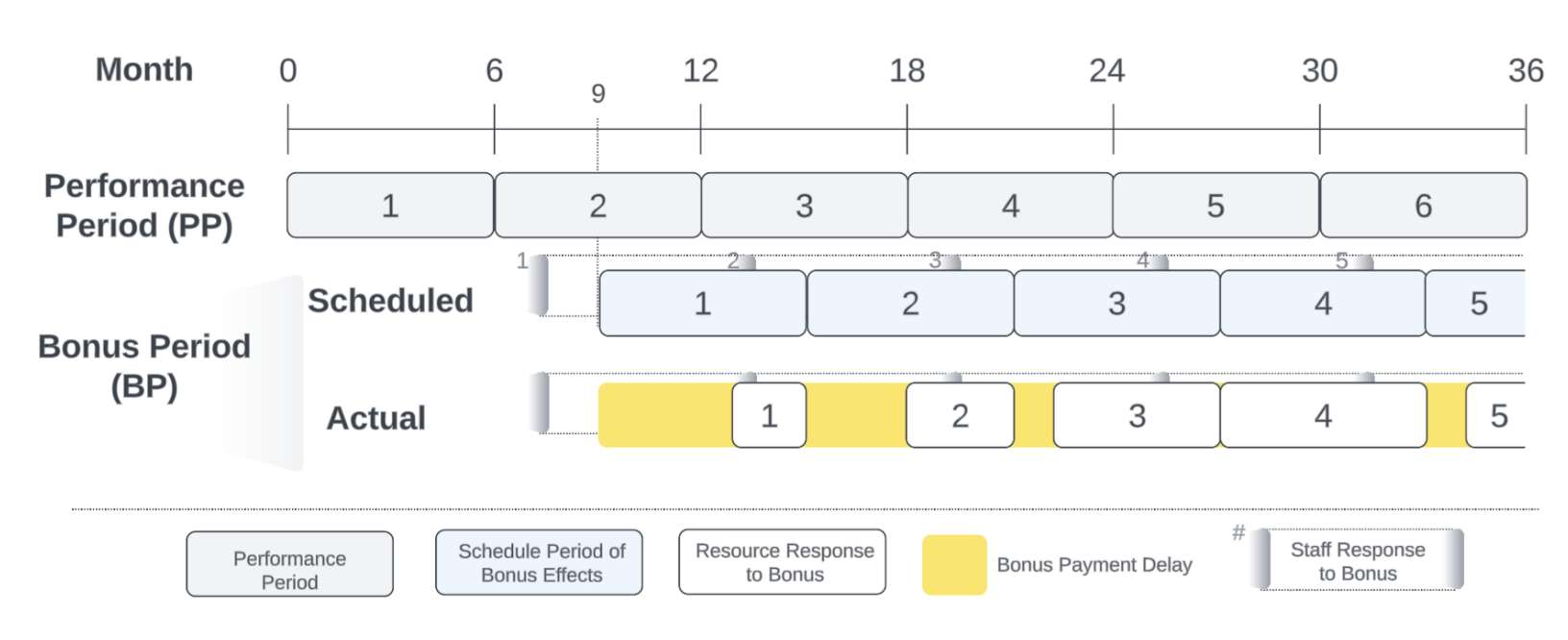

Facilities regularly reported performance indicators to the Council Health Management Teams. District health managers then verified performance during routine facility visits (every three months) to ensure accurate, complete, and consistent data. District health managers were incentivized based on the performance of the facilities in their areas, the availability of drugs, and the timely submission of performance reports. It was expected that each payment verification cycle would take 2-3 months. The intention was that all facilities receive the P4P incentive payment at most three months after the end of the previous cycle. However, payment delays were common, and the first bonus payment was processed three months later than originally scheduled. Table 1 shows the actual and scheduled bonus payment timelines. Evident delays in bonus payment processing led to challenges in maintaining drug supplies, staff motivation, and outreach activities. Table 1 presents the timeline of performance cycles and bonus payments in the Pwani P4P program, highlighting the critical issue of payment delays that forms a key focus of our research. While all facilities in the study were part of the P4P program, the timing of bonus payments varied significantly from the scheduled dates, allowing us to examine how payment timeliness affects outcomes. Therefore, we focus on delays within the Pwani P4P program as a potential policy lever in the ABM to understand how reductions in delays might improve the rate of in-facility deliveries.

| Cycle | Start | End | Scheduled Payment | Actual Payment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jan 2011 | Jun 2011 | Sep 2011 | Jan 2012 |

| 2 | Jul 2011 | Dec 2011 | Mar 2012 | Jun 2012 |

| 3 | Jan 2012 | Jun 2012 | Sep 2012 | Oct 2012 |

| 4 | Jul 2012 | Dec 2012 | Mar 2013 | Mar 2013 |

| 5 | Jan 2013 | Jun 2013 | Sep 2013 | Oct 2013 |

| 6 | Jul 2013 | Dec 2013 | Mar 2014 | Jun 2014 |

Methods

The agent-based model

Our agent-based model simulates the complex interactions between three key agent types within the maternal healthcare system in Tanzania: women of reproductive age, healthcare facilities, and district managers. The model explicitly incorporates both supply-side dynamics (facility responses to incentives) and demand-side behaviours (women’s healthcare-seeking decisions). These exogenous demand-side dynamics, including demographic factors, social influences, and previous experiences, play a crucial role in determining outcomes and are modeled based on empirical data from household surveys and stakeholder input.

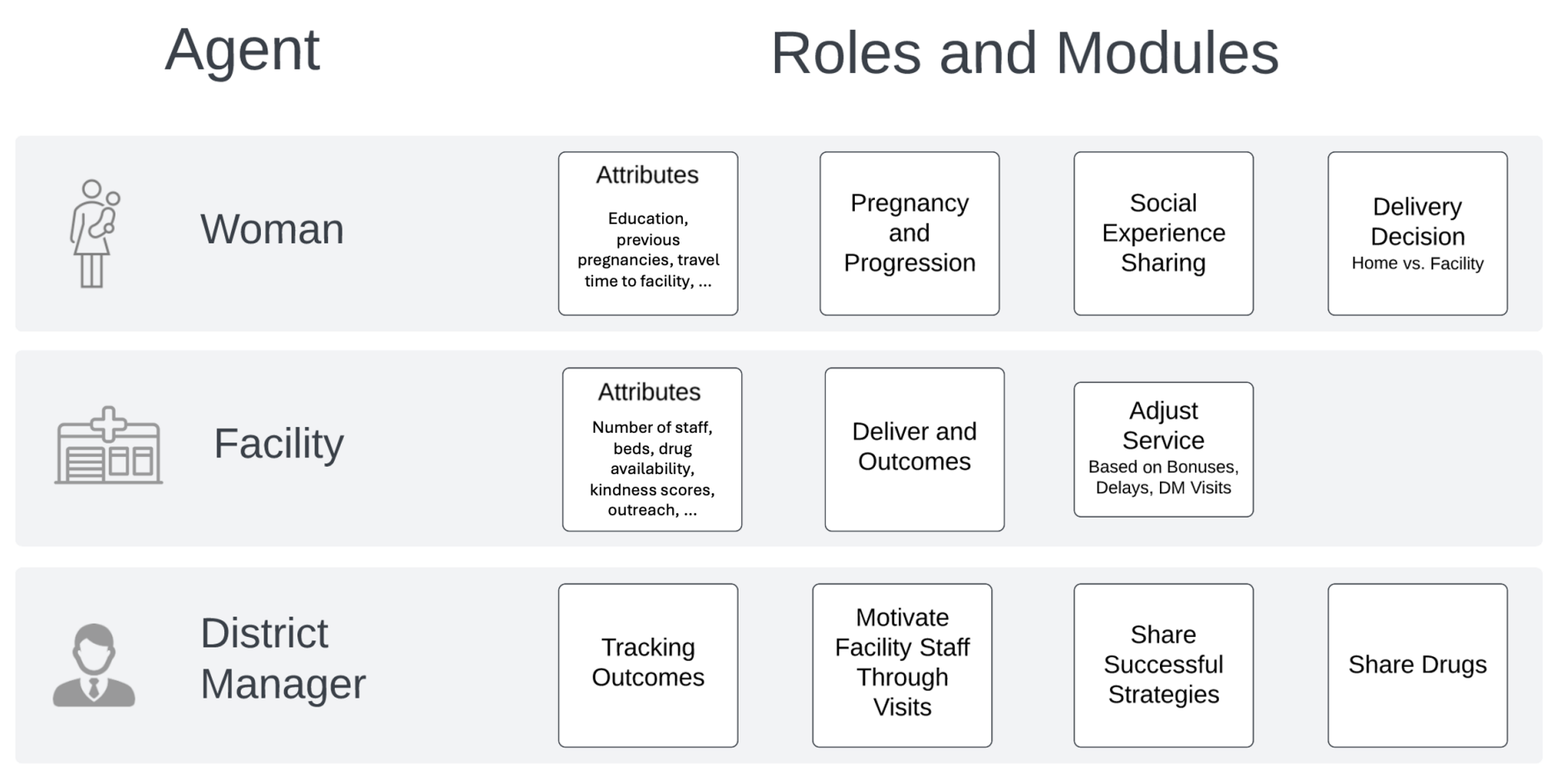

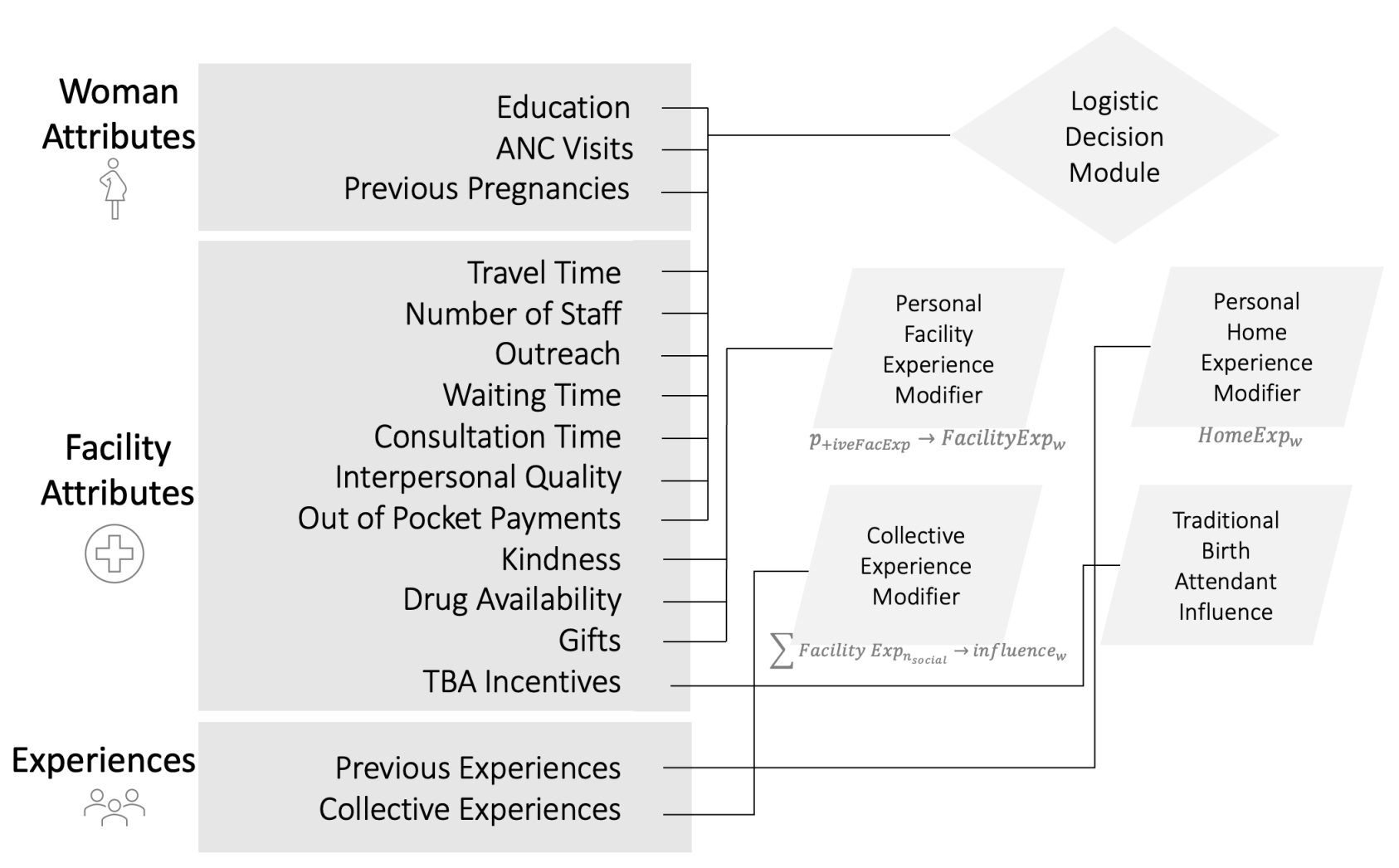

We modeled a representative district within the Pwani Region in Tanzania. Three key types of agents constitute the modeled entities: women of reproductive age (\(w\)), health facilities (\(f\)), and a district manager (m). Each type of agent has designated properties, state charts, and capabilities to progress and perform their predefined roles. We describe the building blocks of the ABM using the "PARTE" framework: Properties, Actions, Rules, Time, and Environment described in Hammond (2015). Figure 1 summarizes the key modules with which each agent is equipped to execute key decisions as active participants in the Pwani P4P program. We then proceed with an agent-level description of the modules.

Data sources & variable selection

Our study drew on various data sources for model formulation, parameterization, calibration, and validation. To inform the formulation of the model, we considered the demand- and supply-side factors shaping women’s decisions regarding where to deliver and a theory of how P4P would influence these, drawing on existing evidence regarding the supply- and demand-side effects of the P4P program in Tanzania, and the wider literature (Binyaruka et al. 2015; Borghi et al. 2013; Mayumana et al. 2017; Ministry of Health and Social Welfare 2012), and through engagements with stakeholders in Bagamoyo and Chalinze districts councils in Pwani Region, Tanzania, including district managers, facility in-charges and members of the facility governing committees.

Model parameters were derived from government reports on P4P in Tanzania (Ministry of Health and Social Welfare 2012). The modeled characteristics of facilities and the women were selected based on literature, previously described stakeholder engagements, and statistical analysis of P4P evaluation data, focused on facility and patient survey data and a survey of women who recently delivered (Binyaruka et al. 2015; Maiba et al. 2022; Mziray et al. 2022). Facility surveys from the baseline, midline and endline periods of the P4P evaluation were conducted in 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively. The survey covered 150 facilities, 1,500 patients and women, and 2,846 households in three regions in Tanzania. Eligible women were those who had delivered 12 months before the surveys. The selected facility attributes modeled are selected from the associated published statistical models (Binyaruka et al. 2015, 2018, 2023; Borghi et al. 2013). Facility-reported performance data submitted to the district were used as calibration targets to calibrate unknown facility parameters. The decision to deliver at the facility for childbirth by women was modeled using a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression based on data from the women’s survey (Binyaruka et al. 2023). This statistical model captures the supply- and demand-side factors that influence women’s choice of delivery. Table 2 summarizes the data sources and uses within the model.

| Data Source | Use | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Literature Review | To understand healthcare delivery and maternal and child health (MCH) in Tanzania. | Borghi et al. (2013), Binyaruka et al. (2015), Mayumana et al. (2017), Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (2012) |

| Stakeholder Interviews | To collect first-hand information on the operations of healthcare facilities, establish causal relationships and verify structural validity. | Maiba et al. (2022) |

| Focus Group Discussion | To gather detailed insights on the implementation of the P4P program. | Mziray et al. (2022) |

| Government Reports | Used for the model structure and parameterization of the P4P program. | (CHAI and Ministry of Health 2011) |

| Baseline P4P Survey | To provide model parameters, demographic information, healthcare access data, and health behavior insights. | N/A |

| Midline P4P Survey | To calibrate unobservable and unmeasured model inputs for improved model representation | N/A |

| Endline P4P Survey | To validate modeled outcomes against observed endline outcomes of the modeled facilities | N/A |

| Facility Attributes Data (Obtained from from P4P Survey) | To model facility characteristics related to performance and influencing women’s childbirth location decisions. Facility performance was used for validation and calibration. | Borghi et al. (2013), Binyaruka et al. (2018), Binyaruka et al. (2015), Binyaruka et al. (2023) |

| Multilevel Mixed-Effect Logistic Regression (Obtained from from P4P Survey) | To model women’s choice of facility for childbirth and verifying model relationships. | Binyaruka et al. (2023) |

Causal pathways of Pwani P4P underpinning the formulation of the ABM

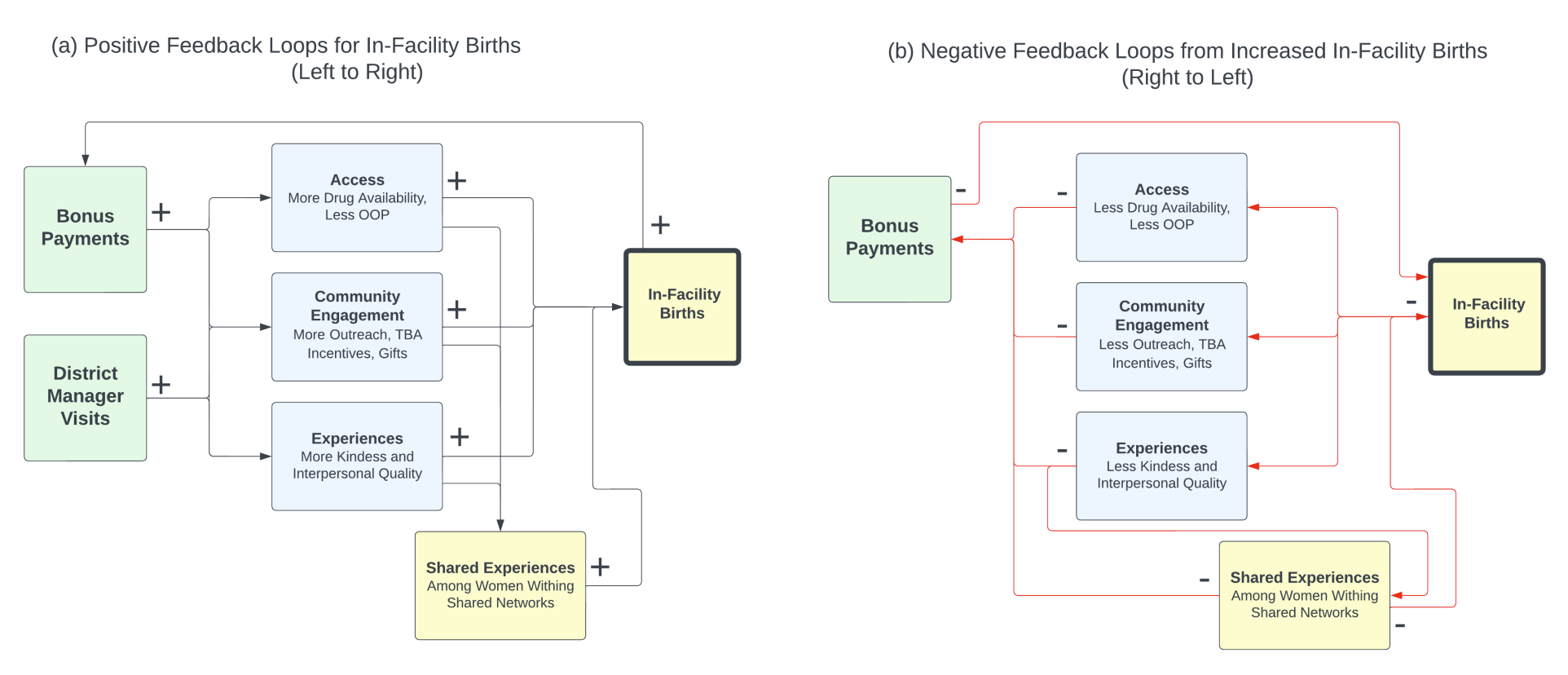

There are a variety of pathways through which the Pwani P4P program was envisaged to increase the coverage of institutional deliveries among pregnant women. On the supply-side, incentives for health workers are expected to increase motivation to provide incentivized services, improve the kindness of the provider, and reduce informal fees (such as out-of-pocket fees, or OOP). In addition, the funds for health facilities could be used to increase drug availability, cover transportation costs associated with community outreach activities, pay traditional birth attendants to refer women to facilities, and offer gifts to attending women. Increasing drug availability also reduces OOP for mothers who purchase out-of-stock drugs. These changes to service delivery are expected to increase demand for facility-based care (Anselmi et al. 2017; Binyaruka & Borghi 2017; Mayumana et al. 2017).

To explicitly quantify and model the demand-side effects, our ABM incorporated key drivers of demand increase with specific parameterization based on empirical data from the Pwani region. We estimated that P4P interventions would increase demand for facility-based deliveries through three primary mechanisms: (1) improved perceived experiences and quality of care, based on survey data from Binyaruka & Borghi (2017); (2) better access and reduction in OOP expenses, according to household expenditure data in household survey; and (3) community and word-of-mouth effects from positive experiences. Our model accounts for potential capacity strains through explicit modeling of bed availability and drug stock levels, all of which act as moderating factors that can dampen demand increases when facilities reach capacity constraints. All of these pathways have been confirmed in stakeholder interviews.

Through their involvement in facility performance verification and because of incentives from P4P, district health managers are expected to make more regular visits to facilities enrolled in the Pwani P4P program (Mayumana et al. 2017). This is expected to further motivate the facilities to deliver better care. In addition, district managers can allow the sharing of strategies between providers to encourage the adoption of best practices (i.e., community outreach) (Mziray et al. 2022). Managers are also incentivized to mitigate drug stock outs (i.e., where the facility runs out of essential medications) in facilities that experience high demand or payment delays to the facility. It is expected that managers may support facilities in mitigating stock-outs through, for example, facilitating drug sharing among facilities when supplies are low, further reducing the risk of stock-outs as revealed in stakeholder interviews.

Supply-side changes are expected to increase the acceptance of delivery care services among pregnant women. As women’s experience of care changes, this information is shared with other women, which influences the care-seeking behavior of other women. Alongside these positive causal pathways, there are potentially negative and unintended effects. Delays in expected bonus payments can adversely affect provider motivation and deteriorate experiences of delivering women, reducing future demand (Alonge et al. 2017; Ogundeji et al. 2016). Furthermore, additional demand for in-facility deliveries can reduce future demand through depletion of drug supplies and worsening of delivery experiences at the facility (owing to capacity and supply constraints). The positive and negative pathways to births in the facility associated with the Pwani P4P program are illustrated in Figure 2.

Facility agent

Facility agent properties

We model three facilities, \(|F|=3\), in the Bagamoyo district. The modeled facilities were selected to provide diverse characteristics and performance outcomes for the facility and the population in the catchment area. Facility names are masked in this model and are called facilities A, B, and C. At model initiation, the characteristics of each facility agent correspond to the baseline data from the associated facility and the household for their corresponding catchment areas. The selected facility attributes modeled are curated from published analyses ( Binyaruka et al. 2015, 2018, 2023; Borghi et al. 2013). The attributes of a facility agent \(f\) are static (remaining unchanged from baseline) or dynamic (changing based on bonuses, delays, and occupancy). The following list describes the attributes and classification of each attribute:

- Static Facility Attributes:

- Number of Staff at Baseline

- Number of Beds at Baseline

- Catchment Population (Number of women of reproductive age and their attributes)

- Average Waiting Time for Antenatal Visits at Facility in Minutes

- Dynamic Facility Attributes, Change in Time \(t\):

- Rate of Facility-Based Deliveries \(\textit{FB}_{f,t}\)

- Staff Interpersonal Quality \(\textit{IPQ}_{f,t} \in [0,1]\)

- Staff Kindness \(K_{f,t} \in [0,1]\)

- Drug Availability \(D_{f,t} \in [0,1]\)

- Out-of-Pocket Costs \(\textit{OOP}_{f,t} \in [0,1]\)

- Outreach Programs \(\textit{O}_{f,t} \in \{0,1\}\)

- Traditional Birth Attendant (TBA) Incentives \(\textit{TBA}_{f,t} \in \{0,1\}\)

- Gifts to Mothers \(G_{f,t} \in \{0,1\}\)

Dynamic attributes are updated monthly for each facility through counters of each event type: district births, in-facility deliveries, and delivery outcomes in the facility’s catchment area. Data used to parameterize each of the three facilities at baseline are collected from three data sources: (1) facility survey, (2) stakeholder interviews for baseline TBA incentives and Gifts to mothers (\(\textit{TBA}_{f,1}\) and \(G_{f,0}\)) (3) household survey (for interpersonal quality, kindness, waiting time, and out of pocket payments), and (4) facility performance reported to the Pwani P4P program as described in Section 3.2. The baseline period corresponds to January 2011. The agent’s actions and rules outlined in Section 3.10 dictate what happens in the proceeding periods.

Facility agent actions & rules

Upon initiating and loading baseline values, a facility provides maternal care services in its catchment area and progresses through its performance cycle, bonus cycle, and district manager cycle.

Performance Evaluation and Bonus Cycles. Every six months after initiating the model, facilities undergo an evaluation in which all deliveries in their corresponding catchment area are aggregated over the performance period PP. Then, if a bonus is earned, a bonus payment is made where its effects are observed in the bonus period BP. Figure 3 visually represents the performance and bonus payment cycles.

The coverage performance of a facility \(f\), or proportion of facility-based births at \(f\), \(\%\textit{FB}_{f,\textit{PP}}\), during the performance period PP is calculated as:

| \[\%\textit{FB}_{f,\textit{PP}} = \frac{\textit{# of deliveries at f during PP}}{\textit{# of births in catchment population of f during PP}}\] | \[(1)\] |

The difference between \(\%\textit{FB}_{f,\textit{PP}}\) and \(\%\textit{FB}_{f,\textit{PP}-1}\) determines whether the facility \(f\) receives a bonus for its performance during the performance period \(PP\). The difference is called the indicator \(I_{f,\textit{PP}} = \%\textit{FB}_{f,\textit{PP}} - \%\textit{FB}_{f,\textit{PP-1}}\), and must equal or exceed a target value that depends on the previous performance period’s \(\textit{FB}_{f, (\textit{PP}-1)}\), calculated as follows:

| \[ \textit{Target}_{f, \textit{PP}} = \begin{cases} 0.15 & \text{if } \textit{FB}_{(f, \textit{PP}-1)} < 0.2\\ 0.1 & \text{if } 0.2 \leq \textit{FB}_{(f, \textit{PP}-1)} < 0.4\\ 0.05 & \text{if } 0.4 \leq \textit{FB}_{(f, \textit{PP}-1)} < 0.85\\ \text{Maintain} & \text{if } 0.85 \leq \textit{FB}_{(f, \textit{PP}-1)} \\ \end{cases}\] | \[(2)\] |

If \(I_{f,\textit{PP}} \geq \textit{Target}_{\textit{PP}}\), then the facility \(f\) receives a full bonus, \(\textit{Bonus}_{f,\textit{PP}} = 1\). If not, but \(I_{f,\textit{PP}} \geq 0.75* \textit{Target}_{\textit{PP}}\), then the facility \(f\) receives half a bonus, \(\textit{Bonus}_{f,\textit{PP}}=0.5\). Otherwise, if none of the previous conditions are met, then the facility \(f\) does not receive a bonus; \(\textit{Bonus}_{f,\textit{PP}}=0\). Note that if \(f\) performs in the previous performance period \(\textit{FB}_{ (f, \textit{PP}-1)} \geq 0.85\), then \(f\) can receive a full bonus by maintaining \(\textit{FB}_{(f, \textit{PP})} \geq 0.85\). Note that a facility that achieved \(\textit{FB}_{(f, \textit{PP}-1)} \geq 0.85\) can only receive a full bonus in PP after maintaining it above the 0.85 threshold.

Performance Bonus Payment Cycles. At the end of the performance period PP, changes related to the bonus occur. These changes are of two types: (1) resource-dependent changes and (2) motivational responses from the staff to bonuses. In general, gaining a bonus is associated with improving facility characteristics, and losing a bonus is associated with deterioration of facility characteristics. Bonus recipients experience increases in their drug supplies, motivation, and outreach initiatives that last the duration of the performance cycle (6 months). Changes in facility characteristics are dependent on the bonus amount \(\textit{Bonus}_{f,\textit{PP}}\). Table 3 describes the bonus-induced changes to the attributes of the facility in month \(t+1\) after a facility earns a bonus.

The motivational responses of the staff to bonuses, if earned, occur one month after the end of the performance cycle PP. The motivational responses of the staff manifest themselves in the model as improvements in the kindness kindness and interpersonal quality \(\textit{IPQ}\) parameters for the facility, which further improve the rate of in-facility deliveries at the facility. One thing to note is that Kindness \(K\) is capped at 0.9 in Table 3; however, it is still possible for Kindness to increase beyond 0.9 during district manager (DM) visits. As mentioned above, the extent of change in these values due to bonuses is primarily informed by the input of stakeholders.

Three months after the end of each performance period \(\textit{PP}\), a facility \(f\) is scheduled to receive the bonus amount \(\textit{Bonus}_{f,\textit{PP}}\). According to Table 1, a bonus period BP is always scheduled three months after the performance period PP. For example, the first PP ends in June 2011, and the first BP is scheduled in September 2011. Resource-dependent changes are assumed to occur at the time a bonus is received because bonus funds immediately enable additional resources. Once a facility \(f\) receives the bonus amount, the facility can purchase more drugs, reduce out-of-pocket fees, and provide gifts, traditional birth attendant (TBA) incentives, and outreach activities.

| Case | \(\textit{Bonus}_{f,\textit{PP}}\) | Changes to Facility Attributes at \(t+1\) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 |

Incentives for \(\text{TBA}_{f,t+1} = \text{TBA}_{f,0}\) Outreach \(\text{O}_{f,t+1} = \text{O}_{f,0}\) Staff \(\text{IPQ}_{f,t+1} = \text{IPQ}_{f,0}\) Kindness \(K_{f,t+1} = K_{f,0}\) Drugs \(D_{f,t+1} = D_{f,0}\) Gifts \(G_{f,t+1} = 0\%\cdot G_{f,0}\) \(\text{OOP}_{f,t+1} = \text{OOP}_{f,0}\) |

| 2 | 0.5 |

Incentives for \(\text{TBA}_{f,t+1} = 1\) Outreach \(\text{O}_{f,t+1} = \max(\text{O}_{f,t}, \text{random with 50% chance of }1)\) Staff \(\text{IPQ}_{f,t+1} = \max(\text{IPQ}_{f,t}, 0.8)\) Kindness \(K_{f,t+1} = \max(K_{f,t}, 0.8)\) Drugs \(D_{f,t+1} = \max(D_{f,t}, 0.8)\) Gifts \(G_{f,t+1} = 0\%\cdot \max(G_{f,t}, \text{ 50% chance of }1)\) \(\text{OOP}_{f,t+1} = \text{OOP}_{f,t} \cdot 0.9\) |

| 3 | 1 |

Incentives for \(\text{TBA}_{f,t+1} = 1\) Outreach \(\text{O}_{f,t+1} = 1\) Staff \(\text{IPQ}_{f,t+1} = 1\) Kindness \(K_{f,t+1} = \max(K_{f,t}, 0.9)\) Drugs \(D_{f,t+1} = 1\) Gifts \(G_{f,t+1} = 1\) \(\text{OOP}_{f,t+1} = \text{OOP}_{f,t} \cdot 0.8\) |

| 4 | Delay Effects |

Incentives for \(\text{TBA}_{f,t+1} = 0\) Outreach \(\text{O}_{f,t+1} = 0\) Staff \(\text{IPQ}_{f,t+1} = \text{IPQ}_{f,t-1} - 0.1 \;\; \text{while } \text{IPQ}_{f,t} \geq 0.6\) Kindness \(K_{f,t+1} = K_{f,t-1} - 0.1 \;\; \text{while } K_{f,t} \geq 0.5\) Drugs \(D_{f,t+1} = D_{f,t-1} - 0.1 \;\; \text{while } D_{f,t} \geq D_{f,0}\) Gifts \(G_{f,t+1} = 0\) \(\text{OOP}_{f,t+1} = \text{OOP}_{f,t} + 0.1 \;\; \text{while } \text{OOP}_{f,t} \leq 1\) |

Delays in Bonus Payments. Performance periods and bonus payments occur according to Table 1 and Figure 3. The changes induced by bonuses occur during the month \(t\) when a bonus payment is received. Practically, bonus payments were not always made according to schedule, creating a payment delay. A facility agent \(f\) is considered to be experiencing a bonus payment delay at month \(t\) if it was scheduled to receive a payment, but no payment was made. Based on staff interviews from sampled facilities, bonus delays affected several aspects of facility performance. During a delay in the payment of the bonus, a facility would have less funds to replenish drug stocks and gifts and would be more inclined to increase informal fees for delivering mothers. Furthermore, facility personnel would be less motivated to provide the same delivery experience. Consequently, a bonus payment delay has a time-related effect on the facility, whereby every month of delay is operationalized in row 4 of Table 3. The changes represent a time-dependent decrease in drug availability, interpersonal quality and kindness of staff, and an increase in OOP. Additionally, incentives for TBAs and outreach programs are stopped if a bonus payment is delayed.

Facility Capacity & Occupancy. Each facility agent is generated with a static number of beds representing its capacity. However, facilities accept delivering women even if the beds are occupied. Therefore, we introduce a capacity variable set to the number of beds plus a capacity relaxation amount so that the capacity of the facility is \(C_f = \text{beds} + R\), where \(R\) is a relaxation parameter applied uniformly to all facilities. Beyond \(C_f\), the facility \(f\) cannot accept deliveries, and a pregnant woman agent who wishes to deliver in an at-capacity facility will deliver elsewhere; an out-of-system delivery. These deliveries are recorded and noted, but are not a key outcome of this model. The value of the relaxation parameter \(R\) is a calibration parameter where we experiment with \(R =\) 1, 2, or 3.

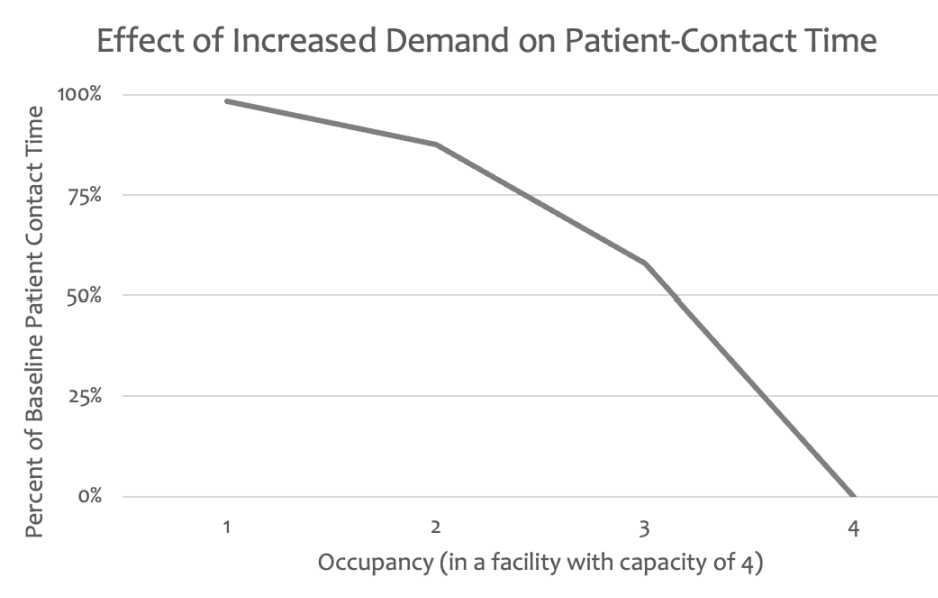

If the number of women who hope to deliver in a facility \(f\) exceeds the number of beds available but is \(\leq C_f\), the staff of a facility provide less contact time with women (total patient-contact time) during their stay at the facility. This facet represents the demand-capacity balance as shown in Figure 2 in the Worse Experiences red box. An increase in occupancy from 20% to 30% would lead to a smaller decrease in patient contact time than an increase in occupancy from 70% to 80% as we use a logistic function to create an occupancy factor that follows an S-shaped curve to represent this relationship. The function is described in Appendix C.

Woman agent

We generate 1,866 women agents \(W\) to represent women of reproductive age who reside in the catchment area of one of the three modeled facilities \(f\). Each simulated woman agent \(w\) is assigned to a catchment area of a facility \(f\) such that \(w \in W_f \subset W\). The distribution of each attribute of a woman \(w\) is conditional on the facility to which they are assigned. The number of women assigned to each facility \(|W_f|\) reflects the actual number of women of reproductive age in the area of the facility. Census data from National Bureau of Statistics (2015) were used to estimate \(|W_f|\) of the population in the catchment area \(P_f\) multiplied by the proportion of women of reproductive age \(\%\textit{WRA}\). \(\%\textit{WRA}\) was estimated from national rates applied to local population figures after reviewing census data and consulting local demographers. The formula \(|W_f|=\%\textit{WRA} \times P_f\) approximates the number of women agents in each facility’s catchment area.

Woman agent properties

Once a woman \(w\) is generated and assigned to a facility \(f\), the properties that are relevant to the demand for delivery care are sampled from the conditional distributions shown in Table 4. We consider the demographic and epidemiological characteristics of the catchment area static. Therefore, we used average distributions from the 3 waves of survey data, grouped by facility, to determine static woman properties. For the three categorical variables, education, previous pregnancies, and antenatal visits, a uniform random variable \(u\) was sampled and compared to the cumulative distribution of levels to assign a category to the woman agent \(w\). The travel time from agent \(w\) to assigned facility \(f\) is estimated using the average facility-specific travel time \(\overline{TT}_{f}\) from the multi-year survey. Approximately 67 observations per facility \(f\) are used to estimate \(\overline{TT}_{f}\). The travel time of a woman agent \(TT_{\textit{w-to-f}}\) is assumed to be uniformly distributed around \(\overline{TT}_{f} \pm 50\%\), sampled as \(TT_{\textit{w-to-f}} = \overline{TT}_{f} * (u + 0.5)\) where \(u \sim\) uniform[0,1]. The correlations between the woman covariate (including travel time) were found to be minimal and assumed to be independent of each other.

| Variable | Category | Facility A | Facility B | Facility C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | No education | 12.0% | 22.3% | 17.4% |

| Some primary education | 8.8% | 16.9% | 3.3% | |

| Primary/some secondary education | 68.8% | 58.5% | 72.4% | |

| Secondary/above education | 10.4% | 2.2% | 6.9% | |

| Previous Pregnancies | 0 | 24.1% | 24.1% | 24.1% |

| 1+ | 75.9% | 75.9% | 75.9% | |

| Antenatal Visit (ANC) | 4+ ANC visits | 67.4% | 59.9% | 65.3% |

| Less than 4 ANC visits | 32.6% | 40.1% | 34.7% | |

| Travel Time to facility in Minutes | 14.67 | 39.77 | 46.87 | |

A woman agent’s \(w\) decision-making is also influenced by an additional set of factors, referred to as modifiers \((M_{\textit{fExp}}, M_{\textit{hExp}}, M_{\textit{social}}, M_{\textit{TBA}})\) including \(w\)’s prior delivery care experience at the facility and at home, delivery care experience at the facility among peers within the social network, and TBA influence (TBA incentives to refer women to the facility). Details on how these modifiers shape a woman’s delivery decision are provided in Section 3.32. In each simulation run, a social network is created for each woman agent \(w \in W\), connecting the agent to \(n_{\textit{social}}\) random women agents within the same area. The mechanisms of influence will be clarified later in Section 3.26.

Woman agent actions & rules

A woman agent’s decision regarding the place of delivery is determined by: (1) woman attributes, (2) facility characteristics, and (3) individual and shared experiences. The decision rule is shaped by the probability determined by a predictive logistic regression model (binyaruka et al. 2023), prior to this probability being adapted by the modifiers as detailed below.

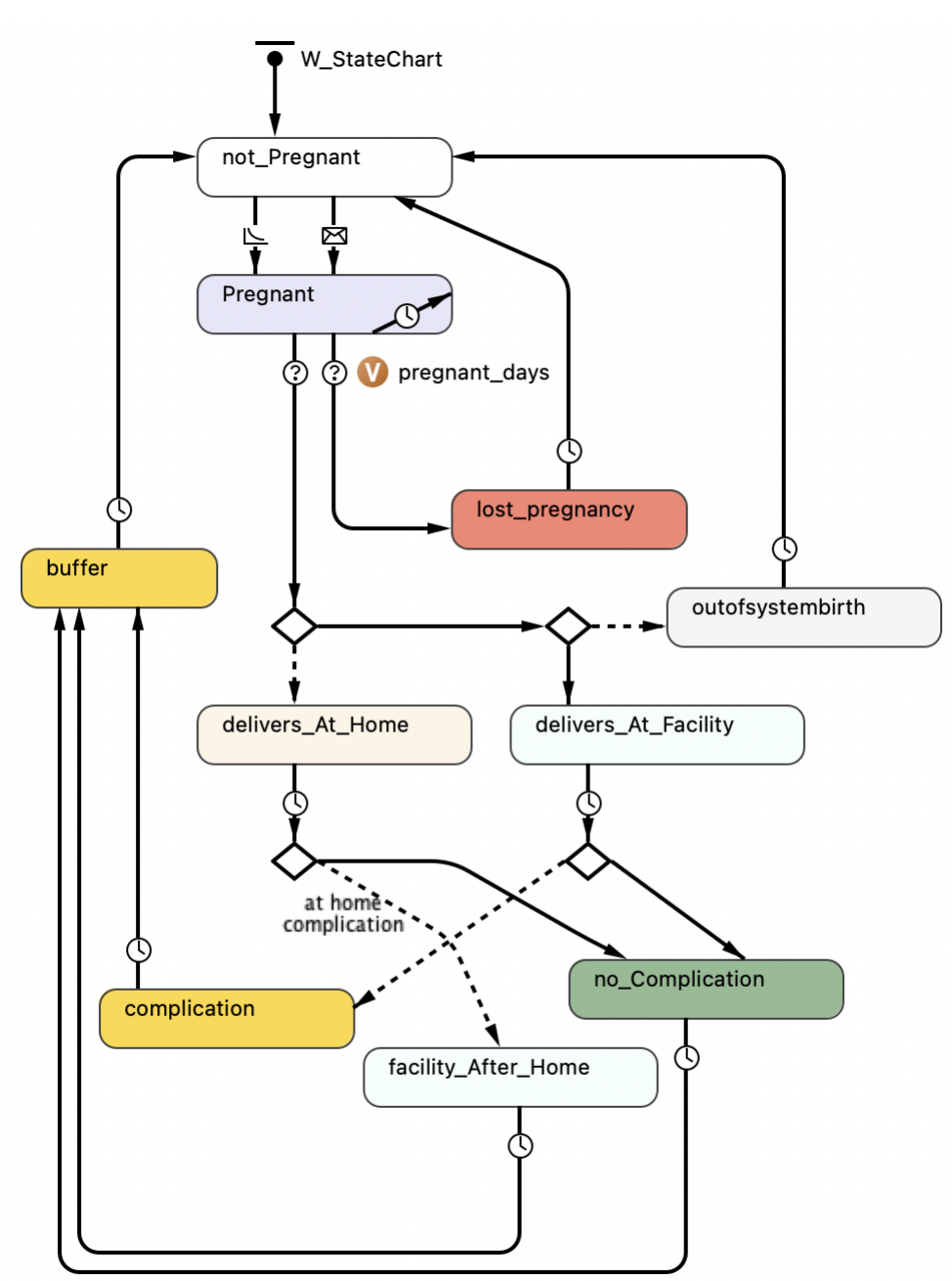

Women agents progress through the pregnancy and delivery state chart as in Figure 4. A woman \(w\) is initiated as pregnant with probability \(p_{\textit{PregnantInitiation}}\). If \(w\) is initiated as pregnant, then it has a pregnancy duration of 270 days (9 months) \(\textit{pregnantDays} \sim\) uniform(0,270). The pregnancy period is assumed to be deterministic, as it is not directly relevant to the purpose of the model. If a woman is not pregnant at initiation, then the probability of becoming pregnant is set at \(p_{\textit{pregnant}} = 0.015\) per month. In other words, 18% of women of reproductive age become pregnant each year (derived during model calibration). During pregnancy, \(w\) can experience a lost pregnancy before labor (due to a miscarriage or stillbirth) with a probability of \(p_{\textit{lostpregnancy}}=0.2\). This was calculated from the prevalence of stillbirths, which is 0.0217 (21.7 per 1000 is the prevalence of stillbirths in 2019) (Hug et al. 2020). Furthermore, 49% of stillbirths occur before labor (\(100\% - 51\%\)), where 51% is from Sub-Saharan Africa in Lawn et al. (2016). Multiplying these values together and then adding the 0.189 risk of miscarriage from Dellicour et al. (2016) produces the value of 0.2 as the probability that a pregnancy will be lost. If \(w\) experiences a lost pregnancy, \(w\) returns to the non-pregnant state after 14 days, as reported in Mayo Clinic (2021) and then experiences the same monthly pregnancy rate \(p_{\textit{pregnant}}\).

Mothers of pregnancies that are not lost before labor face the decision of whether to deliver at the facility or at home. At each delivery site (home or facility), the probability of a complication during delivery is \(p_{\textit{complication}}=0.46\), as reported in Danilack et al. (2015). If \(w\) chooses to deliver at home and experiences a delivery complication, \(w\) is referred to the facility (facility-after-home state). If \(w\) chooses to deliver in the facility and develops a complication, the delivery is recorded as an out-of-system birth (such events are referred to a higher level of care). All deliveries (including complications, if any) take six weeks before a woman returns to the non-pregnant state, as noted for most women in Jackson & Glasier (2011). The probability of getting pregnant again is then the default \(p_{pregnant}\). All deliveries at the facility occupy a bed for one day. In the case of complications, women are referred to the local hospital for further treatment, but for modeling purposes, we still count this as occupying a bed at the original facility for one day before transfer.

Decision-making of a woman agent \(w\) is influenced by her previous birth experience. Dynamic variables of the home and facility experience updates based on the latest home or facility experience. The home experience is determined by whether home complications occurred in the past. When a complication occurs during home delivery, \(\textit{HomeExp}_w \in \{-1, 1\}\) takes a value of \(1\), which makes the woman prefer facility delivery in the future. If a delivery is \(w\)’s first, \(\textit{HomeExp}_w =1\) with probability \(p_{\textit{complication}}\). If the woman \(w\) had a safe previous home delivery, \(\textit{HomeExp}_w\) takes a value of \(-1\), which makes the woman prefer home delivery in the future. After \(w\) delivers in a facility, \(\textit{FacilityExp}_w\) is obtained from \(p_{\textit{+iveFacExp}}\); a weighted composite score of the level of drug availability \(D_f\), the kindness of the staff \(K_f\), and the gifts received \(G_f\) when giving birth at \(f\). The weights for \(p_{\textit{+iveFacExp}}\) are shown in Equation 3 with all \(f\) parameters standardized to be between 0 and 1.

| \[ p_{\textit{+iveFacExp}} = 0.4*D_f + 0.4*K_f + 0.2* G_f\] | \[(3)\] |

For women agents, the baseline facility characteristics are used to calculate \(p_{\textit{+iveFacExp}}\) above. The value of \(p_{\textit{+iveFacExp}}\) calculated using Equation 3 is then used to sample \(\textit{FacilityExp}_w = +1\) with probability \(p_{\textit{+iveFacExp}}\), and \(\textit{FacilityExp}_w = -1\) otherwise, each time \(w\) decides. At the time of a decision, a \(w\) requests and aggregates \(\sum{\textit{FacilityExp}_n}\) for all \(n_{social}\) on the social network. Then, \(\textit{influences}_w\) is determined as follows:

| \[ \textit{influences}_w= \begin{cases} -1, & \text{if}\ \sum{\textit{FacilityExp}_n}<0 \\ 0, & \text{if}\ \sum{\textit{FacilityExp}_n}=0 \\ 1, & \text{if}\ \sum{\textit{FacilityExp}_n}>0 \\ \end{cases}\] | \[(4)\] |

Woman agent delivery decision

The characteristics of the facility closest to \(w\) are visible to women in \(f\) catchment area as are the occupancy effects. The decision of the woman agent for the delivery site is adapted from Binyaruka et al. (2023) and modified using the insights of the stakeholders. The study by Binyaruka et al. (2023) first included all variables in the multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression model. Then, this model was reduced using backward stepwise regression, dropping the variable with the highest p-value at each step for thirteen steps. Correlation analysis was also performed to explore the collinearity of the supply-side and demand-side determinants of utilizing facility-based delivery care. The correlation analysis used collinearity diagnostics of tolerance \(\leq\) 0.1 and VIF \(\geq\) 10 as thresholds of concern. However, for each correlated pair identified, at least one variable had already been dropped from the regression as non-significant, so no further variables needed to be removed due to correlations. The final reduced model only includes significant supply-side variables described in Section 3.8 and demand-side variables described in Section 3.24. The coefficients used in the regression are listed in Appendix B.

The decision at delivery is sequenced as follows:

- The woman collects the closest facility \(f\)’s attributes and occupancy level. Specifically, \(w\) collect the following for \(f\):

- Number of occupied and unoccupied beds

- Previous month’s average patient contact time multiplied by an occupancy factor.

- Previous month’s average waiting time

- Drug availability

- Staff interpersonal quality

- Staff kindness

- Previous month’s average out-of-pocket costs

- The woman collects experiences from the \(n_{social}\) women agents in her social network to calculate the net \(\textit{influences}_w\) of her social network based on their facility experiences (if any) based on the \(\textit{influences}_w\) variable (Equation 4).

- Run the logistic model using \(w\)’s properties and information obtained in step 1 and obtain \(p_{\textit{facility delivery}}\) as from Equation 5 following Binyaruka et al. (2023).

- Aggregate the social and personal experience from

\(\textit{influences}_w\), \(\textit{HomeExp}_w\), and \(\textit{TBA}_f\) in the modifier equation using \(w\) weights for each. - Compute the modified probability of giving birth at the facility \(p_{w@f}\) using Equation 6.

The pre-modified probability that a woman agent \(w\) delivers in a facility is calculated as shown in Equation 5:

| \[ p_{\textit{facility delivery}}=\frac{e^y}{1+e^y}\] | \[(5)\] |

Where \(y\) is the dot product of the values of the variables and the coefficients of the logistic regression vector from the table in Appendix B. Then, the modified and final probability that woman \(w\) delivers at facility \(f\), \(p_{w@f}\), is calculated by adding all the weighted modifiers \(\textit{ModSum} = \textit{FacilityExp}_w*M_{\textit{fExp}} + \textit{HomeExp}_w*M_{\textit{hExp}} + \textit{influences}_w*M_{\textit{social}} + \textit{TBAincentive}_f*M_{\textit{TBA}}\) then applying the following to the probability:

| \[ p_{w@f}= \begin{cases} p_{\textit{facility delivery}}*(1+\textit{ModSum}), \\ \hspace{3cm} \text{if}\ \textit{ModSum}<0 \\ p_{\textit{facility delivery}}*(1+\textit{ModSum}*(1-p_{\textit{facility delivery}})),\\ \hspace{3cm} \text{if}\ \textit{ModSum}\geq 0 \\ \end{cases}\] | \[(6)\] |

Refer to Figure 5 for an illustration of the variables feeding into the logistic regression that would calculate \(p_{w@f}\). A pregnant woman agent \(w\) delivers in facility \(f\) if \(u \leq p_{w@f}\) where \(u \sim \text{uniform}[0,1]\).

District health manager

The model generates one m agent to perform the functions of district health managers in the Pwani P4P scheme. The properties that define the m agent are the frequency of facility visits, measured in months between visits, and visit duration. An m visits quarterly (every three months). We assume that m visits happen concurrently (within the same month) for all facilities, and so it is likely they were visited on the same day/week in reality. During visits, the m would induce changes to facility characteristics due to the motivational effect of visits and through the facilitation of resource and knowledge exchange between facilities. The changes associated with m visits are described in the subsection below.

District manager actions & rules

Quarterly Visits to Facilities. During their routine visits, district manager visits induce temporary changes in provider attitudes and motivation around the time of a scheduled visit. Before and after m’s visit, facility agents may be temporarily motivated to provide a higher quality of care manifested in higher kindness \(K\) and interpersonal quality IPQ. Therefore, we model a 50% chance a facility would increase its \(K\) and IPQ by ten percentage points in response to a scheduled m agent visit. If there is a change, the improvements last for \(\textit{VisitDuration}\) in days, starting \(\textit{VisitDuration}/2\) days before to \(\textit{VisitDuration}/2\) days after, after which \(K\) and IPQ revert to pre-visit levels. The duration of m’s agent visit effects, VisitDuration, is a calibration parameter that can vary in the calibration procedure to achieve the best fit to observed facility performance.

Bonus Payment Delay Mitigation. If a district manager agent m visits a facility agent \(f\) and the facility is experiencing a bonus payment delay, the m agent can offset the delay-induced decrease in provider motivation by providing assurances of the upcoming payment. Specifically, \(f\)’s staff interpersonal quality IPQ, staff kindness \(K\), outreach \(O\), and out-of-pocket OOP will revert to pre-delay levels. For mitigation to occur, the m agent visit and bonus payment delay must occur within the same month. Once the mitigation occurs, changes in the previously listed facility agent attribute restart degrading in the following month of the delay.

Sharing Best Practices. District managers facilitate strategy-sharing across facilities regarding the achievement of bonus targets to promote best practices. In the model, as described in stakeholder interviews, the m agent can share best practices around three demand-inducing strategies: TBA incentives, kindness K, and outreach O. For facilities that do not already have the highest values for these variables, strategy-sharing by the district manager enables the facility to enhance these attributes to match the best performer of the 3 facilities modeled, but only if they receive a bonus payment to fund these enhancements. Facility-level counters track all m mitigation and strategy-sharing events.

Drug Sharing Across Facilities. A district manager visit facilitates drug sharing between facilities when there is a payment delay, provided that specific drug supply conditions are met at both the donor and recipient facilities. The sharing occurs if the donor facility’s drug supply level, known as the Donor Threshold \(DT\), is at least as high as the recipient facility’s threshold \(RT\%\) plus twice the amount to be shared, i.e., \(DT \geq RT\% + 2 \times Sharing\%\). When these conditions are satisfied, the donor facility transfers a portion of its drug supplies, specified by \(Sharing\%\), to the recipient facility. Importantly, this transfer ensures that the recipient facility’s drug supply does not surpass the remaining supply at the donor facility after the sharing. The parameters \(RT\%\) and \(Sharing\%\) are calibration parameters used to fine-tune the model.

Timeline & event sequence

The model runs on a daily time step. Outcomes at the facility level are reported and analyzed monthly. The model time \(t\) represents the time in months since model initiation. Model time \(t = 0\) corresponds to December 2010, the simulation baseline period. The model begins at time \(t = 1\), corresponding to January 2011. The model’s time horizon is 36 months, or three years, ending in January 2014, covering six performance periods, PP, and five bonus payments.

The model initiates by generating the three modeled facilities and reading their baseline attributes. The baseline facility attribute values are shown in Table 11. Then, \(|W_f|\) women agents \(w\) are generated for each facility with attributes sampled from Table 4. Of the women agents generated, \(p_{\textit{PregnantInitiation}}\) of the women agents are generated in the pregnant state and assigned a random stage of pregnancy. The model then makes daily timesteps with women progressing through their statecharts as described in Figure 4. At the end of each month, facility-level attributes (facility-based delivery rates and characteristics) are updated. Then, the time variable updates as time progresses, \(t = t + 1\). At the end of a performance period PP, 6-month aggregations occur for bonus evaluations as shown in Equation 2. Where a bonus payment is scheduled and \(\textit{Bonus}_{f,PP}>0\), delay effects ensue as described in Table 3. Once the timestep \(t\) reaches a month where a bonus payment is made, the bonus effects are manifested according to Table 3. The above-described sequence continues until \(t=36\) months.

Model verification, calibration, and validation

Before detailing the analytical steps and experiment design, we first distinguish the three quality-assurance activities applied to the model. Verification asks whether the agent code correctly implements the intended logic; calibration selects parameter values that best reproduce a training data set; and validation evaluates how well the calibrated model explains data that were not used for calibration. The next three subsections describe, in that order, how each task was carried out.

Model verification

During the development of the model, features and agent capabilities were added sequentially. Following each integration, a thorough inspection was conducted to verify the integrity of the coding and the successful implementation of new elements. Debugging was an ongoing process throughout the development journey, ensuring the reliability and efficiency of our model.

To ensure the internal consistency of the ABM, we conducted a series of steps for model verification. Firstly, the mathematical coherence of the deterministic (i.e., bonus effects) and stochastic (i.e., woman agent decisions) components was assessed. This entailed inspection of model equations and their implementation in the simulation software, exploring behavior in terms of model outcomes when varying parameter settings. Inconsistencies were noted, debugged, and addressed. Second, we evaluated the long-term behavior of the ABM and its stability during simulations and emergent behavior. Lastly, we conducted a robustness analysis by testing the model performance under various parameter settings and incorporating small random perturbations. This helped ensure that the model’s results remained consistent despite uncertainties in model parameters, reinforcing the model’s internal validity.

Calibration

To calibrate the ABM, we defined a structured search space comprising twelve input parameters that lack direct empirical estimates. These parameters were varied across discrete, stakeholder-informed ranges to explore plausible behavioral and system dynamics. This is done to align the facility performance metrics generated by the ABM with the empirically reported performance outcomes from the actual facilities in the first 24 months of program implementation. Calibration parameters are listed below and categorized by the agent they relate to:

- Facility Agent

- Facility Capacity Relaxation \(R\) (1, 2, 3)

- Occupancy Adjustment (0, 1, 2)

- Woman Agent

- Facility Experience Modifier \(M_{\textit{fExp}}\) (0.3, 0.35)

- Home Experience Modifier \(M_{\textit{hExp}}\) (0, 0.025, 0.05)

- Social Network Modifier \(M_{\textit{social}}\) (0.3, 0.35)

- Traditional Birth Attendant Modifier \(M_{\textit{TBA}}\) (\(1-M_{\textit{social}} - M_{\textit{hExp}} - M_{\textit{fExp}}\))

- Size of Social Network \(n_{\textit{social}}\) (3, 4, 5, 6)

- Percent of Women Pregnant at Initiation \(p_{\textit{PregnantInitiation}}\) (0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.10)

- District Manager Agent

- Duration of DM Visit Effects \(\textit{VisitDuration}\) (0.5, 1)

- Drug Sharing Threshold \(RT\%\) (50%, 60%)

- Drug Sharing Rate \(\textit{Sharing\%}\) (5, 10)

A total of 13,824 parameter combinations were scanned in the search grid, with 10 replications ran for each combination of parameters. We use least-squares fitting to identify the combination of values of the above parameters that closely match the reported facility-reported delivery rates in the first 4 bonus periods (the last two bonus periods are used for validation purposes). Using a simple search approach based on a grid search methodology, we iteratively evaluated the predetermined combinations of parameter values spanning the plausible parameter space. For each parameter, we defined a range of potential values based on literature and expert input, then systematically tested combinations to identify those that minimized error between simulated and observed values.

Validation

Structural and Face Validity. The structural and face validation of the ABM was carried out through the active participation of stakeholders in the modeling process, according to the principles of participatory modeling. Staketakeholders contributed to the structure of the model by providing information about the real system through workshops organized by the research team in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Attendees helped refine the roles and interactions of agents, guided the inclusion of essential processes and behaviours, and provided context-specific information. Multiple iterations of the model were shared with stakeholders, and their feedback was instrumental in refining the model’s structure to align closely with the complexities and nuances of the health system. The involvement of these stakeholders throughout the modeling process not only enhanced the structural validity of the ABM but also promoted the model’s acceptance and future applicability in policy and decision-making.

External and Cross-Validation. After fixing the optimized calibration parameters, external validation involves testing the model against data not used in any part of the model’s development or calibration processes to assess its predictive performance. This helps to verify that the model’s predictions are accurate not just for the data it was calibrated with (which could potentially lead to overfitting) but also for other data in the same domain. We use facility-reported performance from months 30 to 36 (the last modeling performance period) to assess the model’s external validity.

For cross-validation, we compare the output of our model with two other data sources: (1) the outputs of a system dynamics model (SDM) that studies the effects of P4P on drug availability and demand for care delivery in the same context (Cassidy et al. 2025), and (2) the performance data from the control facilities in the Pwani region that did not participate in the P4P program.

In the first stage of cross-validation, we compared the trends and patterns observed in both the ABM and the SDM to gauge the consistency and validity of our findings related to these variables. Any discrepancies identified between the models offer an opportunity to reassess our assumptions and adjust the model parameters.

Second, by comparing our model’s predictions for the control facilities (without P4P) to the actual observed performance in these facilities, we can evaluate the model’s ability to accurately capture the system dynamics in the absence of the P4P initiative. This offers a crucial validity check for our model, enabling us to test its ability to mimic real-world outcomes in different circumstances.

Experiment design and settings

We use the validated simulation model to run several scenarios to identify how changes in P4P implementation (payment delays) and district manager visits affect program outcomes. First, three P4P implementation scenarios are simulated: (1) No P4P, (2) P4P with payment delays, and (3) P4P without payment delays. For scenarios (2) and (3) above, we test a further scenario modification: no \(m\) visits (so that the effects of any delays in receiving any bonus payments cannot be mitigated and \(m\) cannot facilitate strategy sharing or have any other positive motivational influences), as shown below. We ran 500 replications for each scenario to capture model stochasticity and infer potential divergence in trajectories, if any.

- (1) No P4P

- (2) P4P, delays

- (2.1) P4P, delays, No \(m\) visits

- (3) P4P, No delays

- (3.1) P4P, No delays, No \(m\) visits

Model implementation

The implementation of our model was carried out using AnyLogic v8 University Researcher Edition. A model pseudo code can be found in Appendix H. Anylogic’s platform allowed us to implement intricate agent-based configurations, behaviours, and interactions. The platform can also host the model’s user-friendly interface to facilitate interaction and exploration by decision-makers. During model development and analysis, we conduct rigorous sensitivity analysis to ensure the robustness of our findings. This included making structural adjustments based on team deliberations and assessing the resulting changes, as well as systematically varying model parameters.

Results

Model calibration & external validation

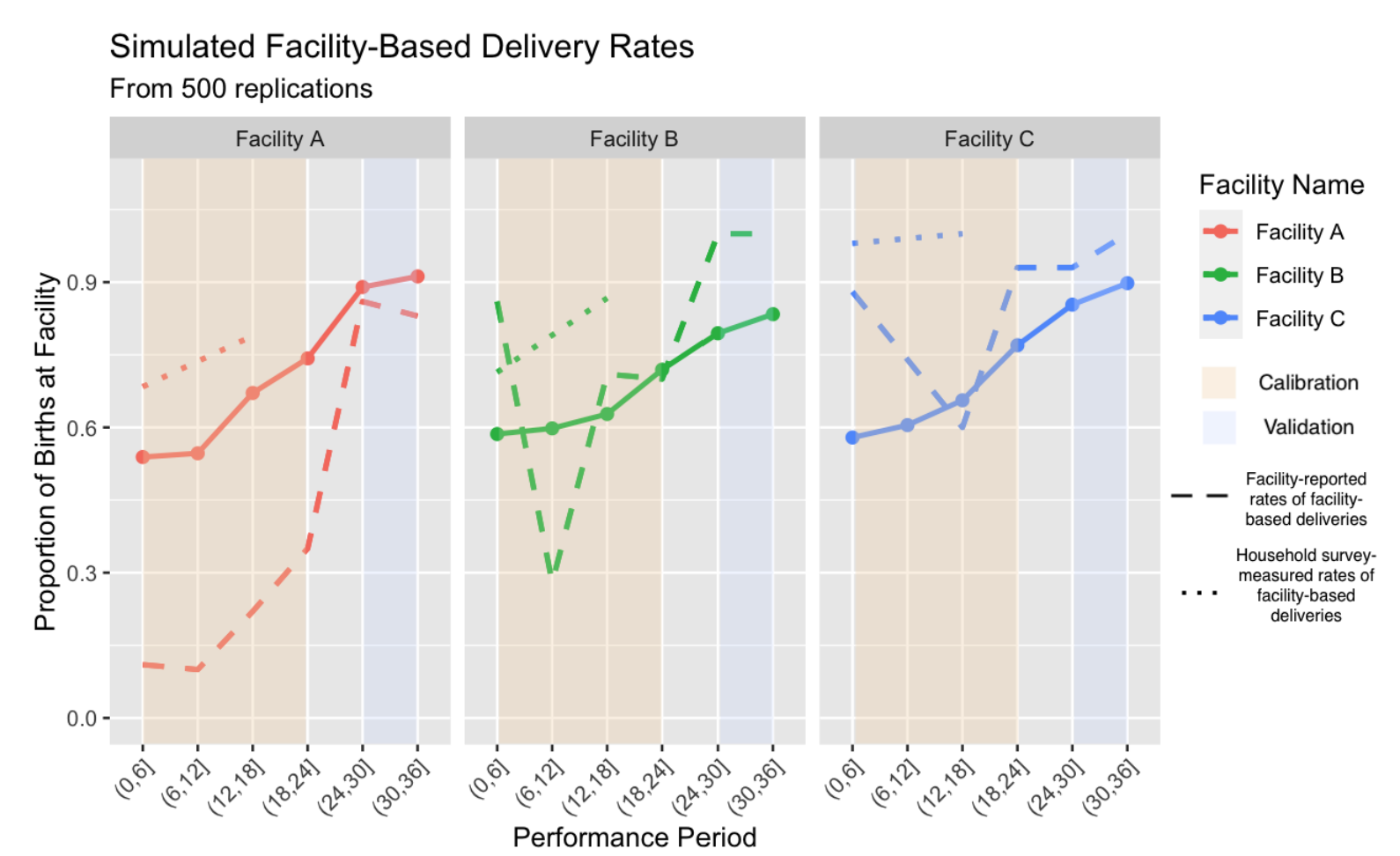

The simulated trajectories produced using the values of the best-fit calibration parameters were relatively well aligned with the rates of facility deliveries as shown in Figure 6. The combinations of parameters associated with the three lowest MSEs are shown in Table 9.

Consistent with the guidance of Nassar & Frank (2016), we focus on overall pattern matching rather than point-wise perfection since the empirical record is imperfect. Facility A records the largest root-mean-square error. This is primarily because empirical series combines two discordant sources: facility reported outcomes (which rise steeply from 13% to over 90%) and household-survey recall (which suggests a flatter trajectory). Reconciling those signals forces the calibration to compromise, leaving a wider gap for that facility while still minimising the pooled error across all sites.

The acceptability of a trajectory discrepancy should be judged in the light of data quality, modelling purpose, and stakeholder needs (Navarro 2019; Robinson et al. 2007). Survey snapshots may miss temporal variability, facility reported data can be incomplete, and both sources may be difficult to verify in low-resource settings. Following the quantitative-fit guidance and recent health-ABM validation supporting practices, we regard relative errors below 10–15% at endline as acceptable for policy-exploratory models (Collins et al. 2024). Using optimized calibration parameter values, the minimum mean squared error (MSE) between observed and simulated in-facility births, summed across the three facilities, was 1.52. For external validation, the difference between model-generated and facility-reported coverage for the last simulation period (months 30 to 36) was 7.7 percentage points (reported: 94.4%, simulated: 87.1%), well within the predetermined error bound limits. At endline, the model underestimated the coverage of two of the three facilities, as shown in Figure 6, which compares the performance of the observed and simulated facilities during the simulation period.

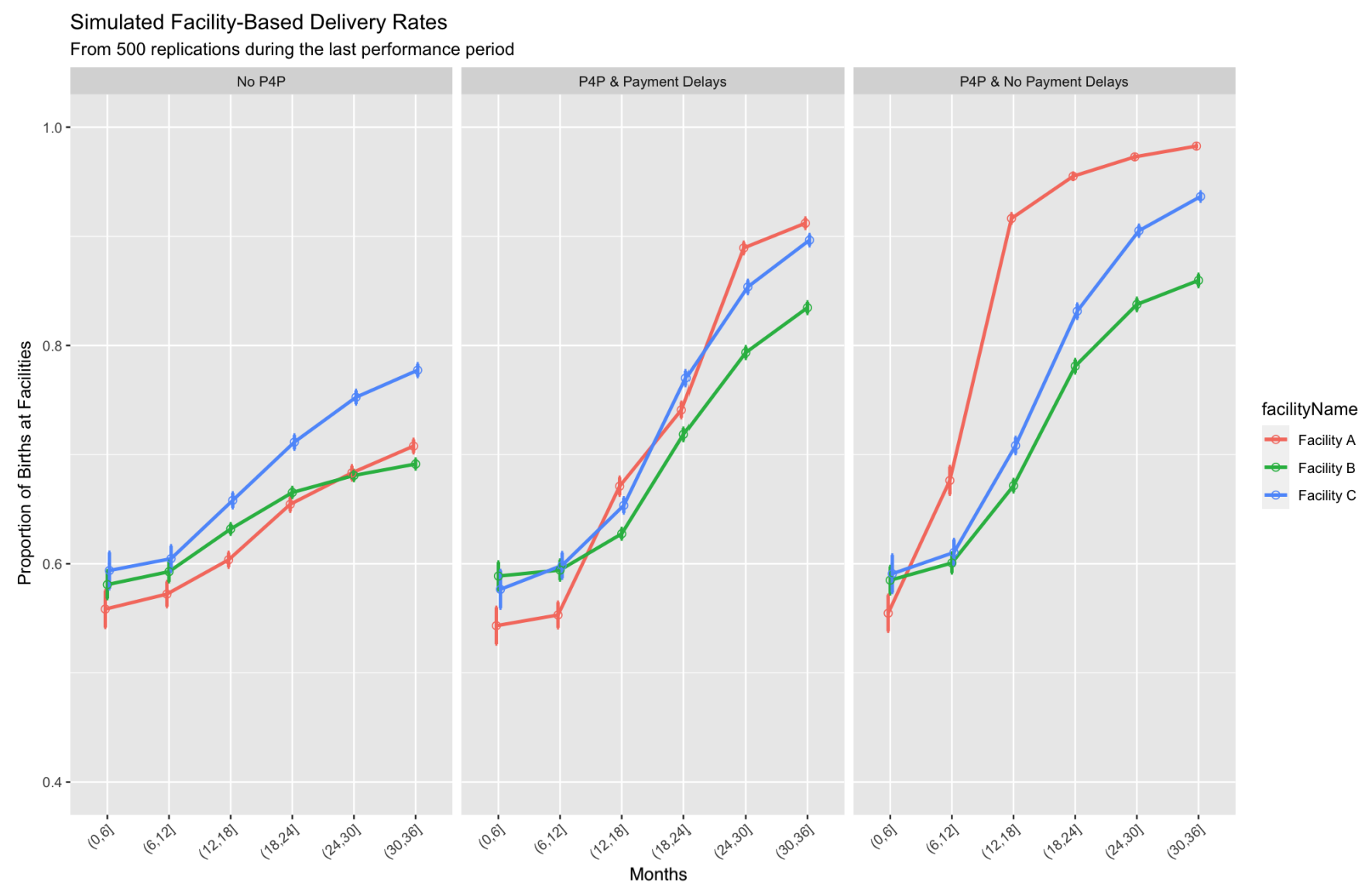

Scenario results

The model estimates that the current implementation of P4P (including DM visits and payment delays) produced a substantial increase in facility-based deliveries compared to the no P4P counterfactual. Specifically, the average facility-based delivery rate rose 15.4 percentage points (95% CI of difference [14.1, 16.7], and a relative increase of 21.5% (95% CI: [19.7%, 23.3%]) over the no P4P baseline (\(p<0.001\)) (see Table 6 for detailed statistics).

Our simulations indicate that eliminating bonus payment delays would have produced an additional absolute 4.1 percentage point increase in facility-based delivery rates (\(p<0.001\)) on top of the gains already achieved with the current P4P implementation. This represents a 4.7% relative increase compared to P4P with delays, and a 27.2% relative increase compared to the no P4P scenario (see Table 6).

DM visits showed measurable, though not statistically significant, benefits within the current P4P implementation that includes payment delays (\(p=0.55\)). However, these benefits were not observed in scenarios where payment delays were eliminated, as the DM’s role in facilitating drug sharing between facilities becomes less relevant. The slight, insignificant decrease associated with DM involvement in the absence of delays may be attributable to random variation.

The results are summarized in Table 5, which shows the coverage of institutional births combined for all three facilities under the three main simulated scenarios (No P4P, P4P with delays, P4P without delays). Consistent with the demand pathways in Sec. 3.6, our one–way sensitivity analysis (Table 13) identifies the home-experience modifier and the traditional birth attendant modifier as the largest contributors to endline coverage; these parameters map respectively to perceived quality/experience, outreach, and peer diffusion, and influence the observed +15.4 percentage-point increase under P4P.

Facility-based delivery rates

We explored individual facility-level performance trajectories in the three scenarios and found variations in the magnitude of effects between facilities.

Facility A, which has the lowest baseline performance, observed the highest increase in the proportion of institutional deliveries compared to the other two facilities under P4P scenarios, shown in Figure 7, though under the no P4P scenario it showed the second-highest increase. Specifically, the model estimates that facility-based deliveries for facility A under the current implementation of P4P with delays are 20.4 percentage points higher relative to the counterfactual where there is no P4P (70.8%, 95% CI = [70.2%, 71.4%] in no P4P vs 91.2% in P4P with payment delays, 95% CI = [90.7%, 91.7%])(Table 6). If P4P payments were made on time, the model estimates that facility A would achieve a facility-based delivery rate of 98.3% (95% CI = [98.1%, 98.4%], a 27.5 percentage point improvement over the counterfactual without P4P), as shown in Table 6.

Facility B, which has the largest catchment population and the lowest number of beds per capita, experienced smaller improvements in the rate of facility-based deliveries from P4P. The model estimates that the rate of facility-based deliveries for facility B under the current implementation of P4P with delays is 14.4 percentage points higher compared to the counterfactual where there is no P4P (69.1%, 95% CI = [68.7%, 69.6%] in no P4P vs. 83.5%, 95% CI = [82.9%, 84.0%] in P4P with delays). If P4P payments were made on time, the model estimates that facility B would achieve a facility-based delivery rate of 86.0%, 95% CI = [85.4%, 86.5%], a 16.9 percentage point improvement over the absence of P4P. In summary, facility B experienced modest benefits from P4P and on-time bonus payments, possibly due to its larger catchment population and high baseline performance.

Facility C experienced the smallest increase in the rate of facility-based deliveries from P4P. Specifically, the model estimates that the rate of facility deliveries for facility C under the current implementation of P4P with delays is 11.9 percentage points higher than the counterfactual where there is no P4P (77.7%, 95% CI = [77.1%, 78.3%] in no P4P vs. 89.6% in P4P with delays, 95% CI = [89.1%, 90.1%]). If P4P payments were made on time, the model estimates that facility C would achieve a facility-based delivery rate of 93.6%, 95% CI = [93.2%, 94.1%], a 15.9 percentage point improvement over the absence of P4P. In summary, facility C experienced the least benefits in performance from P4P and on-time bonus payments, but maintained its baseline high level of facility-based delivery.

| Experiment Setting | DM Visits | Rate (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | No | 65.7% | [63.8%, 67.6%] |

| No P4P | No | 71.8% | [71.5%, 72.1%] |

| P4P & Payment Delays | No | 86.3% | [85.7%, 86.9%] |

| Yes | 87.2% | [86.7%, 87.8%] | |

| P4P & No Payment Delays | No | 91.5% | [90.9%, 92.1%] |

| Yes | 91.4% | [90.8%, 92.0%] | |

| Facility | Facility Characteristics | Simulated Rates of Facility-Based Deliveries | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static | Dynamic (At Baseline) | No P4P (1) | P4P with Delays (2) | P4P without Delays (3) | |||

| Endline | Endline | \(\Delta_{(2)-(1)}\) | Endline | \(\Delta_{(3)-(1)}\) | |||

| Average | -- | -- | 71.7% | 87.1% | +15.4% | 91.2% | +19.5% |

| 95% CI | -- | -- | [71.4%, 72.0%] | [86.1%, 88.1%] | -- | [90.5%, 91.7%] | -- |

| A | Longest wait times, Shortest travel time | Least drug availability, No outreach, Highest Interpersonal Quality, Lowest performance | 70.8% | 91.2% | +28.9% | 98.3% | +38.8% |

| 95% CI | -- | -- | [70.2%, 71.4%] | [90.7%, 91.7%] | -- | [98.1%, 98.5%] | -- |

| B | Largest population, lowest bed capacity, Average staff number | - | 69.1% | 83.5% | +20.7% | 86.0% | +24.3% |

| 95% CI | -- | -- | [68.6%, 69.6%] | [83.0%, 84.0%] | -- | [85.5%, 86.5%] | -- |

| C | Shortest waiting times, Longest travel time | Highest staff kindness score | 77.7% | 89.6% | +15.3% | 93.6% | +20.4% |

| 95% CI | -- | -- | [77.1%, 78.3%] | [89.1%, 90.1%] | -- | [93.2%, 94.0%] | -- |

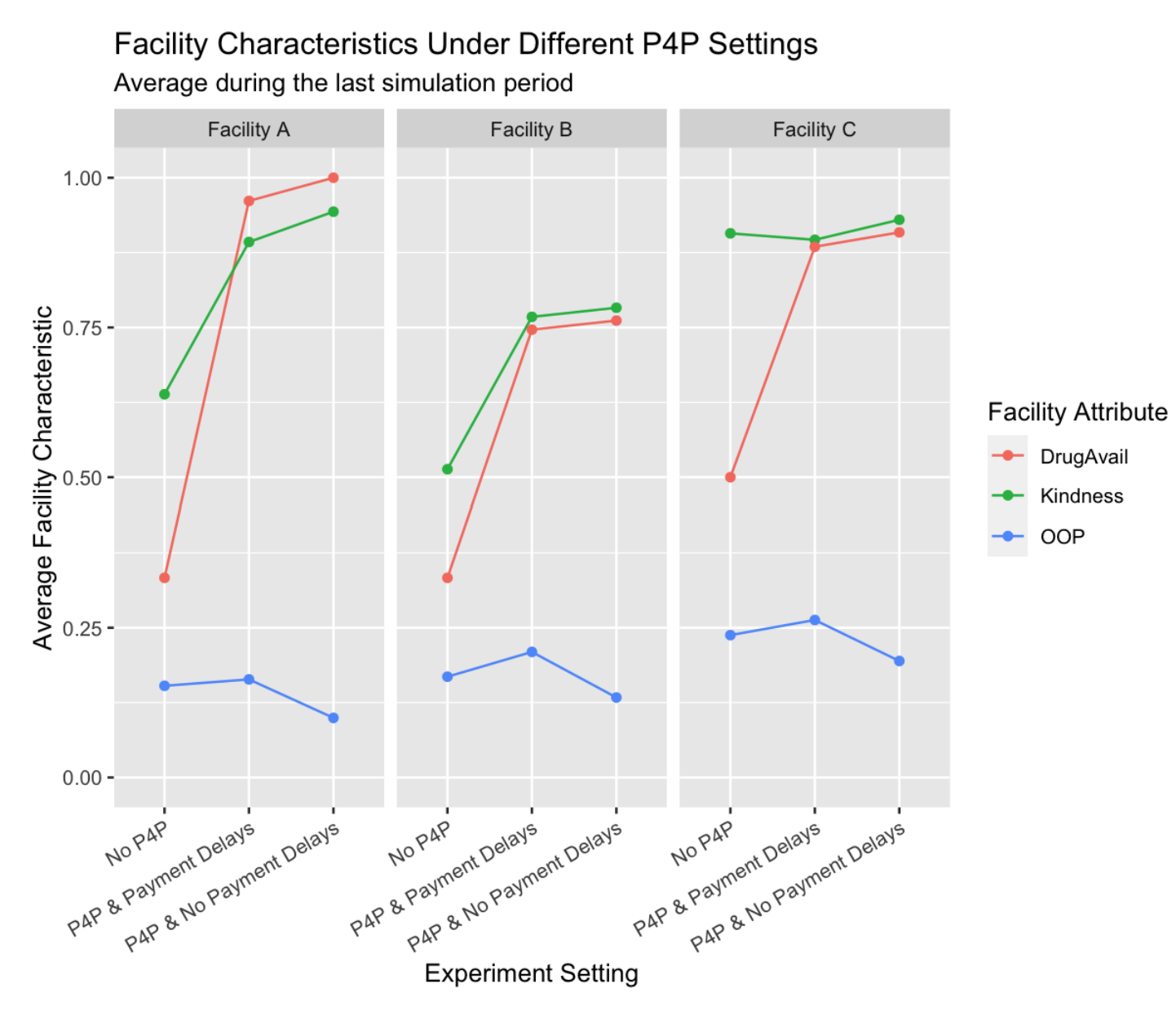

Facility characteristics

The three main scenarios (No P4P, P4P with payment delays, and P4P without payment delays) resulted in notable changes in dynamic facility characteristics: drug availability, staff kindness, and out-of-pocket payments. For traceability, we focus on changes in these particular facility characteristics that encompass multiple aspects of patient care. Specifically, drug availability is related to access in terms of medication, staff kindness is related to patient experiences during care provision, and out-of-pocket payments represent financial access barriers.

The implementation of P4P, even with payment delays, led to substantial improvements in drug availability. The model estimates that the current implementation of P4P produced a 47.5 percentage point increase in drug availability compared to the counterfactual without P4P (Drug Availability in No P4P: 38.9%, Drug Availability in P4P with delays: 86.4%). Removing payment delays in the P4P scenario led to a further 2.6 percentage point increase in drug availability (Drug Availability in P4P with no delays: 89.0%).

Staff kindness also increased under P4P conditions, with the current implementation associated with a 16.6 percentage point increase over the no P4P scenario (Kindness in No P4P: 68.6%, Kindness in P4P with delays: 85.2%). This rate improved by 3.3 percentage point with the removal of payment delays (Kindness in P4P with no delays: 88.5%).

Out-of-pocket (OOP) payments showed a somewhat different trend, increasing slightly by \(14.0\%\) (relatively) with the introduction of P4P with delays (OOP in No P4P: 18.6%, OOP in P4P with delays: 21.2%), but decreasing by \(32.9\%\) (relatively) when payment delays were removed (OOP in P4P without delays: 14.3%).

Facility-Level Characteristics. All facilities observed notable changes modifiable characteristics as shown in Figure 8. Drug availability significantly increased with the implementation of P4P, with Facility A making the largest leap from 33.3% to a full 100.0% in the no-delay scenario. Despite the initial increase, all facilities also benefitted from eliminating payment delays, which signifies the positive impact of timely bonus payments on drug availability.

In terms of staff kindness, Facility C maintained a noticeably high baseline, therefore showing the least improvement, albeit a positive increase to 93.0% without payment delays. Meanwhile, Facilities A and B exhibited substantial improvements, highlighting the substantial boost in staff motivation that P4P can bring, further amplified by eliminating payment delays.

For out-of-pocket payments, the initial implementation of P4P with delays led to a surge across all facilities. However, eliminating these delays turned the tide, resulting in significant reductions in out-of-pocket expenses, most notably in Facility A, which fell to 10.0%, demonstrating the significant potential to reduce patient expenses by removing payment delays.

In general, removing payment delays within the P4P framework seems to foster not only improved drug availability but also enhanced staff kindness and lower out-of-pocket expenditures, presenting a more patient-friendly environment across all facilities.

Cross validation

To provide a holistic perspective on P4P implementation effects, we compared our ABM results with findings from (1) complementary modeling approach by our research team and (2) Pwani P4P evaluation experiment (Borghi et al. 2013, 2021). The system dynamics model by Cassidy et al. (2025) modeled a single representative facility using data from 75 evaluation facilities, district-level data, and national statistics. In contrast, our ABM explicitly modeled three specific public facilities (representing around 4% of the 75 facilities in the Pwani evaluation study; Borghi et al. (2021)).

Despite the different modeling approaches and scopes, both models agree on key mechanisms: drug availability serves as the primary demand trigger, and payment delays erode supply-side gains. However, they capture different aspects of the system - the SDM focuses on severe payment delays while our ABM also captures the associated rise in out-of-pocket fees (a variable not represented in the SDM). The SDM treats low baseline drug stocks as a hard ceiling, whereas the ABM shows greater catch-up potential in such settings through its agent-level decision-making framework.

Our ABM’s counterfactual (no-P4P) scenario projects 71.7% facility-based delivery coverage at endline, compared to 89.4% observed in the 75 control facilities in the Pwani evaluation (Borghi et al. 2021). For the P4P-with-delays scenario, our ABM estimates 87.1% coverage, closely aligning with the SDM’s intervention estimate of approximately 89.7% (Cassidy et al. 2025). The lower counterfactual projection in our ABM likely reflects the specific characteristics of the three modeled facilities rather than the broader distribution of all evaluation facilities.

This triangulation across different modeling approaches and program evaluation, each with distinct abstractions and design decisions, strengthens our understanding of P4P dynamics. Like ensemble modeling in climate science or epidemiology, examining these complementary perspectives provides a more comprehensive picture of how payment delays and facility characteristics influence maternal healthcare seeking behavior, even when exact numerical predictions differ.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analyses demonstrate that our model’s general observed patterns and conclusions may vary slightly with key input variables. Specifically, we run a sensitivity analysis on the key input parameters as well as structural sensitivity analysis to uncover the model’s dependence on key structural assunmptions.

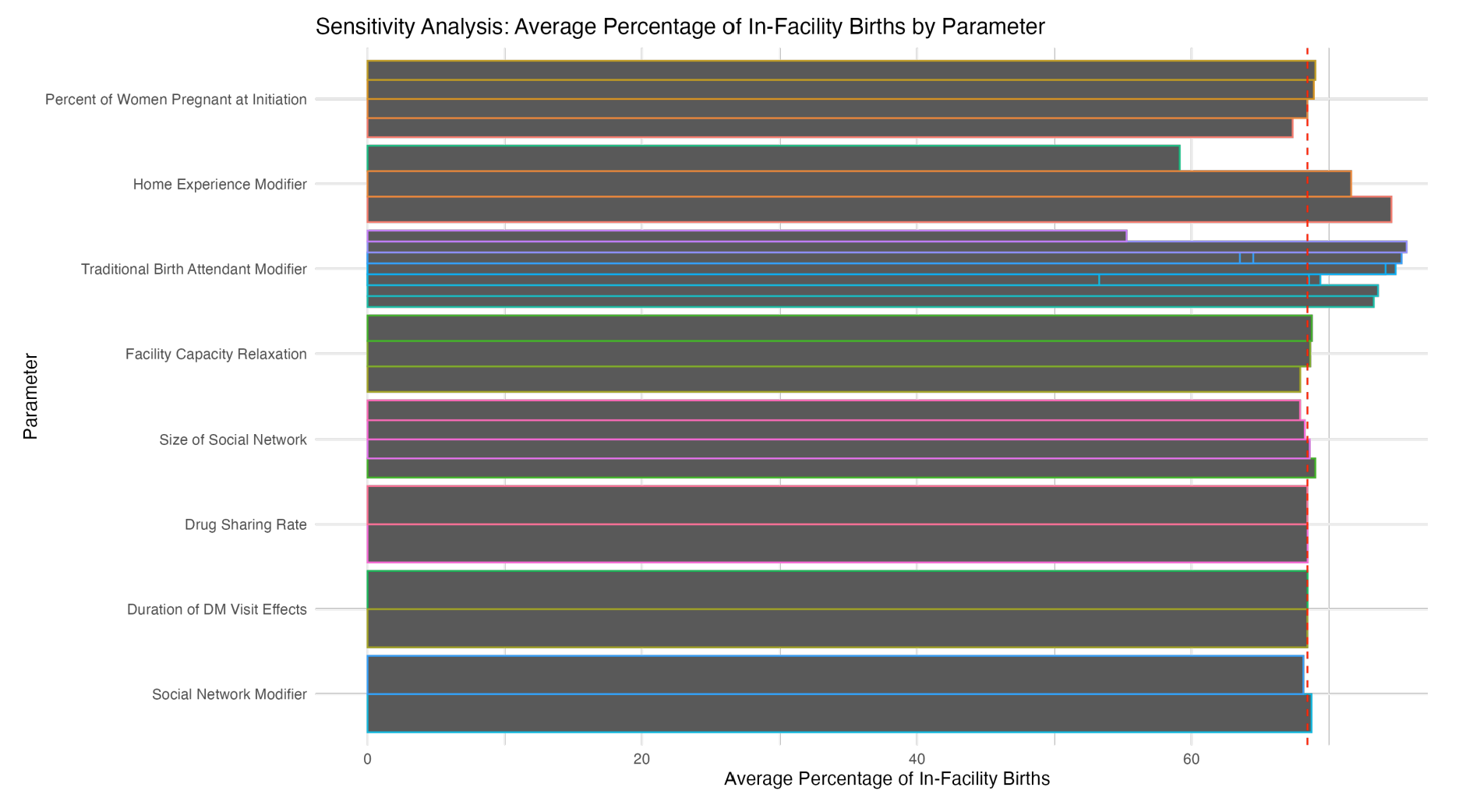

The sensitivity analysis of input parameters revealed varying degrees of influence on the percentage of in-facility births. We varied key model inputs using a scale adapted from Semwanga et al. (2016), which categorizes sensitivity based on the percentage change in model output. Importantly, the relative performance of the facilities remained consistent under these changes for most of the input parameters. The few exceptions were the Traditional Birth Attendant Modifier (\(M_{\textit{TBA}}\), range: 0.25–0.4), which exhibited the most substantial impact with a 42.1% change in the average percentage of in-facility deliveries across its range, closely followed by the Home Experience Modifier (\(M_{\textit{hExp}}\), range: 0–0.05) at 26.1%. Conversely, parameters such as the Drug Sharing Rate (DrugSharRate, range: 5–10%) and Duration of District Manager Visit Effects (DM \(\textit{VisitDuration}\), range: 0.5–1) showed minimal influence, with percent changes of 0.031% and 0.023% respectively. The Facility Capacity Relaxation (Beds, range: 1–3), while not among the most sensitive parameters, still demonstrated a notable effect with a 1.244% change. Other parameters, including the Occupancy Adjustment (OccAdjustor), Percent of Women Pregnant at Initiation (\(p_{\textit{PregnantInitiation}}\)), Facility Experience Modifier (\(M_{\textit{fExp}}\)), Social Network Modifier (\(M_{\textit{social}}\)), Drug Sharing Threshold (DrugSharThres), and Size of Social Network (\(n_{social}\)), showed less degrees of sensitivity. Appendix H provides detailed results of the sensitivity analysis performed on the calibrated simulation model.

These results highlight the importance of focusing on community-level interventions and women’s prior experiences when designing strategies to increase facility-based deliveries, while suggesting that aspects like drug sharing and the duration of managerial visits may have less immediate impact on this particular outcome. Given the significant influence of certain parameters, particularly those related to community factors, it is important to prioritize the accurate quantification of these input parameters to enhance the model’s predictive power and reliability.

An example of the structural changes made during the model development process involved the bonus effects mechanism. Specifically, we incorporate a dependence of the bonus effects on both the current bonus and the bonus from the previous period. Additionally, we modified the model so that the staff’s motivational response would coincide with the receipt of the bonus, as opposed to occurring at the end of the performance period. Despite these alterations, we observed that the changes in facility performance were not substantial.

Discussion

This paper describes the formulation, parameterization, and validation of an ABM to explore the effects of a P4P program on the delivery care and facility characteristics in a primary care setting. The model also explores the effect of incentive payment delays on outcomes and the heterogeneity of effects across facilities. We demonstrate the feasibility of building an ABM as an ex-post evaluation tool to further unpack program effects, with the model subjected to validity testing. To our knowledge, this is the first ABM to evaluate the effect of a health system strengthening program such as P4P in a low or middle-income setting.

Methodological contribution